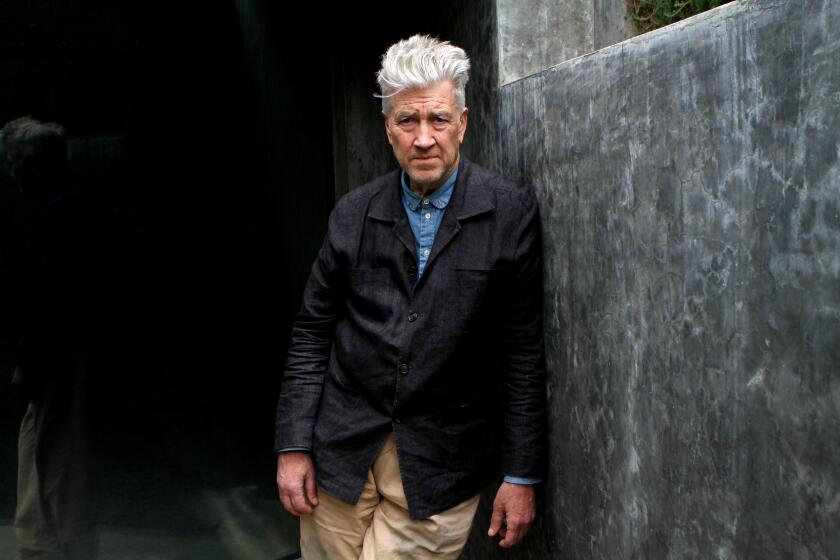

Mike White on the pathetic and the privilege in ‘Brad’s Status’

- Share via

Reporting from Toronto — While introducing the world premiere of the movie “Brad’s Status” at the recent Toronto International Film Festival, the festival’s creative director, Cameron Bailey, called the movie’s writer-director, Mike White, “one of the key voices in defining what comedy is in the 21st century.”

Though White might instinctively balk at such apparent hyperbole, it is not untrue. Born in Pasadena, White is particularly attuned to the stinging little aggressions of everyday life, the ways in which people inadvertently show their own anxieties and insecurities across issues of class, race, gender and privilege. With his eye for stinging satire and ear for the comedically uncomfortable, White might be thought of as the crown prince of cringe.

Yet he is no snob, his work crossing over between film and TV, the esoteric and the commercial for his entire career, from early work as a writer and producer on “Dawson’s Creek” and “Freaks and Geeks” to screenwriting on films such as “The Good Girl” and “School of Rock.” He wrote every episode of the two seasons of the HBO series “Enlightened” starring Laura Dern and directed numerous episodes as well. He even shared a writing credit on this summer’s “Emoji Movie.”

“Brad’s Status” is only the second feature film White has directed, after 2007’s “Year of the Dog.” In the new movie, Ben Stiller plays Brad Sloan, who runs a small nonprofit consulting firm in Sacramento and quietly enjoys a secure upper-middle-class life. He has seen friends from college go on to greater things — White makes a brief appearance as a successful Hollywood film director — and is overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy and jealousy. When he takes his high school-age son on an East Coast college tour, things unexpectedly come to a head after Brad discovers his son has a pretty good chance of getting into Harvard.

Earlier this year, “Beatriz at Dinner,” written by White and directed by longtime collaborator Miguel Arteta, became a low-key hit, bringing in more than $7 million at the box office. There was something especially topical in its tale of a spiritual healer, played by Salma Hayek, who crosses paths with a rapacious real estate developer who also enjoys big game hunting, played by John Lithgow.

After a strong limited release opening following the Toronto premiere, “Brad’s Status” expanded to theaters nationwide over the weekend. White spoke with The Times just a few days after the Toronto unveiling.

If you know my work, I’m the least likely to write the straight-white-man whiny comedy, somebody with west-of-the-405 issues.

You’ve said that after “Year of the Dog,” “Enlightened” and “Beatriz at Dinner,” all of which had female protagonists, that you purposefully wanted to do something focused on a male character and male psychology. What were you specifically hoping to explore?

I do think it’s a little bit of a companion piece to “Beatriz at Dinner.” While they’re completely different, in a way, it’s speaking to and trying to get inside the mind of a guy who feels like he needs more and wants more. And wanting to speak to that in myself and others. I’ve written characters that sometimes test your compassion, your desire to want to identify, and I think in a way Ben’s character in this is ... one of the more difficult protagonists to have sympathy for. His life is good and he’s complaining about stuff.

I’ve had conversations with people where they see themselves in Brad, but it’s a side of themselves they really hate, that’s not cool and they don’t want to acknowledge. I felt like that would be an interesting thing to approach, as a dramatist, to try to unpack those feelings and then also have a little compassion for him even though he’s obviously flawed and isn’t enlightened in certain ways.

To speak to your question about the male part of it, I think that sometimes, my experience is that men — I mean women are careerist too — but I do think that men, so much of their sense of self, often all of their eggs are in this one basket. And I think that even when they have families they love, their whole sense of self and what they bring to the table has to do with their status in the world or how much of a success they’ve been. And there’s just something pathetic about it.

The movie turns toward the relationship between Brad and his son as the story goes on, and it’s as if Brad never really considered his son before they took this trip together.

I’m not a father, but I am a son. So I do relate to Brad and I see some of my dad in Brad. My dad had recently retired and spent most of the latter half of his life in nonprofits, as an activist, so he retired with not as much money as a lot of his peers. And I think there was a moment — he doesn’t live in that headspace as much as Brad, he’s actually a really wise person — but I do think there are certain milestones where you have to look back, it makes you question when you don’t have certain things that the society at large values, that say, “This is what a successful life is.” You end up taking stock or doubting your choices, wish that you had more to leave to your children or more for a cushy retirement or more security.

And I felt that I obviously see my dad as a real success, both professionally and as a person, and there’s a part of me that wanted to tell a story about a midlife crisis that becomes stealthily a father-son story and is leading to this moment near the end that is an affirmation from his son. There was a part of me that was like, “It would be nice to in some way say that to my dad.”

Tell me about the bar scene, where an Indian American female college student criticizes Brad for being self-absorbed, for his “white privilege, male privilege, first-class problems.” Was that a way of heading off people who might say all that about the movie itself?

Here’s the thing. If you know my work, I’m the least likely to write the straight-white-man whiny comedy, somebody with west-of-the-405 issues. What I find annoying about Hollywood movies where they live in great houses but you’re supposed to take their problems to heart, I feel like what’s being proffered there is that they’re an everyman. But it’s not really everybody’s story. And that’s where the satire of it comes in.

It’s interesting now. There are certain circles where a story about a guy like this isn’t even worth telling anymore. The time of this kind of movie is over, and you can’t tell this kind of story. Like this is contemptible that he has all this and has all this privilege. And I was trying to get to some of that, but, of course, you need the scene where someone sees you and hears you and is like, “Dude, you have enough. You are doing just fine.” But I agreed with him too, like, “I may be a cliché, but this is my life.” But I also agree with her, in that “Just don’t ask me to feel sorry for you.”

I do think that pain is universal and disappointment is universal. People can have a lot and still suffer. And that doesn’t mean that’s a more important thing to think about than someone who can’t put food on their table, but when I think about the things that actually make this world a darker place, it’s the people who have a lot and who feel the need to have more and then become the guy in “Beatriz at Dinner.” In a way, speaking to some of that in ourselves, as people who have privilege and have a lot, there is something still to be said about that issue. It’s still, I think, worthy of considering.

Follow on Twitter: @IndieFocus

Also

Ben Stiller draws from his experiences as both a father and a son in two new character-driven films

Q&A: Deniz Gamze Erguven explores the tremors of the L.A. riots with ‘Kings,’ starring Halle Berry

Brie Larson finds strength in lightness and whimsy with ‘Unicorn Store’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.