- Share via

Worldwide criticism of fast fashion’s waste, labor abuses and carbon emissions has done little to slow down the industry. But new legislation could alter the flood of goods — like the floral print jumpers priced at, say, $2.99, the kids’ T-shirts selling for $4.26 or the tank tops for $4.88.

The term “fast fashion” — which emerged in the 1990s alongside Zara, a European company selling runway-inspired styles at affordable prices — has come to define trendy, low-cost clothing to wear and throw away.

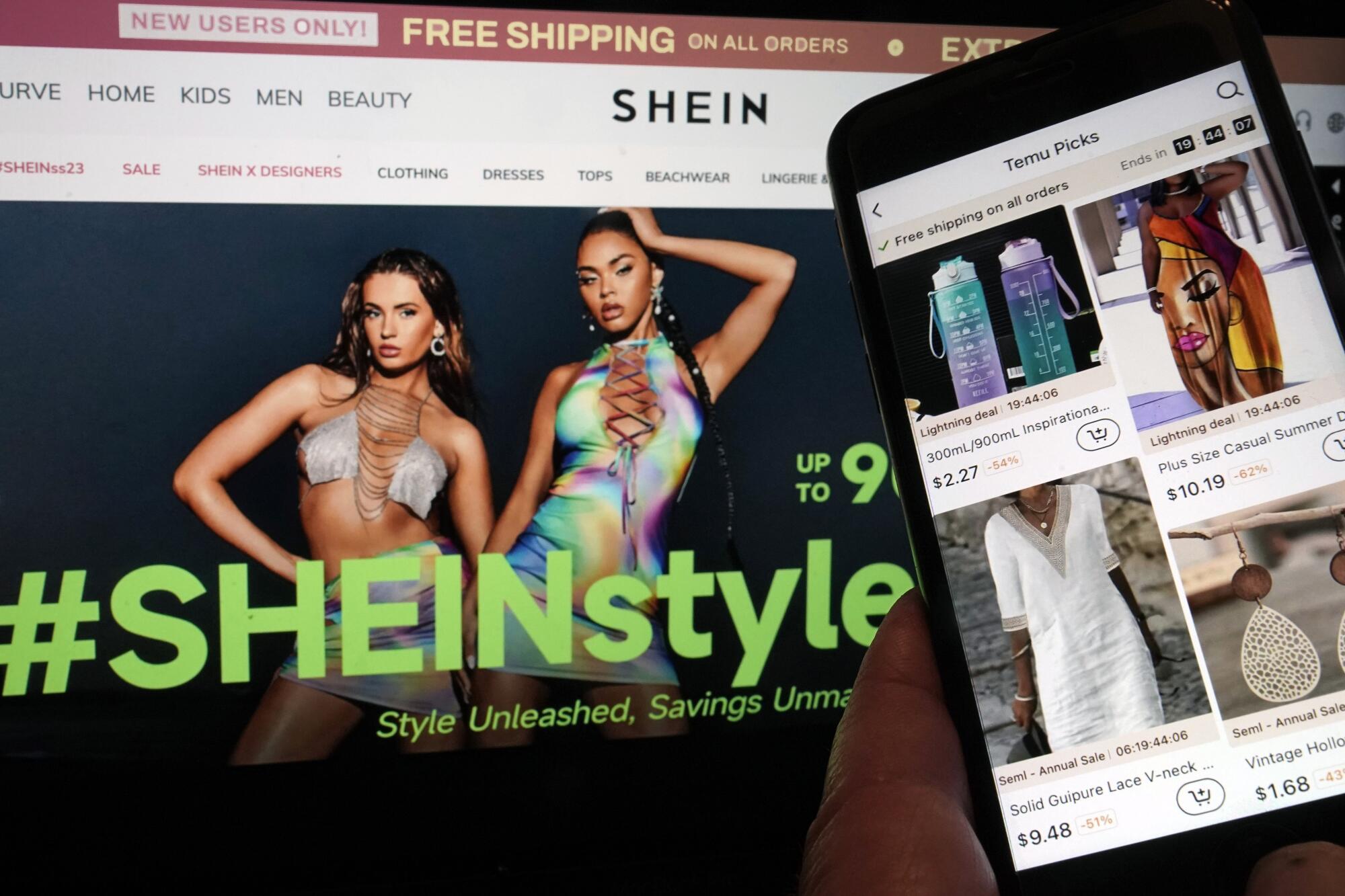

The business model has been popular among shoppers and brands, which keep their inventories low, try to predict what customers want and use highly-flexible supply chains for quick turnaround. The latest iterations are epitomized by the wildly successful Chinese e-commerce platforms Shein and Temu.

A traditional retailer may offer 1,000 different styles per year, said Sheng Lu, professor and graduate director of fashion and apparel studies at the University of Delaware. Compare that to the first generation of fast-fashion brands, Zara and H&M, which put out about 20,000 per year. Shein, he added, which has garnered the label of “ultra-fast fashion,” churns out 1.5 million different styles per year.

According to consulting firm McKinsey & Co., which estimates the global fashion industry to be worth $1.7 trillion, clothing production doubled between 2000 and 2014, and the number of garments purchased per capita increased by 60%. At the current pace, McKinsey predicts clothing and footwear consumption will increase from 62 million tons in 2019 to 102 million tons in 2030, “equivalent to more than 500 billion additional T-shirts,” according to the Clean Clothes Campaign.

As clothing prices have plummeted — a few months ago, McKinsey reported that the average price of a product on Shein is $14, $26 at H&M and $34 at Zara — customers have fewer qualms about tossing them. Less than 1% of fashion textiles are recycled, McKinsey reported, and 3 out of every 5 garments end up in a landfill or are incinerated per year.

But as fast fashion’s popularity rises, so has the backlash against it, drawing the ire of environmental groups, labor activists and lawmakers across Europe and the United States. “The discussion on fast fashion is quickly moving from the traditional business aspect to the policy aspect,” Lu said.

Recent legislation in several countries is aimed at curbing the environmental impact of the fashion industry, whose planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions are estimated to exceed those of international flights and maritime shipping combined. McKinsey estimates that the fashion industry accounts for between 3% and 8% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and could increase by another 30% by 2030.

France is leading the effort to push back against fast fashion. In March, the lower house of Parliament approved a bill that would ban advertising for such items and impose penalties per piece of clothing sold. France has proposed a European-Union-wide ban as well on used clothing exports to discourage discarding cheap goods that end up in landfills overseas.

New York lawmakers have crafted a bill that would require major fashion brands doing business in the state to map and disclose supply chains to avoid labor exploitation and environmental harm.

According to McKinsey’s 2024 State of Fashion report, 87% of fashion executives surveyed believe sustainability regulations will affect their business this year. “The game is changing,” Lu said. “These regulations and consumer changing behavior will really place some pressure on these fast-fashion brands.”

Shein, which uses predictive analytics to determine what clothing designs will sell best, has argued that its business model is less wasteful than traditional retailers’ because it produces only as much as customers order.

Still, those companies most associated with the phenomenon are trying to diversify their offerings to eschew the label of fast fashion and all its negative connotations.

With a new third-party marketplace, Shein customers can now find secondhand luxury goods on its site. Zara, the onetime fast-fashion pioneer, has pledged to transition to all sustainable, organic or recycled material by 2025, and incorporate offerings of higher quality and cost to its product lines.

But the influence of fast fashion isn’t going away — exemplified by the global garment supply chain, which has been altered as traditional retailers have adopted practices to increase their own speed and flexibility.

Before the advent of fast fashion, a standard piece of apparel took about two months to produce, according to Raymond Wong, a professor in the department of logistics and maritime studies at Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Now fast fashion can produce an item, from concept to delivery, in less than two weeks.

And as production capabilities have sped up, so have the life cycles of the clothing that retailers are selling. While clothing collections have traditionally been seasonal, fast-fashion brands can launch at least one new collection per month now, Wong said.

And being fast, brands have learned, pays off.

Profit margins at companies that embrace fast fashion are generally higher than traditional retailers, Wong said, because they prioritize sales volume and low-cost production. Keeping sparse inventory also means that they don’t have to offer steep discounts to offload unsold merchandise.

“This is the philosophy of the fast fashion retailer: If you can put your item in the store one day earlier, you have higher possibility and probability to sell more,” Wong said.

A more flexible production cycle means that brands are working with more vendors, manufacturers and suppliers than before. That makes assessing the supply chain for transgressions in labor and environmental standards more challenging.

Sanchita Saxena, a professor at UC Berkeley who studies labor and garment supply chains in Asia, said that while more brands are trying to improve sustainability, their cost expectations make it difficult for suppliers, many of which are taking losses on accepted orders, to take action.

The impact of fast fashion is “terrible for workers because the cycle is so quick and the turnaround time is so fast, there is no way a human being can produce the amount of goods that is required,” Saxena said. “But they’re getting incredible pressure to do that, and they’re always getting pushed on price.”

Despite concerns about the negative impacts of fast fashion and sustainability pledges, experts say consumers alone won’t have much influence in how the clothing supply chain adapts.

“The consumer is making statements that they want to purchase more ethically and responsibly, but they’re not really showing that in the scale that is necessary to make brands act,” said Divya Demato, chief executive of San Francisco-based supply chain consulting firm GoodOps.

Temu, a low-cost shopping app that gained popularity last year, was created by the Chinese e-commerce platform Pinduoduo to tap into that price sensitivity among U.S. consumers.

According to McKinsey, 40% of U.S. consumers have shopped at Shein or Temu in the last 12 months. Many survey respondents said they intended to buy more from those fast-fashion brands in the next two to three years.

“It becomes sort of a chicken-or-egg situation. Brands say ‘Consumers want it, so we give it to them,’ and consumers say, ‘Well, brands are doing this, so we are buying it,’” Saxena said. “Which came first? I don’t know — but someone needs to stop that cycle.”

Special correspondent Huiyee Chiew in Taipei, Taiwan, contributed to this report.