Josh Kun explores how Latin American musicians and composers influenced and transformed Hollywood movie music

- Share via

As Los Angeles musician Alberto Lopez told it in a Highland Park cafe last week, his great uncle’s name was Juan and he was an influential jazz arranger best known for his work starting in the 1930s.

To succeed in the American music business, though, early on he, like many others, felt compelled to make a concession.

“He had to change his name from Juan Manuel Cascales to Johnny Richards to be able to work,” Lopez said, listing his uncle’s accomplishments with such jazz legends as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Max Roach.

Beginning Saturday evening and lasting through December, a musical series as part of the ambitious Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA — an exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles — will aim to highlight the cross-border contributions that too often have gone unheralded in this city’s musical history.

It’s part of an increased effort by Pacific Standard Time to include music programming, which in this installment will range from contemporary Latin pop and avant-rock to film music.

Richards’ nephew Lopez, a producer and percussionist for the Afro-Latin funk band Jungle Fire, and curator Josh Kun were sitting at Civil Coffee discussing the themes of “The Tide Was Always High: Musical Interventions,” a six-event series that commences Saturday at the Getty Center.

The “Musical Interventions” series is programmed by author, USC professor and MacArthur fellow Kun.

Saturday’s inaugural performance, “Sonorama!,” focuses on the largely untold history Latin American film composers in Hollywood such as Richards, Juan García Esquivel, Lalo Schifrin and Maria Grever.

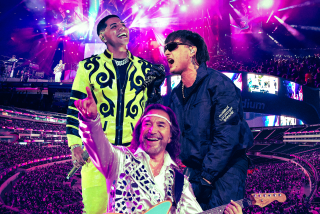

The event will feature the Mexico City producer Mexican Institute of Sound (Camilo Lara) and a collaboration between Lopez and Tucson-based bandleader Sergio Mendoza, with Kun offering between-set context.

Kun, whose research and writing has emphasized cultural exchange and assimilation in border regions, said he wasn’t familiar with the Richards story until Lopez told him.

Kun promptly started buying Richards’ albums and noticed a pattern in the liner notes: most presented the musician as an Anglo arranger. At the same time, said Kun, “They would all talk about his unique skill for Latin arrangements — but as a white arranger — and not talk about his past or his identity.”

Lopez described his uncle, who worked on a lot of film scores, as “very progressive not only in harmonics, but he didn’t care what color you were or where you were from. Because — look at him — he had to change his name to work.”

The tension that drove “Juan” to become “Johnny” also moved another of Lopez’s uncles, the late Bing Crosby bassist Jose Cascales, to work as Joe.

When Lopez’s bandleader-grandfather was preparing to make his debut on CBS and the producers asked Carlos Guillermo Cascale what his stage name was, they balked, said Lopez. “From now on you’re Chuck Cabot and his orchestra. He stayed Chuck Cabot until he was 93 years old.”

Such whitewashing serves to diminish the contributions of generations of Latino musicians working both in the Hollywood film business and the region’s pop music business.

As a consequence, Kun writes in the introduction to the series’ companion book, “The Tide Was Always High: The Music of Latin America in Los Angeles” (University of California Press), a central truth of the city’s music history remains hidden: Los Angeles was not only “shaped by immigrant musicians and migrating, cross-border musical cultures,” but those communities “have been active participants in the making of the city’s modern aesthetics and modern industries.”

Kun says that when the PST call for proposals came, rather than an object-based art show, he pitched something more ephemeral: What if he gathered a team of academics, musicians and writers to explore the ideas and then, “based on that research, instead of a show we did concerts, or musical events, or musical happenings that tried to bring that research to life onstage?”

His pitch served a few needs. For all its success, the inaugural 2011-12 Pacific Standard Time was notably lacking in music-related events. As well, it allowed him the opportunity to move from the page to the stage to manifest his ideas.

Future programs in Kun’s series, which extends through December, include celebrations of the Peruvian American singer Yma Sumac and the Brazil-Los Angeles musical axis; a sound sculpture at Huntington Gardens by acclaimed sonic architect Guillermo Galindo; and new work by Los Angeles rock band Chicano Batman, inspired by the late Mexican American artist Carlos Almaraz.

Another PST: LA/LA music series will take over Walt Disney Concert Hall in October. Called “CDMX: Music from Mexico City,” its six nights of programming will include acclaimed rock band Cafe Tacuba, the band Mexrrissey (which only plays songs by British crooner Morrissey and his band the Smiths) and the Latin Grammy-winning singer and songwriter Natalia Lafourcade.

The composer Antonio Sanchez and band will appear for a live-to-picture performance of his score to the Oscar-winning “Birdman (or the Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)”; and Juan Felipe Waller, whose “Plato Plastic Dialogues” was composed for a percussion quartet playing disposable plastic plates, will premiere a new piece.

It’s a packed schedule, but even it only scratches the surface.

Says Lopez, “Can you imagine disco without the contributions of Latinos — or hip-hop?”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Sonorama! Latin American Composers in Hollywood, featuring Mexican Institute of Sound and Sergio Mendoza & Alberto Lopez (with special guests)

When: 7 p.m. Saturday

Where: Getty Center, museum courtyard

Tickets: Free ( no reservations required)

More information on this and the series: www.pacificstandardtime.org

For tips, records, snapshots and stories on Los Angeles music culture, follow Randall Roberts on Twitter and Instagram: @liledit. Email: [email protected].

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.