- Share via

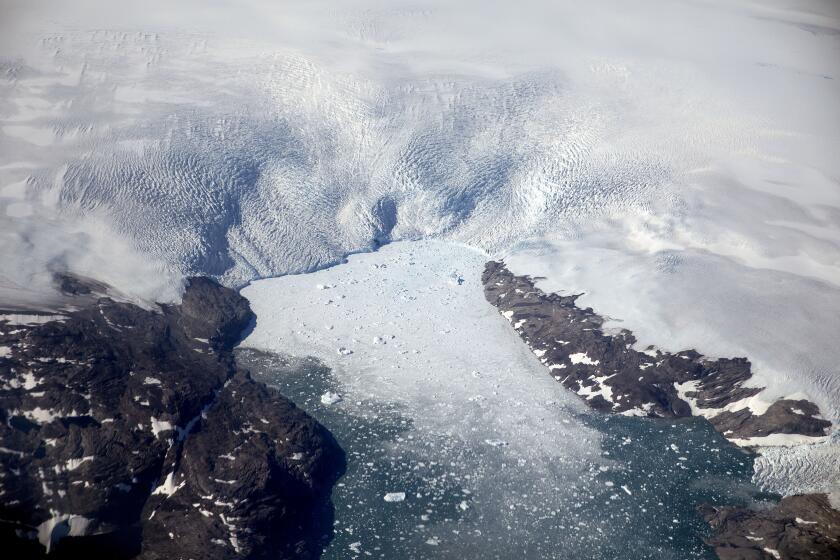

The loss of Arctic sea ice has long been a graphic measure of human-caused climate change, with wrenching images of suffering polar bears illustrating a worsening planetary crisis. Now, new research has found that Arctic Ocean sea ice is shrinking even faster than previously thought — and that the Arctic may start to see its first “ice-free” days within the current decade.

That troubling milestone could occur before the end of the decade or sometime in the 2030s — as many as 10 years earlier than previous projections, according to a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Reviews Earth and Environment. The study defines “ice-free” as when the Arctic Ocean has less than 1 million square kilometers, or 386,000 square miles, of ice.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

“It’s no longer a remote possibility that might happen at some point,” said Alexandra Jahn, the study’s lead author and an associate professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. “Unfortunately, it basically occurs under all the emission scenarios in our climate models, so it seems like it’s going to happen, and so we need to be ready for that.”

By midcentury — 2035 to 2067 — the Arctic could see consistent ice-free conditions in September, the month when sea ice concentrations are typically at their minimum, the study found.

The precise timing of such losses depends on how soon humanity is able to reduce fossil fuel emissions that are contributing to global warming. Under a high-emission scenario in which fossil fuel use continues unabated, the Arctic would be ice-free between the months of May and January by 2100, the study says.

Even under a low-emission scenario, the Arctic would still be ice-free between August and October by that same year.

Climate models dating to the 1970s have long predicted the possibility of reaching ice-free summer conditions in the Arctic under sufficient warming, but the latest research has helped nail down just how quickly it may happen, Jahn said.

The consequences of such a change are not yet fully understood, but considerable effects on ecological systems, wildlife and local and global climates are likely.

“The more emissions the world puts into the atmosphere, the more months we could see an ice-free Arctic,” Jahn said. She added that even in a reduced emissions scenario, “children born today will see ice-free conditions at least in September, and every couple of years in October and August.”

New research warns of a possible collapse in Atlantic Ocean currents due to climate change. That could fundamentally alter global weather patterns.

The study paints a vivid picture of a changing planet where the formerly “white Arctic” defined by its ice is transformed into a “blue Arctic” characterized by open water.

Yet the decline of Arctic sea ice has been well documented since at least 1979, when continuous satellite observations began. Since then, there has been a roughly 40% loss in surface area and a 50% loss in thickness, according to Walter Meier, a senior researcher with the National Snow and Ice Data Center, who was not involved with the study.

Meier said the study’s assessments are plausible, although the most urgent finding involving an ice-free day within the decade “may be a little aggressive.”

Still, he said, “given the emission scenarios that we’re following, it’s really a matter of when, not if, we’ll get ice-free conditions.”

Indeed, the study comes as the planet continues to experience unprecedented heating driven by climate change and this year’s El Niño, with January becoming the eighth month in a row to experience record warmth, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

February data were not yet available, although early findings point to continued heating, including the warmest meteorological winter in the United States.

The global surface temperature in January was 2.29 degrees above the 20th century average of 54 degrees, NOAA found. Global sea ice extent was the seventh-smallest in the 46-year record at 6.90 million square miles, or 440,000 square miles below the 1991-2020 average, for the winter month.

Jahn said some research has found there is still a 10% to 20% possibility of avoiding an ice-free Arctic altogether if the global temperature stays below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming on a 20- to 30-year mean. The 1.5-degree benchmark is an internationally agree-upon threshold for reducing the worst effects of climate change.

“If we were to stop all emissions tomorrow — which physically isn’t possible, but if we could — then we could still avoid it,” Jahn said. “It’s not a guarantee, but there’s a possibility.”

But even that possibility appears to be slipping away. In January, the global average temperature measured 1.66 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial reference period, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Every bit of planetary warming will have impacts beyond those already occurring, including biodiversity loss, longer heat waves and extreme rainfall.

The implications of an ice-free Arctic Ocean — which spans an area roughly equivalent to the size of the lower 48 United States — are worrisome. According to the study, the loss of sea ice would contribute to increased wave heights, and greater coastal erosion in the region, among other things. It would also threaten the survival of ice-dependent animals such as polar bears and seals, and trigger the migration of some fish and other species.

“There’s going to be a big shift in what kind of species we see where, and which ones end up being the dominant ones and surviving,” Jahn said. The outlook for polar bears is especially grim because they primarily hunt on sea ice, and “if there is an open-ocean season for several months of the year, then polar bears just can’t survive anymore.”

For better or worse, the loss would also increase economic activity in the Arctic by opening up more shipping routes and areas for resource exploration, the study says.

Other potential outcomes include reductions in albedo — or the amount of light reflected by the ice — which would accelerate human-caused warming by creating an amplifying feedback loop. More controversial research argues that a decrease in Arctic sea ice could affect the jet stream and its associated weather patterns, and even lead to more favorable fire conditions in the western U.S.

Many changes are already underway, said Meier of the NSIDC.

“It’s not like flipping a switch where it’s one type of Arctic Ocean environment, and then it’s ice-free and suddenly it’s something else,” he said. “We’ve already seen a lot of changes in the Arctic Ocean and the region around it.”

From California to New England to Europe, many areas of the Northern Hemisphere are approaching a ‘snow-loss cliff’ due to global warming, researchers say.

It also would not be the first time the Arctic has been ice-free, geologically speaking. Evidence shows the Arctic was ice-free between 80,000 and 150,000 years ago, and possibly after the last Ice Age 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

“If we’re not in uncharted territory, we’re getting toward uncharted territory — and we’re certainly in uncharted territory in the history of human civilization,” Meier said. “We’re seeing something that is quite extraordinary and is a really important climate signal, and pretty iconic.”

The good news is that the potential loss of Arctic sea ice is not irreversible, Jahn said. Sea ice comes back every winter and may be able to revert to its previous conditions in as quickly as seven years. That’s a key difference between sea ice and ice on land, such as glaciers or ice sheets in Greenland, which take thousands of years to grow.

Still, the very likely possibility of an ice-free Arctic within the coming decades is an important reminder that humanity should strive to reduce emissions and keep warming below the limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius, she said.

“While everybody can reduce their individual carbon footprint — and that can have positive impacts — we really need the big policy decisions to reduce emissions globally to make an impact,” Jahn said.

How quickly those decisions are made and implemented can mean the difference between limited future losses, or five or more months of guaranteed ice-free conditions, she added.

“These are really completely different potential Arctics that we’re looking at by the end of the century,” she said. “And it’s really in our hands to try and go for the least bad option.”