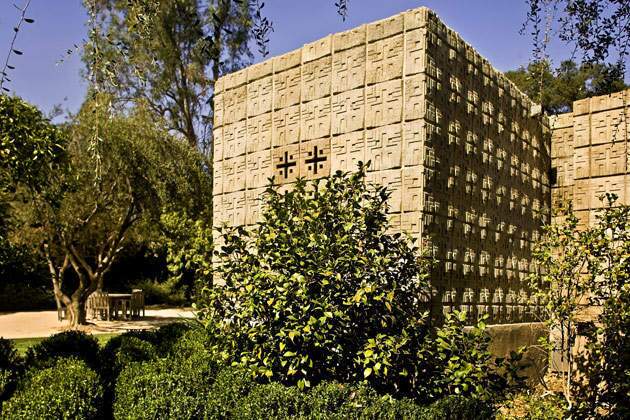

Landmark houses: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Millard House (La Miniatura)

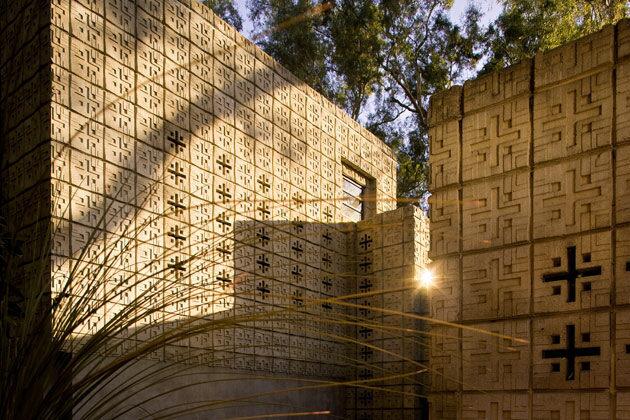

The Alice Millard house was Frank Lloyd Wright’s first “textile-block” house, the term for the architect’s way of stacking decorative concrete blocks that were knitted together like fabric. In the three textile-block houses that followed Millard’s, Wright used steel threads of rebar, which, before the invention of epoxy coating, rusted and degraded the concrete. The lack of rebar in the Millard house has been a blessing, as the blocks have fared better since construction in 1923. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

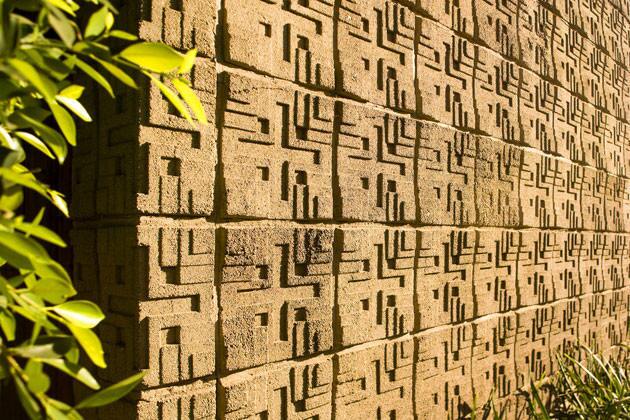

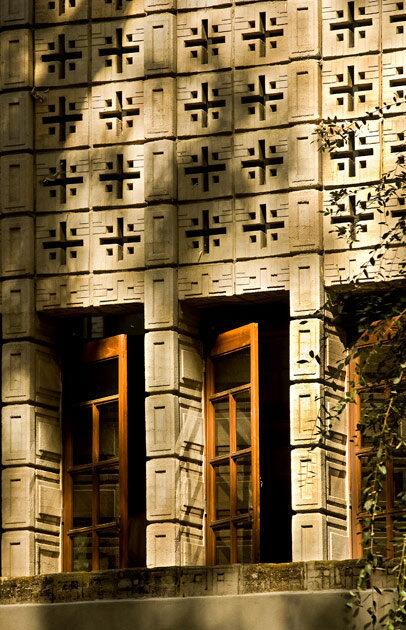

Wright saw himself as “the weaver,” knitting together concrete blocks made locally from wooden molds. Each block was 16 inches square and scored in a cruciform pattern suggestive of primitive American Indian design. But because the wood expanded and contracted, the results did not turn out to be as uniform as was expected, and the architect sparred with the contractor. Wright complained, “We had no skilled labor, and the builder’s relatives set the blocks.” (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

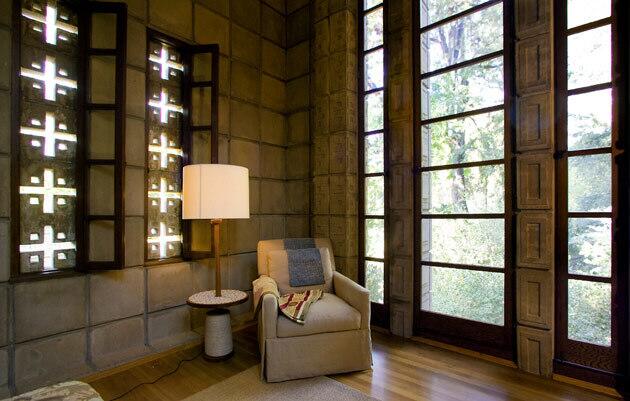

That classic Frank Lloyd Wright move -- the low ceiling -- leads from the entry to the airy living room. A blending of traditions can be seen in the way the concrete blocks are juxtaposed with the finely detailed redwood ceiling, doors and windows. Wright arranged the perforations in the blocks to create a concrete shell that feels lighter than it actually is. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The view of the room from the other side of those glass doors. The blocks above the doors have panes of glass sandwiched in the middle of the patterned concrete, so dappled light passes through in ever-shifting patterns and intensities. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

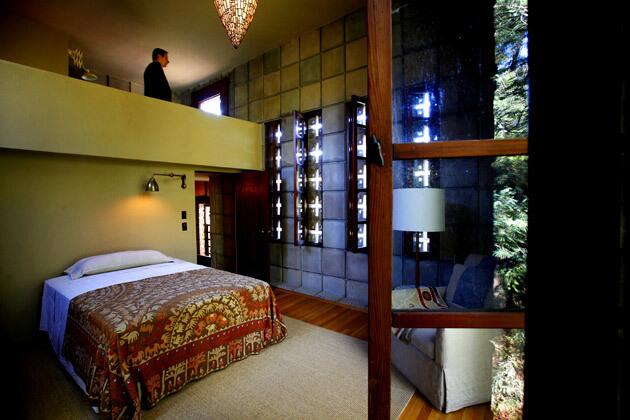

The client, Alice Millard, indulged Wright’s affinity for Mayan inspired architecture but got her desire for old-world European elegance in the form of the ornate fireplace screen. Stairs lead to a narrow landing above the fireplace that looks down on ... (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

... the living room’s play of light and shadow. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The low, intricately detailed ceiling tops the room in the warmth of redwood. The landing leads to ... (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

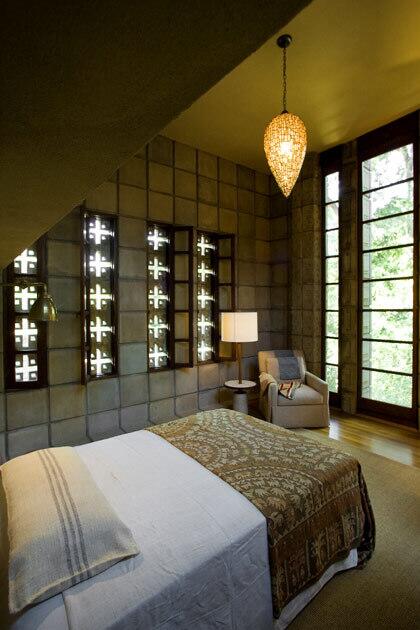

... the petite master bedroom. The concrete blocks create a sense of protection and seclusion, while the high ceiling prevents the room’s modest footprint from triggering claustrophobia. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Treetops peek through the master’s glass door and windows. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The master bedroom closet is behind the bed; the high ceiling allows for a balcony above. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Alice Millard chose the doors, including this one to the main bathroom, where she also insisted on Delft tile atop the vanity. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

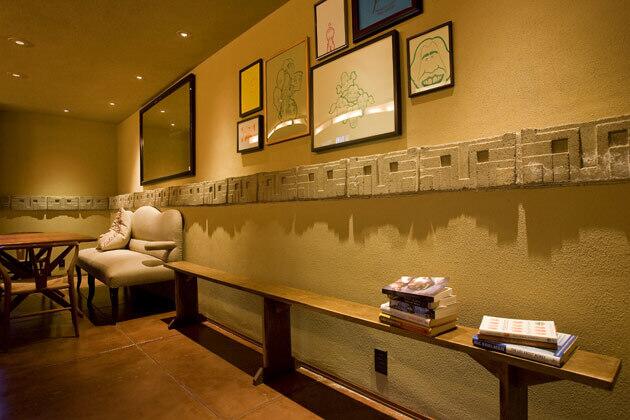

A path leads from the main house around the pond and to a guest studio designed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, Lloyd Wright, who was the construction supervisor on the main house. Millard wanted a place to display her antiques, and Lloyd Wright included a kitchen, dining area, mezzanine bedroom and bathroom. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Like the main house, the studio has been updated. The property as a whole comes to 4,200 square feet of living space, including four bedrooms and four bathrooms. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

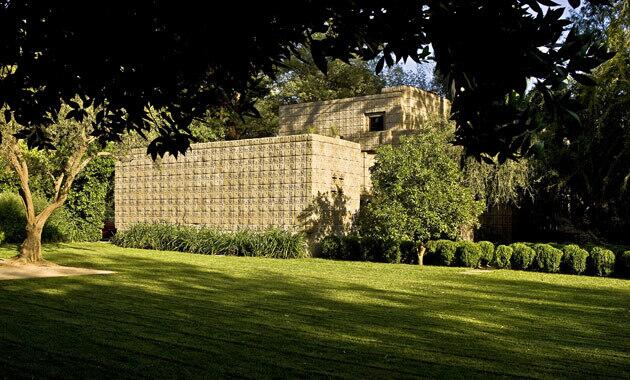

Grounds include a large lawn set to the side of the house. When Wright was working on the blueprint, he explained that he was after what he found missing from other local homes: “A distinctly genuine expression of California in terms of modern industry and American life.” (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Another view of the exterior and, off in the distance, a table and chairs set under an olive tree. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The Millard house is owned by television commercial producer and architecture buff David Zander, who is credited for making important restorative improvements to the property. He has placed the Millard house for sale, recently listed at $4,995,000. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A detail of the garage door. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

By Sean Mitchell

Frank Lloyd Wright’s alluring Alice Millard house, also known as La Miniatura, rises like a Mayan temple from a tree-canopied hillside on Rosemont Avenue in Pasadena. The 1923 Millard house may be less known to the general public than Wright’s other three “textile-block” homes in the region -- Ennis, Freeman and Storer -- but some architectural historians regard Millard as the finest. So does Eric Lloyd Wright, the architect’s grandson and a longtime Southern California architect who explained the leading reason for critics’ enthusiasm: “The way he set the house in that glen,” he said. Frank Lloyd Wright called for the house to rise above a ravine between two eucalyptus trees, which are still there, forming a cathedral more than 100 feet high over a lily pond. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)