With ‘Spotlight,’ victims of child sex abuse by Catholic priests feel empowered

Phil Saviano says that when he first went public about the sexual abuse in the 1990s, he was dismissed as an eccentric.

- Share via

Frank and Virginia Zamora were among the last to file out of the movie theater. The couple had seen "Spotlight" before, but still it was a jolt. Especially watching one particular actor with green eyes. He looked a lot like their son, Dominic, who died last year following a battle with alcoholism, an addiction his parents believe began after he was molested at age 8 by a priest in the Los Angeles Archdiocese.

"One day, when he was about 12, he told us he didn't want to be an altar boy anymore," recalled Virginia. "He and his dad got into an argument. Frank said, 'It's an honor to be an altar boy.'"

"I was an altar boy," Frank interjected. "I always had respect for the priests. They were second to God."

"Spotlight," about the Boston Globe investigation that uncovered rampant child sex abuse within the Catholic Church, brings all these memories to the surface for the Zamoras. Which would seem to be a reason to stay away from the film and its Oscar campaign as it competes for six Academy Awards, including best picture.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Instead, the couple went out of their way to make the Culver City screening, which had all the trappings of an awards season gathering: a logo-patterned backdrop for photos, chicken skewers, a Q&A with movie talent.

But in place of academy voters swapping film recommendations in the lobby, there were survivors huddled close together, sharing emotional stories and trading phone numbers. This is why the Zamoras had come. They wanted to see "Spotlight" with others who had been affected by child sex abuse.

Because after their neighbors in La Mirada found out what happened to Dominic at St. Paul of the Cross, they were shunned.

"We lost friends. We lost relatives," Virginia said quietly. "He was a child! Wait until you've walked in our shoes all these years and have been there with the tears and the sadness. You know nothing."

Rachel McAdams said she was “proud to be part of a film that literally is giving voice to the voiceless -- that is speaking for a group of people who have been marginalized for decades.”

Rachel McAdams said she was "proud to be part of a film that literally is giving voice to the voiceless -- that is speaking for a group of people who have been marginalized for decades." (Kerry Hayes/Open Road Films )

Since "Spotlight's" November release, many abuse survivors and relatives have felt empowered to share their own harrowing stories — some for the first time. They've also been enlisted to join in the movie's awards season campaign by Open Road Films and Participant Media (the companies that produced and financed the picture), helping to underscore its societal influence.

Though the Globe journalists responsible for the Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage were a big part of the film's initial media push, in recent months the focus has shifted to the survivors. During a presentation at the Director's Guild of America awards in early February, Rachel McAdams, who plays reporter Sacha Pfeiffer, made sure to remind the crowd of the movie's gravitas, saying she was "proud to be part of a film that literally is giving voice to the voiceless — that is speaking for a group of people who have been marginalized for decades."

And at the Culver City event, director Tom McCarthy underscored the actress' point. He told the audience that attending the screening felt more meaningful than the majority of his other media obligations.

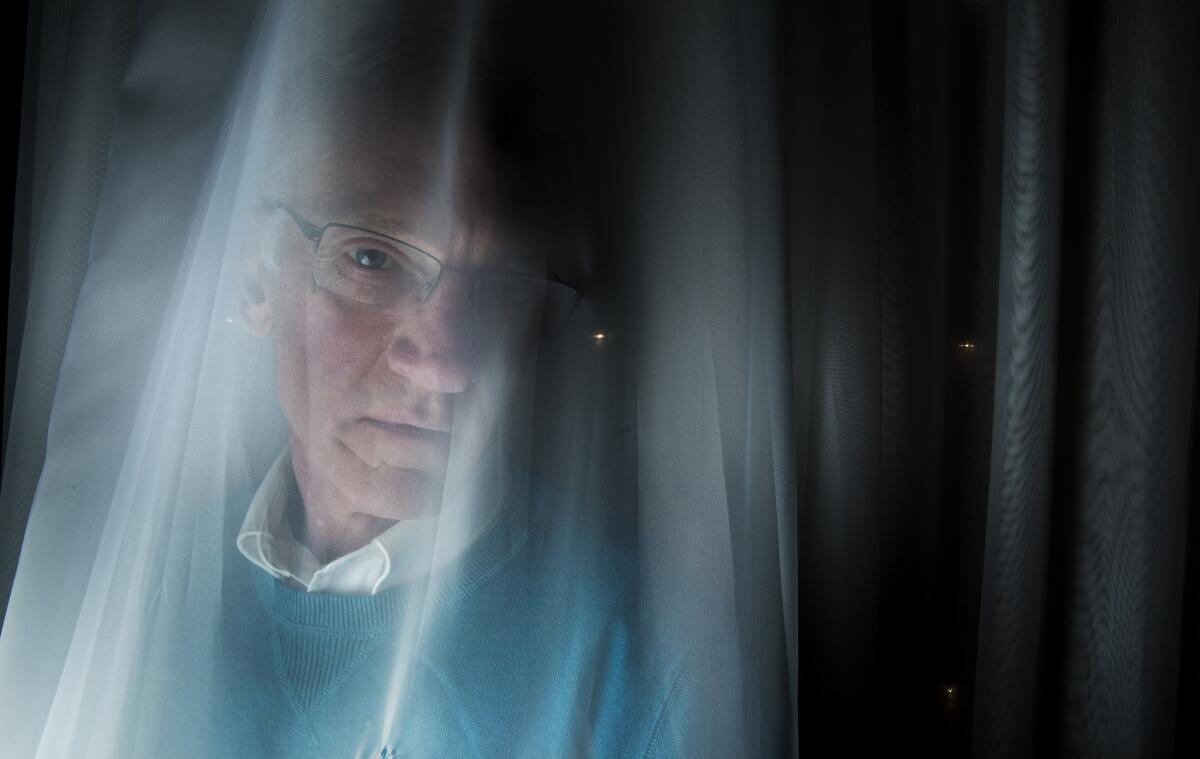

Phil Saviano, from left, a victim; Richard Sipe, who wrote several books on priests and sexual abuse; and Terry McKiernan, who runs a nonprofit group that tracks the scandal, attended the Culver City screening.

Phil Saviano, from left, a victim; Richard Sipe, who wrote several books on priests and sexual abuse; and Terry McKiernan, who runs a nonprofit group that tracks the scandal, attended the Culver City screening. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

"We've been running around like idiots, talking about ourselves and the film and pandering for any award anyone will give us," the filmmaker said with a smile. "But this does remind us, really, why we do the work, what got us involved and why we care so much."

Finding courage

More than two decades ago, when Phil Saviano first went public as a victim of clergy abuse, he was unable to imagine a day when strangers would openly relate to his story. As the head of the New England chapter of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, he visited the Boston Globe in the '90s to talk about the widespread abuse within the church. But as depicted in the film, he was initially written off as an eccentric, unreliable source.

"They saw me as one of those conspiracy theorists," said Saviano, who flew out from Boston for the survivors screening. "Honest to God — I always tried to present myself as being respectable. I always made sure I wore a jacket and tie because I figured if you're going to say bad things about a priest, you better look respectable."

Looking back, he says he had the courage to share his story only because he had AIDS and thought he would die soon. He couldn't keep a job. He was broke. He figured his reputation was shot, so it made little difference if he was further embarrassed. If he'd been married, or had kids, or worked for some important company, maybe he never would have opened his mouth, he said.

Many of the real-life figures whose stories are told in "Spotlight" believe the movie has done a lot to reduce that stigma. Mitchell Garabedian, a Boston lawyer who has brought successful cases against more than 150 alleged church perpetrators, said he's had an influx of sexual abuse victims contact him since the film's release.

Rachel McAdams, from left, as Sacha Pfeiffer, Mark Ruffalo as Michael Rezendes and Brian d’Arcy James as Matt Carroll in a scene from “Spotlight.”

Rachel McAdams, from left, as Sacha Pfeiffer, Mark Ruffalo as Michael Rezendes and Brian d’Arcy James as Matt Carroll in a scene from "Spotlight." (Kerry Hayes/Open Road Films )

"It's as though the movie is the beginning of the story for many victims," Garabedian, who is played by Stanley Tucci in "Spotlight," said by phone from his office. "I've always been extremely busy, but the film has caused a substantial spike in individuals contacting me from around the world — from Cambodia, Uruguay, Australia."

Jim Scanlan, who had used an alias for years when discussing his teenage abuse, decided to reveal his identity after watching "Spotlight." For decades, he didn't tell anyone that a priest at Boston College High School had abused him — not even his wife. And when the Globe uncovered what had happened to him, he agreed to be known in the paper only as "Kevin from Providence." (That's also what he's called in "Spotlight.")

"Everything has been a progression," said Scanlan, who is a financial planner. "Seeing the movie, I somehow understood much better that if I had been mugged in a park, I would not be afraid to tell anyone. And this should be no different. Seeing the movie really just flipped the switch for me that survivors are not the one who should have the shame."

Recently, Scanlan joined Saviano and fellow survivor Joe Crowley, whose story is also told in "Spotlight," for a meal with the filmmakers. They spent four hours together at a fancy restaurant laughing, recalled Crowley. No one drank alcohol.

"And I think that's why Jim came out publicly," said Crowley. "He saw the camaraderie and the relaxation we had about ourselves. I recently asked Sacha Pfeiffer if she thought I was a different Joe Crowley than the one she met in 2001. I feel like I'm so much more calm and relaxed — not nearly as angry or guilty or shamed. And part of that is talking — not keeping it bottled up."

All three men say they've received an outpouring of support since the film's release. Crowley will take calls from strangers referred to him by Pfeiffer. Saviano started a Facebook page, where he's noticed that more individuals in their 20s are coming forward than in the past.

"I'm not free of issues, but I'm in pretty good shape, and I like to hold myself out as an example of somebody who had some rotten experiences as a kid but got his head together and found ways to be productive," said Saviano. "My feeling is that this can't be the most important thing that ever happened in your life. You've got to find a life beyond this experience and find some joy."

ALSO:

Job 1 for Tom McCarthy in making 'Spotlight' was getting the actors and journalists on same page

Review: Radiant 'Spotlight' illuminates how the Boston Globe covered church sex scandal

'Revenant' vs. 'Spotlight' vs. 'Big Short': Best picture front-runners sharpen their Oscar pitches

Films once were an escape from work. Now, they celebrate it. What gives?

'Spotlight's' makers went for 'simple, unvarnished truth,' not sensationalism

What 'Spotlight' respects about the church-scandal-breaking journalists and the actors who play them

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.