Olivia de Havilland 101: Everything you need to know as the movie legend celebrates her 101st birthday

- Share via

In Hollywood, you’re never too old to sue.

At least not if you’re Olivia de Havilland, the much-beloved, two-time Oscar winner whose 1943 lawsuit against Warner Bros. resulted in the collapse of the binding long-term contract system and put the De Havilland Law on the books.

On Friday, on the eve of her 101st birthday, De Havilland announced that she was suing FX and Ryan Murphy Productions over what she alleges was the unauthorized use of her identity in the recent miniseries "Feud: Bette and Joan.”

Many women have fought for equal footing in Hollywood for years; De Havilland has now, officially, been at it in two centuries.

“Feud,” which chronicles the longtime rivalry between actresses Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, used De Havilland, played by Catherine Zeta-Jones, as a commentator about the women, their relationship and Hollywood throughout the eight-episode show.

De Havilland, who resides in France, filed the lawsuit in Los Angeles Superior Court, claiming that FX didn’t ask permission to use her name and identity and did not compensate her for the use.

According to a statement made by her attorneys, Suzelle M. Smith and Don Howarth, "the FX series puts words in the mouth of Miss de Havilland which are inaccurate and contrary to the reputation she has built over an 80-year professional life, specifically refusing to engage in gossip mongering about other actors in order to generate media attention for herself.”

The suit accuses FX and its partners of placing the actress in "a false light to sensationalize the series,” noting that all the other real-life players who are featured in the series are dead.

FX declined to comment on the lawsuit, and Murphy's team did not immediately respond to The Times' request for comment Friday. De Havilland’s team plans to file a motion seeking an expedited trial date because of De Havilland's age, although the action would indicate that De Havilland is not going gently anywhere any time soon.

No matter how the suit turns out, it is a remarkable moment even in a highly remarkable life.

Olivia 101: A primer of must-know facts

The winner of two Academy Awards, the living legend is best known for playing the demure Melanie Wilkes in the 1939 epic “Gone With the Wind,” as well as for her numerous on-screen pairings with dashing leading man Errol Flynn during Hollywood’s Golden Age. She’s also known for being half of one of Hollywood’s most-heated sibling rivalries.

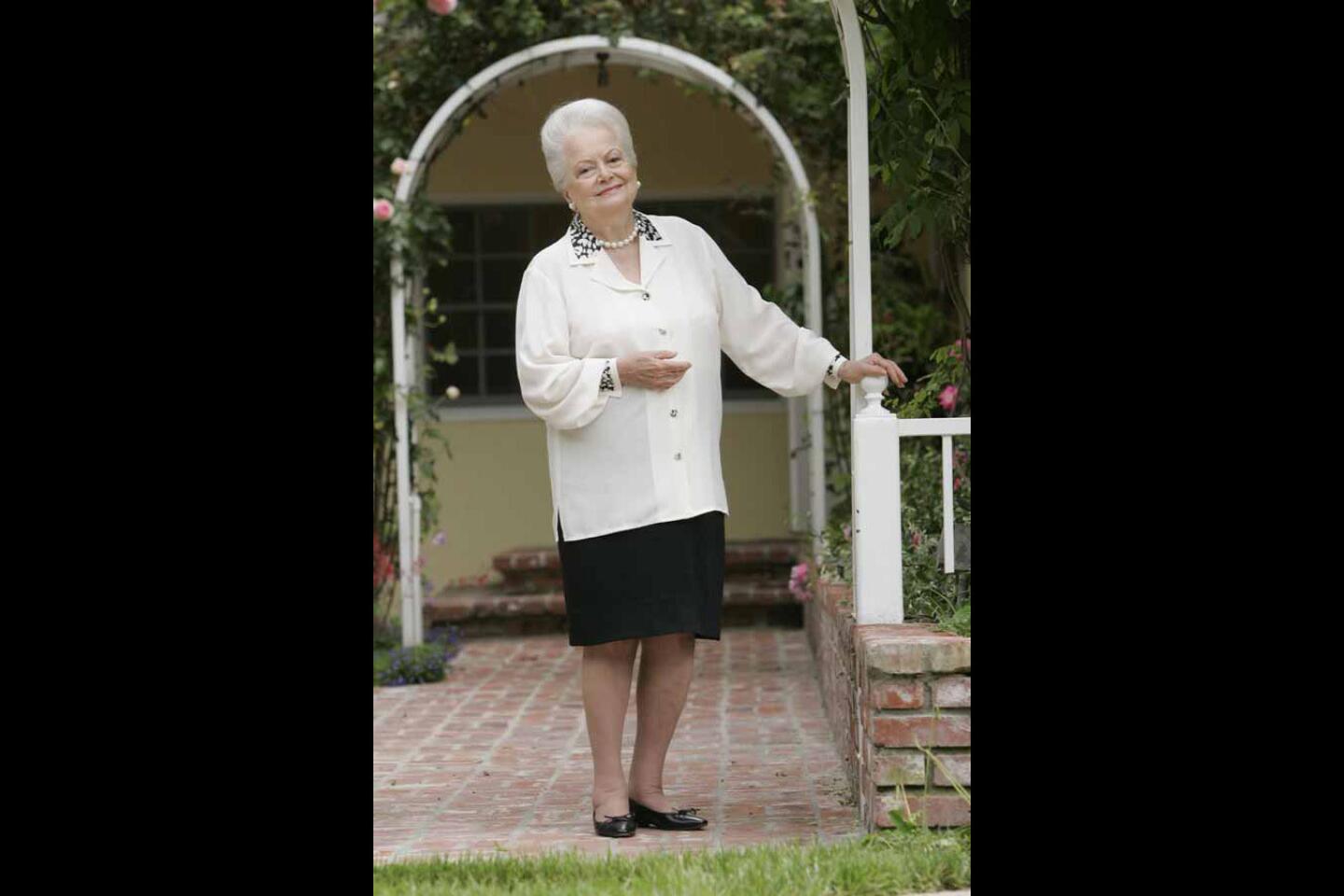

The newly minted English dame was dubbed by this newspaper as “the lady’s prototype of Lady, pretty-faced, gentle-faced and well-mannered.” The well-spoken pioneer’s chic coifs, expensive clothes and ever-present pearls are often noted.

De Havilland is also no stranger to legal proceedings. The acclaimed actress, who has worked in Hollywood since the 1930s, came up weathering Hollywood’s actor-studio contractual agreements long associated with early 20th century cinema — until she decided enough was enough.

Thanks in part to her 27-year-old self’s tenacity and leveling that landmark lawsuit against Warner Bros., the indentured servitude of the system began to collapse.

But first, a little background and a lot of Shakespeare.

De Havilland was born in Tokyo on July 1, 1916, to British parents. Her father, Walter de Havilland, headed a patent law firm in Japan, while her actress mother, Lillian Ruse, taught choral music.

She was named after the beautiful, sought-after lady of

De Havilland and her younger sister, fellow Oscar winner

Fresh out of high school and with a scholarship to Mills College, the 18-year-old actress deferred admission to appear in Max Reinhardt's staging of the Bard’s “A Midsummer Night's Dream” at UC Berkeley’s Greek Theatre. She would later become a second understudy in Reinhardt’s Hollywood Bowl production.

De Havilland referred to Reinhardt as “the greatest director in the world,” and, as luck would have it, she took the stage as Hermia when both her predecessors left the comedy before the premiere. Soon after that, Warner Bros. tapped Reinhardt to direct the studio’s flashy 1935 film adaptation with William Dieterle, leading De Havilland to a contract with the studio in 1934 and a starting salary of $200 a week.

As a contract player at Warner Bros., she made nearly two dozen films — eight of them with leading man Errol Flynn.

De Havilland’s “Shakespeare all the way” expectation of prestige roles at Warner Bros. was not to be so. The studio, known primarily for gangster melodramas led by male stars such as Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney, often typecast her as arm candy or in ingenue roles, often playing opposite fellow newcomer Flynn.

Together they became one of Hollywood’s most popular romantic duos, beginning with the swashbuckler "Captain Blood" (1935); their most enduring pairing is in “The Adventures of Robin Hood" (1938).

"I think of Errol all the time," De Havilland told The Times in 2006. "In different ways, almost every day…He really was a mixed-up man, but of course he was extraordinary-looking and had great charm." (The rakish matinee idol died of a heart attack in 1959 following years of philandering, heavy drinking and drug use.)

"But, oh, he did mean a great deal to me, but in that day a woman did not declare her feelings for a man,” she said. “When his autobiography came out, I couldn't resist checking the index and going to the page where he mentioned me. He said he thought he loved me. ‘Thought!’ That meant he didn’t! I didn’t read another word! Then several years ago when I was returning for the release of the DVD version of ‘Gone With the Wind,’ I was determined to read more. I began with his second sentence about me in which he said that he decided that he did love me. To think of all those years I didn't believe he did.”

De Havilland was also romantically linked to Howard Hughes, James Stewart, John Huston and several others. She married writer Marcus Aurelius Goodrich, author of the bestseller “Delilah,” in 1946, and they had a son named Benjamin before divorcing in 1952. A year later, De Havilland met Pierre Galante, a writer and executive of Paris Match magazine, and they wed in 1955, had a daughter, Giselle, and divorced in 1979.

She took on substantial roles while on loan to other studios, including MGM’s “Gone With the Wind.”

De Havilland took secret meetings to play “namby-pamby” Melanie in George Cukor’s sweeping drama “Gone With the Wind.” A top director at MGM, Cukor suggested “something entirely illegal” and asked De Havilland to surreptitiously journey to the Culver City-based studio and meet with producer David O. Selznick. The proposition easily could have incited legal action by Warner if the obstinate exec were to find out.

"[Cukor] said, 'Well, I'm going to suggest something to you which is entirely illegal. Would you come over to Selznick studios and read for the part?' He said tell no one, absolutely no one. I went to a secret entrance and they were waiting for me at the appointed time. They unlocked the door to the entrance and let me in to George's office,” she told The Times in 2004.

She read two scenes, committed them to memory and read them again for Selznick. He agreed to cast her in the epic if Warner would agree to loan her out. He didn’t agree.

“So I called up Mrs. Warner and asked her to have tea with me," De Havilland said. “She agreed and I told her how much the part meant to me. She had been an actress before she married Jack. She said, ‘I understand how you feel and I will try to help you.’ She was the one who persuaded Jack to let me go.”

The 1939 blockbuster earned 13 Academy Award nominations and won eight. De Havilland’s costar Vivien Leigh clinched the lead actress Oscar as Scarlett O’Hara, while De Havilland lost in the supporting category to costar Hattie McDaniel, whose role as Mammy made her the first African American entertainer to win an Oscar. But De Havilland’s nod further strengthened her resolve for more substantial roles in serious pictures.

De Havilland earned her second Oscar nomination for 1941’s “Hold Back the Dawn” at Paramount, playing an honest American schoolteacher in the romance.

She took on the studio system at age 27 — and won.

Though studio boss Warner jump-started her career, he would soon become De Havilland’s courtroom rival. When the studio lobbed roles she deemed unacceptable, De Havilland began taking unpaid suspensions as retribution. Following “Hold Back the Dawn,” she waited out her seven-year contract, which was set to expire in 1943, eager to take on meatier parts elsewhere.

However, California labor statutes favored employers at the time, and the “peonage” law, as she called it, meant the studio was entitled to six more months’ worth of work and could tack on her suspension penalties to the end of her contract. De Havilland took them to court, was backed by the Screen Actors Guild, and the battle went all the way up to the Supreme Court of California, which ultimately ruled in her favor by deciding that contracts had to be restricted to seven calendar years of service.

Decades later, De Havilland’s legal precedent helped musician and future Oscar winner

The nominations kept coming and so did the Oscars. And she had pal Bette Davis to thank.

In all, De Havilland was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning two.

OSCAR TALLY

- NOMINATED: supporting actress, “Gone With the Wind” (1939)

- NOMINATED: lead actress, “Hold Back the Dawn” (1941)

- WON: lead actress, “To Each His Own” (1946)

- NOMINATED: lead actress, “The Snake Pit” (1948)

- WON: lead actress, “The Heiress” (1949)

After her nods for “Gone With the Wind” and “Hold Back the Dawn,” De Havilland earned her first Oscar in 1947 playing an unwed teenage mother in 1946’s romantic drama “To Each His Own.” She received another nod for Anatole Litvak’s “The Snake Pit” portraying a young wife flung into a mental institution “at a time when there was still a medieval attitude toward mental illness,” she said.

“I believed in following Bette Davis’ example,” she told The Times in 1988. “She didn't care whether she looked good or bad. She just wanted to play complex, interesting, fascinating parts, a variety of human experience. I wanted Melanie to be just one of the images. Let's have a few others.”

While the "The Snake Pit” meant the most to her, it was her role as a spinster in William Wyler’s adaptation of cruelty-oozing "The Heiress" that garnered her second Academy Award.

De Havilland said that her first Oscar win had been marred by her sister, which leads us to…

Her infamous feud with her sister, Joan Fontaine, led to a notorious rebuff at the Academy Awards.

The press jumped on De Havilland and Fontaine’s sibling rivalry even before the 1941 Oscars race — they pulled each other’s hair and had savage wrestling matches as children, and went after the same parts and the same men as adults.

“You see, in our family, Olivia was always the breadwinner, and I the no-talent, no-future little sister not good for much more than paying her share of the rent," Fontaine explained to columnist Hedda Hopper in 1949.

The plot thickened when Fontaine delivered her Oscar-winning performance as the threatened wife in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Suspicion,” the same year for which De Havilland was nominated for “Hold Back the Dawn.”

Fontaine, who by her career’s end was nominated for four Oscars and won one, once compared herself to her sister this way in 1978: “I married first, won the Oscar before Olivia did, and if I die first, she’ll undoubtedly be livid because I beat her to it!”

When De Havilland won her first Oscar for “To Each His Own,” Fontaine allegedly reached out her hand to congratulate her, but De Havilland quickly turned away, her Oscar clutched to her breast — an infamous moment that De Havilland disputed.

Sister vs. Sister: What happened Oscar night

De Havilland

- “Look, these pictures [of us] cannot be taken unless Joan apologizes to me. I will turn away,” De Havilland told her press agent. “They didn’t believe me. They thought I would be just as phony as anyone. I came offstage. I trusted them. I had won the Oscar. This was the great moment of my life. It was totally ruined.”

“That year, backstage at the Oscars I wouldn’t speak to her,” De Havilland explained to The Times. “Let’s get it straight. My sister is very witty, and she made a remark about my first husband that came out in the Hollywood Reporter… I’m extremely loyal — savagely, not screamingly loyal — but savagely. My mother was Victorian and I was brought up on Victorian novels. If you were offended by a person, you never got angry. You just cut them dead. Read the novels. What’s required is an apology. Now, Joan knew that. She’d read the novels. A basket of flowers with just a name would have done it.”

I married first, won the Oscar before Olivia did, and if I die first, she’ll undoubtedly be livid because I beat her to it!

— Joan Fontaine in 1978 on her sibling rivalry with De Havilland

Their feud continued on and off for years until they were said to have had their final falling out in 1975 over their mother’s declining health. But De Havilland said they privately patched things up and expressed her sadness when Fontaine died at 96 in 2013.

After retreating to Paris, she was lured back to Tinseltown now and again.

The actress appeared on the screen intermittently until she retired in 1988. She famously replaced Joan Crawford in Robert Aldrich’s “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?” follow-up “Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte” in 1964, sharing the screen with her pal Davis, who famously feuded with Crawford (as seen in the 2017 miniseries “Feud: Bette and Joan.”)

She also starred in the thriller “Lady in a Cage.” She made her last feature appearance in 1979’s “The Fifth Musketeer,” though she did appear in several 1980s TV series, including “The Love Boat,” “North and South, Book II” and “Anastasia: The Mystery of Anna,” for which she was nominated for an Emmy Award. Her final picture was CBS’ 1988 movie “The Woman He Loved.”

But Tinseltown beckoned her for various anniversaries and celebrations of her films, particularly “Gone With the Wind” and retrospectives of her career. She memorably appeared at the 75th Academy Awards to showcase past winners gathered onstage.

She’s a dame, in the most respectful sense of the word.

Though a nun who taught her in Catholic school referred to her as a "brass monkey" because she would always get herself into trouble, De Havilland’s lady-like perfection earned her the title Dame Commander during

She was also appointed a chevalier of France’s Legion of Honour in 2010.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.