Roger Waters comes ready to rumble and hits his mark on closing night of Desert Trip’s first weekend

- Share via

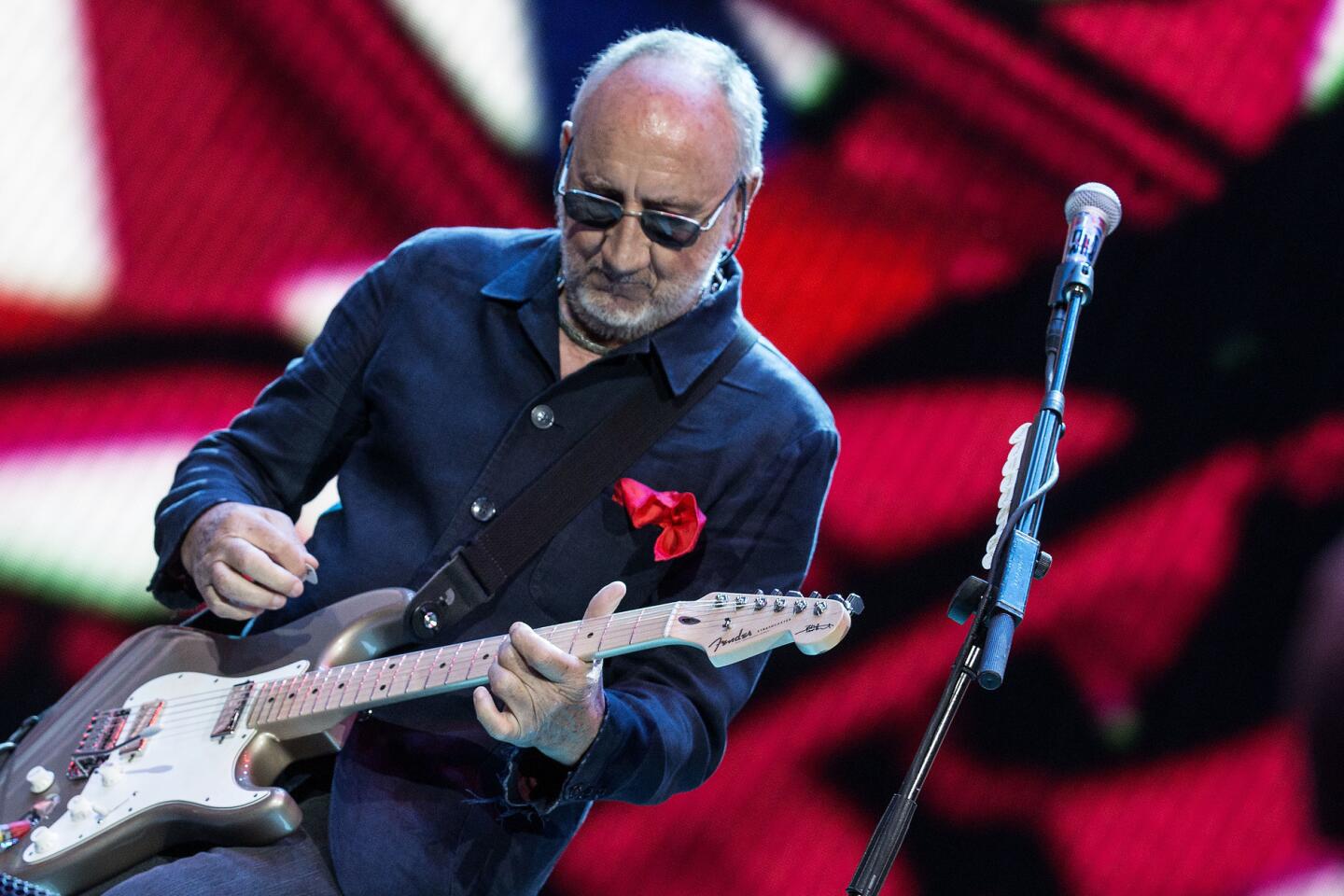

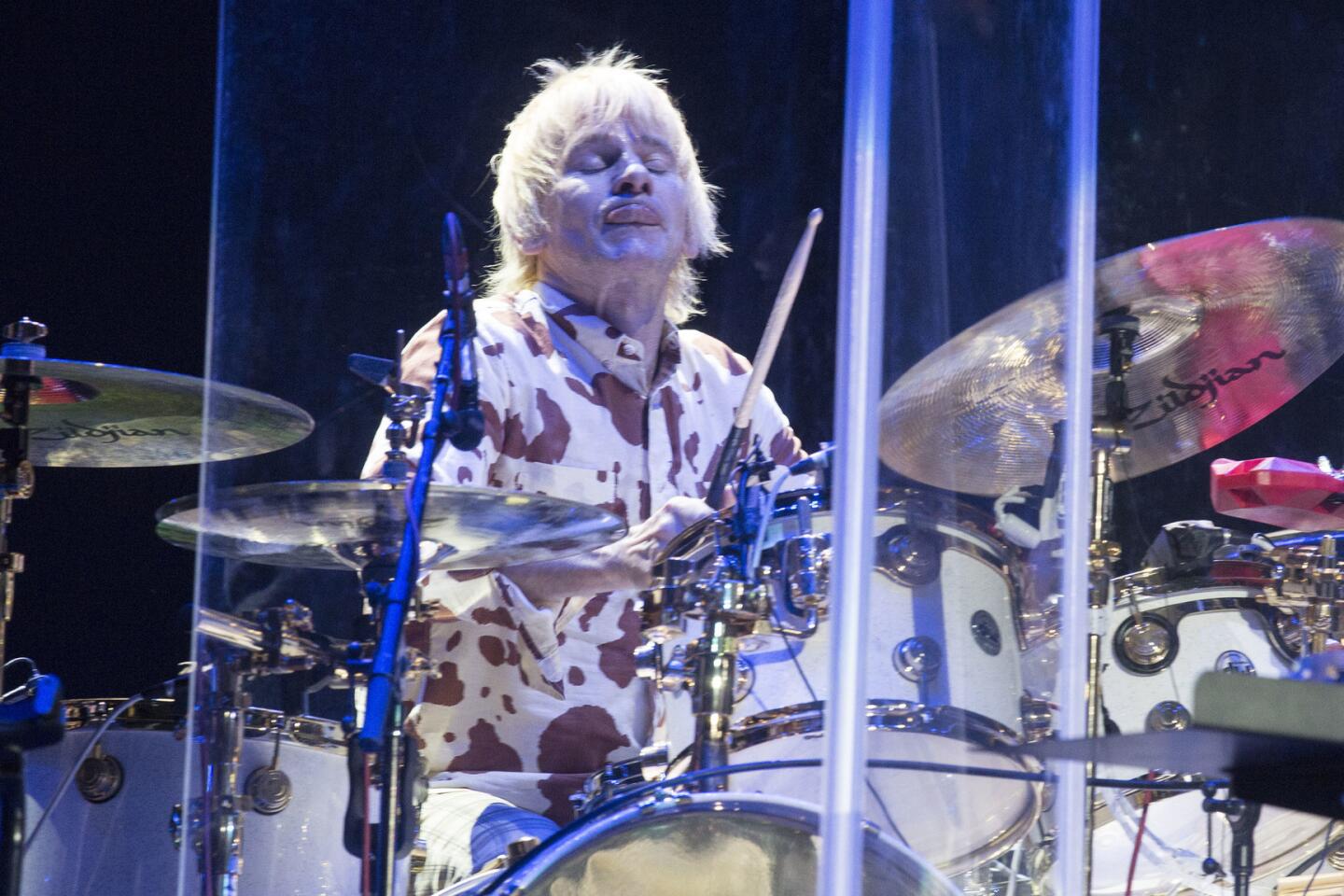

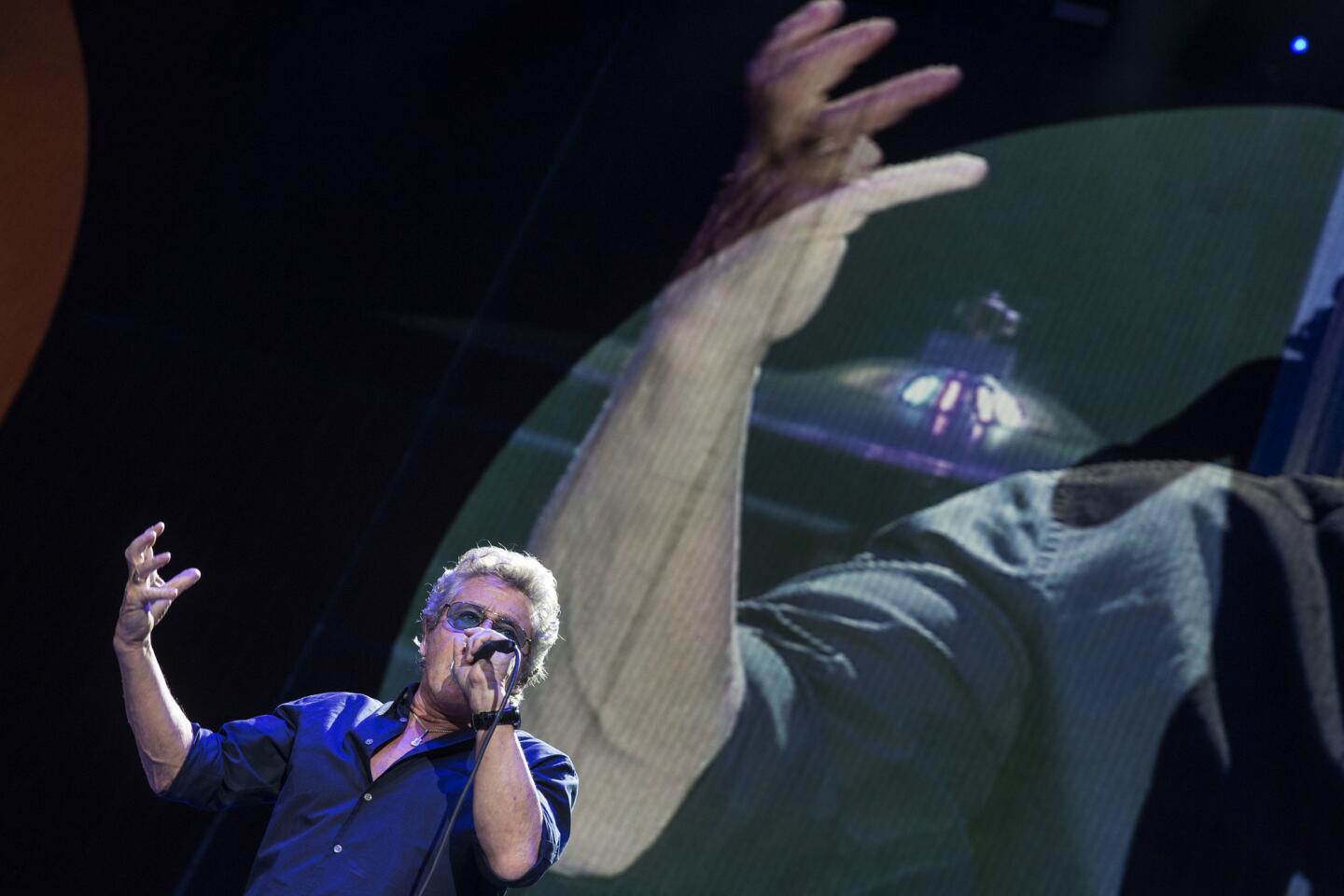

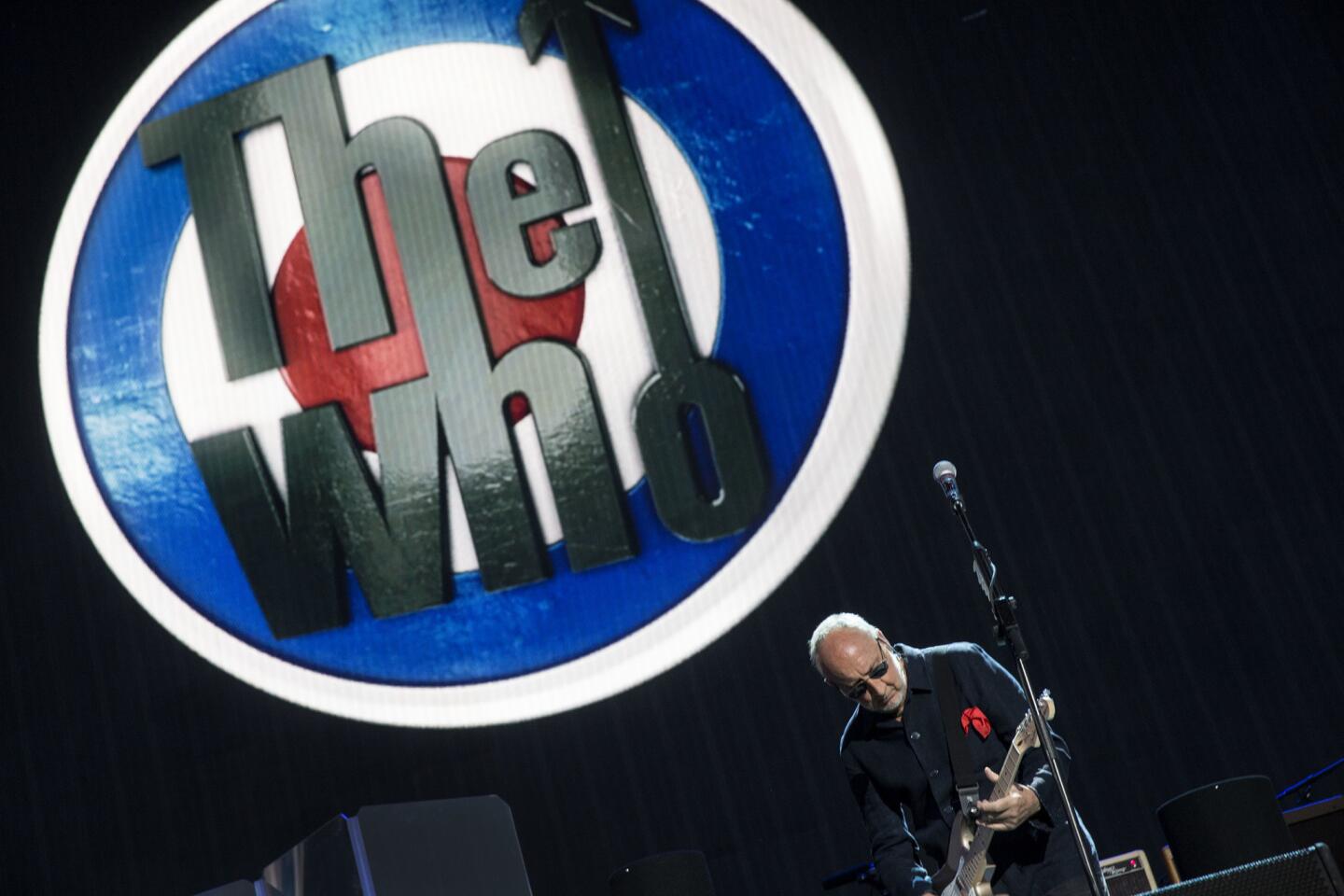

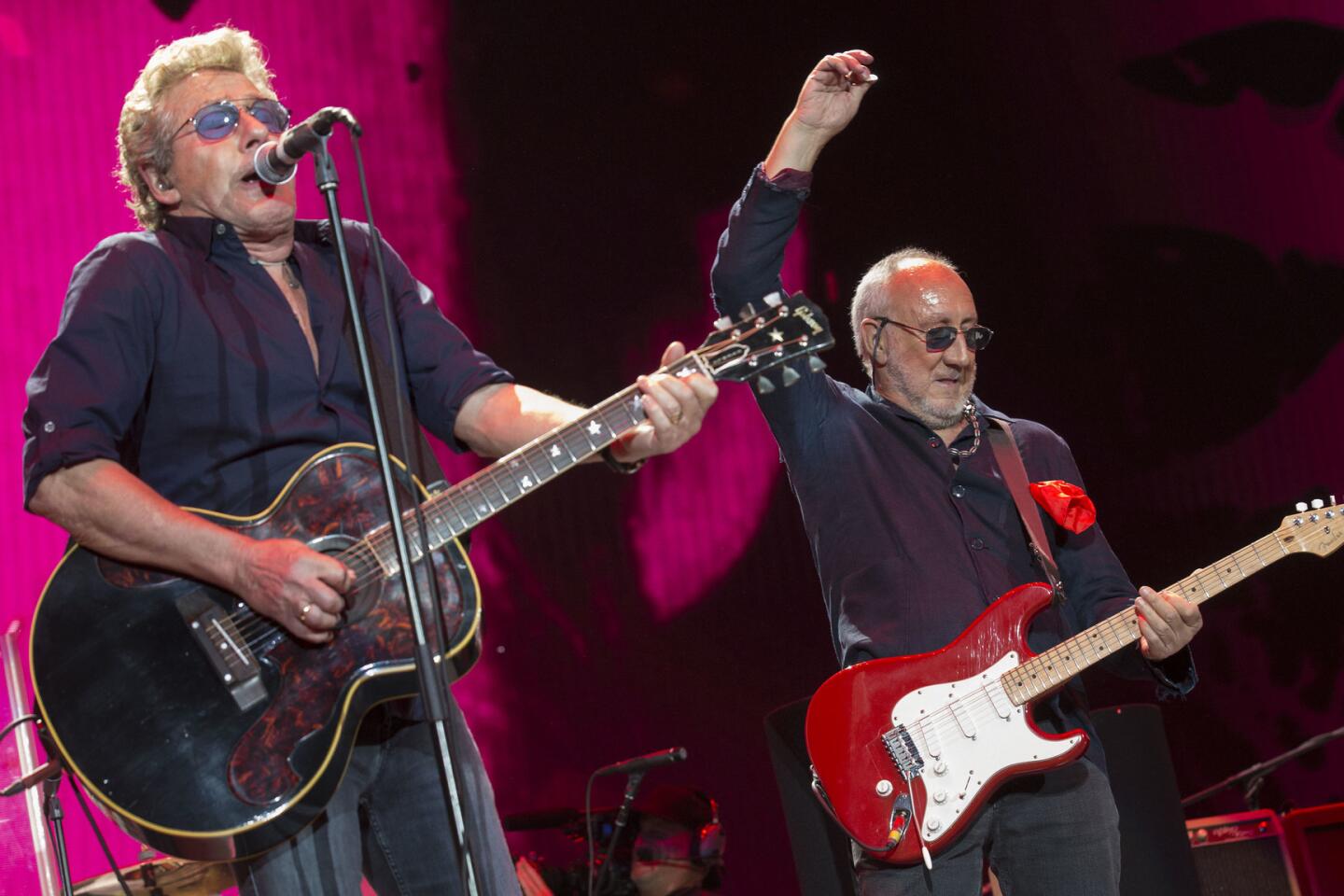

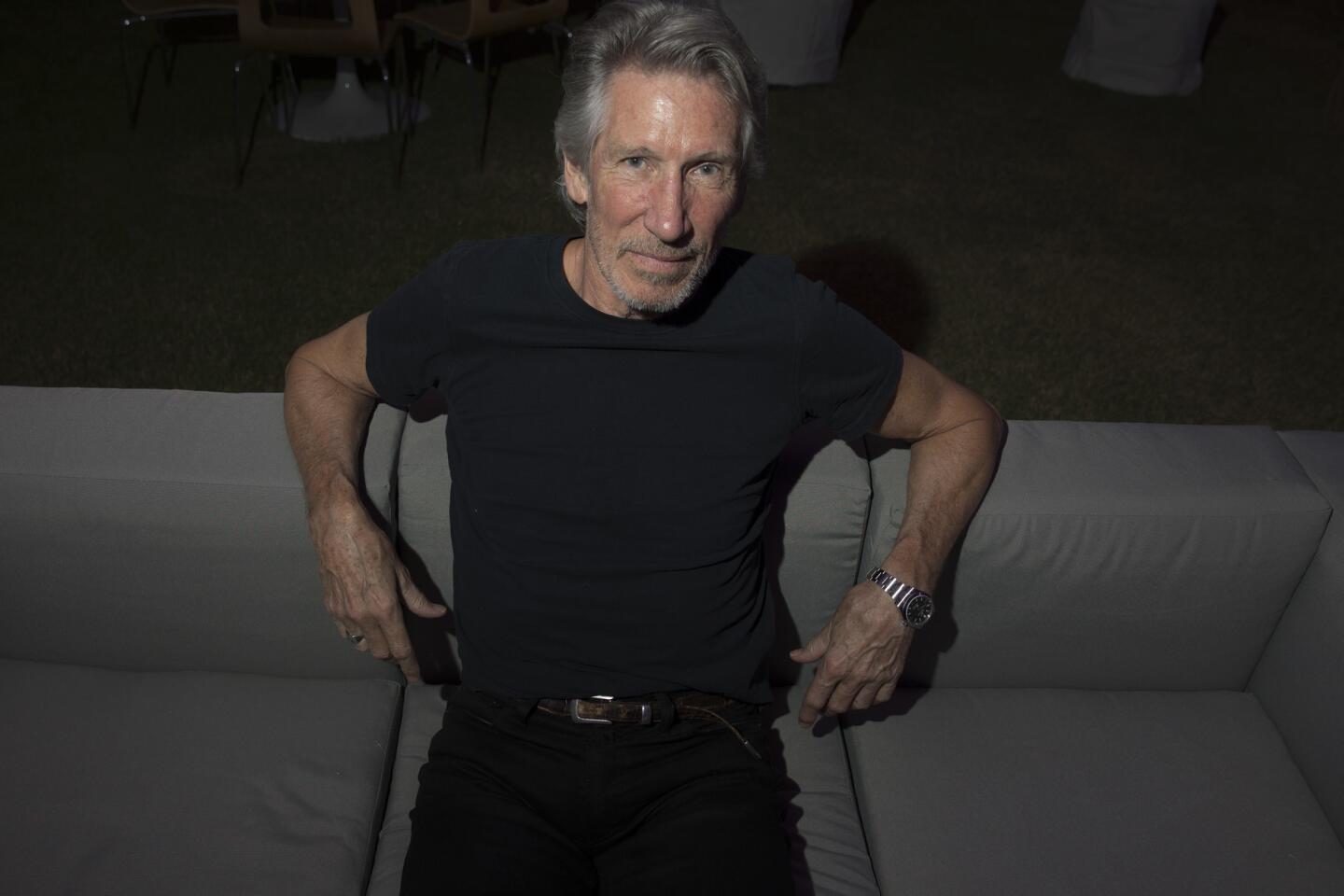

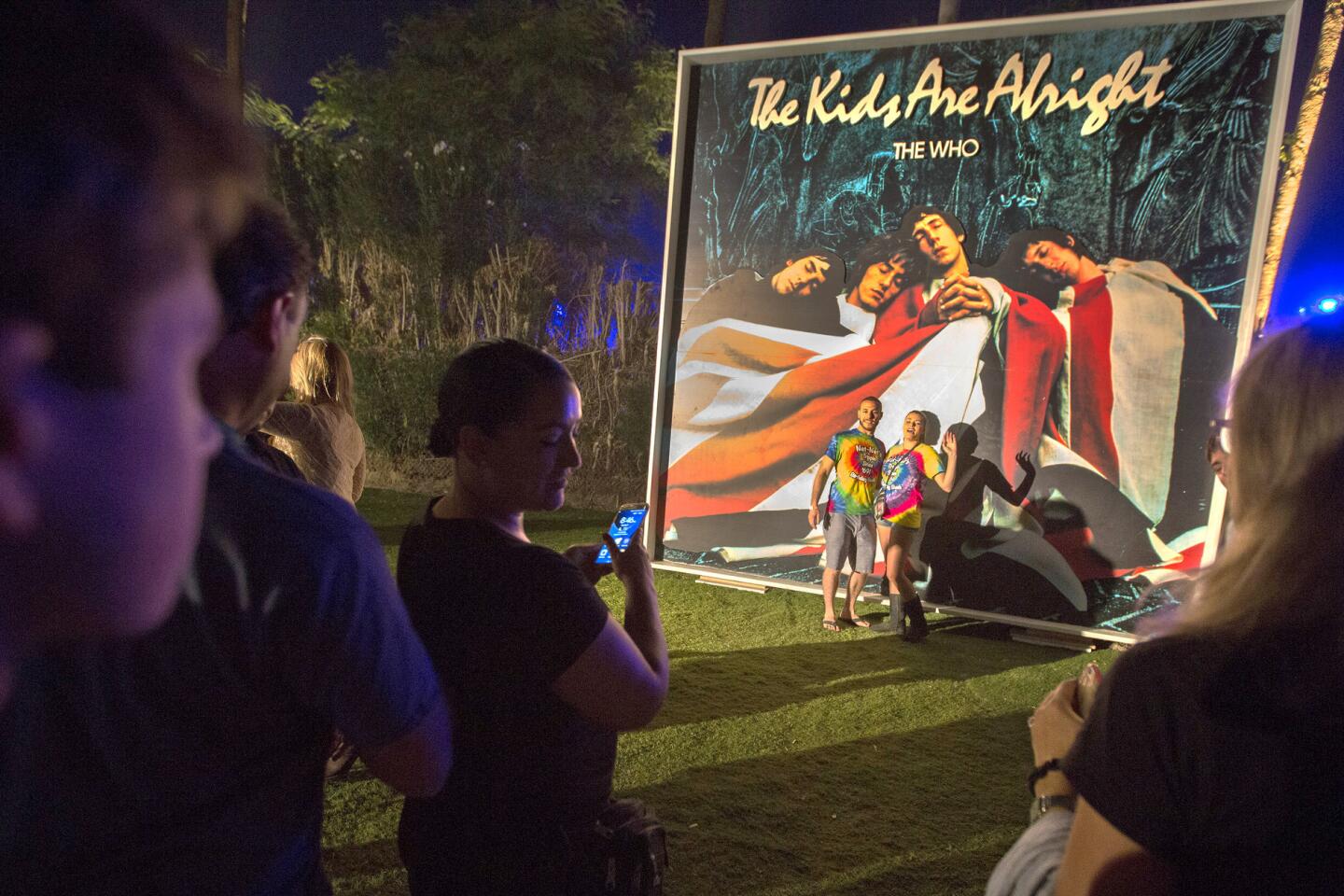

The final portion of the inaugural Desert Trip festival in Indio — and in some respects the event’s piece de resistance — began not with the opening notes of Roger Waters’ concluding set, but the moment after the Who left the stage following their own explosive performance.

During every other break between acts over the weekend — as is the case almost universally at concerts where there is more than one performer— recorded music kicked in over the PA.

For the record:

10:09 a.m. March 5, 2025An earlier version of this post misidentified Nick Mason as Pink Floyd’s keyboardist. Mason was the band’s drummer. In addition, the Pink Floyd track “Speak to Me” was credited to Waters and Mason. It was written solely by Mason.

Not this time. Instead, an eerie silence hung over the expansive Empire Polo Field for nearly an hour. Concertgoers used the time for restroom breaks, to grab another slice of pizza or refresh their beverages at the nearby concession stands, while the stage crews cleared one set of instruments and equipment and installed another.

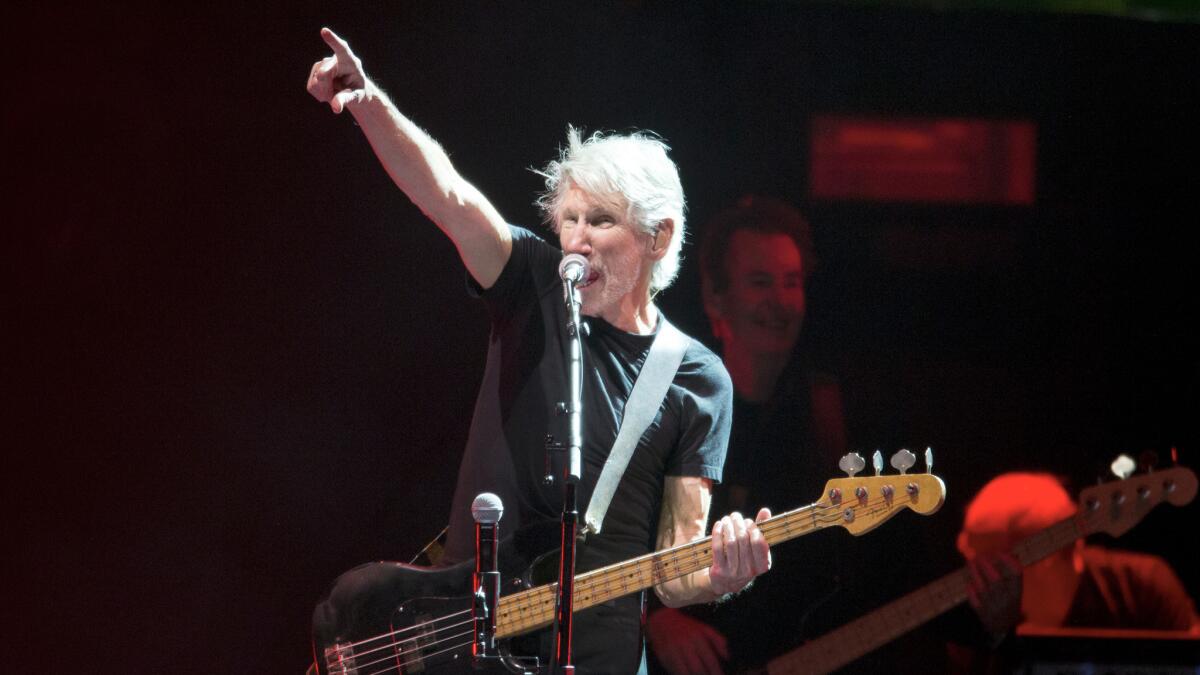

And then the rumble began. What felt like the prelude to a rocket launch at Cape Canaveral rolled over the grounds. Spectators scanned the skies for what they assumed had to be aircraft of some kind passing low overhead.

It turned out to be the work of a high-powered quadraphonic sound system the English rocker had cooked up for this show, one — he had said two days earlier— that would be unique to Desert Trip.

It also was the beginning of an epic production that raised a question few on hand could have imagined at the start: Could it be possible that the vast surroundings, which also play host to the Coachella and Stagecoach music festivals, might not be big enough to contain Waters’ artistic vision?

What transpired gave festival-goers a perfect example of the sense of limitless possibility that define what Waters and Pink Floyd added to the lexicon of rock ’n’ roll, as the genre expanded in the mid- and late ’60s from an expression of youthful rebellion and liberation into a full-fledged art form and platform for Big Ideas.

Waters never met a conceptual challenge he wasn’t ready and willing to surmount. On Sunday he brought a show that incorporated aspects of his recent “The Wall Live” tour and morphed them into another impossible-to-miss assessment of the global state of the union according to Roger.

And yes, pigs still fly. The celebrated floating porker appeared late in the show, the words “Divided We Fall” visible on its side and large Xs over its eyes.

“If You’re Not Angry, You’re Not Paying Attention,” read one of dozens of messages that flashed across the event’s gargantuan triptych video screen behind the stage as Waters and his potent band delved deep into the Pink Floyd repertoire during the 2 1/2-hour set.

Where most of the other performances over the weekend revolved around an artists’ lyrical expressions of thoughts and feelings wedded to melodies, harmonies and rhythms that enhance their ability to penetrate listeners’ heads and hearts, Waters and his fellow art rockers often seemed more interested in employing music as a tool for touring and mapping psychological terrain.

Originally, much of this music provided a soundtrack for head trips, journeys into altered states that often were the product of ingested substances. Now Waters uses the grand stage afforded him to create a sense of shock and awe for concert audiences, a reminder that the experience of live music can provide more than flashy costumes changes, hyperkinetic choreography and blinding pyrotechnics.

He opened with Pink Floyd’s “Speak to Me,” one of several numbers from the group’s 1973 “The Dark Side of the Moon” album. The track, written by drummer Nick Mason, goes a long way toward explaining the mad genius quality that infuses much of Waters’ music: “I’ve been mad for .... years, absolutely years, been over the edge for yonks, been working me buns off for bands.”

From there he proceeded through most of the touchstone numbers of the Floyd catalog: “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” (which he dedicated, as always, to Pink Floyd founding member Syd Barrett), “Wish You Were Here,” “Pigs on the Wing,” “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)” “Money,” “Us and Them” and “Comfortably Numb,” among many others, although serving up hits isn’t what any Waters show is ever primarily about.

His use of the surround-sound system helped achieve a sense of being enveloped in the show, which, as usual for Waters, has much to say about the encroachment of totalitarian forces on personal liberty. Ominous voices, cackles, sirens and other sound effects zoomed around the space between, as well as during, songs.

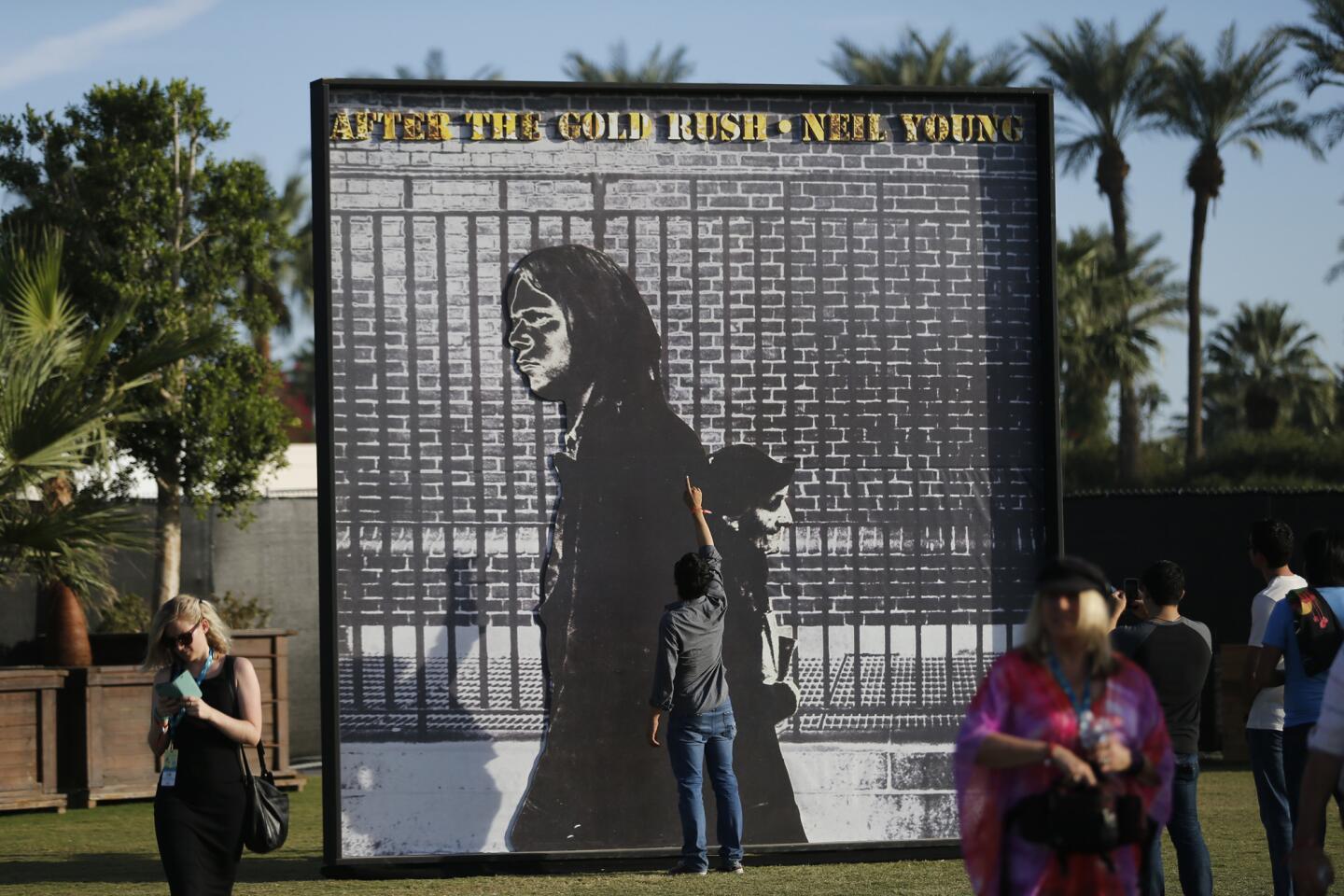

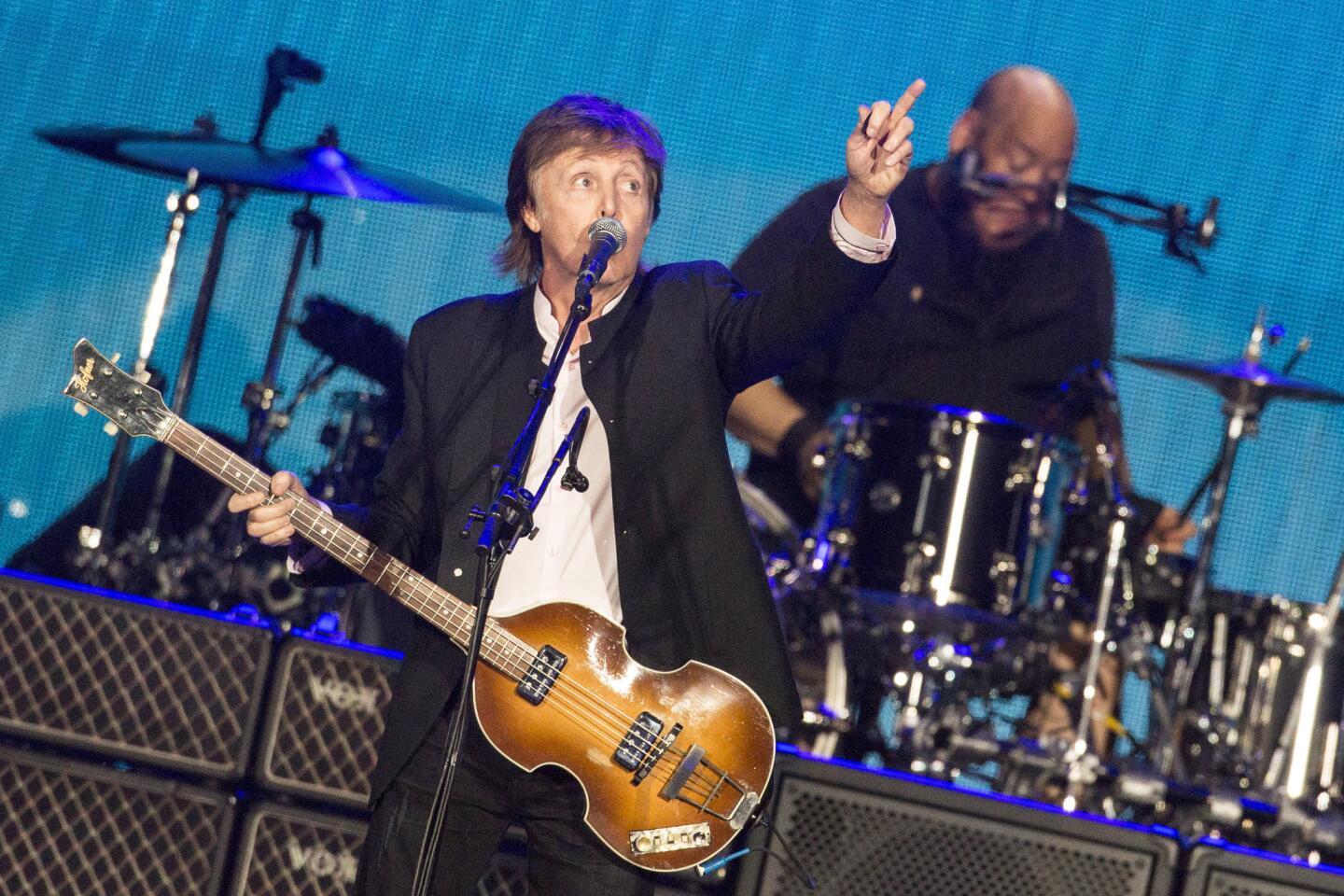

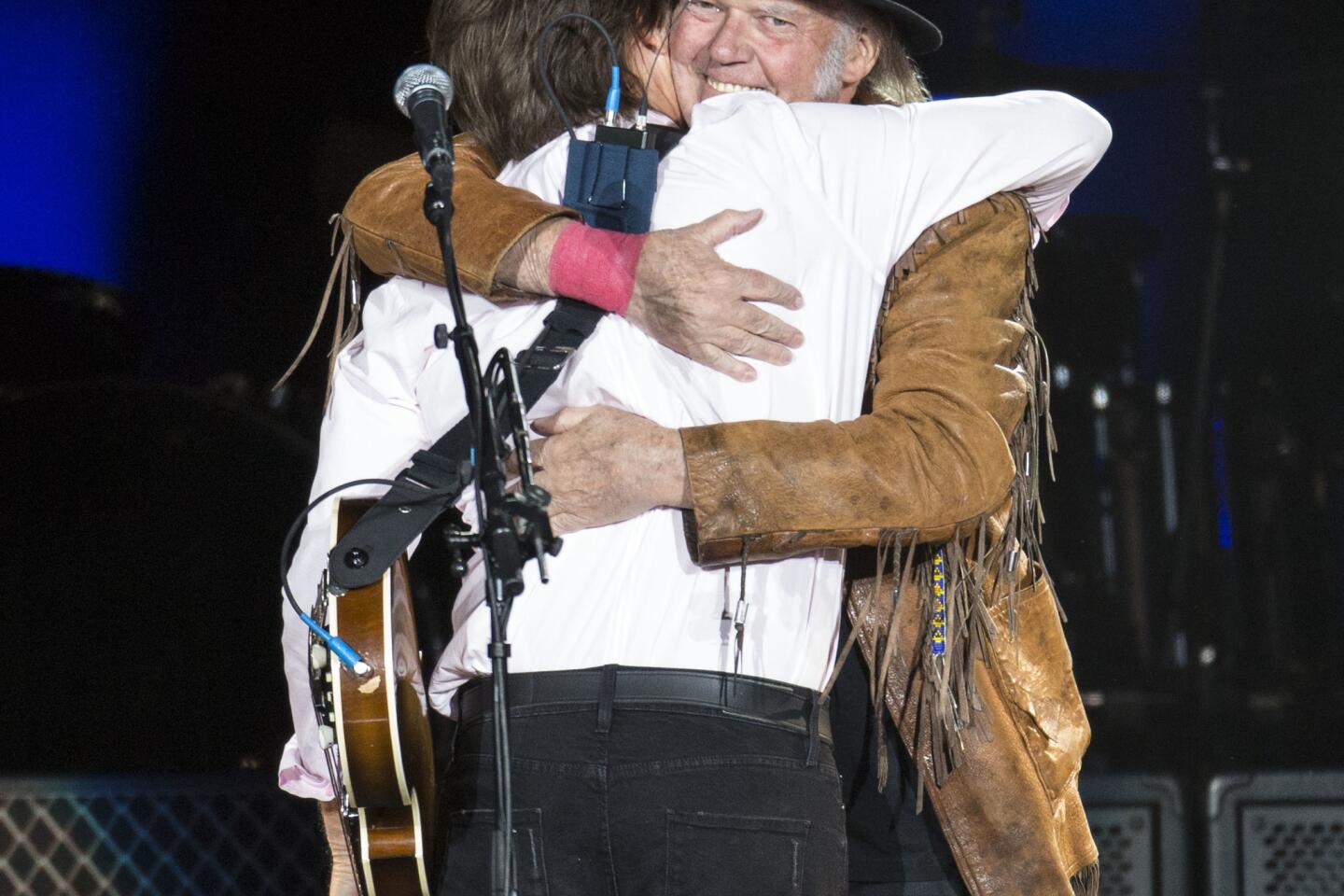

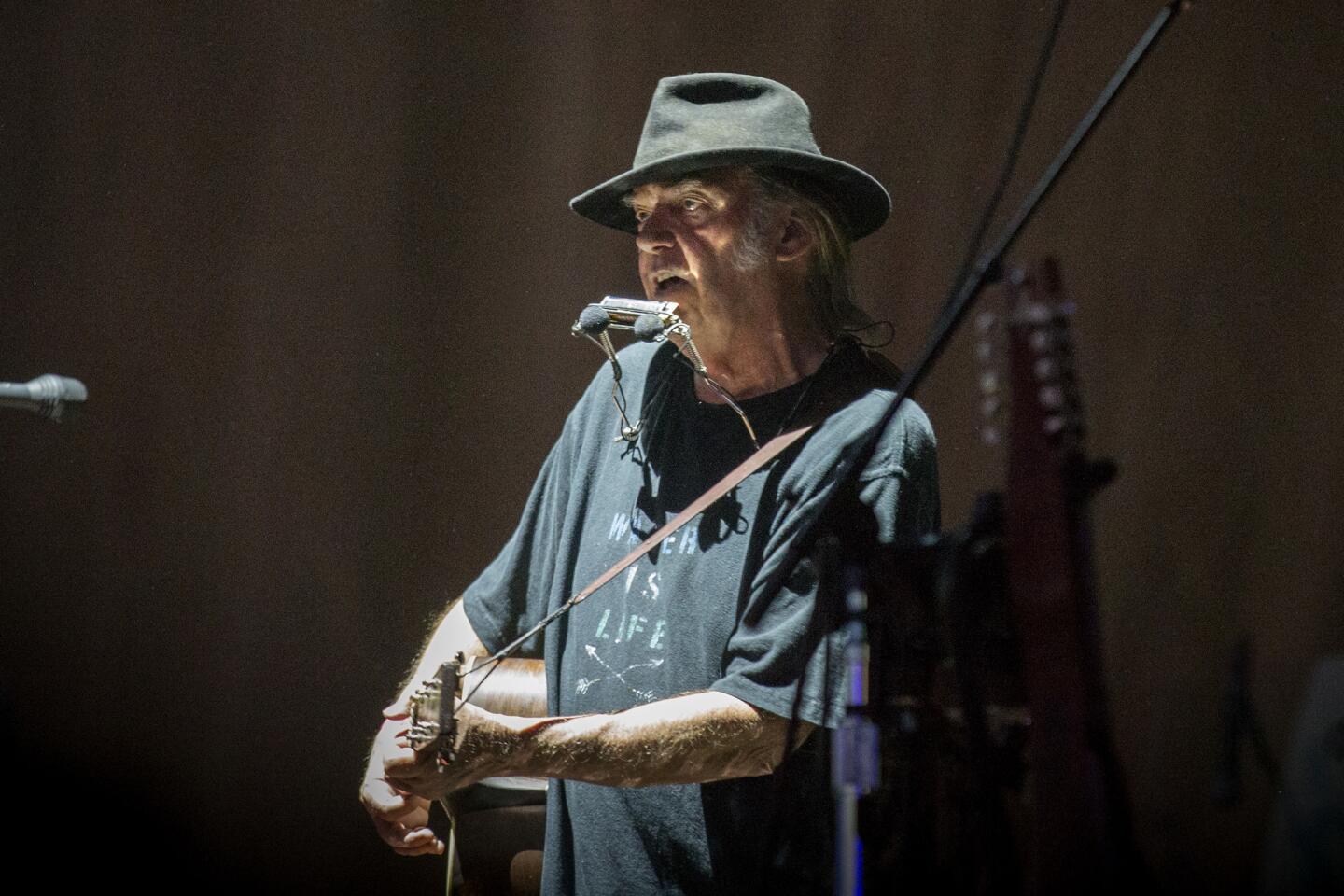

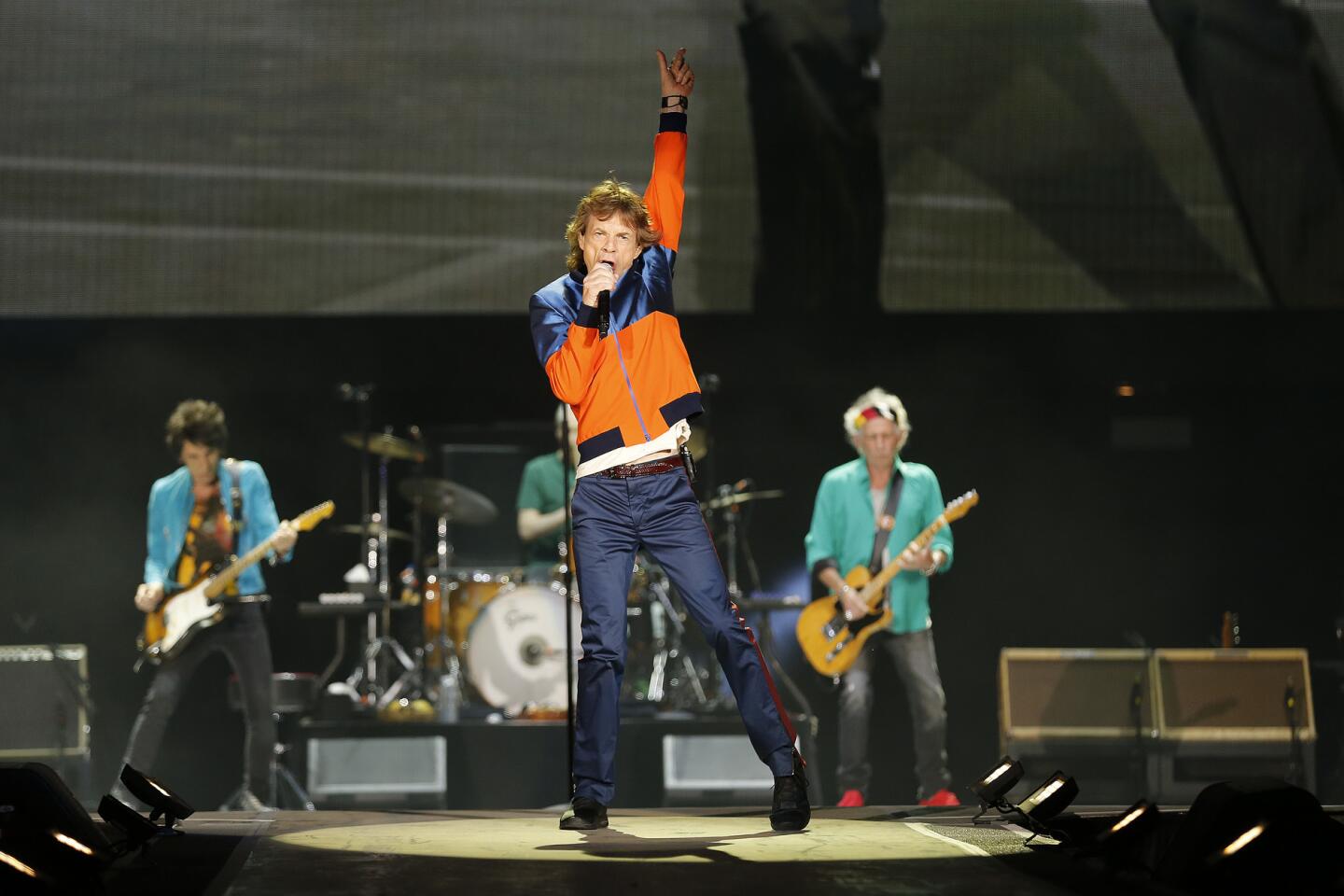

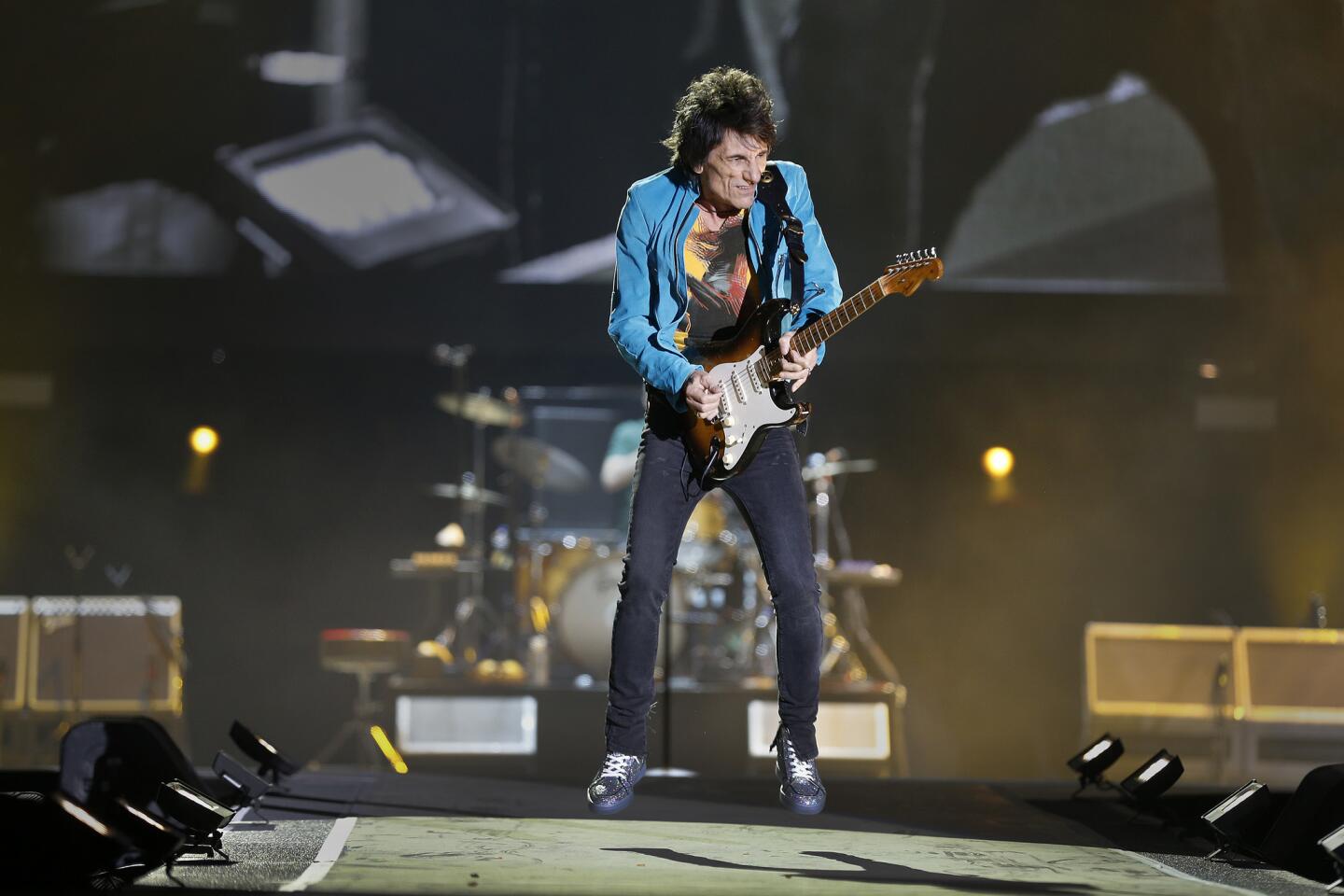

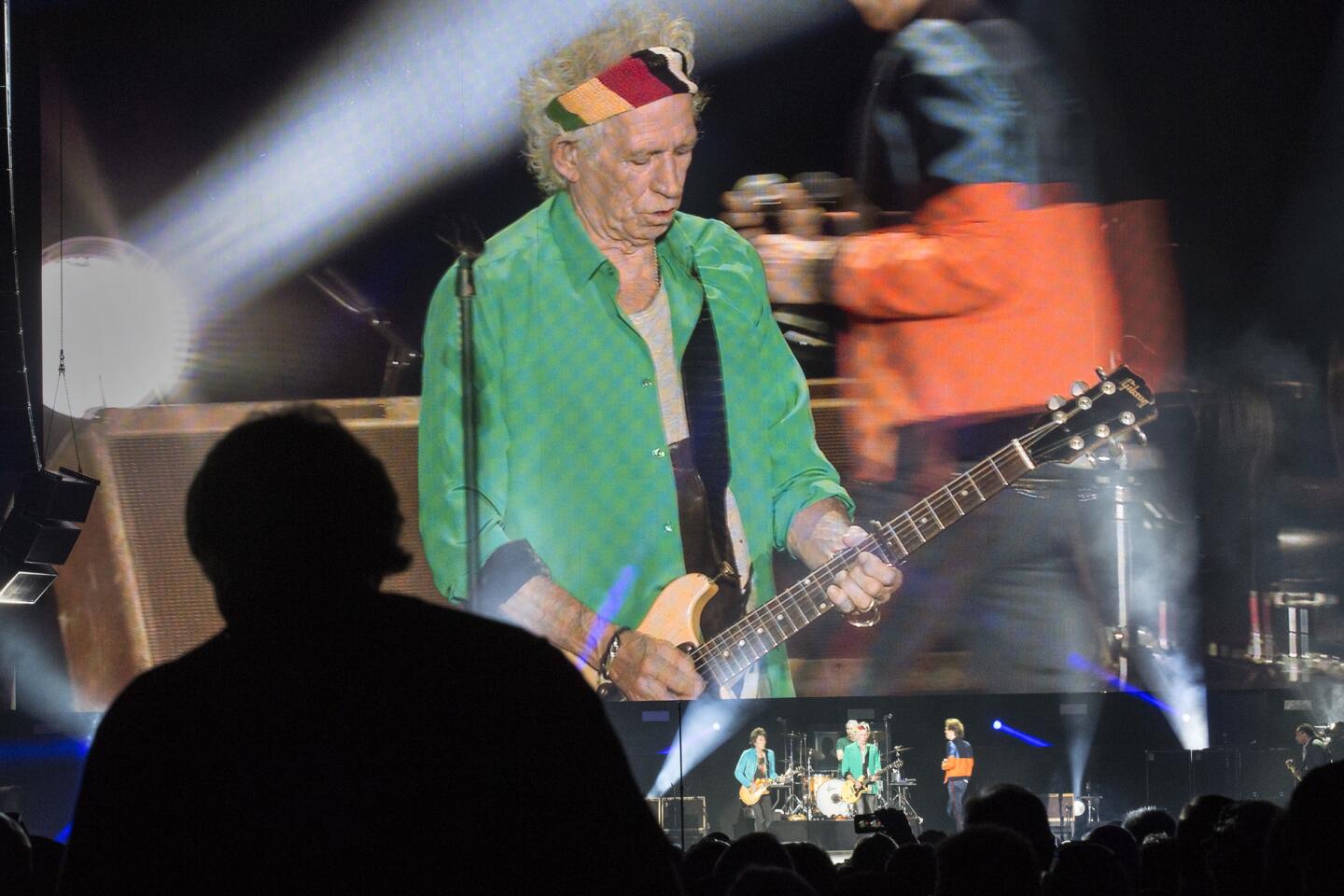

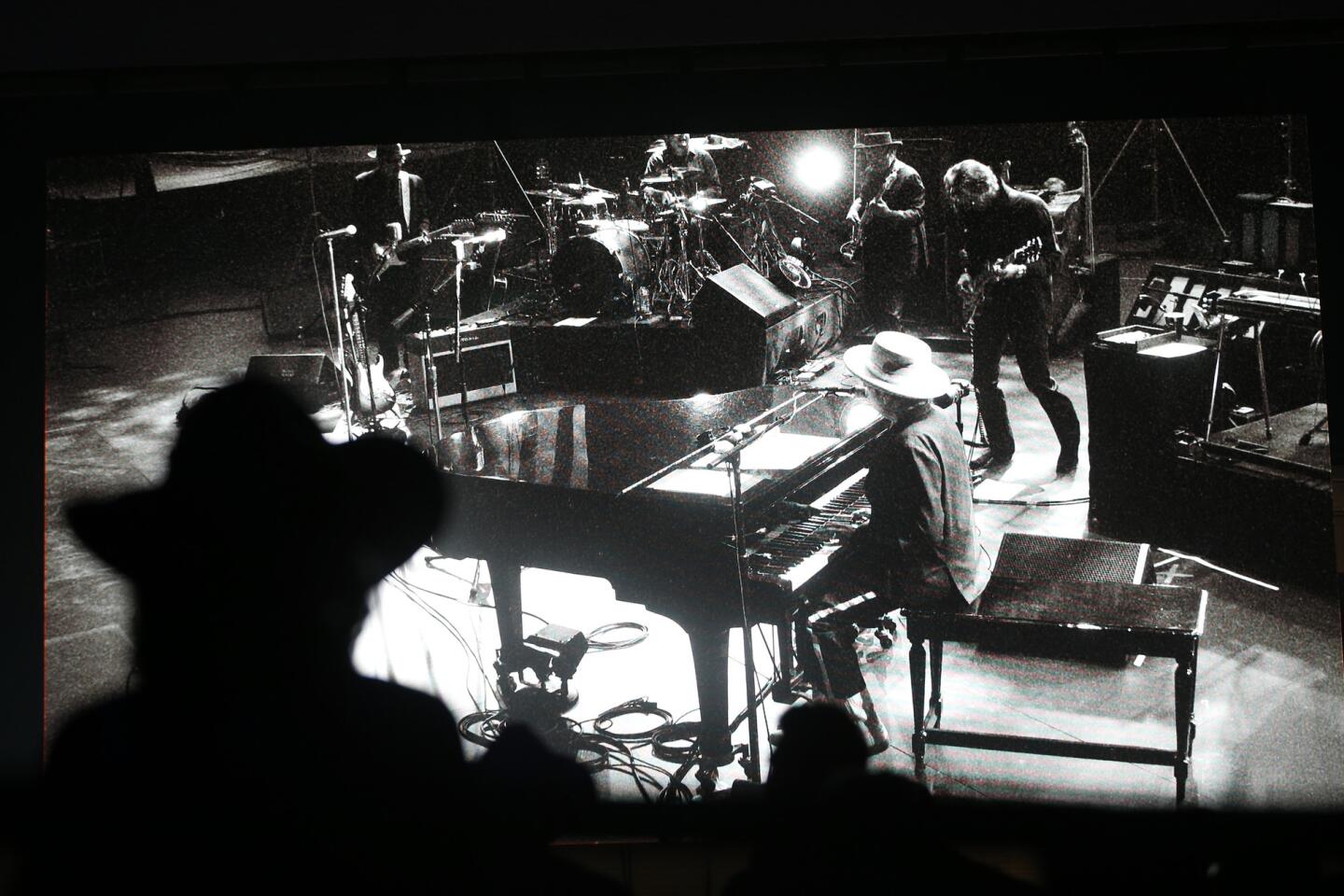

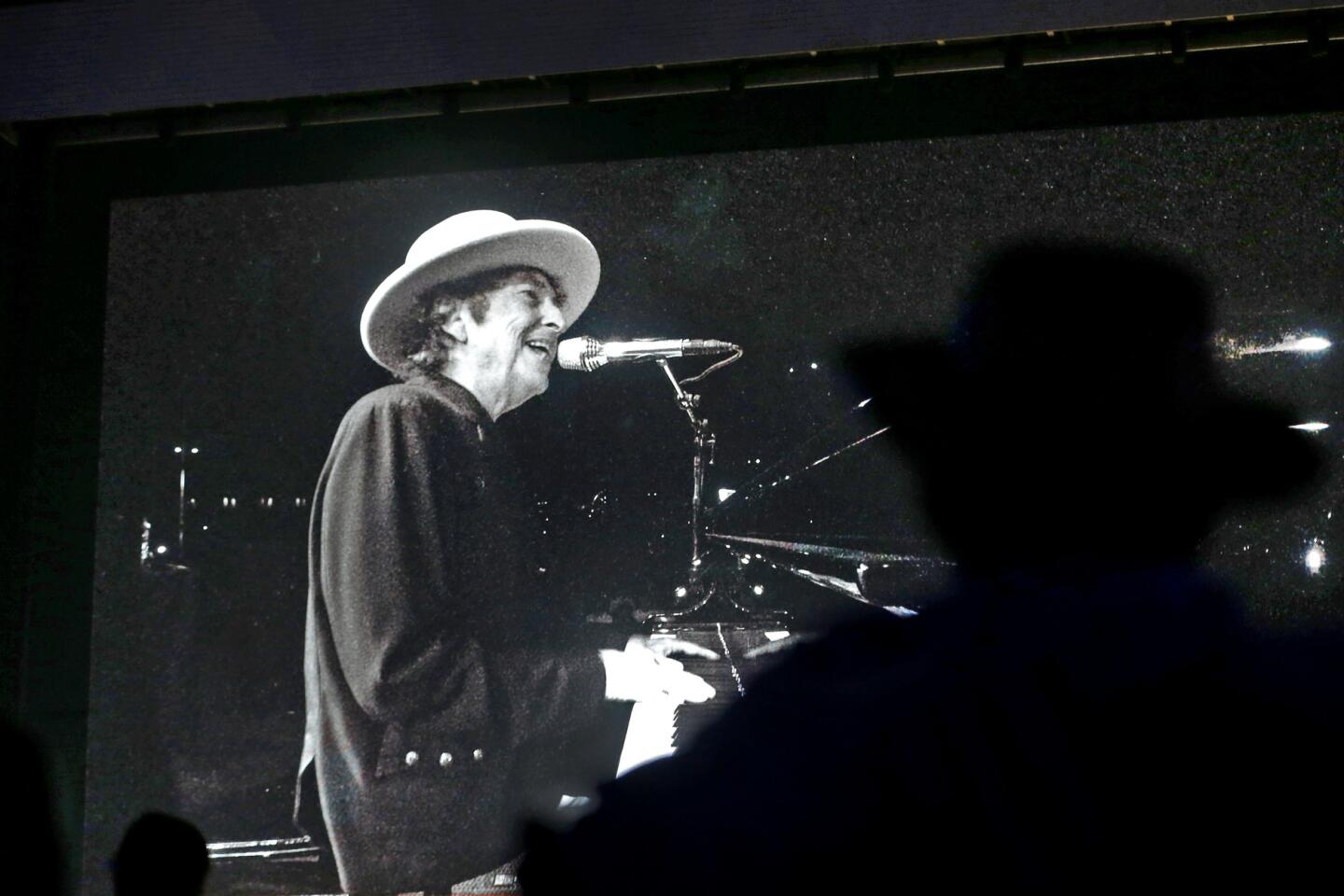

And even though Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Neil Young, Paul McCartney and the Who also used the video screens during their Desert Trip sets, Waters was the one who most fully exploited their sheer size.

He invoked evocative scenes of galactic wonder and imaginative animated sequences and spectacularly magnified faces — his own and those of his band members — and their instruments. You could practically count the grains on the fretboard beneath guitarist G.E. Smith’s fingers in some extreme close-ups.

The big reveal came with the emergence of four massive smokestacks that rose above the video screens, onto which were projected the image of an institutional building of some sort — a prison, perhaps, insane asylum or maybe both.

Near the show’s conclusion, not long after Sunday’s second presidential debate had ended and after the flying pig slowly navigated its way over and around the festival grounds, Waters (who has lived in New York City for the last 15 years) took shots at Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump.

To describe the critique as less-than-subtle is to state the obvious: Waters has always been the kind of rocker to bypass the scalpel if there’s a bludgeon within reach.

It elicited cheers from some and prompted others to head to the parking lot early to avoid the exit crush that many were caught in the previous two nights. He irritated others still on hand further with a quick but pointed reiteration of his pro-Palestinian position on strife in the Middle East, one that’s generated no shortage of hate mail toward him in recent years.

Waters just seems to relish the opportunity to fight back. Mostly he seemed more than happy to finish out the weekend as the artist who put the “trip” in Desert Trip.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.