Angered by climate denial, a Times photographer embarked on a watershed journey

- Share via

This is the July 14, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Good morning. I’m Stuart Leavenworth, editor of Boiling Point, filling in for Sammy Roth. He will be back in two weeks.

It was late 2020, less than a year into the pandemic, but Luis Sinco wasn’t thinking about COVID-19. He was overwhelmed by catastrophe.

Fires were burning, glaciers were melting, and the West was again in drought. But from talking to his kids and friends and people around him, the award-winning Times photographer sensed little dire urgency, little connection between the climate crisis and the routines of everyday life.

“It occurred to me — people think of water as something that just comes out of your tap. They have no idea of the source of that water,” Sinco told me the other day. “Just think about that.”

So, Sinco focused his sights on a lifeline of the West — the Colorado River.

It’s a watershed of stunning landscapes that serves 40 million people but has been over-tapped for decades, a prospect that the explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell foretold more than a century ago. In 1893, the prescient Powell warned that exploitation of the Colorado would create “a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not enough water to supply the land.”

Sinco couldn’t easily find a reporter to help him capture the story he imagined, so he set off on his own. In between assignments, he traveled roughly 1,500 miles, from the river’s headwaters in the Rocky Mountains down to where the Colorado once regularly reached its terminus, in the Sea of Cortez in Mexico.

During his travels, Sinco sought out locations that anyone could access, to provide a tourist’s-eye view of the river. His final galleries were supplemented with aerial drone images shot by Brian van der Brug of The Times. Together, the photographs capture the vast expanse and diversity of the river basin, from the first drops of snowmelt to its sinuous course through red-rock canyons to the ephemeral pleasures it now hydrates: casino fountains in Las Vegas, lettuce fields in the Imperial Valley desert, lush lawns in Phoenix and Los Angeles.

Sinco, who has been a Times staffer since 1997, has contributed to three Pulitzer Prize-winning projects — coverage of the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the 2004 California wildfires and the 2015 terrorist attack in San Bernardino. He also was a Pulitzer finalist for his photographs during the battle of Fallujah in Iraq, where he captured an iconic war image, of the “Marlboro Marine.”

This interview with Sinco has been edited for clarity and brevity:

ME: What made you choose the Colorado River for a photographic statement about climate change?

SINCO: I was thinking, wow, imagine all the visual possibilities — the chance to really catch someone’s attention and to show: Here’s this really majestic and fragile thing. So much amazing nature. What are we going to do about it to make sure it is there in the future?

I mean, people turn on their faucets in L.A., San Diego, Las Vegas, wherever. They have no frickin’ idea. They just have no idea where that water is coming from.

ME: Had you spent much time in the greater watershed before you did this project?

SINCO: No, there were many parts that I had never been to. I’ve never been to Grand Junction, Colo. I’ve never been to Moab [Utah] or Monument Valley. I’d been to the Grand Canyon, of course, and Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Just from there, I knew that this was a big, big, big thing, right? You look at the Grand Canyon, and you go, “That was carved by millions of years of water.” It’s just spectacular. I saw it as a vehicle to get people interested in this river — not just as essential to our water supply but part of our cultural and natural heritage.

ME: So how did you choose where to go? You could spend five years in the Colorado River Basin and not come close to seeing everything.

SINCO: I just basically followed the course of the river. Much of it is inaccessible except by boat or by helicopter or some of the dirt roads, but I didn’t want to go that route. I basically thought — I’d like to access the river the way everybody else accesses the river. It doesn’t take a special $2,000 boat trip down the Colorado River to appreciate it, right? It’s the most spectacular scenery in the world. The photos end up taking themselves.

ME: I reported from Lake Powell during the early parts of the Colorado River drought, in 2002. So many otherworldly landscapes were revealed in Glen Canyon, and more so now. Whom did you see as your audience for this story?

SINCO: You have to pull people in. You have to make people look. We are in an age where Instagram tells so many stories. It is very visual. These days, you can do a five- or six-part series, but not even my kids are not going to put up with that anymore. It’s about the imagery, and you’ve got it all there with the Colorado River.

ME: During your trip, was there a particular place or photo that stood out for you?

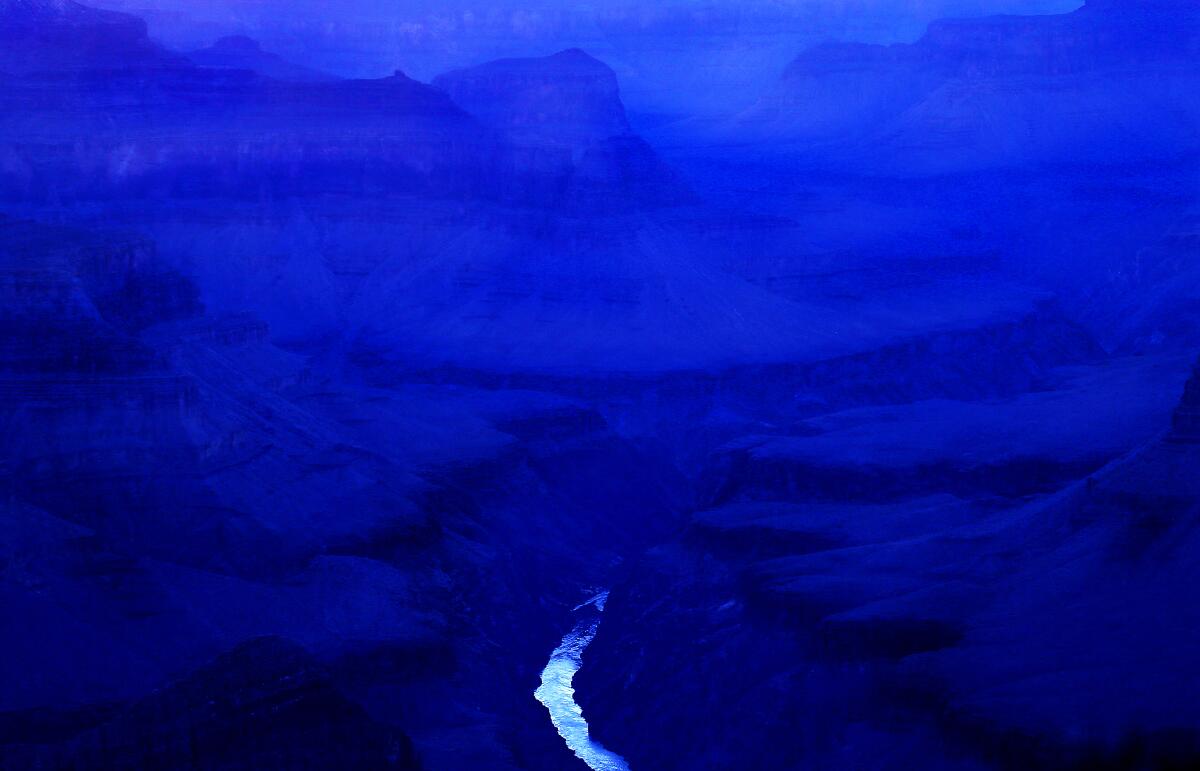

SINCO: That lead shot with the Grand Canyon all in blue. Yeah. It tells you the story, right? It’s just like — look at this little skinny thing that’s like cutting across all this arid rock, at dusk, you know, and you have that bluesy feel about uncertainty, right?

And that was my agenda. That photo was taken at the most accessible point of the river. The Hopi Viewpoint (on the canyon’s South Rim). Everybody can see this, right? It’s not like I made some special arrangements to see something that nobody else has seen in like 100 years. That’s not the point. The point is, let’s show what other people can see, and put a little spin on it as they go. Hey, isn’t this special? Isn’t this fantastic? Isn’t this endangered?

ME: You went all the way down to the Sea of Cortez. What were your thoughts on reaching that endpoint of the river?

SINCO: I was thinking about so many things, including all the driving I was doing and the fossil fuels I was using. But as for the river not reaching the sea, that is so common. [For decades, so much water has been diverted to supply farms and cities that the Colorado River rarely reaches the sea.] It happens pretty regularly, and yet, you know, upstream we are not even thinking about that or what we could do. Maybe we should take much, much shorter showers. Maybe we should stay home for vacation instead of pouring more carbon into the air.

ME: Other thoughts on the series you wanted to share?

SINCO: That is pretty much it. Everybody has to have a better sense of urgency about the environment. We are reaching feedback loops with the climate, where problems just feed on themselves. We need to start paying attention, and we need to start making real sacrifices. Tear out your freakin’ lawn, for God’s sake!

We live in a world of distractions. Everyone is on their phones. Our attention keeps getting pulled from one thing to another. How are we ever gonna get right with the environment if somebody is always, like, pulling our attention somewhere else?

And, on that note, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

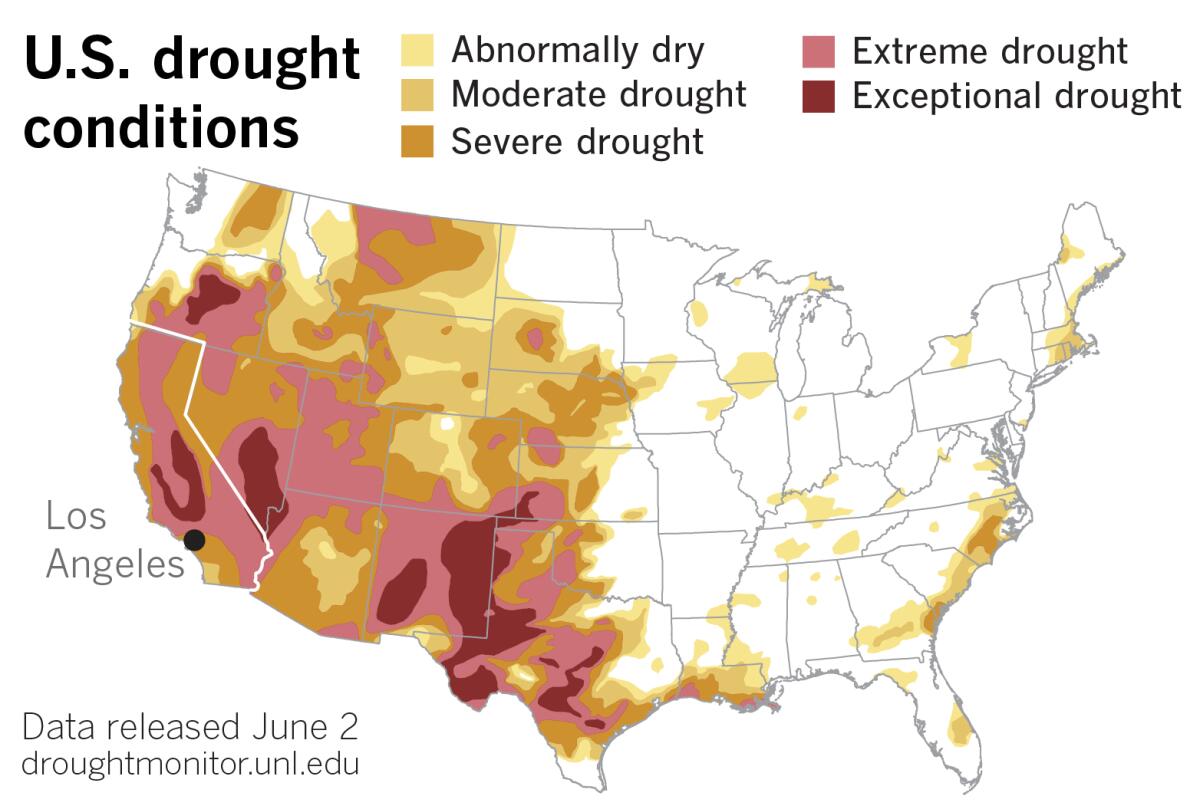

To cope with climate change and protect yourself from it, tracking is vital. To that end, The Times’ Sean Greene and Thomas Suh Lauder have launched a first-ever California drought tracker, with detailed information on the status of water reservoirs, soil moisture conditions and water usage for communities statewide. From it, I learned that customers of the East Bay Municipal Utility District, where I now live, use more water per capita daily than their counterparts in Los Angeles. That surprised me — given the water I’d regularly see flowing off lawns in Mar Vista, my previous home turf. Check out the tracker to learn about your neighborhood.

Which California communities are most at risk from heat waves? There also is a tracker for that, courtesy of the UCLA Center for Public Health and Disasters. The mapping tool reveals that extreme heat is fueling more than 1,500 excess emergency room visits per “heat day” in L.A. County, my colleague Hayley Smith reports. For more information, be sure to read The Times’ prize-winning investigation on extreme heat from last year.

Big Soda is so addicted to plastic it will have trouble meeting its pledges for reducing climate impacts. That’s a key finding from a startling deep dive into Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and other soda companies by Bloomberg’s Ben Elgin. Each year in the United States, these companies produce about 100 billion plastic bottles. But the recycling rates for these containers are dismal, resulting in more fossil fuels needed to produce more plastic bottles, and on and on it goes.

FIRE IN THE WEST

The Big Trees may catch a break from the flames. As of Wednesday, Yosemite National Park officials were growing confident that the Mariposa Grove of ancient sequoias would survive yet another blaze threatening some of the world’s oldest living things, as The Times’ Hayley Smith and Gregory Yee reported. That followed an all-out battle Monday against the Washburn fire, which is spewing smoke as far north as the Tahoe Basin, Gregory Thomas and Dustin Gardiner report for the San Francisco Chronicle.

A Yosemite thinning project? Or logging project? As it turned out, the Washburn fire exploded just after an environmental group obtained a federal court order halting a forestry project in Yosemite. Parks officials said the project was aimed at reducing flammable fuels, but critics said it was a logging project disguised as something else, The Times’ Felicia Alvarez reports.

Like everyone else, runners will have to adapt to climate change and wildfire smoke. Although running is good for one’s health, outdoor athletes are at increased risk of breathing in particle pollution, and are having to adjust their training routines in the Bay Area and elsewhere in California, Chasity Hale reports for the Chronicle.

WATER IN THE WEST

And now for some good news on the water front. Conservation messages seem to be having an impact in Los Angeles, as water demand dropped 9% in June compared with the same month last year, the Department of Water and Power reported. It was the lowest water use for any June on record, according to this story by Hayley Smith.

And now some more good news on the water front. Golf courses don’t necessarily need to be heavily irrigated sponges for water that lack any benefits for wildlife or the environment. Bloomberg’s Todd Woody has this insightful story on the re-wilding of a Marin County golf course, where streams are being uncovered and native grasses planted.

Can water witchcraft actually help find hidden underground H2O? The Times’ Steve Lopez had to sweat that question after one of his sprinklers broke and he had trouble locating the source. A Pasadena city troubleshooter showed up, and suddenly Lopez was plunged into the world of water dowsing, as he chronicles in this column.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

California’s plan to capture carbon as part of a broader climate strategy is coming under fire, but it also has some supporters. The Times’ Tony Briscoe examines the pros and cons with Gustavo Arellano in a recent episode of The Times podcast.

What are the economic costs of climate emissions? The United States and China are each responsible for more than $1.8 trillion of global income losses from 1990 to 2014, according to a new Dartmouth College study, reported by the Washington Post’s Steven Mufson. The report links the emissions in individual countries to the economic impacts of climate change in others, and could bolster lawsuits claiming harm caused by global warming.

Five cities in the Bay Area are banning new gas stations. The move opens a new front in California’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions and is coming under fire from the oil industry, The Times’ Grace Toohey reports. In Los Angeles, City Councilman Paul Koretz has proposed that L.A. work toward its own ban on new gas stations.

ONE MORE THING

“Tear out your freakin’ lawn, for God’s sake!”

That quote, from Luis Sinco above, illustrates one approach to water conservation. But sometimes the carrot is more effective than the stick. In this touching and lovingly detailed piece, my colleague Lisa Boone explores how transforming your front yard can be a form of therapy, a source of hope and a gift that keeps giving back, often in unexpected ways.

That’s been the experience of Seriina Covarrubias, the focus of Lisa’s story. Mourning the death of her father and wanting to honor him, Covarrubias and her husband tore out the Bermuda grass in their Altadena frontyard and replaced it with native plants. Now the couple has birds nesting and butterflies flitting about. Neighbors stop by to take photos of their new pollinator sanctuary. Beauty has a way of sparking conversation.

Covarrubias suffers from a chronic illness, so she can’t always go outside to dig in the dirt and smell the roses. But there are roses. She planted a Burgundy Iceberg variety in memory of her father.

It takes money and labor to attempt such a conversion, but for the Altadena couple, the payoff has been worth it, and that doesn’t count the cheaper water bills.

As Covarrubias put it: “It gave me something to take care of that wasn’t myself.”

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.