Grammy Awards 2016: Kendrick Lamar made history with an unapologetically black album

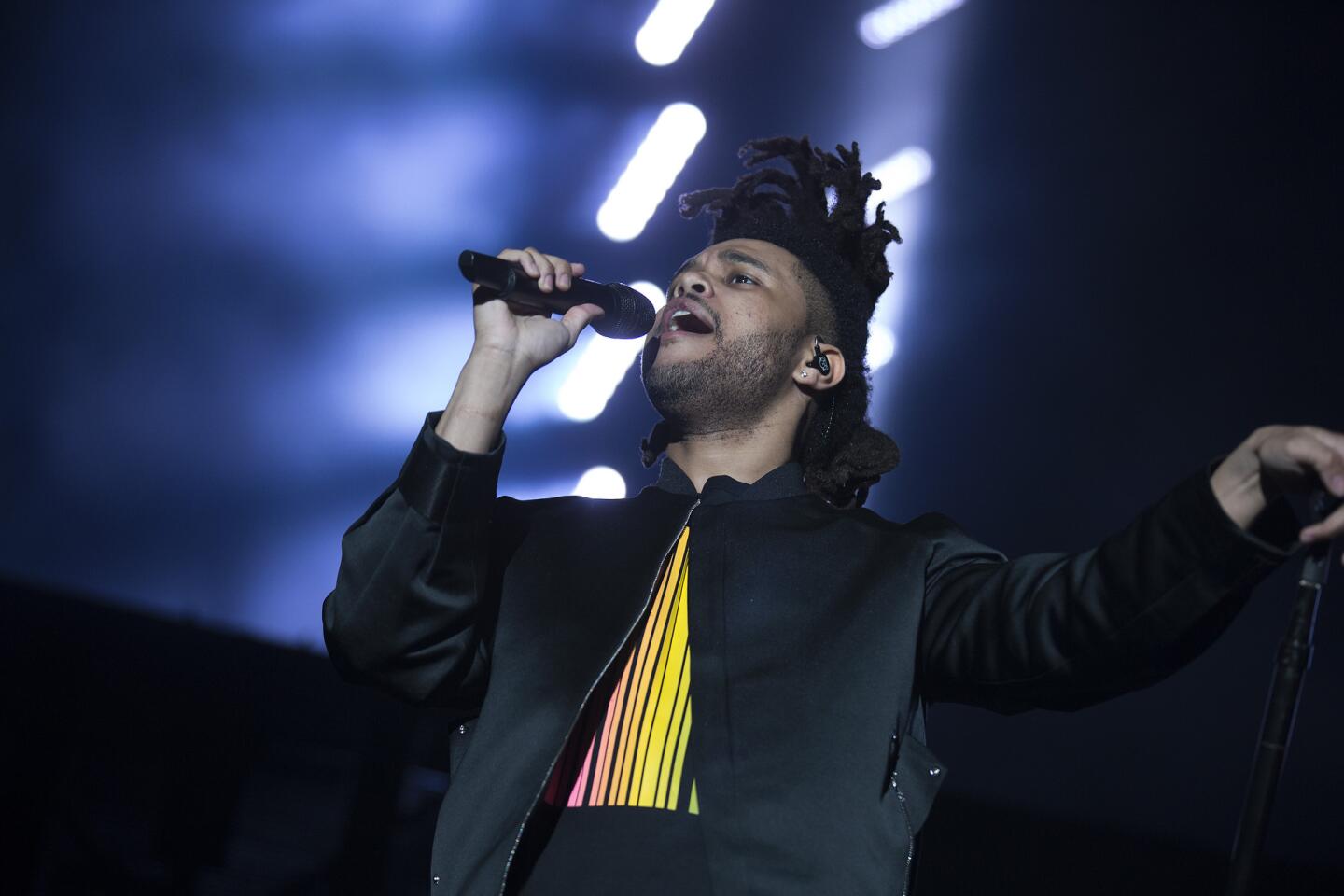

Kendrick Lamar is shown in November at “Kunta’s Groove Session” tour at the Wiltern Theatre.

- Share via

At the 56th Grammy Awards last year, the narrative surrounding Kendrick Lamar was nothing short of front-runner status.

His genre-defining debut “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” which topped countless best-of lists and was deemed a rap classic, was seen as a lock for multiple hip-hop categories and a dark horse for the night’s biggest honor, album of the year.

But Lamar went home empty-handed, eclipsed in rap categories by pop-minded Seattle hip-hop outliers Macklemore & Ryan Lewis.

FULL COVERAGE: Grammy Awards | Complete list of nominees

However, less than two years after that controversial snub, the Compton-born emcee has made Grammy history. Earning 11 nominations — including two in the major races, album and song of the year — Lamar is the most-nominated artist heading into February’s ceremony.

Further solidifying his status as a leader in a new generation of hip-hop wordsmiths, he unseated Eminem to become the rapper with the most nominations in a single night. (Michael Jackson, with his 12 nods in 1984, still holds the all-time record.)

Lamar’s achievement is all the more impressive because he did so with “To Pimp a Butterfly,” a rap album so challenging and musically complex that fans and critics are still chewing on it nearly nine months after its release.

While “good kid, m.A.A.d city” was a brilliant concept record that traced Lamar’s coming of age in gang-and-drug infested Compton, much of it conformed to the mores of a classic hip-hop album (beats that flipped from atmospheric to bouncy, masterfully poetic lyrics, ace guest collaborations). “To Pimp a Butterfly” ignored much of a traditional framework.

Weaving together free jazz, Parliament-Funkadelic era funk, spoken word, slam poetry and live instrumentation and lyrics that looked inward and outward at issues like fame and depression, politics, race, class and beyond.

These ideas aren’t entirely new — hip-hop burst with neo-soul influence in the ’90s (see the Roots, Slum Village, Common) as well as in jazz-minded alternative hip-hop with Afrocentric ideologies heard in the Jungle Brothers, A Tribe Called Quest, Digable Planets and De La Soul.

Unlike his peers in mainstream rap — records by J. Cole, Nicki Minaj, Drake and Dr. Dre will compete with him in the rap album category — Lamar’s latest is a difficult listen that requires multiple listens in order to digest.

The ideas are tough, the lyrics as fiery as they are deeply complex and the instrumentation is heavy and often scattered. The album is far more challenging than anything on radio — or any rap album among this year’s nomination class — but it’s also far more interesting than anything out there.

It’s that challenge from Lamar that makes his Grammy bounty all the more impactful.

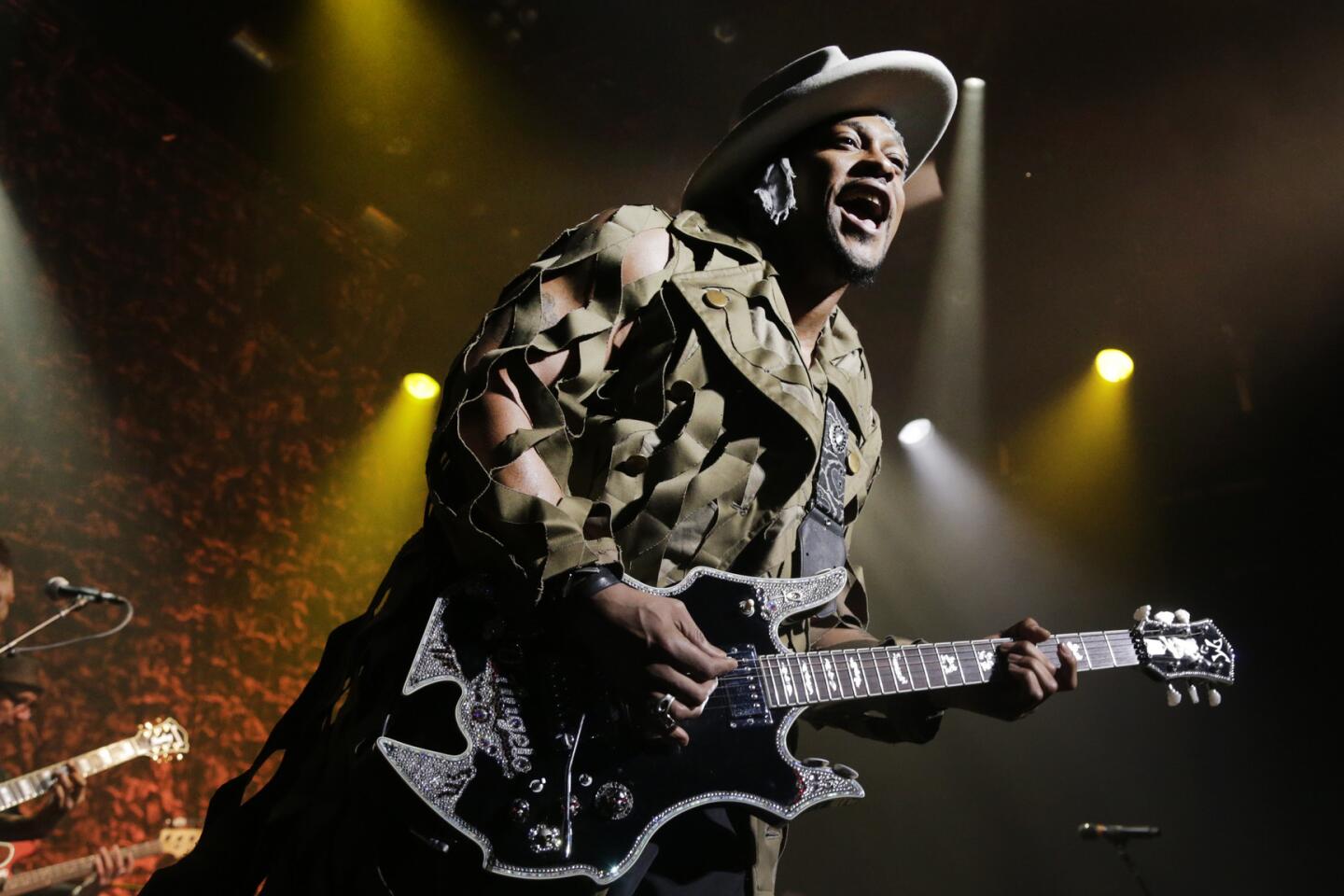

As the deaths at the hands of law enforcement in Baltimore, Cleveland, Staten Island and elsewhere have reignited the ongoing debate over the use of lethal force disproportionally against blacks by law enforcement, Lamar’s album — much like that of D’Angelo’s muscular “Black Messiah” — was unapologetic in its blackness, speaking directly, and exclusively, to a black audience.

In the age of #BlackLivesMatter, Lamar (and D’Angelo, who also landed multiple nods, including record of the year) provided the intense, but necessary soundtrack.

That his empowering, post-depression track “Alright” has emerged as a modern protest anthem for Black Lives Matter protesters should be no surprise with a chorus as optimistic as “We gon’ be alright / Do you hear me, do you feel me? / We gon’ be alright.” (The song is a Grammy contender for song of the year.)

The album’s first single, the euphoric, Isley Brothers-sampling single, “i” (which landed him his Grammy award earlier this year) as well as contrasting companion “u,” deftly explores the struggles of black self-love and the “survivor’s remorse” of making it out of the hood.

Behind the dance-hall bounce of “The Blacker the Berry” lies a raging exploration of the disregard of black life and his own hypocrisy.

“I’m African American / I’m African, black as the moon, heritage of a small village / Pardon my residence / Came from the bottom of mankind / My hair is nappy, my [penis] is big / My nose is rounded wide / You hate me don’t you? / You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture / You’re … evil / I want you to recognize that I’m a proud monkey,” he raps.

Upon its release, the album was instantly acclaimed. But amid the chorus of praise, came thoughtful discussion on the album’s themes — as well as its intended audience.

A writer for Jezebel waxed about the album’s “overwhelming blackness”; Slate wondered how white listeners should approach the record; the Verge heralded Lamar as “Black America’s poet laureate”; and Fader dubbed the album “emotionally draining” and “critic-proof,” even asking, “How do you assess something that is not addressed to you?”

And just last month hip-hop magazine Complex incited an online fervor among rap fans when it revisited the complexities of the album and asked a very polarizing question: “Why did everyone claim to enjoy Kendrick Lamar’s ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’?”

It’s very likely that this difficulty is what enticed Grammy voters. Next to “i” the album’s other big radio hit was “King Kunta,” which took its name from a rebellious slave in “Roots.” However, that same quality may be the very thing that may scare them away when it comes time to complete their final ballot.

Win or lose, though, Lamar has made rap history, even if the inspiration came from the darker moments in America’s history.

For more music news follow me on Twitter: @gerrickkennedy

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.