- Share via

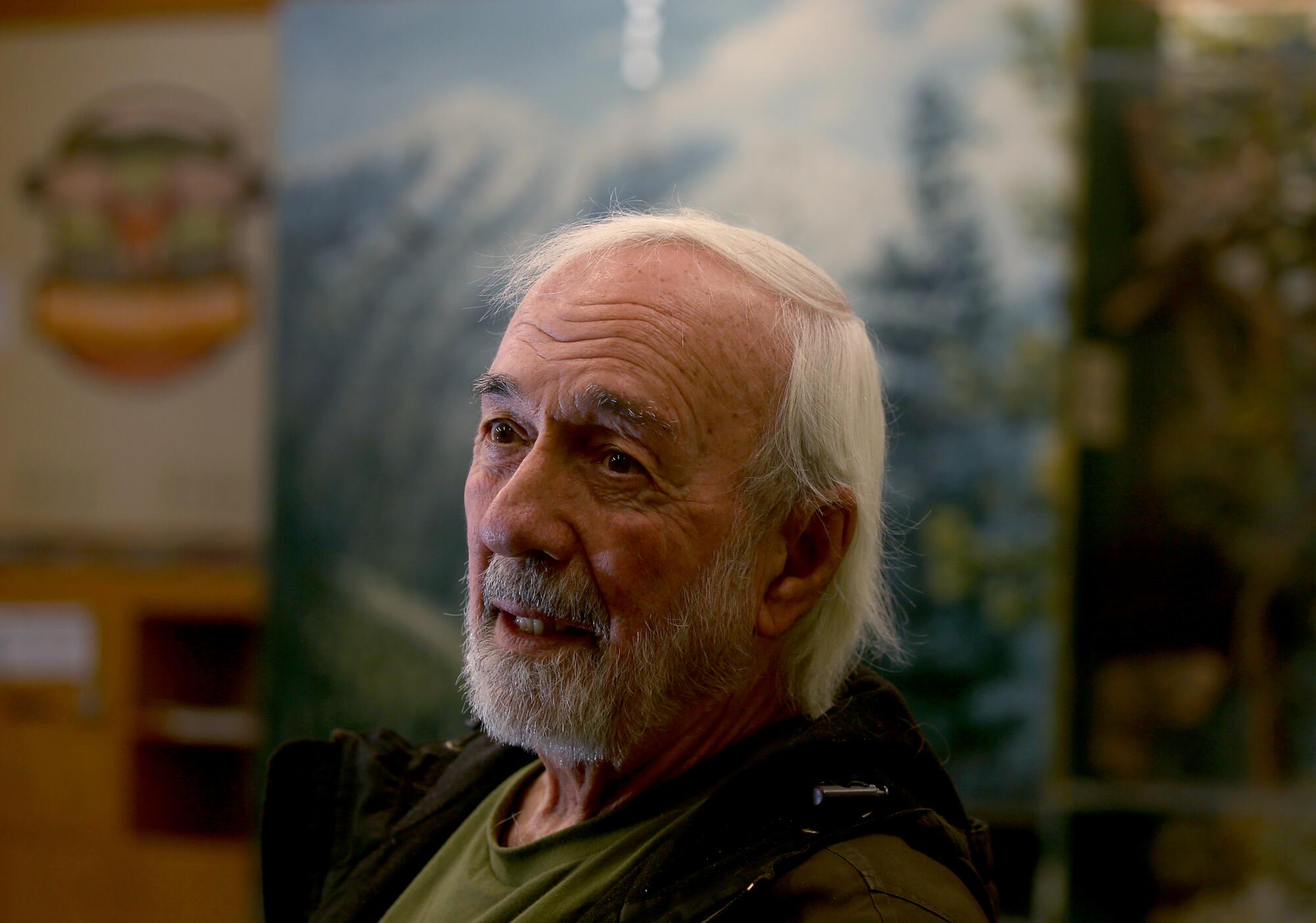

The unceremonious end of Robert Everett’s decades-long career as a pioneering wildlife rehabilitator came without warning recently as state investigators appeared suddenly at his San Dimas home.

After answering a sharp rap on the door early one morning in late October, the 80-year-old said he stood on his porch as California Department of Fish and Wildlife officers “came in, narco-style,” and began evaluating his injured, diseased and orphaned avian patients to determine which ones should be released, transferred elsewhere or euthanized.

Everett, who had just been discharged from the hospital and was learning to self-administer antibiotics intravenously in both arms, said he looked on with “shock and awe” as a peregrine falcon, red-tailed hawk, great horned owl, barn owl and saw-whet owl that he used as “educational animals” in school presentations and to attract donors were taken away.

“They shut me down,” he said.

The enforcement action at Wild Wings of California — which Everett and his supporters described as a raid — has sent shock waves through Southern California’s close-knit community of wildlife rehabilitators. For decades, Everett and other rehab operators have stretched shoestring budgets and rallied ragtag groups of volunteers to care for the region’s injured and abused wildlife, including bald eagles, barn owls, geese, pelicans, foxes, bobcats, raccoons, squirrels, sea lions, tortoises, lizards and snakes.

But as California officials conduct a review of regulations concerning the possession of wild animals, Everett and other members of the rehabilitation community say the state is cracking down on small, independent facilities — many of which were created in the 1970s and ’80s to deal with the growing problem of animals that are wounded due to human encroachment. They say the enforcement actions are causing aging rehabilitators to throw in the towel, and will leave countless injured wild animals without help.

In a conservation battle that pits native vegetation against imported deer, Catalina Island residents say they’ll take venison over ‘stupid plants’ any day.

“There’s a perception that the department is cleaning house, ” said Ann Reams, founder of Wildlife Care of Southern California, in Sylmar.

Reams claims authorities have conducted multiple inspections that have left well-respected rehabbers “intimidated and traumatized,” and she has authored a petition to curtail the enforcement actions.

Wildlife are being confiscated and euthanized, while rehabilitators are being forced to abandon their work, she says. Rehabbers, she insists, are being treated like criminals and have not been given any time to address the alleged violations or the opportunity to explain their circumstances.

“Whatever happened to a slap on the wrist?” she said.

State wildlife officials deny that they are singling out rehab operations for punishment.

Jordan Traverso, a spokeswoman for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, said, “There is no crackdown. But there is possibly a feeling of one based on the fact that there is still some catching up to do — our staff was unable to conduct routine inspections during the COVID pandemic. So, there is a backlog and we are addressing it.”

California’s oldest tree, a Palmer’s oak thought to be 13,000 to 18,000 years old, may be threatened by a proposed development, environmentalists say.

Everett started Wild Wings with his late wife Judy in 1978 after a neighbor had inadvertently tossed a nest containing three baby mockingbirds into a barrel along with a load of lawn trimmings.

For the couple, it was the beginning of a career of working together in their home as part of a sprawling network of veterinarians, volunteers, and licensed individuals who stay in steady contact with one another, often swapping accommodations, medicine and know-how to provide care and shelter for suffering animals until they can be returned to the wild.

The effort cost the couple about $50,000 a year to buy rodents from pet stores, laboratory animal dealers and feed stores to nourish their birds of prey. The Everetts struggled to meet expenses by securing donations from local supermarket chains and Southern California Edison, and by contracting with schools to give conservation lectures, during which they displayed permanently disabled birds.

They also won permission to build enclosures at the nearby San Dimas Canyon Nature Center for some of their injured owls, eagles and falcons. (The nature center will now care for birds that have been confiscated from Wild Wings. Everett will be allowed to work at the nature center as a docent, according to Noemi Navar, a Los Angeles County Fish and Game warden.)

Everett came to the attention of state wildlife authorities after his wife’s death earlier this year. They say he expressed an interest in transferring some of the birds in his care to Los Angeles County Parks and Recreation facilities.

“The county could not take those birds without permission from us,” said Heather Perry, wildlife rehabilitation coordinator for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

A review of the records on file, however, revealed that Wild Wings’ permit was issued in Judy Everett’s name. “That permit became null and void when she passed away,” Perry said.

Perry said she then asked law enforcement to go to Wild Wings and take an accounting of the birds. Officials said they tried to be as understanding as possible.

“We appreciate all the years of service he has provided as a rehabilitator,” said Vicky Monroe, conflict programs coordinator for the wildlife department.

The episode has had a chilling effect on the operations of other rehabilitation outfits, supporters say.

Reams, who specializes in treating native mammals with the exception of bears, deer and mountain lions, said she is not among those under investigation. But in a related matter, Duarte and Glendora have warned her to stop treating coyotes in the field for mange by feeding them raw meat and dead rats spiked with a medication, according to documents filed by city attorneys in both cities.

“I’m not doing that anymore,” Reams said.

Earlier this year, Linda York shut down her 37-year-old Coachella Valley Wild Bird Center, in Indio due to health problems. Ann Lynch, 81, founder of Southbay Wildlife Rehab in Rancho Palos Verdes, said she is challenging a criminal charge lodged against her operation by wildlife authorities.

Camella Wells, a spokeswoman for the 20-year-old California Council for Wildlife Rehabilitation, which is dedicated to advancing rehabilitation and supporting wildlife, declined to comment. Enforcement or investigation of permittees, she said, “is outside the scope of our mission.”

The controversy comes at a time when state wildlife authorities have begun the process of revising Section 679 of the California Code of Regulations, which allows for the possession of native animals for rehabilitation purposes. Final approval by the California Fish and Game Commission is expected sometime in 2025.

“In general, I think these changes to the regulations are going to bring us into a new era of professionalism,” said Rebecca Dmytryk, director of the nonprofit Wildlife Emergency Services, based in Monterey. “The process may be painful, but in the end, I think it will be a benefit to our profession and those we serve — California’s wildlife.”

Dmytryk said that there have been many “outrageous violations over the decades,” instances where licensed rehabilitators have done a disservice to their patients by keeping them alive and prolonging their suffering, when “the animals should have been put out of their misery.”

Plans to build a $200-million water pipeline across the Mojave Desert to supply the city of Ridgecrest are angering environmentalists, farmers and miners.

Some volunteer rehabilitators have come under investigation for illegally taking injured raccoons home to play with them as pets, and for dressing great horned owls up in Halloween costumes, authorities said.

The big question now is whether there will be enough wildlife rehabilitation centers left to “handle the overflow of native animals in need,” said Michael Chill, of Pasadena, who has spent decades working on the front lines of wildlife rehabilitation in the Los Angeles area.

Large, well-financed facilities such as the California Wildlife Center in Calabasas and International Bird Rescue in San Pedro are expected to remain in operation. But whether there will be people with the resources and training needed to safely transport “injured and sick animals to those centers remains uncertain,” Chill said.

Human activities and extreme weather events triggered by climate change are responsible for the deaths and injuries of billions of animals each year, according to a recent analysis of 674,320 digitized records from 94 wildlife rehab centers across the United States and Canada.

The findings, published in the journal Biological Conservation, identified major threats to over 1,000 species including iconic and threatened bald eagles, brown pelicans, big brown bats and common loons.

Window, building and vehicle collisions, as well as lead and pesticide exposure due to hunting with lead ammunition and rodenticide use, were listed as among the top threats.

“Across all species,” it says, “wildlife rehabilitators were able to return about a third of treated animals back to the wild.”

Meanwhile, the total number of wildlife rehabilitation facilities across Southern California has been falling since 2019. That’s when the long-struggling and high-profile Wildlife Waystation in the Angeles National Forest shut down after 43 years and began collaborating with state officials to relocate 470 mostly exotic animals.

“It took us years to rehouse those animals,” Traverso said. “We don’t want something like that to happen again.”

But behind the fences of dozens of local wildlife rehabilitation centers that live and die on the donations of others, “everyone is on pins and needles, waiting for a warden to knock on their door at dawn,” said Jim Vrieling, 87, who, along with his wife, Trudy, has successfully treated and released hundreds of raccoons at their Second Chance Critters facility in Los Angeles.

“It’s time to retire,” Vrieling said.