Analysis: On issue of race, Grammys leap past the Oscars, then stumble

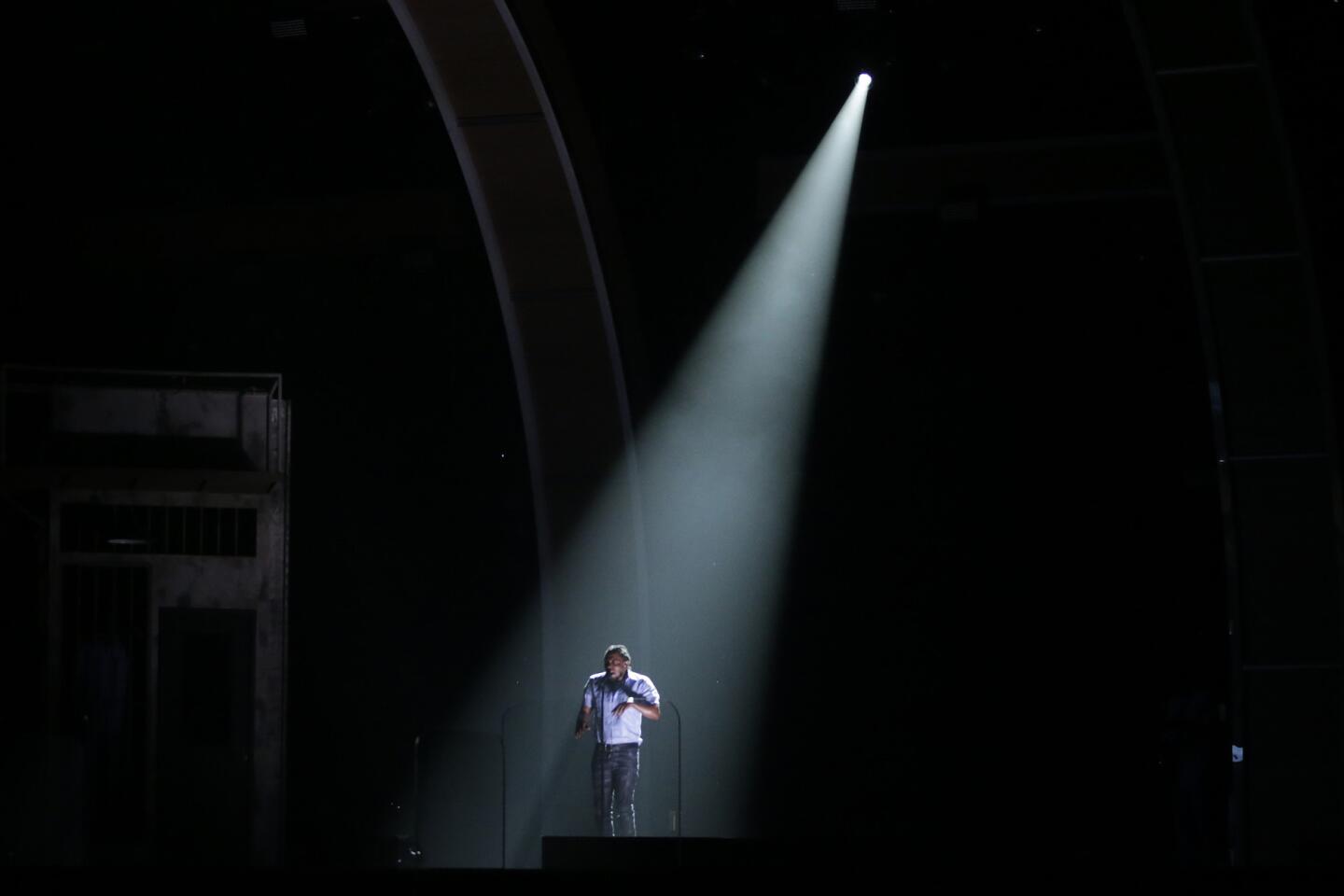

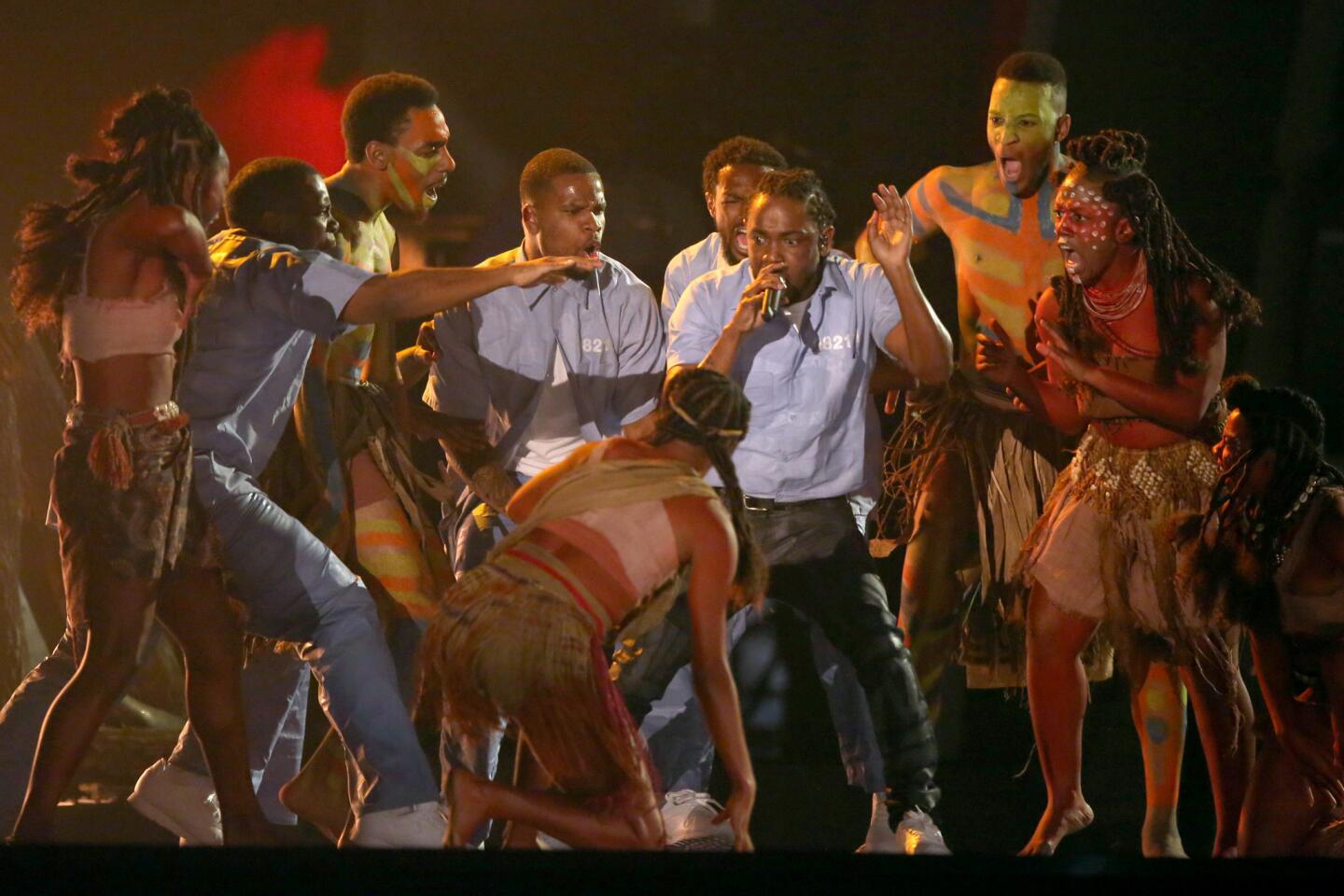

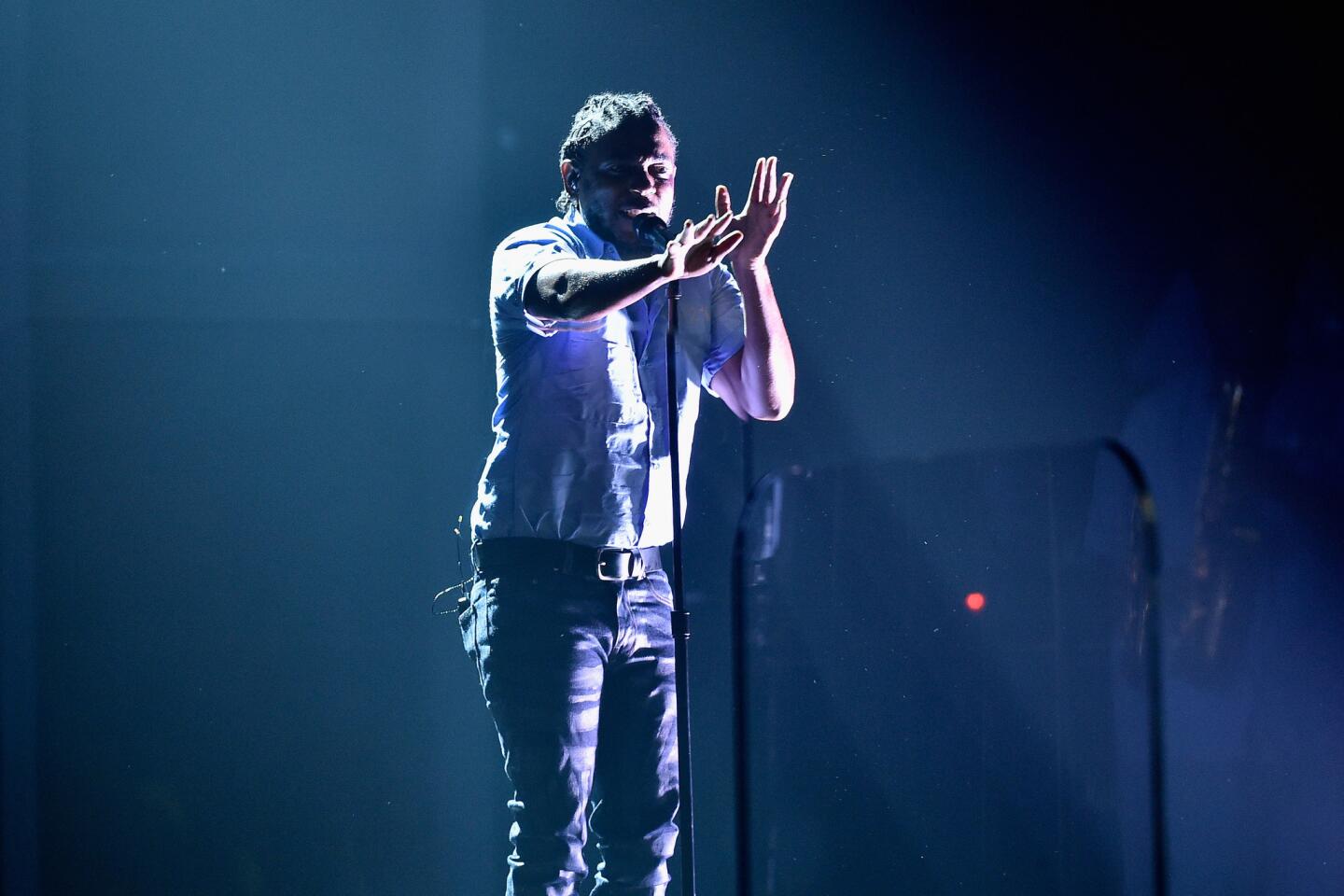

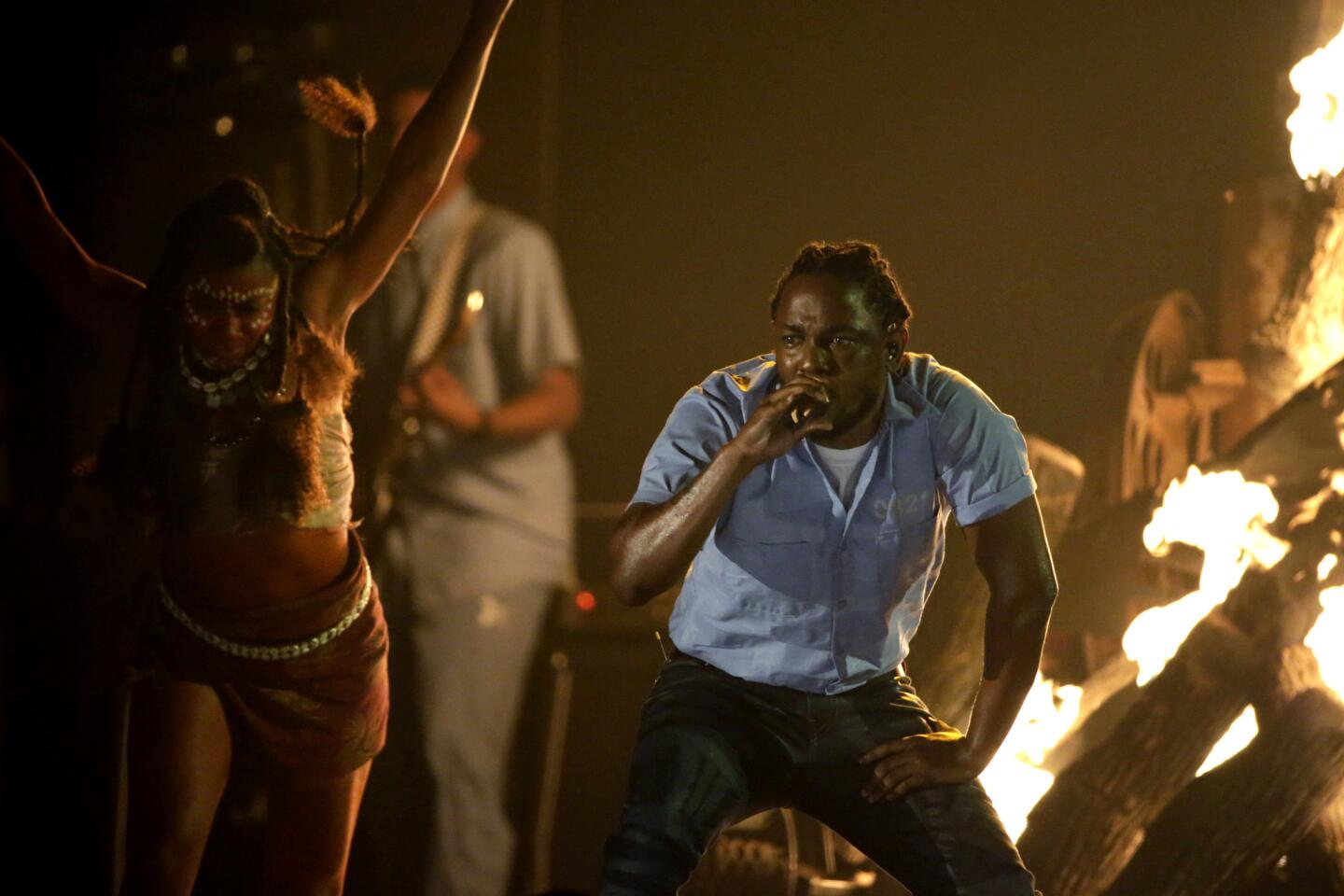

Kendrick Lamar performs at the 2016 Grammy Awards.

- Share via

When the big day arrived, the Grammys, unlike the Oscars, got past questions about race.

Until it didn’t.

For much of its 3 1/2-hour running time, music’s big evening provided a template for how the Academy Awards — and indeed, many of the kudos telecasts that invade our airwaves and commandeer our weekends this time of year — might reach across the diversity divide.

It’s been a difficult time on the issue of racial representation in entertainment — one of high awareness but insufficient action — but the Grammys initially seemed to dispel the challenges with enviable ease.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

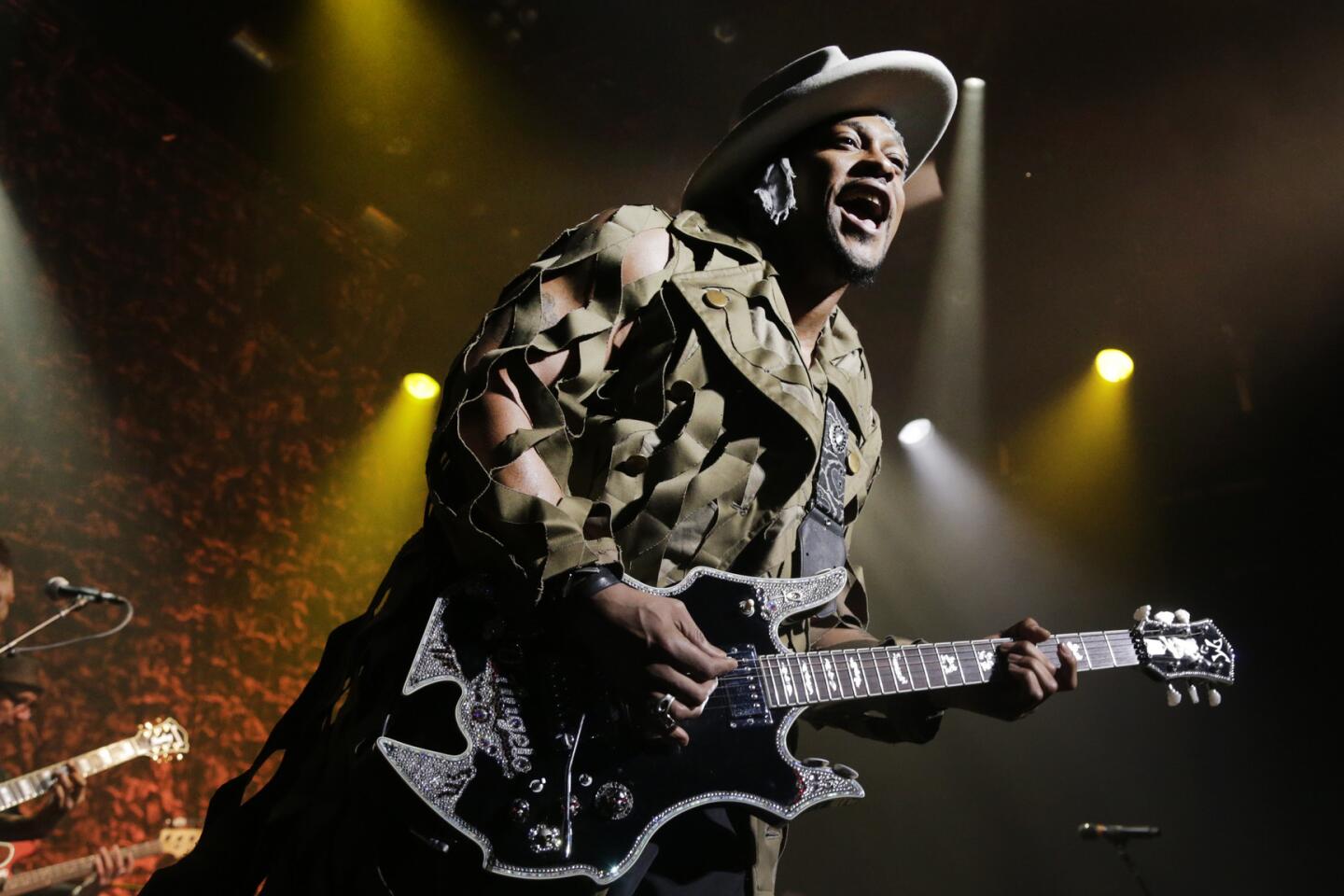

Brittany Howard, the mixed-race frontwoman of the soul-fried rock band Alabama Shakes, led a strong rendition of “Don’t Wanna Fight” as her group won three Grammys, including best rock performance.

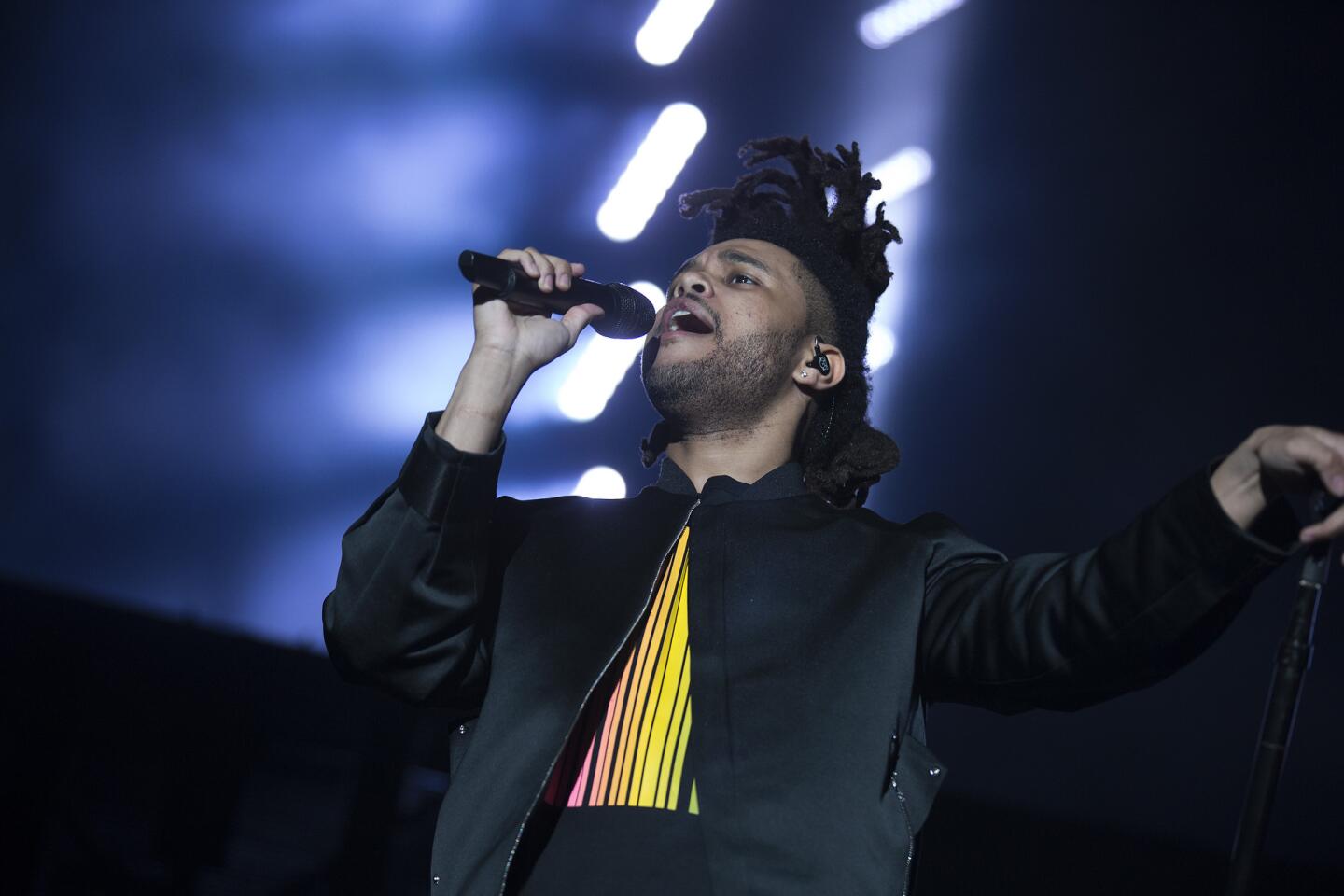

The Weeknd was similarly strong, after he escaped from a Lite-Brite prison, offering a solid medley near the top of the show and also winning best urban contemporary album for his sophomore effort, “Beauty Behind the Madness.”

The most exciting live moment of the night came when the mixed-race cast of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton” gave a hair-raising performance from the Richard Rodgers Theatre in New York, then soon after won best musical theater album. Miranda, of course, rapped his acceptance speech.

And then there was the urgent and weighty performance by Kendrick Lamar, six explosive minutes that began with his appearing as part of a chain gang to his song “The Blacker The Berry” and ended in a rapid-fire performance that featured actual flames, as well as a mix of Compton and Africa images. Lamar’s seminal record “To Pimp A Butterfly” won best rap album.

But then the biggest prizes of the night, the all-category ones, finally arrived, and the Grammys couldn’t get past the same hurdles that have haunted the Oscars.

Lamar was defeated for album of the year by Taylor Swift’s “1989.” (Swift, not missing a diplomatic beat, quickly went and hugged Lamar, saying, “I love you,” then turned it into an empowerment moment for young women. More on that in a moment.)

The Compton rapper’s song “Alright” — a protest anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement that also received center stage during Lamar’s six minutes — scored best rap performance and best rap song, but it couldn’t win song of the year. (That went to Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud.”)

Similar crossover problems afflicted The Weeknd, who couldn’t take album of the year honors either, while his hit single “Can’t Feel My Face” was defeated for best record. (That prize went to Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars for “Uptown Funk.”)

When all was said and done, the Grammys’ big trio of awards — record, album and song — all eluded black artists.

The tallies for African Americans Monday night were in the stratum of what many Oscar observers only wish for at the movies show. The trophies at Staples for black artists seemed to come in bunches; Lamar, for instance, scored five Grammys.

But these figures are misleading. Most of the wins were in categories in which African American (and Canadian) musicians are strong in the first place. Lamar’s victories arrived primarily in rap categories; his one win outside that realm, for best music video, came with the help of Swift and her “Bad Blood.”

In a hypothetical alterna-world — one in which, say, Taylor Swift was a rap force, or where black artists were regularly country juggernauts — wins for black artists in genre categories would seem significant. As it is, a triumph for Lamar in a category like rap album feels limited at best. The biggest awards, the ones that everyone in the music industry covets, remained out of reach Monday night for black artists. (It’s worth noting that Mars, of Puerto Rican and Fillpino heritage, was part of Beyonce’s Black Panthers-themed moment at the Super Bowl.)

Lest this still seem like progress from where we’ve stood recently, it’s not. In fact, matters may be getting worse.

Oscars 2016: Full Coverage | Complete list | Grammys 2016: Full coverage

Over a 15-year period that began in 1991, African American artists won album of the year at the Grammys six times — a sonically diverse group that included Outkast, Lauryn Hill, Quincy Jones and Whitney Houston.

Yet in the past 11 years, an African American artist has won best album only once. That was in 2008, when Herbie Hancock took the prize — for a tribute album to Joni Mitchell.

The (less-comprehensive) record of the year prize showed a similar dip — four wins for African American artists from 1991 to 2005, then only one in the past decade.

At least the Grammys can take solace in the fact that they’re not the Oscars. The annual movie awards extravaganza, which will hand out its prizes in 12 days, has fared even worse in this regard during the modern era. Over the same 1991-2005 period, a movie with a black lead character won best picture only once (“Crash” in 2005.) In the decade since, only one other such film (“12 Years A Slave”) managed to end up with the best picture Oscar. (Hey, at least the number didn’t diminish.)

Music and movies are different art forms, and they come with different histories, different industries, different creative dynamics. But as Monday night’s festivities from Staples Center showed, they have some of the same challenges with regard to to mainstream showbiz acceptance.

Well, sort of.

When the #OscarsSoWhite movement gained new force last month, it threw a light on a pressing issue. Yes, there were no stories with black casts in best picture, and no black actors among the 20 nominees. But the problem was less that a host of worthy movies were snubbed by voters (with apologies to “Straight Outta Compton”) than the fact that there wasn’t a terribly diverse group of contenders to begin with. As several voters said at the time, they certainly weren’t looking past African American contenders on their ballots. If anything, “we would have chosen more black nominees,” they essentially said, “if only they were there for the picking.”

Members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, along with the film business it represents, have a problem creating a wide range of black-led movies. When it comes time for awards, they throw up their hands — not unreasonably, but not with fully intellectual honesty either — saying there wasn’t a worthy field of contenders from which to choose.

The Recording Academy and the music industry it represents have little problem offering up the art in the first place, as a look at the range of material from (and sales of) artists like Lamar, The Weeknd, Drake, Rihanna and a host of others demonstrates. And they’re interesting in nominating them for the top prizes and including them in the conversation; that shouldn’t be scoffed at But they still can’t seem to see fit to honor them with the year’s biggest prizes.

The movie business, in other words, has a production problem. The music business has an awards problem.

#OscarsSoWhite: The boycott, reaction and more

Skeptics (and worse) might say that evaluating awards shows through this lens is reductive. Voters at these ceremonies, they say, should be simply honoring “the best” of the year, and if they felt Swift’s album was the best, and/or better than Lamar’s, who are pundits to tell them otherwise? Like many who cover the entertainment business, I’ve received many emails to this effect, and look forward to many more.

But the argument of “best” seems to miss the point. For any given choice, sure, you can argue that one record happened to be better than another. But it’s hard to argue with a pattern. And when so many worthy albums over the past decade — we could list the output of Nicki Minaj, Beyonce, Drake, Wiz Khalifa, Pharrell, Jay-Z, Joey Badass, 50 Cent and plenty of others — don’t lead to a single best album, it feels like a pattern.

Part of this, it should be said, is what happens when rap and R&B, genres into which many African American artists fall, are segmented into separate categories. As my colleague Gerrick Kennedy wrote, the Recording Academy has a longstanding disinclination to name a rap album the best of the year, choosing instead to keep such material in dedicated categories. And it’s not like country has won the top prize much in the past decade, one might reasonably point out, though even artists from those quarters — the Dixie Chicks, Alison Krauss — have won more than rap artists.

Still, it’s becoming harder to argue that at least one of these records, year in and year out, isn’t “the best” — just as it’s getting tougher to make the case that with all of the talented black filmmakers out there, with all of the avenues for studio and independent financing, Hollywood can’t manage to eke out more than one or two high-end movies with black characters in a given year.

In some respects, the Grammys have figured out some puzzles that continue to vex the Oscars — not the least of which is that the key to a successful awards show may be handing out....fewer awards. The Grammys gave just eight in the live telecast Monday, an average of one barely every forty minutes, a low in the modern era. The mind dances and spirit tingles at how a similarly constructed Oscars would look.

Other lessons may not make their way into Oscar producers’ planning meetings. One doesn’t necessarily need, for instance, posthumous tributes to run the length of an entire show; at some point Monday night, the in-memoriam segments were hatching other in-memoriam segments.

And the Grammys telecast directors these days often seem to be one step short of setting up a Taylor-Cam, able to capture the star’s reaction to every win, loss and sneeze from the stage.

Which brings us back to that album of the year moment. Swift’s “I love you” wish to Lamar was quickly followed with a speech in which she said, “As the first woman to win album of the year at the Grammys twice, I want to say to all the young women out there: There are going to be people along the way who will try to undercut your success, or take credit for your accomplishments or your fame, but … just focus on the work and … don’t let those people sidetrack you.”

The remarks were a not-exactly-veiled dig at Kanye West, who, among other shots, has included an objectifying and derisive line on his new album about Swift, apparently without her permission, in which he implies that he helped launch her career with his infamous “I’mma let you finish” moment at the 2009 VMAs. (That’s when he assailed the awards for not giving Swift’s prize to Beyonce.)

As he prepared to release his long-delayed “The Life of Pablo” this weekend, West has taken to social media to stoke the flames on the issue of race and music — at one point Monday, he asked “Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, New York Times, and any other white publication [to] please … not comment on black music anymore.”

And then of course there was the memory of this time last year, when West jumped onstage during Beck’s win for best album at the Grammys, saying once again that Beyonce was snubbed and that the Recording Academy needed to “respect artistry.”

West’s methods are certainly polarizing. (He later apologized for the Beck moment.) But his message may not be as outlandish as his critics would like you to think. When so many great black artists can’t win album of the year, there’s a case to be made, and an objection to register, that something larger may be happening.

West was only a spectral presence at this year’s Grammys; even on Twitter, he didn’t crash the party as he could have, choosing instead to focus on his efforts to hit up Mark Zuckerberg for a loan.

Next year, with “Pablo” in contention, West could well be back in the room. And the question about black artists winning big awards, long unspoken, may not be as silenced.

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

ALSO:

Oscars 2016: Here’s why the nominees are so white — again

Kendrick Lamar didn’t win album of the year, but he’s still moving rap to a bigger stage

Review: The Grammys energy shortage

Grammys surprises: Adele’s bum notes, Nashville’s snubs

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.