Critic’s Notebook: The day I met Ethel Kennedy

- Share via

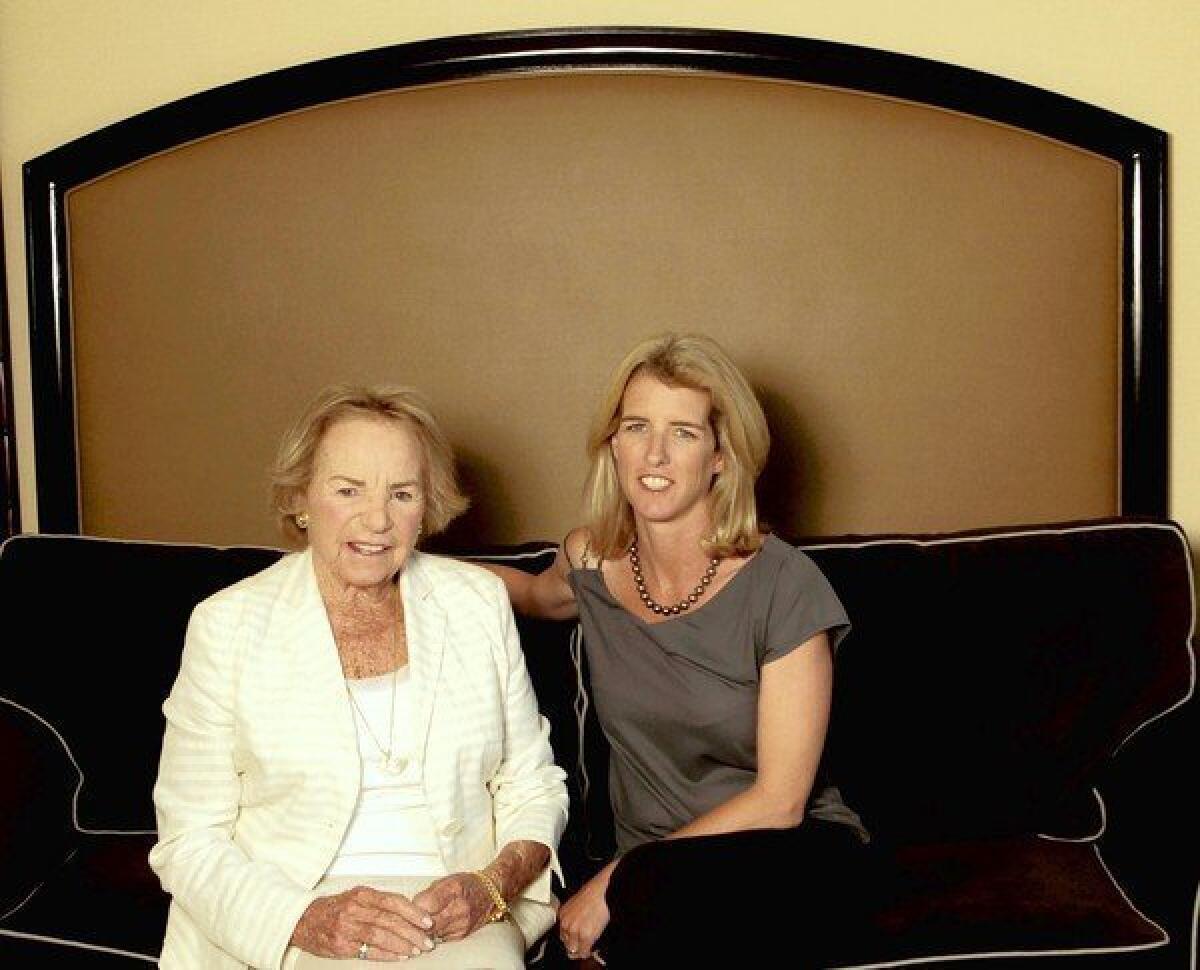

I go to the Beverly Hilton to interview Ethel Kennedy, the subject of a new HBO documentary, “Ethel,” which airs Oct. 18. The film is by her youngest daughter, Rory.

I walk through the door and there she is, straight up and picture perfect, and for one heart-stopping, utterly unanticipated minute I am 4 years old again, watching my father sob in our living room. He was always a big man, quiet and calm, but now his glasses are on the floor and his face is in his hands and the sound he makes is frightening enough to send me out the front door and onto a neighbor’s lawn.

This is the first truly vivid memory of my life. The day Sen. Robert F. Kennedy died. And now, here is his wife, offering me her hand.

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by The Times

She is a small woman but solid, especially beside Rory, who is tall and slim with those Kennedy eyes and the family smile. Ethel looks precisely like what she is — a well-dressed 84-year-old grandmother (and great-grandmother) who put on lipstick, some good jewelry and a smart ensemble to do something she isn’t especially keen on doing because her daughter asked her to.

She has bright and watchful eyes and she smiles at me, thanks me for coming. The first mouth-drying minute extends to a second minute and I am convinced that I will not be able to do this, to sit and calmly ask any of the questions I so cavalierly jotted down.

No, I am just going to sit here and stare at Ethel Kennedy while the tattered tapestry of my childhood unhitches itself from storage and unrolls inside my head.

PHOTOS: Hollywood back lot moments

It is impossible to overstate the role the Kennedys played in the lives of families like mine, Irish Catholic Democrats who saw the Kennedys as symbols of social revolution. Not just the final rending of all those No Irish Need Apply signs that haunted my grandparents’ memories, but a new breed of young politicians who demanded, from themselves and those around them, a life of service.

The Kennedys spoke of our moral obligation to help the poor and that responsibility extended to government. The faithful adults of my early memories — public school teachers, liberal priests and Peace Corps volunteers — all believed. To lose Jack was bad enough; for Bobby to follow so quickly and horribly was overwhelming. In our house, every president lived in the shadow of an alternative reality — what would this country be like if Bobby Kennedy had lived?

All of which came rushing back to me, with inconvenient intensity, within the cream-colored walls of the Beverly Hilton.

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by The Times

Fortunately, if you have done a thing often enough, there is part of the brain that takes over when other systems are failing. So for a few minutes I was able to conduct an interview while pretending I wasn’t having an incomprehensible emotional breakdown in front of Ethel Kennedy, and soon enough I wasn’t.

Ethel is a woman of few words, both in the documentary and in person. She answers questions directly but simply and is happy to defer to Rory, a successful filmmaker, who talks quickly and smoothly

clearly trying to make this day, in which there would be many interviews and a press panel to follow, as easy on her mother as possible.

While she does not deny that the timing of the film’s television release — weeks before Election Day — is not terrible, Rory says that resurrecting her father and the politics he espoused was not why she committed to the film. Not at all. Sheila Nevins, the president of HBO Documentary Films and with whom she has often worked, had suggested it.

Rory had previously shied away from chronicling her family, but she very much wanted to share her mother with the world. She did not think, however, that Ethel, who has turned down interview requests and book proposals for decades, would agree.

But she did. Because “Rory asked me to,” she says now. “And you can’t say no to Rory.”

Having seen the film, this is easy to believe. It is a joyful, loving and fascinating back-window view of an iconic family at a time of great social turmoil and political divisions, many of which remain today.

Not surprisingly, the most heart-wrenching moment comes when the family discusses the assassination. Ethel cannot, and her animated face goes still, almost blank. And though the narrative continues, with much focus on her strength, she does not come back until the chronology catches up to Rory’s birth.

“I was born,” Rory says.

“Yes,” Ethel answers, her eyes lighting up, “that was the joy of my life.”

This is close to where the documentary ends. Although Rory’s initial impetus had been to showcase the woman she has only ever known as a single mother, the film focuses almost exclusively on Ethel’s life with her husband, moving inexorably toward the day of the 1968 California primary and the Ambassador Hotel.

“When I started looking through the archival footage,” Rory says, “I realized that she was always there.”

She interviewed her mother for five days as well as all but one of her eight living siblings. They are, Rory says, a storytelling family, and it shows in the fond humor and easy cadence of tales oft-told — the menagerie at Hickory Hill, the letters “Daddy” wrote to each of his children at one point or another, the near mythic status of their parents’ love and “Mummy’s” stoicism.

“Mostly it felt like home movies,” Ethel says, which is true to a point.

But of course Rory knew going in that while much of the narrative is happy and hopeful, there were also “sensitive areas.” And she didn’t know how or if her mother would answer.

“I was a wreck,” Ethel says, with a self-mocking grimace. “It’s a very busy life. It was like when someone asks you to auction off a weekend in Hyannis and you say, ‘Fine,’ and then the day actually comes. Now what?”

For Rory it was a unique opportunity: to spend five days asking her mother about her life. Although it becomes clear in the film that the children are comfortable being open about the events of their lives, you get the sense that Ethel has kept the private narrative focused on her husband.

Everyone refers to “Daddy” as if he had died a year ago, or two; almost 45 years later, he remains a vital presence in the family. Ethel says she is not comfortable speaking in public or being photographed or answering questions about herself; in fact, her daughter admits, there was nothing about “this whole process” that her mother enjoyed.

How then to explain the years as a campaigning spouse, the thousands of people invited to her home, the endless appearances and photographs?

“I did that for wonderful people,” Ethel says. So it’s OK if it’s for other people? “Wonderful people,” she says with a gentle pointedness.

Did it feel, as it felt to many, during those turbulent years, that the country was running mad, falling apart?

“Sometimes,” she says. “But then there were 21/2 years when it seemed like change was possible.”

The spirit of the work her husband began is alive, she says, but “no one is talking about the poor [the way the Kennedys did], about helping people’s lives get better. We don’t have the leaders.”

She has never talked about that day when everything changed, she says.

“Everyone deals with pain at some point, why dwell on it?”

Others, including recently the likes of Joan Didion and Joyce Carol Oates, have found solace in exploring that pain, but Ethel shakes her head. It may bring resolution for some, “but not for me. Rose Kennedy said that after a storm, the birds still sing. You just get on with it.”

“People focus on the dark things,” Rory says, pointing out that this interview is trending the same way. “On the tragedy. But there were more happy times than sad, and that was one of the reasons I wanted to make the film, to show that.”

She is right, of course. For many Americans the deaths of the Kennedy brothers were so personally painful, the loss so profound that the men and their families became, almost instantly, the stuff of myth, symbols of what might have been and was not. That is, after all, the essence of tragedy.

And tragedy does seem to haunt the Kennedys; Ethel lost one son to a drug overdose and another to a skiing accident; a daughter-in-law recently hanged herself. But the living children of Ethel and Robert Kennedy are all vital, successful people, and here is Ethel at the Beverly Hilton doing press at the behest of HBO. Life does go on, has indeed gone on.

Even so, certain moments remain fixed in time and the people of those moments remain fixed as well. The living evoke the dead and the memory of what those deaths meant. That too must be a burden, for Ethel Kennedy and her children, to see in other people the endless permutations of love and grief, and the need for them to see it. .

I wanted to tell this lovely woman who has seen so much about my father, how he wept in a way I never saw him weep again the day her husband died. How he spoke of him often and with infectious admiration. But I did not. At 84, she helped her daughter make this movie and that should be enough.

I closed my notebook, thanked her and Rory, walked out of the hotel and took the elevator to the parking garage roof and got into my car.

Then I took off my glasses, put my head in my hands and cried.

Because my parents are gone now too — and I couldn’t tell them that I had just met Ethel Kennedy.

PHOTOS, VIDEOS & MORE:

Timeline: Emmy winners through the years

Celebrity meltdowns

VIDEO: Watch the latest fall TV trailers here

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.