Talkin’ ‘bout their generation: What Desert Trip says about the classic rock mindset

- Share via

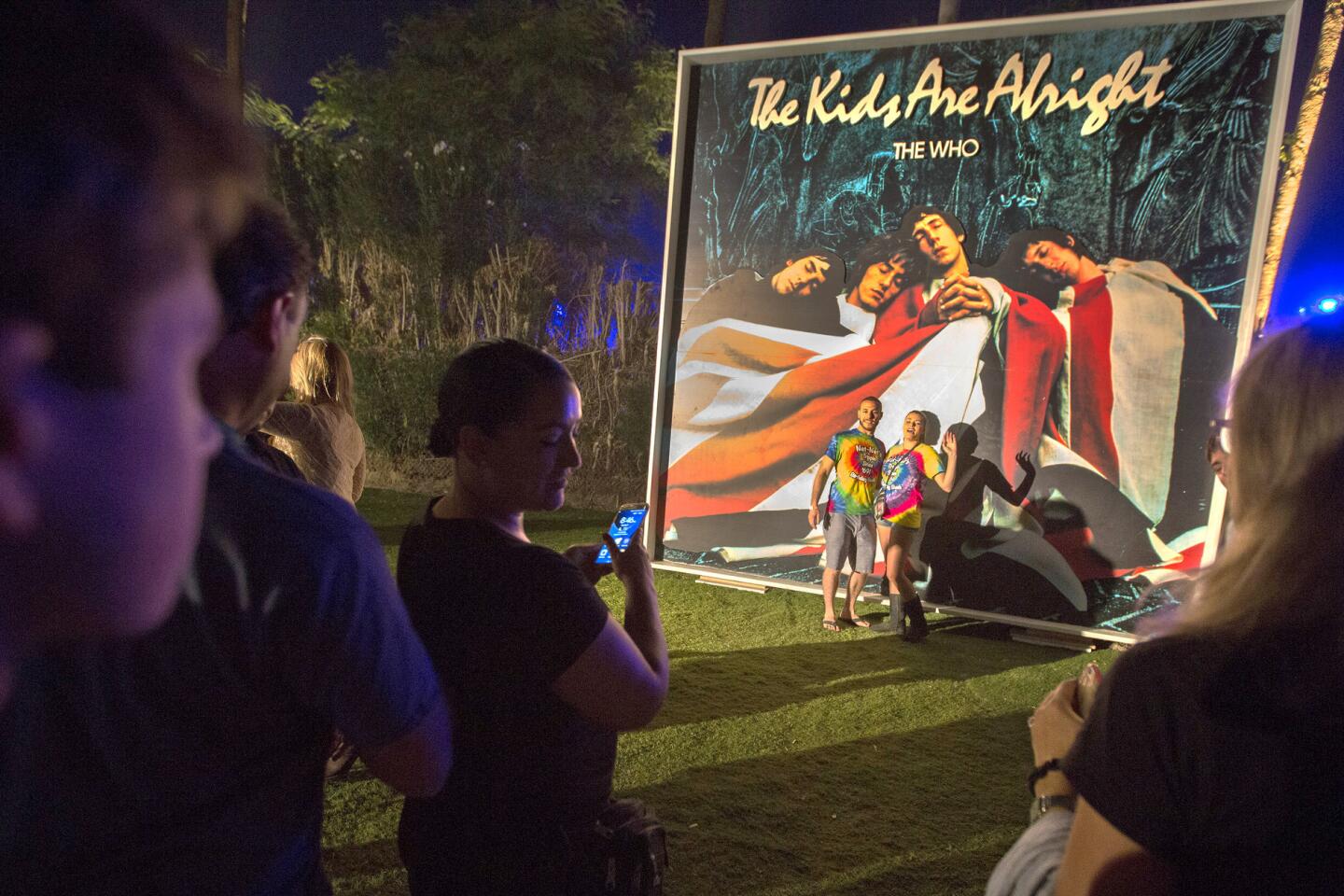

This weekend’s Desert Trip festival has been aggressively marketed as a once-in-a-lifetime event: the first — and presumably last — opportunity to see half a dozen of rock and roll’s formative acts on a single stage.

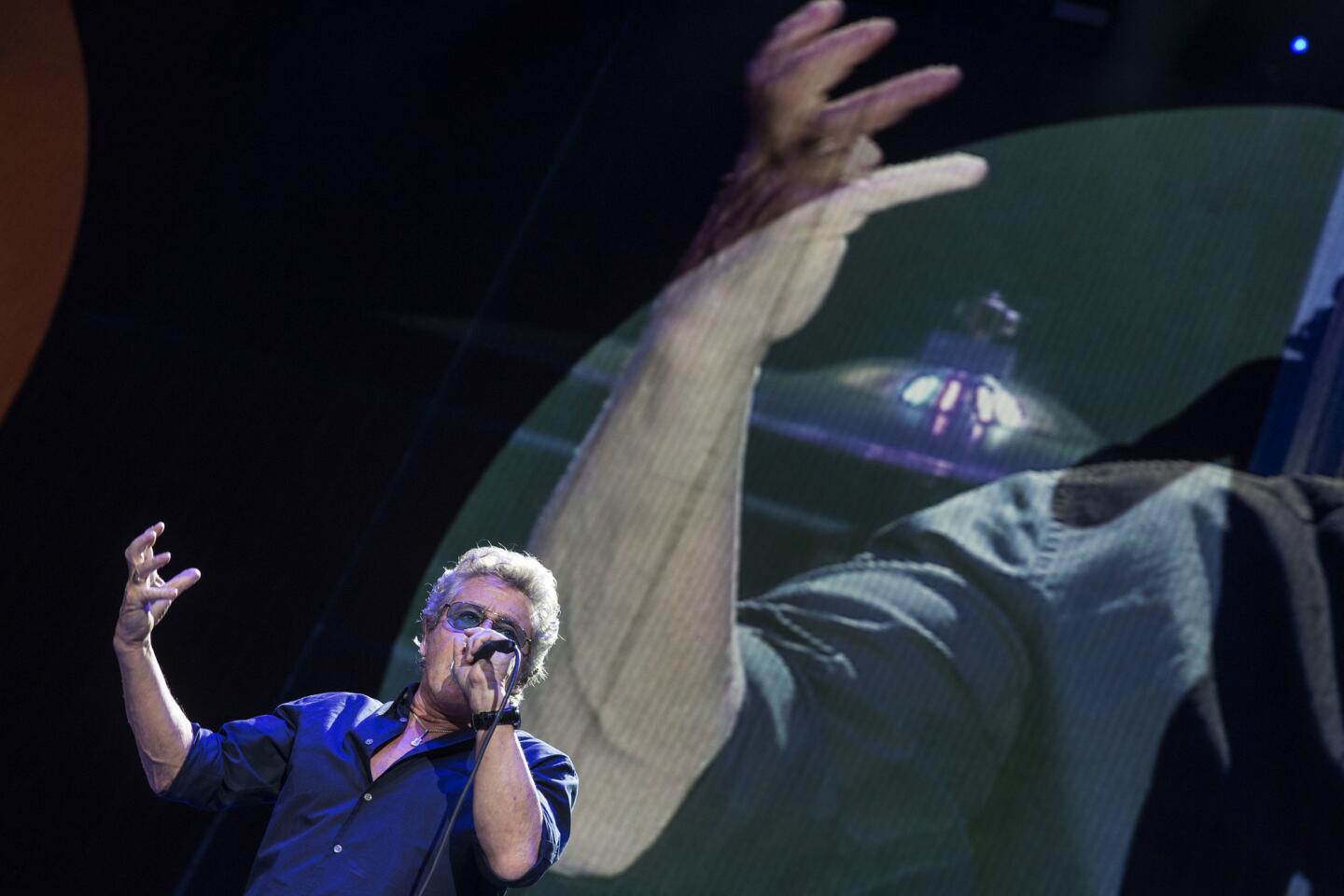

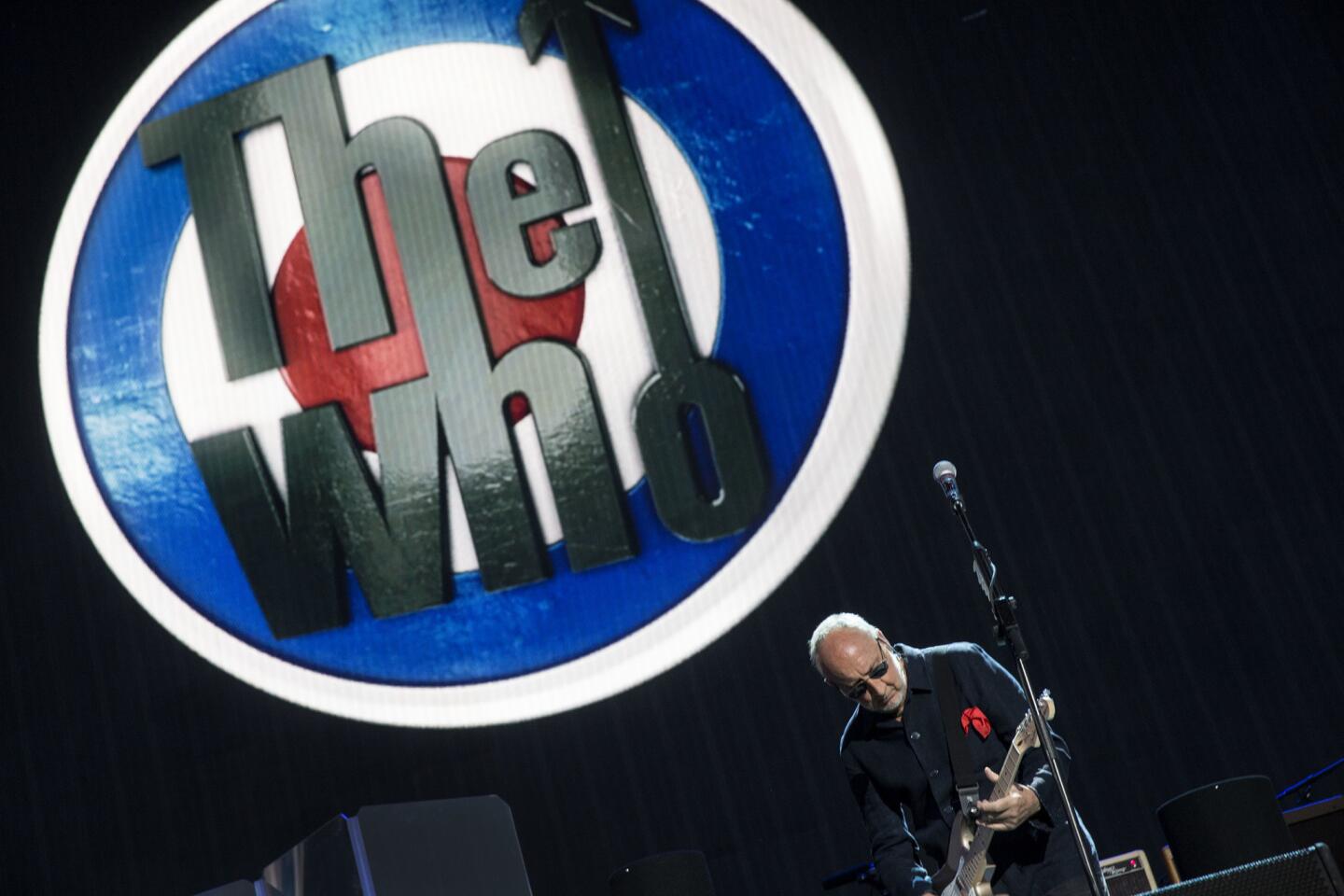

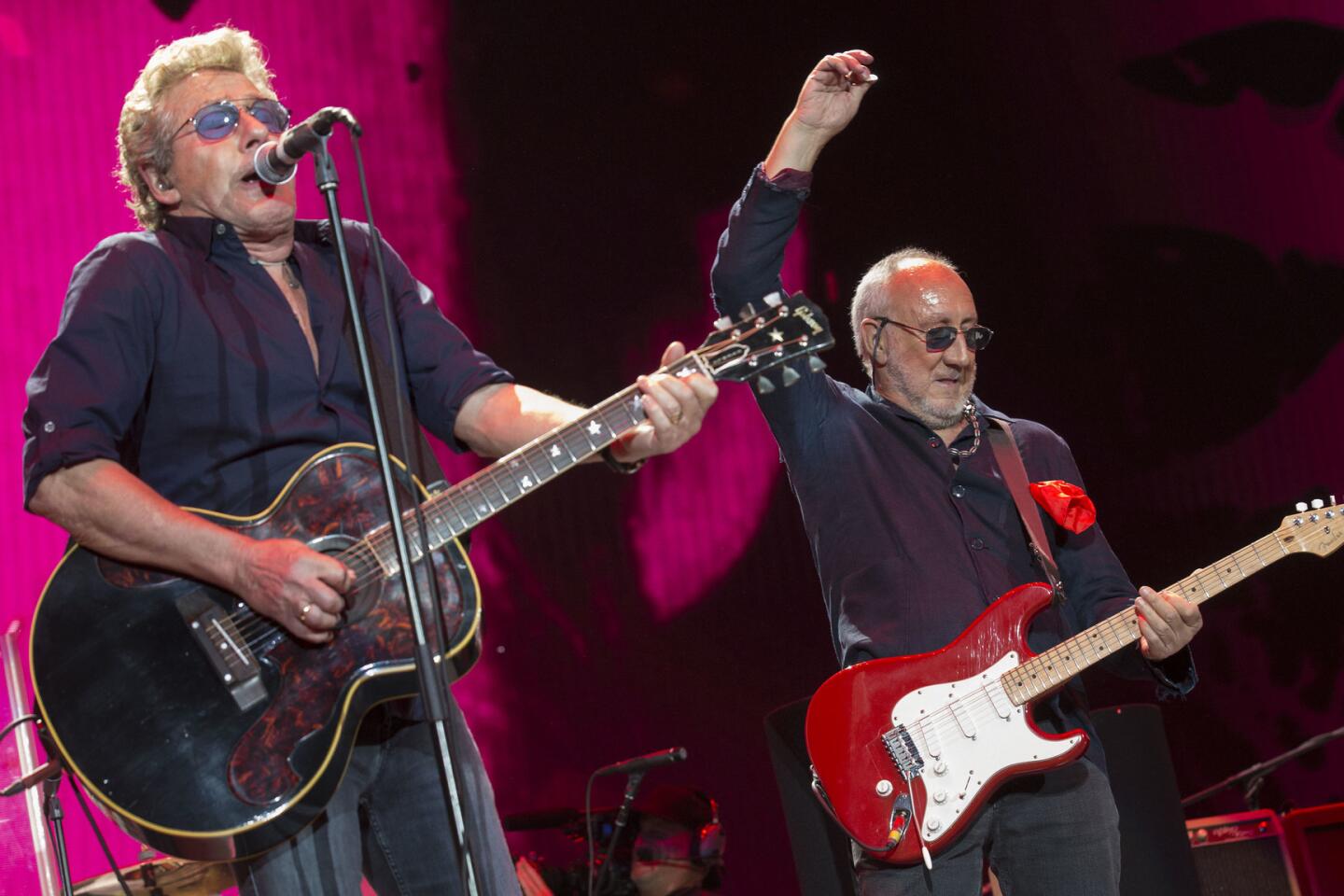

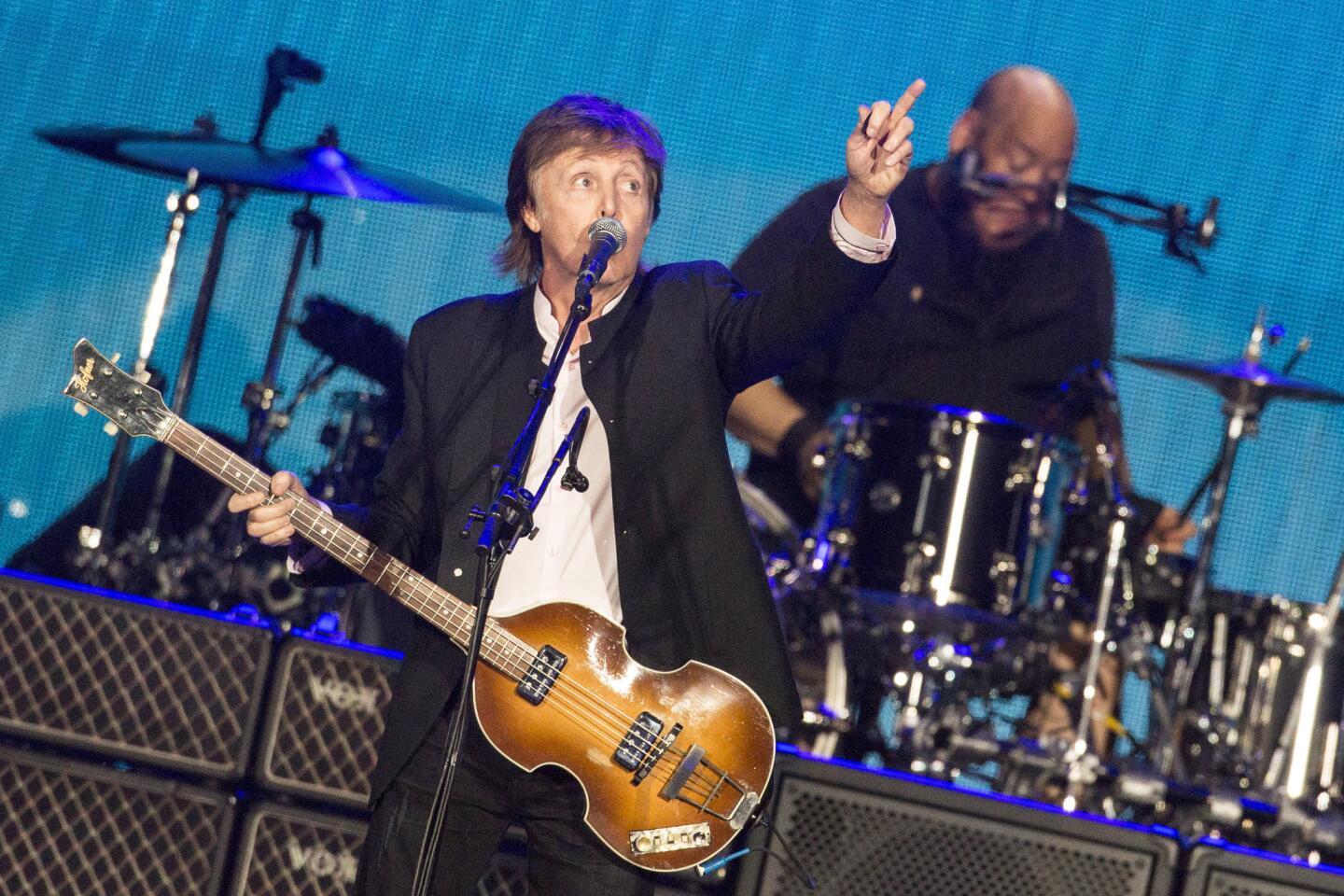

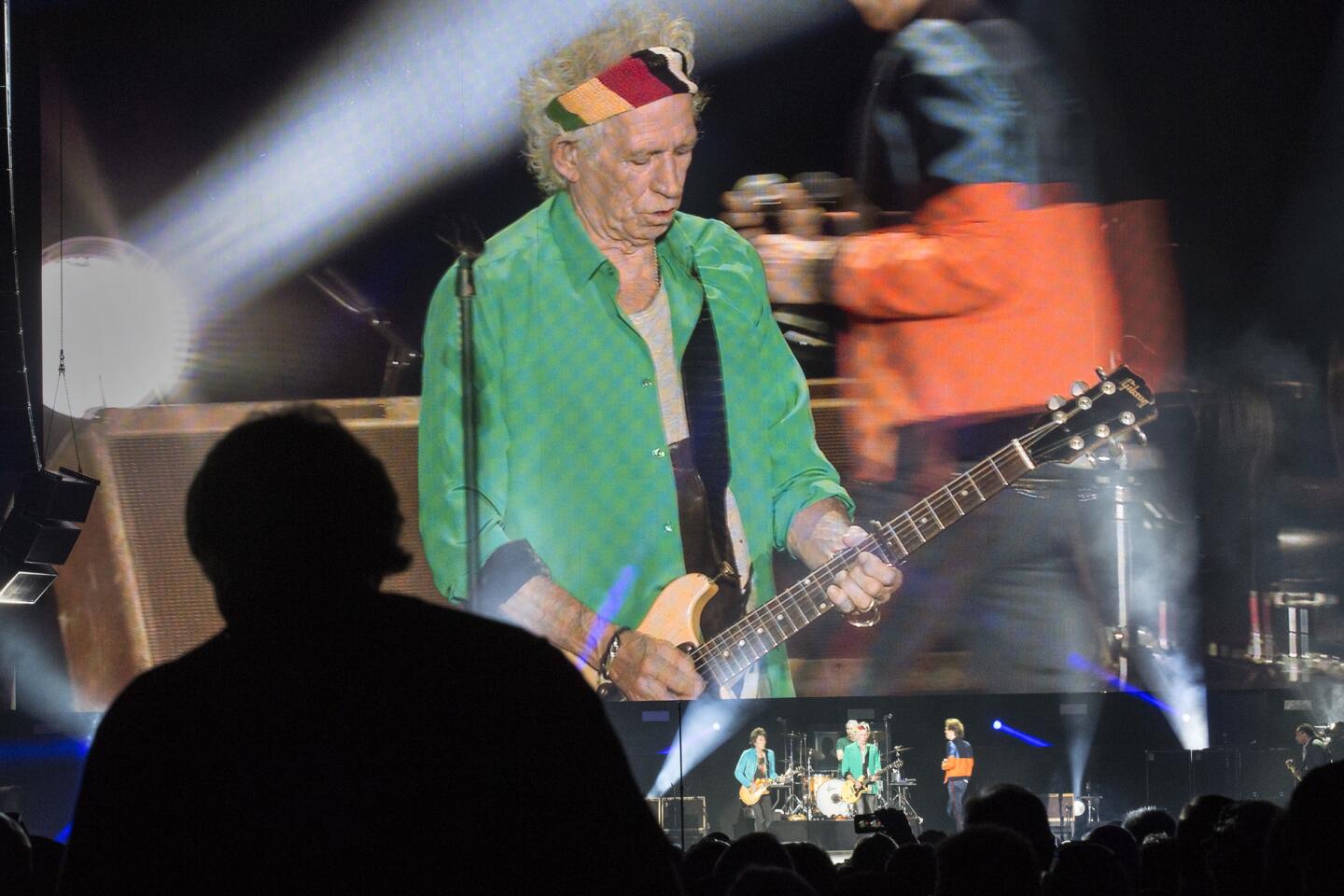

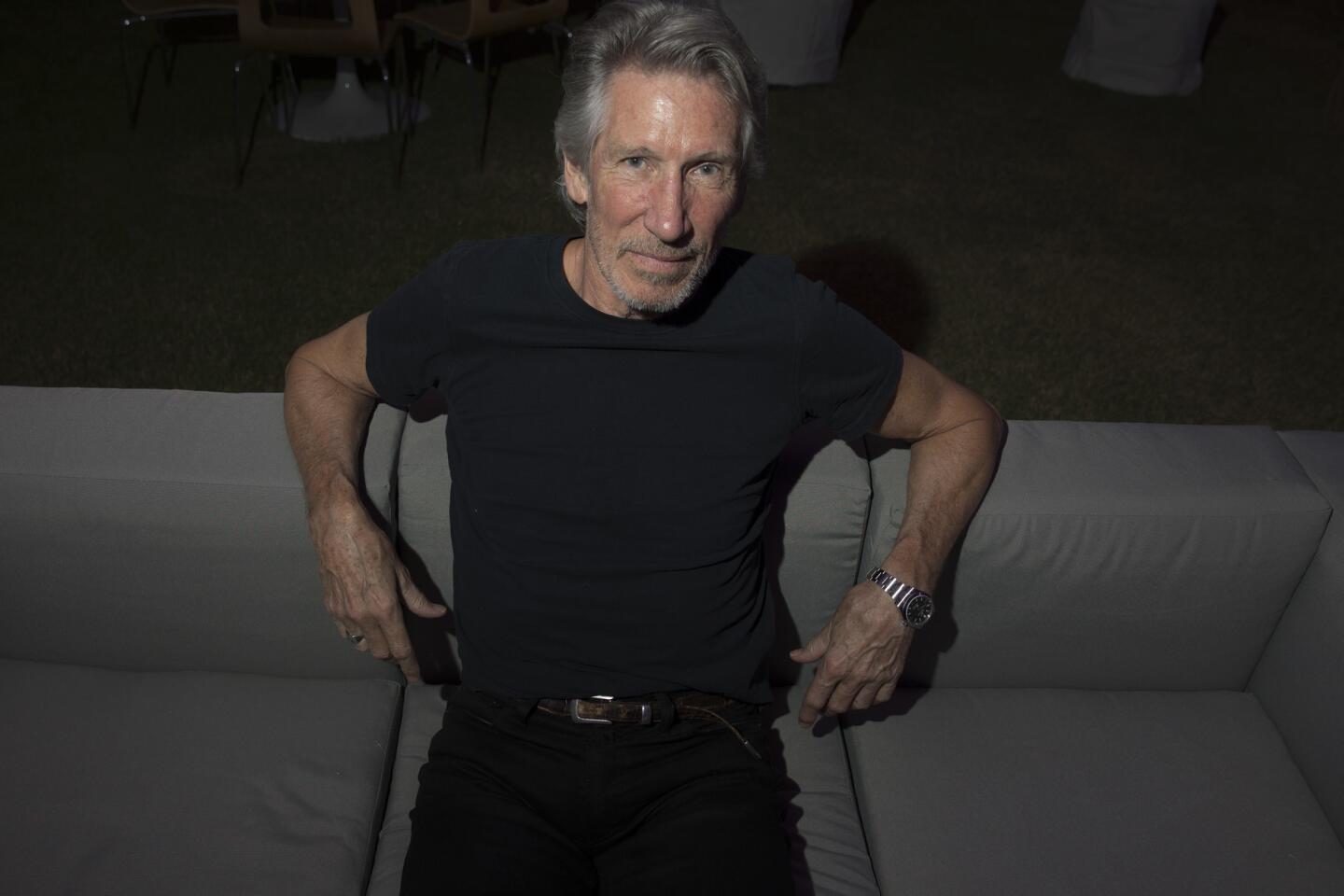

Starting Friday evening, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, Neil Young, Roger Waters and the Who will perform back-to-back sets over three nights at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, where the mega-concert’s promoter, Los Angeles-based Goldenvoice, also puts on the annual Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. Then the whole thing will repeat Oct. 14-16.

But let’s get real: Given how much money Desert Trip is expected to pull in — about $160 million, Goldenvoice’s Paul Tollett has said, nearly twice what Coachella made in 2015 — the show is virtually guaranteed to come back in some form next year.

And the year after that. And the year after that.

Which leads one to ponder what future installments of the festival might look like — and how much of Desert Trip’s allure is sustainable beyond its ultra-hyped debut.

There’s no doubt that this weekend’s gathering has a kind of now-or-never vibe. With an average age of 72, Desert Trip’s headliners simply aren’t likely to keep touring for long, a fact that feels especially salient in a year that’s seen the deaths of an inordinate number of veteran musicians, including David Bowie, Prince and Glenn Frey.

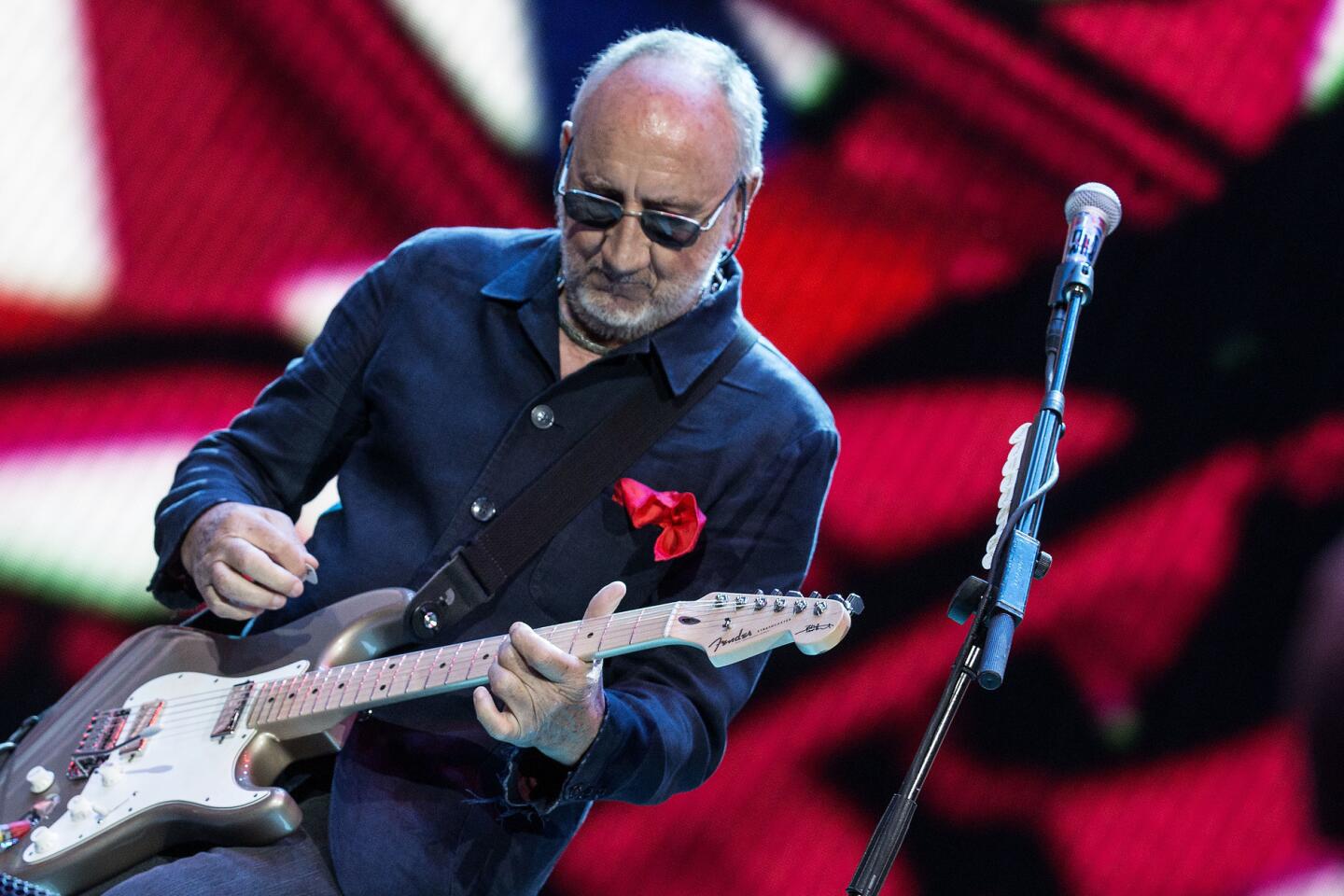

In other words, the Who’s Pete Townshend may have outlived his famous desire to die before he got old — but that just means he got old.

Upland resident Cindy Reul thought she would be permitted to bring a chair in the open-seating general-admission area, but was subsequently informed by email that, no, chairs and blankets wouldn’t be OK after all.

Implicit in the pitch for Desert Trip, though, is another, more problematic idea, and that’s the baby boomers’ widely held notion that rock music from the 1960s represents the last time pop mattered to a universal audience. In the decades since, the thinking goes, music has become too fragmented — or just too crummy — to embody the sort of monoculture that supposedly united the Woodstock generation.

In part this is nonsense: People didn’t stop listening because music got worse; they assumed music got worse because they’d stopped listening. Still, the withdrawal was real for many, which did indeed diminish that illusion of monoculture (to the great benefit of anyone who didn’t feel its embrace).

If that’s the view this festival puts forth, there are still some artists capable of upholding it next year or beyond: Eric Clapton, say, or Paul Simon, or the surviving members of Led Zeppelin, who according to show-business rumor turned down $14 million to play this weekend. (Perhaps $15 million is the magic number.)

It’s a fixed quantity, by definition, but the supply hasn’t quite been exhausted.

Yet considering these acts in isolation — and, boy, are there a lot of rich white men in this luxury cell — makes you question the persistence of their boundless appeal.

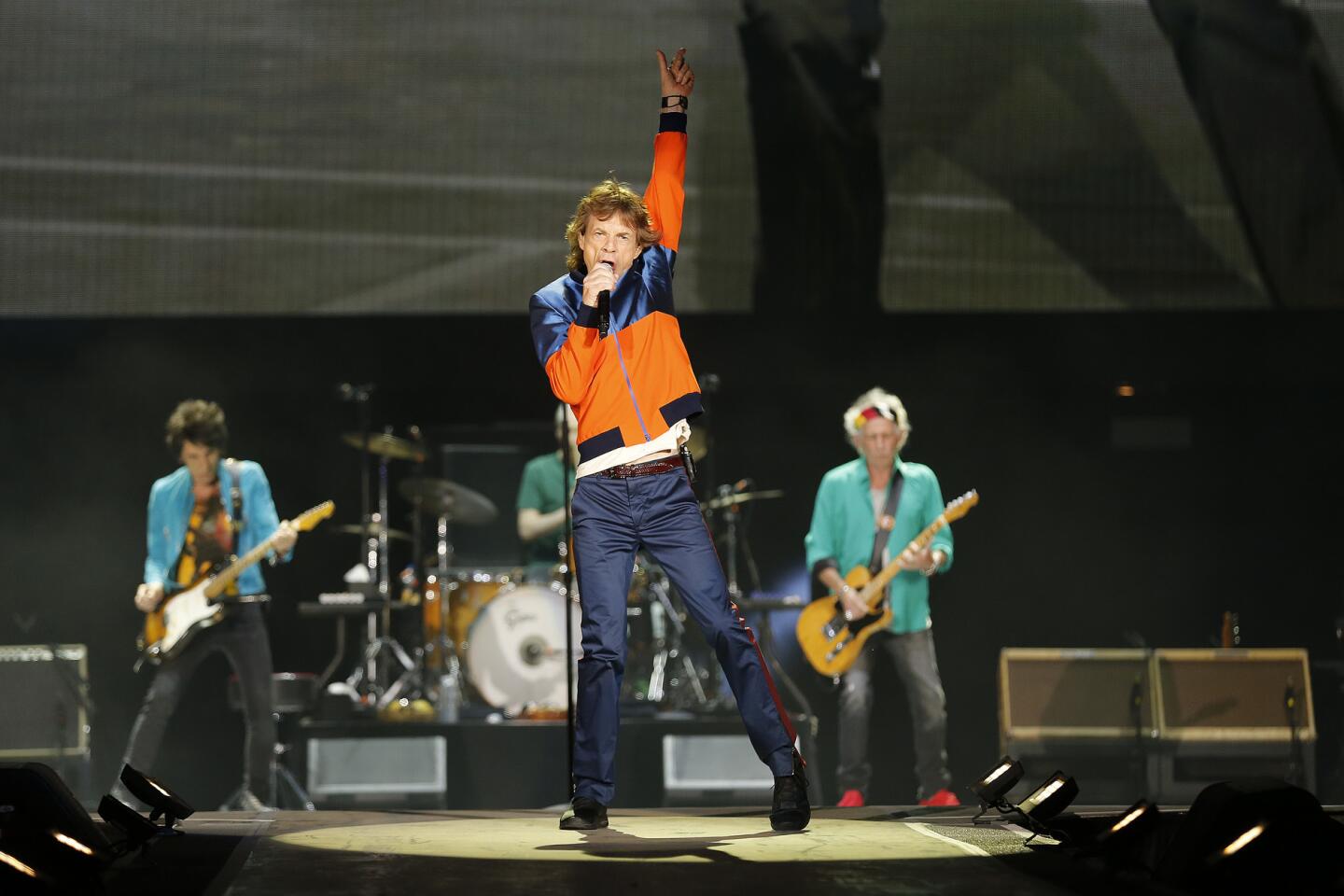

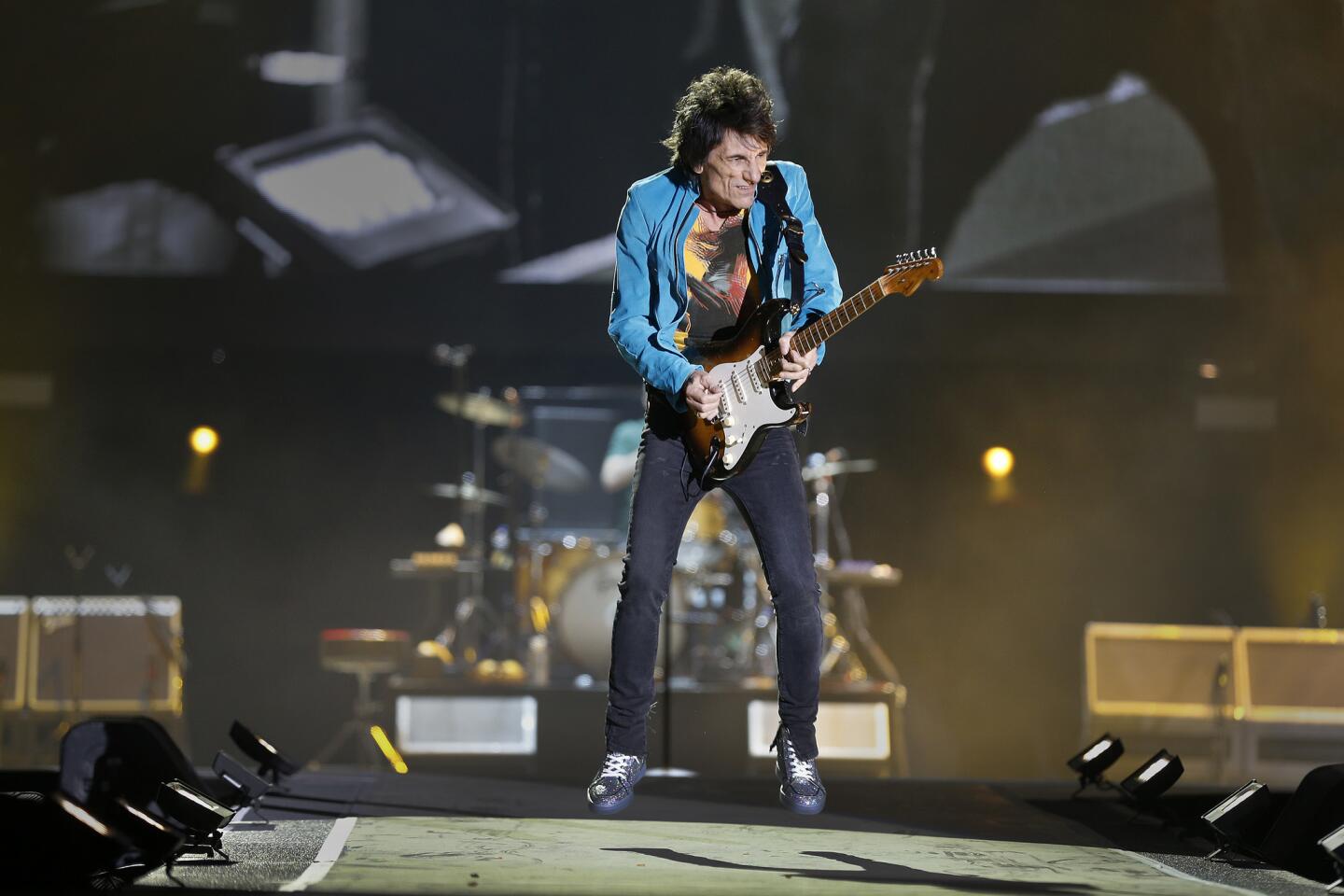

Sure, the Rolling Stones once spoke with as loud a megaphone as any artist has ever enjoyed; they achieved a type of omnipresence that’s nearly impossible to imagine now, at a moment when music fans can’t even agree on how or where to listen.

But this is the moment the Rolling Stones live in, no less than Garth Brooks or Gucci Mane. And today classic rock is just another niche on the satellite radio dial, with little advantage over any other except to those seeking reassurance of their long-held beliefs.

What will be fascinating to see at Desert Trip is how the headliners play against that reality (or don’t).

Certainly some of these guys are more eager than others to reach outside the box that a phrase like “classic rock” implies.

McCartney, for one, has worked on multiple occasions recently with Kanye West, including on an excellent 2015 single, “FourFiveSeconds,” whose hard-to-classify sound is precisely what we should demand from anyone purporting to speak for everyone.

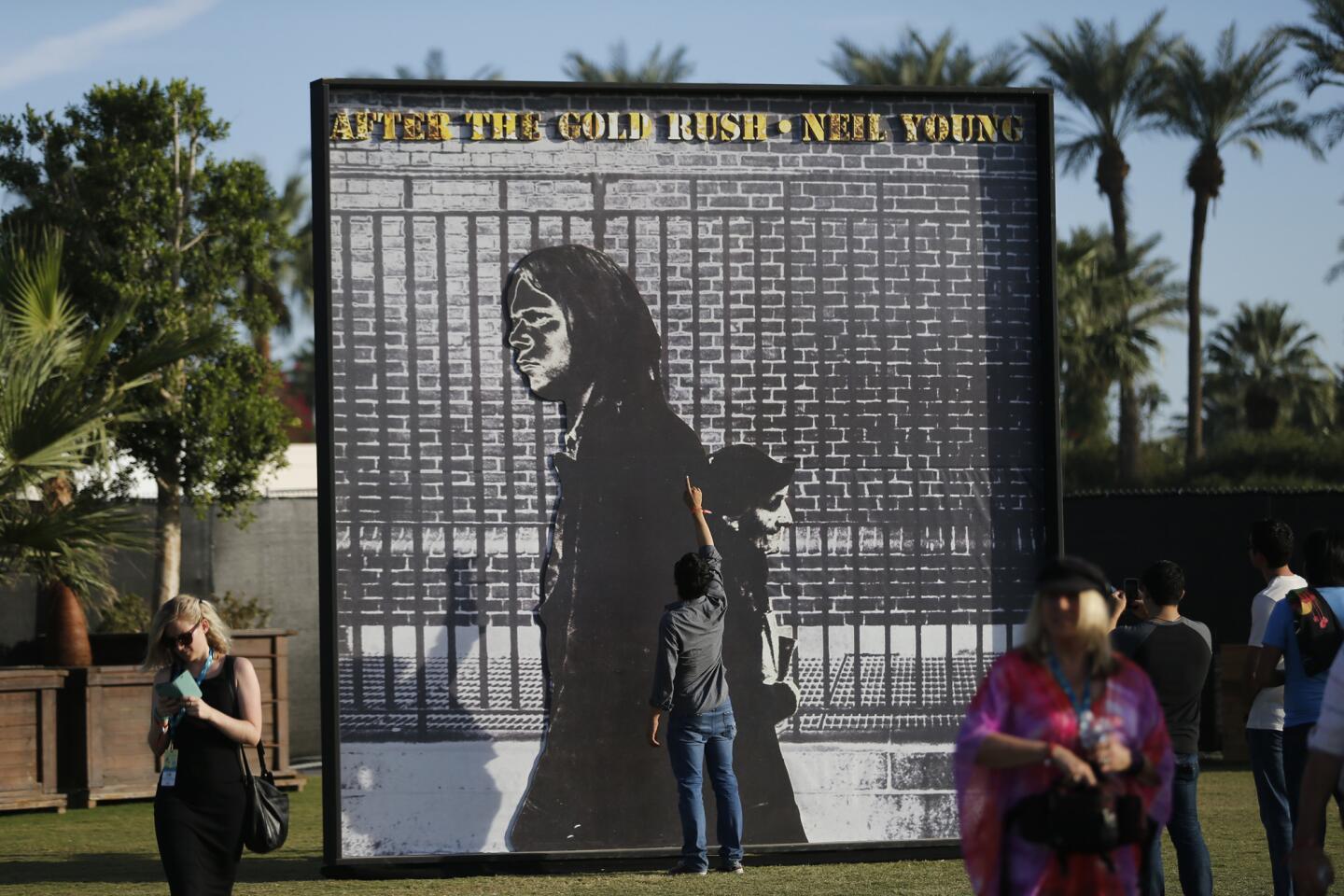

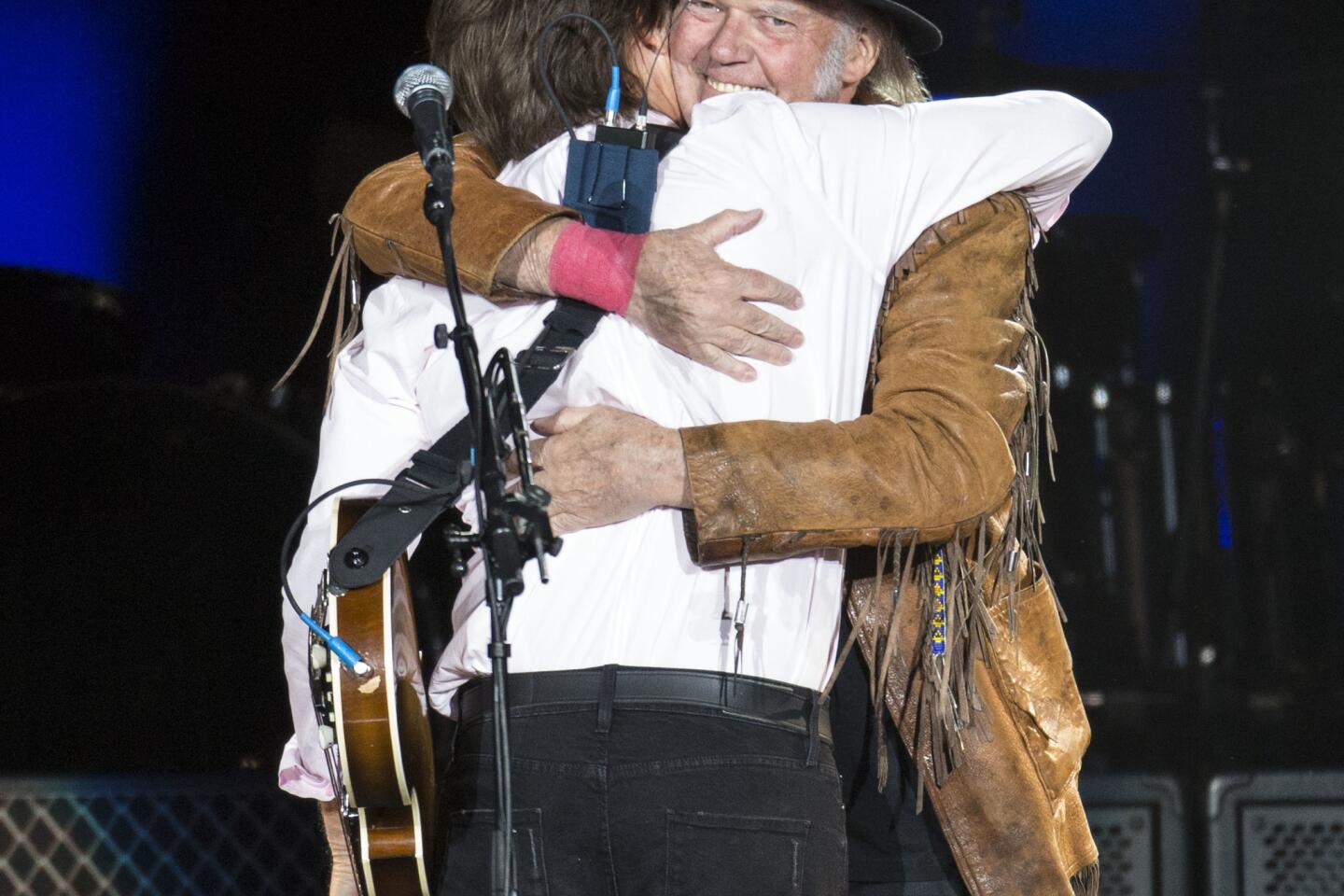

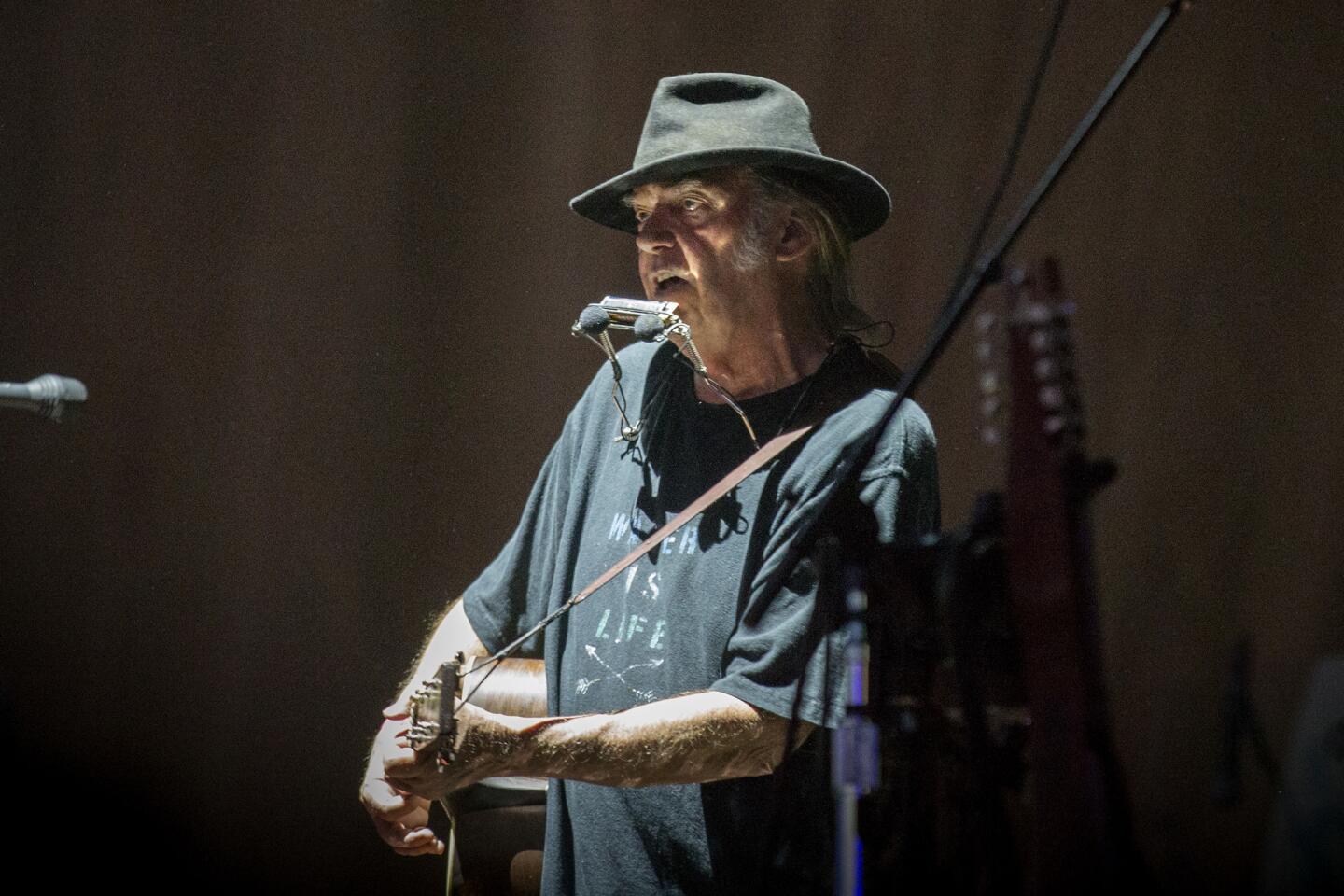

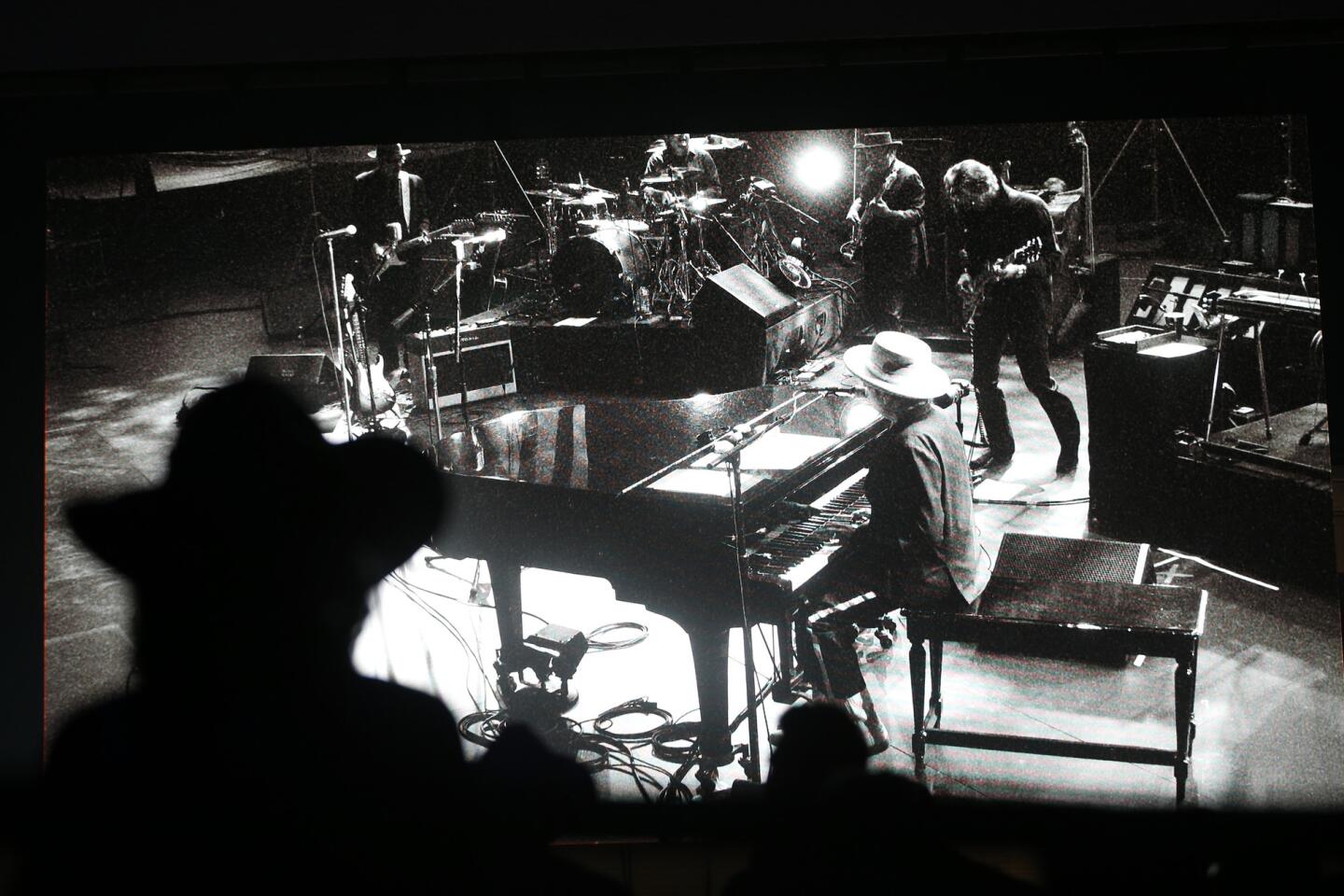

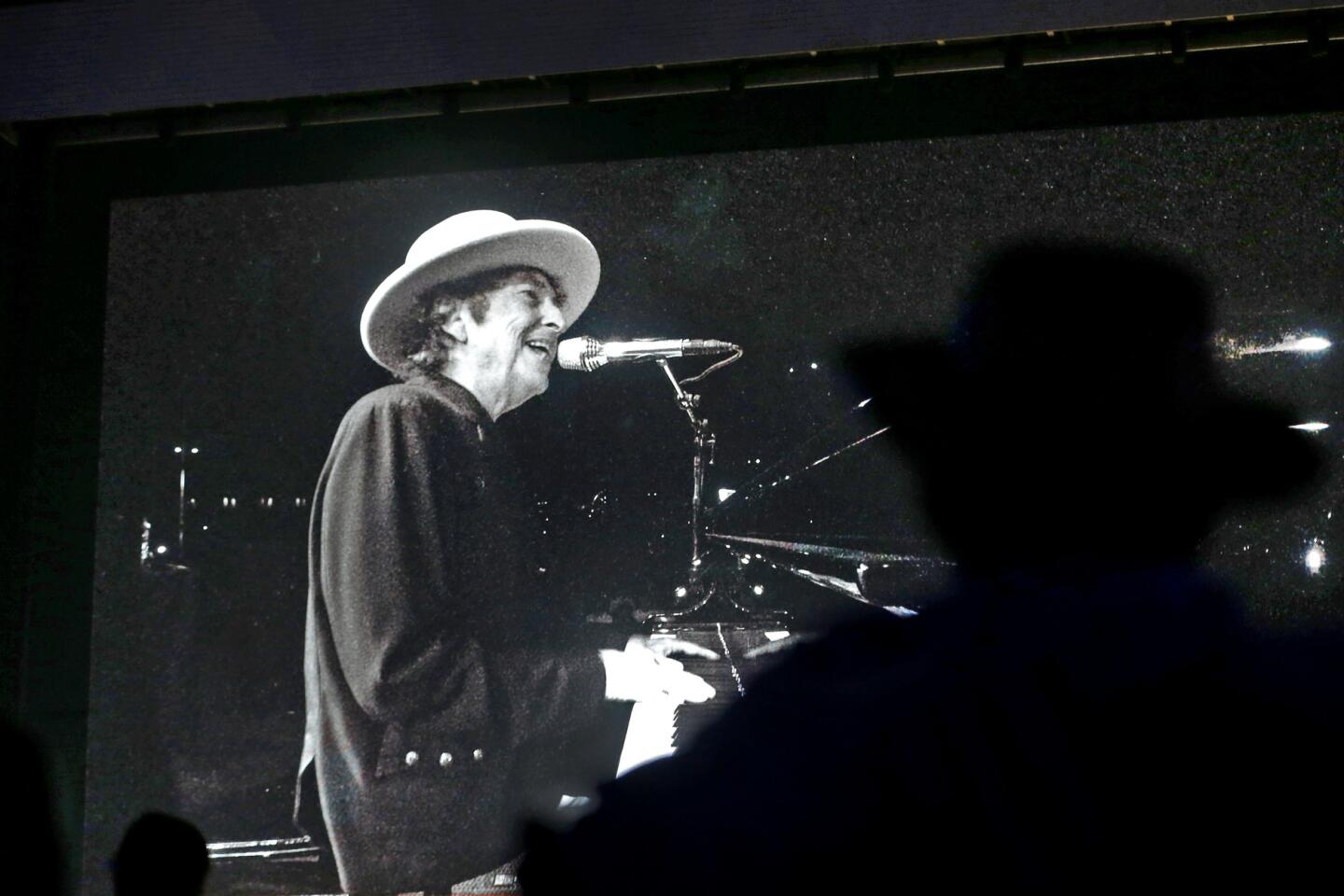

And Dylan, of course, seems morally opposed to rehashing his glory days — or even to fulfilling established ideas about himself and his music. Ditto Neil Young, who’s filled his catalog lately with a series of increasingly wacky projects such as a live record overdubbed with nature sounds. (On second thought, that might be Young in his purest form.)

The Stones, meanwhile, are said to be working on an old-fashioned blues record, which would suggest a retreat from pop’s front lines if the band’s recent 50 & Counting tour hadn’t featured forward-looking drop-ins from the likes of Lady Gaga and Mary J. Blige.

Should we expect that kind of stunt in Indio? There’s a festival crowd to consider, one sure to be full of folks who paid hundreds (or thousands) of dollars to be reminded of how much better it all used to be.

The first Desert Trip might end up taking people happily in that one direction. Or maybe it’ll lay the groundwork to go somewhere new.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

Rolling Stones announce first new studio album in over a decade, ‘Blue & Lonesome’

Going to Desert Trip? You get a Viewmaster

Steely Dan with strings at the Hollywood Bowl? ‘For some reason we decided we were gonna do this’

‘I overcooked it’: Randy Newman on stripping down his complicated music for his ‘Songbook’ series

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.