Some say ‘hazing’ stops coyotes from becoming urbanized. Biologists aren’t so sure

- Share via

Research scientist Niamh Quinn approached with caution as an intelligent predator with a long, narrow muzzle, sharp teeth and yellow eyes peered at her from the grip of a trap, awaiting its fate.

As was its habit, the 29-pound young male coyote had been prowling the streets of a Hacienda Heights neighborhood at 4 a.m. on Oct. 8 when it was drawn toward a compelling scent of rotting dog food.

Suddenly a spring-loaded mechanism threw a non-choking cable loop around its head, securing the yapping, confused animal.

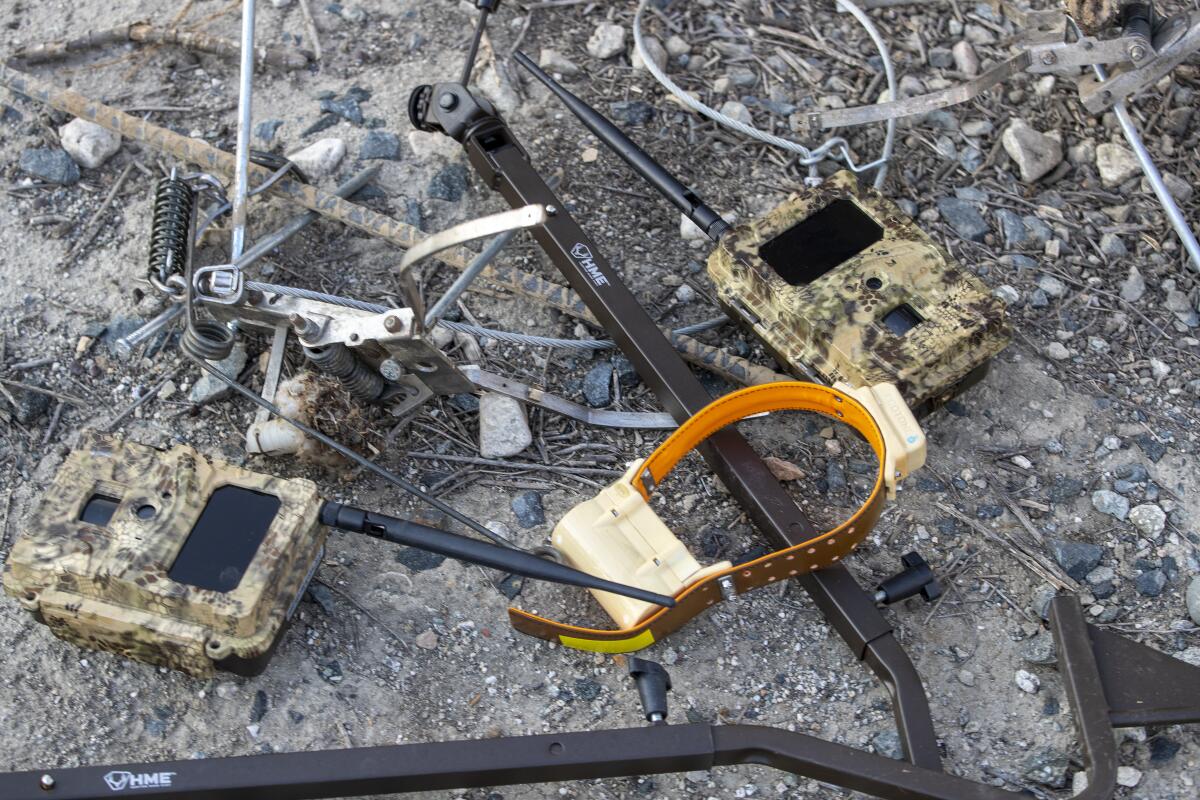

It was sedated, radio collared, tagged on one ear and assigned an identification number, 19CU001. Then it was released as part of a study led by Quinn to determine whether hazing techniques — shouting, bright lights, waving arms, for example — can effectively keep big-city coyotes away from homes and urban areas.

Several cities across Southern California have adopted and endorsed hazing techniques, at the urging of animal rights groups, but some scientists say it has done little to prevent the region from becoming the nation’s top coyote conflict zone.

“There is no scientific evidence that hazing alters the behavior of urban coyotes,” Quinn, UC Cooperative Extension’s human-wildlife interactions advisor, said on a recent weekday while inspecting a network of traps her team had set east of downtown Los Angeles. “Yet, it is being pitched as a good option for coyote management.”

“We want to figure out when, where and for how long it actually works, or if it even works at all,” she said. “For the sake of our communities, and coyotes, too.”

Coyotes are thriving throughout this metropolis of 20 million people and are breeding — oh, how they are breeding. While there are no estimates of the region’s coyote population, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates there are 250,000 to 750,000 of these animals statewide.

They are highly adaptive scavengers, part of the West’s natural heritage, but if their number proliferate too high amid cities and suburbs, the result too often is savaged carcasses of cats and dogs and attacks on humans.

And killing them doesn’t necessarily reduce their numbers. Studies show that remaining females in those situations produce litters with more pups. Their numbers bounce back to normal within a matter of months.

At least 49 people have been bitten by coyotes in Los Angeles County alone since 2011, about half of them in communities east of downtown, according to the county Department of Public Health.

Twelve people were bitten in the Elysian Park area in 2015, and most of those attacks were unprovoked, the department said. Victims included a jogger, a child who had been playing with friends and two people who were sitting on the ground and looking up at the stars.

The motivation behind those attacks is unclear. But David Drake, a wildlife biologist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Urban Canid Project, ventured a guess.

“The fact that so many attacks occurred in one area over the course of one year and then tapered off suggests they may have involved a lone rogue coyote that had lost all fear of humans,” he said, “or an aggressive transient male that moved out or got hit by a vehicle.

“Overall, however, more people are bitten by coyotes in Southern California than anywhere else — it’s a phenomenon unique to that region,” Drake said. “No one knows why this is happening, exactly. But you just don’t see that in other parts of the country.”

A 1981 attack on a 3-year-old Glendale girl is the only documented case in the country of a coyote killing a person. Since then, coyote management has been a flashpoint of contention between supporters of traditional methods of control — such as using firearms, poisons or asphyxiation — and groups advocating nonviolent techniques.

Groups such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and Project Coyote seek to promote co-existence, enforcement of laws prohibiting the feeding of wildlife, and development of a system for determining the proper responses to encounters with coyotes. The responses range from hazing to elimination of a coyote involved in documented attacks on humans.

“Anecdotally, hazing has been found to be effective in reducing conflicts and pushing problem coyotes out of certain areas,” Camilla Fox, founder of the nonprofit Project Coyote, said. “But there hasn’t been a lot of scientific study about what we can do to mitigate conflicts with the most persecuted, misunderstood and maligned carnivores in North America.”

“That’s heartbreaking,” she added, “because we have so much to learn from this incredibly intelligent ubiquitous species, one that challenges us to take a close look at our own behavior and what it really means to live with our wild neighbors.”

Quinn agrees, up to a point. Much of the historic dissonance between humans and coyotes, she ventured, might well be traced to mistakes and mistreatment of the stealthy creatures by humans, not the other way around.

“We have a lot to learn about these ultimate survivors,” she said. “They are not an endangered species, so there is no estimate of their population density, or even an understanding of how they use habitat.”

This much is certain: Coyotes are impressively opportunistic canids.

Quinn has studied the stomach contents of hundreds of urban coyotes that died across Los Angeles and Orange counties. Her research reveals they feed on a smorgasbord of cottontail rabbits, birds, avocados, oranges, peaches, cats and an occasional dog. They also tolerate the taste of candy wrappers, fast-food cartons, shoes with rubber soles and hiking boots.

Quinn’s new study aims to trap, collar and then release 20 coyotes across the landscape of neighborhoods, freeways and parks east of downtown, then closely monitor their wanderings, feeding habits and responses to various hazing regimes.

Their stories will help pave the way for the development of a science-based regional management program, she said.

“We’ve enlisted a small army of volunteers and residents, to help us determine, for example, whether hazing works once or twice on, say, an individual coyote, or not at all on others,” she said.

Researchers have set traps amid the undeveloped slopes, irrigated lawns, dumpsters around the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department headquarters in Monterey Park, with the blessing of state wildlife authorities.

On a recent weekday afternoon, tires crackled over dry tumbleweeds as Fernando Barrera, a county wildlife specialist and state licensed trapper, stopped his pickup near the department’s communication towers, pulling the day shift of coyote patrol with Quinn onboard.

The ground was covered with coyote prints and scat. But no predatory eyes returned his stare, this time, from an expanse of brush where he had recently spotted a pack of five coyotes following the scent of food or, perhaps, searching for hidden accommodations in which to raise new generations of pups.

“They might be miles away or right around the corner,” Barrera said, looking out at the horizon with a smile, “just trying to make a living in the Los Angeles area.”