From the Archives: George Romero: Movies ‘are not perceived as an art form by the industry’

- Share via

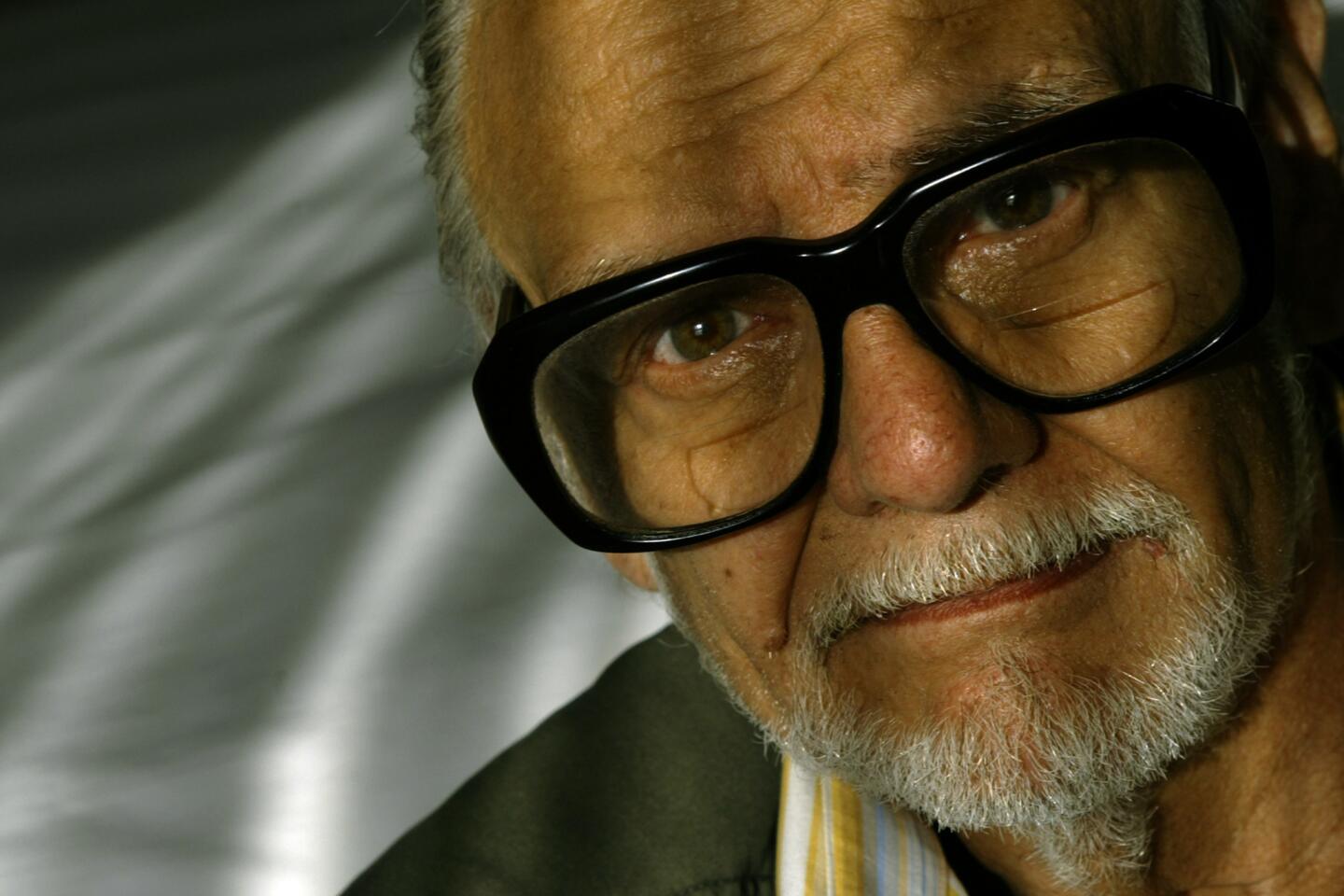

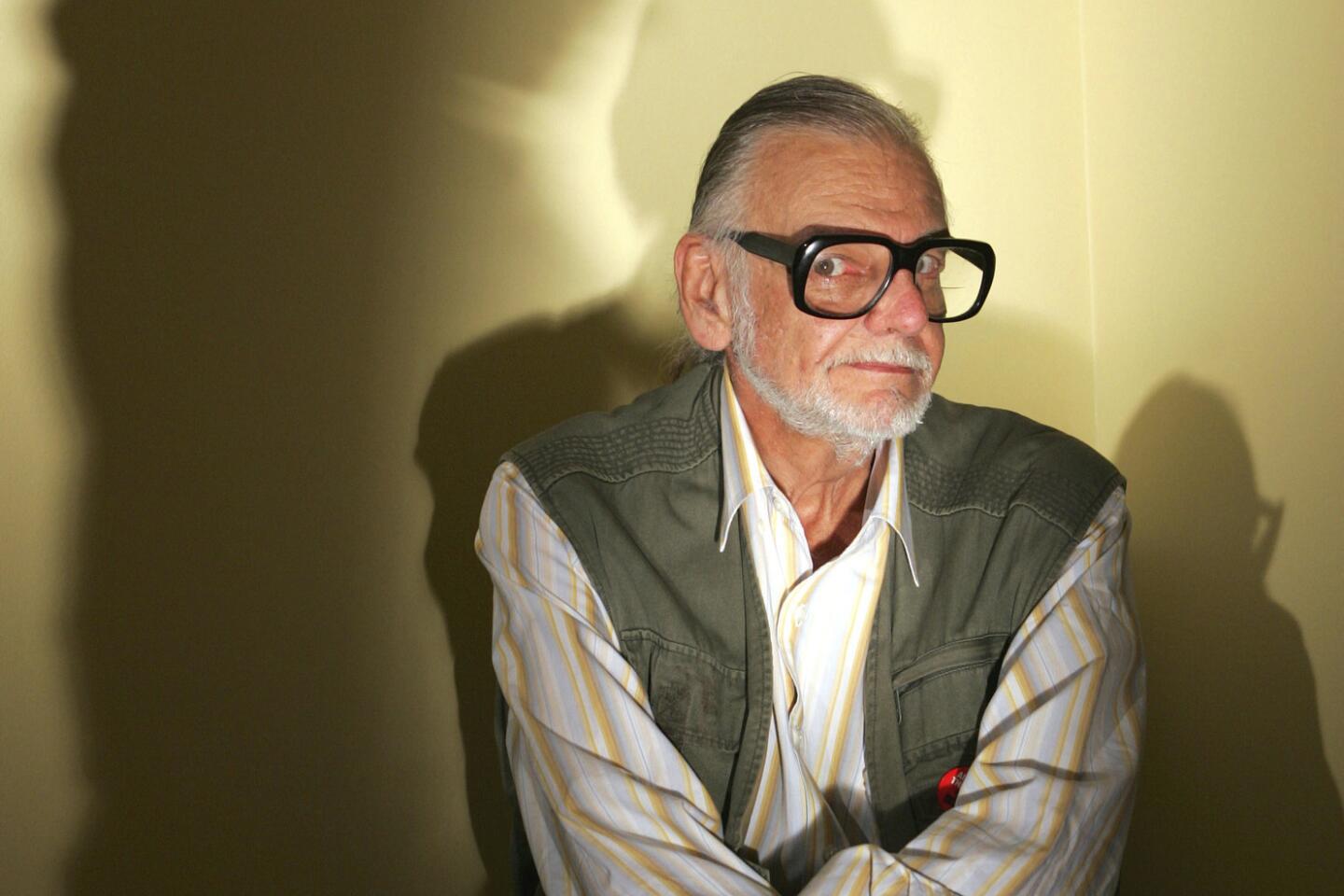

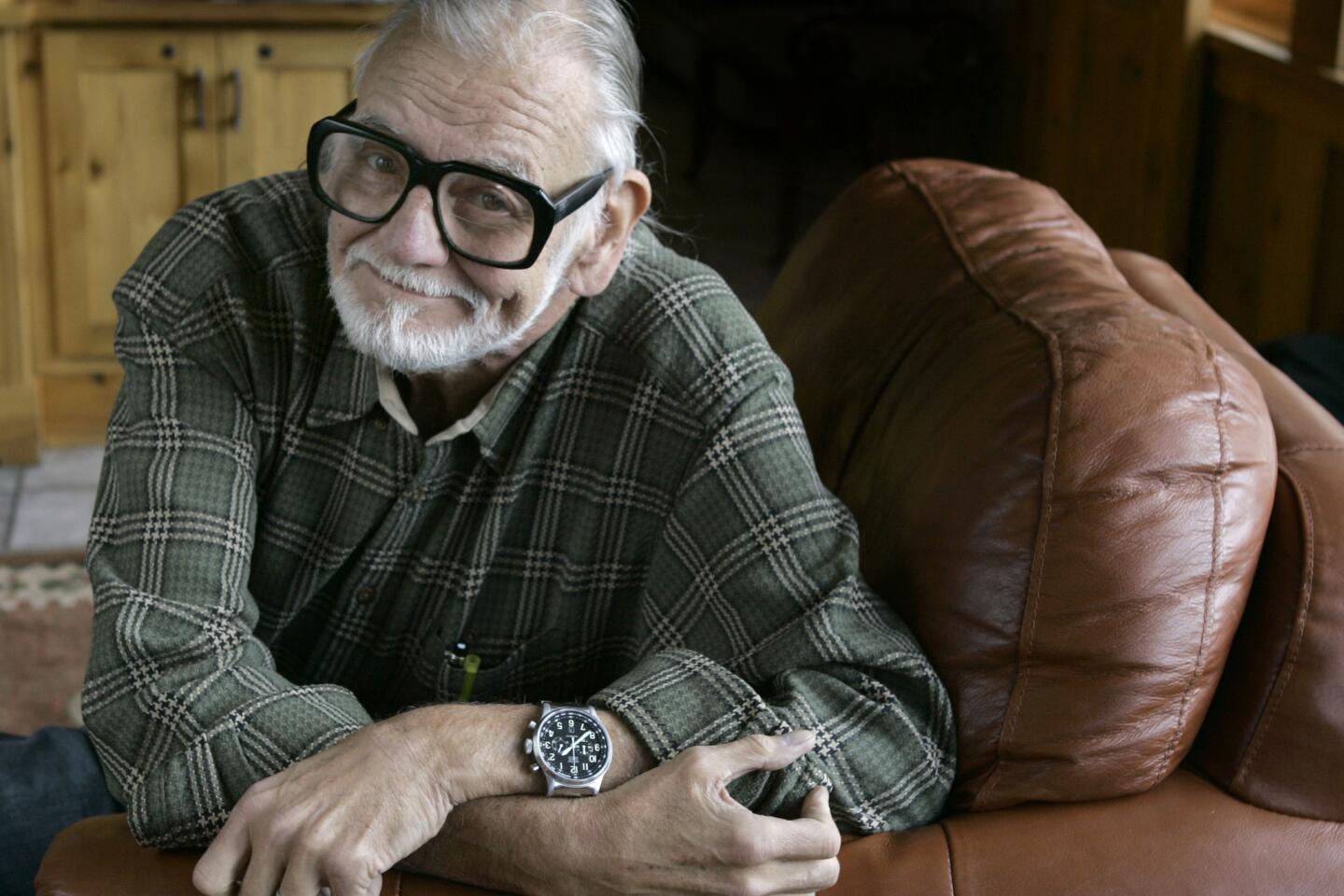

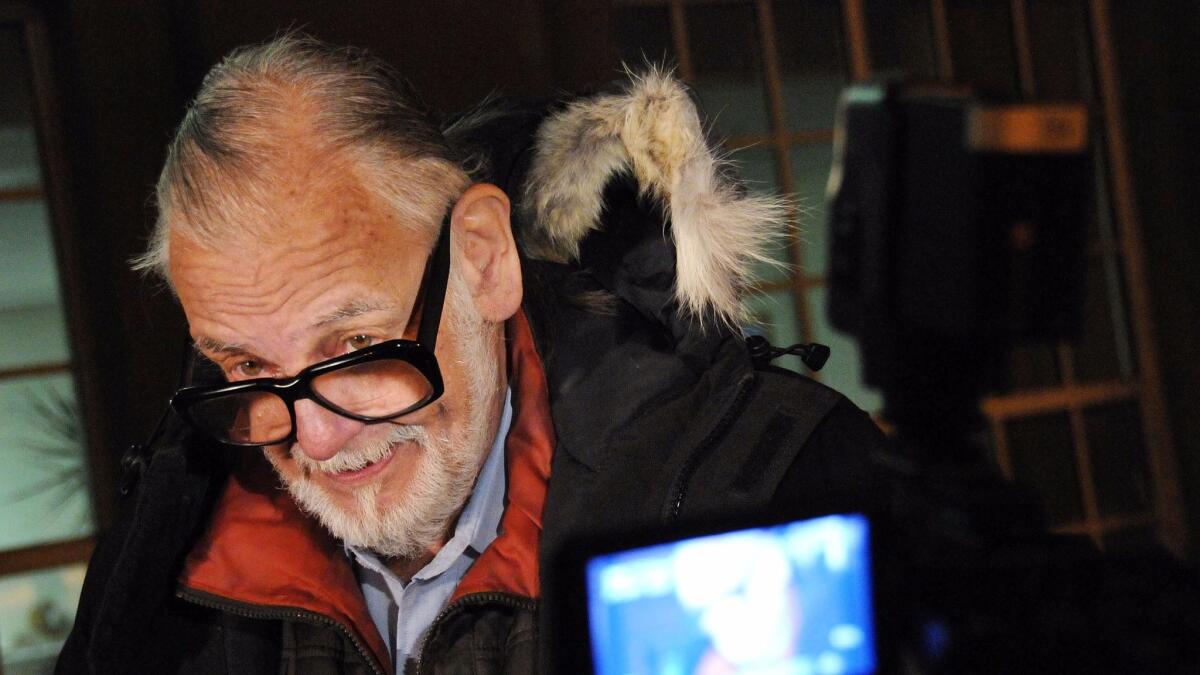

Filmmaker George A. Romero died on July 16, 2017, at 77. By columnist Patrick Goldstein, this article ran in The Times on July 31, 1988, with the headline “George Romero: Cinema With a Touch of Evil.”

Rush hour on Hollywood Boulevard.

Street toughs in black leather jackets compared new tattoos. A homeless man dozed in a doorway. A short-order cook stepped outside for a cigarette. Nearby, a teen-ager--perhaps an aspiring starlet--eyed publicity stills outside an aging movie palace.

“I know they’re trying to clean up Hollywood Boulevard,” said a big, bearded bear of a man who was eyeing the odd, colorful crowd. “But you’ll always be able to get a tattoo here. It’ll just cost more.”

Leave it to George Romero to celebrate tattoos. For the past 20 years, Romero has been making witty, grotesque horror films that get the kind of outraged reviews you’d expect from a hungover sailor after a night at a dockside tattoo parlor.

Daily Variety dubbed “Night of the Living Dead” a film of “unrelieved sadism . . . which casts serious aspersions on the integrity of its makers.” And the trade paper still doesn’t like Romero much--its reviewer panned his new film “Monkey Shines: An Experiment in Fear,” claiming “Darwin was wrong . . . after all, you don’t see monkeys making films like this one.”)

No matter. Made in 1968 for “70,000 cash,” “Night of the Living Dead” has become a pivotal signpost in the history of horror cinema. Since then, Romero has completed nine more films, proudly noting that “four have made money--and two have made lots of money.”

The 48-year-old director’s latest film, an unsettling exercise in psycho-terror, cost nearly $7 million. And Romero, a longtime Pittsburgh homeboy, says — perhaps with a tinge of false modesty — that any good reviews are gravy. He’d be happy to simply turn a profit.

“That’s how you’re ultimately measured in this town,” he said, ordering a beer at an old Hollywood eatery just off the boulevard. “Movies are a commodity. They’re not perceived as an art form by the industry.

“And that’s why I like the genre I work in. Because when I’m making horror films, I can slip those little messages in without anyone really noticing until they’re safely out of the theater!”

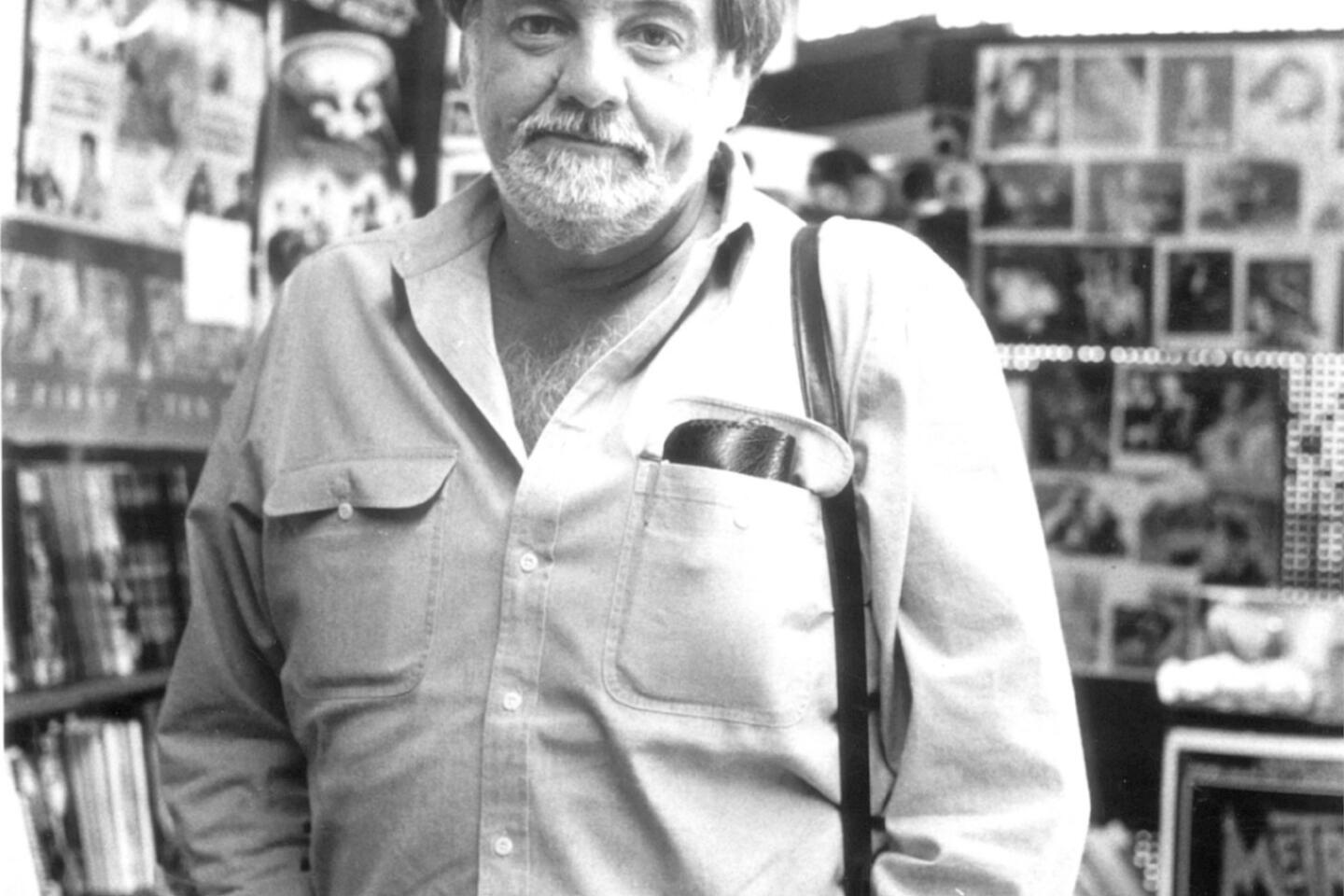

A gregarious man with an inquisitive air and an infectious belly laugh, Romero takes his notoriety in stride. Ducking into the Hollywood Book and Poster Shop, the director happily autographed a batch of “Monkey” posters, posed for a photo and greeted a longtime admirer, producer David Friedman, the self-acclaimed “Man Who Put the X Into Sex.”

Never a man to take himself seriously, Romero has often downplayed his films’ satiric fury. When asked about “Day of the Dead,” a gory chiller where zombies dressed as nurses and Hare Krishnas invade a Muzak-drenched suburban shopping mall, Romero dismissed the film’s gags as “like a wink or a handshake with the audience.”

When I’m making horror films, I can slip those little messages in without anyone really noticing until they’re safely out of the theater!

— George A. Romero

“Monkey Shines” digs deeper. It revolves around Allan Mann, a bright young law student and track star whose spinal cord is shattered during a jogging accident. Paralyzed from the neck down, Mann is given a monkey who’s been trained to serve the needs of quadriplegics.

But this is no ordinary monkey. A survivor of experimental-drug experiments conducted by Mann’s closest friend, the monkey is smarter--and deadlier. And as Mann, embittered by his sudden paralysis, slowly becomes consumed with the rage inside him, the monkey begins to inflame--and act out--his master’s most venomous thoughts.

“I’ve been criticized the most for not writing good-guy/bad-guy characters,” Romero said, sipping his beer. “But my people aren’t clear-cut because real people aren’t clear-cut. They’re usually very gray, very ambiguous.

“That’s what makes this story so disturbing, because you don’t know where you stand with everyone. There’s a wonderful line in the original novel — ‘the devil is instinct.’ And I think that’s what I responded to most — the theme of the evil within, the Jekyll-and-Hyde quality of the character.”

For Romero, it’s hardly a leap to portray a modern-day character as possessed by rage. “I think we all have it inside us--and with some of us, it just comes out. I think people who have the most volatile tempers are often the healthiest because they blow it all off.”

Does Romero fall into that category? “No, I have a very high tolerance level,” he said. “In relationships, I’ll keep going and going and I’ll bend and bend and . . . suddenly one day I’ll just say. . . .”

Romero bellowed an obscenity. “Then I’ll slam the door and the relationship will be over--for good.”

The burly film maker grinned. “Maybe it’s healthy that I have my zombies. I can have them handle all that stuff for me and get it out that way.”

John Carpenter, a stellar horror director in his own right (his credits include “Halloween” and “The Thing”), is a longtime Romero fan--and friend.

“George is a great director because he’s never got caught up in all this Hollywood nonsense,” he said. “He’s been true to himself. What makes him so original is that he comes from a different place--his films have a totally different rhythm than most pictures you see.”

He’s trying to upset you, to change your perceptions, to shake people out of their complacency. George wants to grab you by the lapel and say, ‘Wake up!’

— John Carpenter

So why has Romero, like many horror directors, been so unappreciated? “Because most people think horror films are just one step above pornography,” Carpenter said. “People look at George’s audience as being the nuts on Hollywood Boulevard who yell and scream and throw popcorn when the zombies are eating someone’s shoulder.

“His movies are really strong stuff--but that’s what makes them great. He’s trying to upset you, to change your perceptions, to shake people out of their complacency. George wants to grab you by the lapel and say, ‘Wake up! Stop watching David Sheehan on Channel 4. Get out there and see real life!’ ”

For this film, Romero swapped his zombies for a fascinating collection of capuchin monkeys, who were on loan from Helping Hands, a Boston-based organization that trains primates to work with the disabled. (With characteristically sly humor, Romero gave his lead monkey, who starred in the vast majority of the shots, the stage name of “Boo.”)

“The monkeys were absolutely incredible to be around,” he said. “If you put a monkey in this restaurant right now, he’d immediately stratify the room. He’d decide who fit where in the hierarchy.”

Training the monkeys posed a considerable challenge. Super-agent Michael Ovitz could have never packaged this film — Romero cast Boo and his pals five months before choosing their human counterparts. “Boo was perfect for the role — she has such a Toshiro Mifune face that you actually can see the wheels turning when she thinks,” he said.

Still, it wasn’t easy teaching Boo — normally an amiable creature — to be aggressive.

“Boo would normally assume a very docile position around humans,” Romero explained. “But if a monkey thinks he can dominate you — if he thinks you belong below him in the hierarchy — then he will be much more aggressive.

“Boo once had a run-in with one of our assistant trainers and when he flinched, Boo got the idea that she could dominate him. So she’d puff herself and glare at him — in effect, sending him very menacing visual messages.

“It was just a posture, but we were able to use it. When we needed a shot of her looking angry, we’d bring in the same trainer and all get on his case. It’s a very tribal process — we’d each make menacing gestures and Boo would follow our lead.”

An equally difficult chore for Romero was filming the “love scenes” that establish the growing tenderness between Boo and lead actor Jason Beghe. “We shot those scenes when Boo was in heat. Our problem was that Boo would attach herself to whoever she first saw that morning. If her first contact was with the key grip, we’d be in trouble because she’d court him all day. So early in the morning, Jason would go over to the motel where Boo lived with her trainer and then come to the set together, just like real lovers.”

Romero admits to a tug of envy and admiration when he analyzes the primate world. “If you look at the animal kingdom, I think you see what you’d really want to be,” he said, working on another beer.

“I find myself thinking--’What are we doing to ourselves in our society? Wouldn’t we rather sleep all day and just get up to eat?’ It makes you wonder — are we gods or are we critters?”

Romero waved a hand in the air, showing a tiny shaft of air between his thumb and index finger. “That’s the difference. I think we’re critters — we’re just that tiny amount smarter than the next level below us.”

Romero would probably reserve an even lower rung of the evolutionary scale for marketing execs who make key editing decisions based on the reaction of recruited test audiences.

“That whole preview process is very disturbing to me,” he said. “I think it’s crazy to make choices based on how some focus group has reacted. Imagine if you were an architect who’s been building a house for someone. Suddenly some new person walks in — after you’ve almost finished the house — and says, ‘I want a bathroom here . . . and a window over here. . . .’ ”

Romero shrugged — he’s obviously fought this battle before. “Preview audiences will say the most amazing things. I mean, what if they like Darth Vader more than Luke Skywalker because he’s a more interesting character? Does that mean you’re supposed to chop up ‘Star Wars’ until people like Luke Skywalker the best?”

Judging from the edgy tone of his voice, Romero has been on the losing end of that argument. And he acknowledged that he changed the ending of “Monkey Shines,” at the insistence of Orion Pictures, his film’s distributor.

Romero’s original ending was considerably less optimistic — it implied the film’s evil forces were still at work. “I thought my ending played well, but I’d admit that the testing results were overwhelmingly in favor of the current version. To Orion’s credit, they said — it’s up to you, we’ll release it either way. So I decided to go along and not fight it.”

He grinned. “But I’ll always miss it.”

These kind of skirmishes have prompted Romero to remain in Pittsburgh, far from the chilly executive suites of Hollywood. Scarcely concealing his glee, he speculated that a proposed final installment of his “Living Dead” series might be a spoof set in Beverly Hills, where his zombies surround the local mansions, kept at bay only by huge armies of household servants.

“You have to be very thick-skinned and tenacious to survive in this business,” he said. “So I try to stay far away from all of it, out in the middle of the country. There’s a lot less scrutiny--nobody ever shows up on my sets.”

He unleashed a booming peal of laughter. “I always imagine the studio execs saying, ‘Where’s he shooting? Pittsburgh? Forget it!’ ”

Horror movies’ very neglect has allowed Romero a similar freedom from close scrutiny.

“They’ll always fascinate me because they provoke hidden emotions — emotions you don’t even know are there. In fact, I think horror films evoke as much surprise as fear, because even as you try to suppress the response, something in the film brings it out against your will.”

Romero beamed. “Maybe that’s what makes horror movies so scary — because we’re very unnerved by what we’ve discovered.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >> »

MORE ON ROMERO:

George A. Romero, ‘Night of the Living Dead’ creator, dies at 77 »

George Romero’s undead reckoning »

George Romero, knight of the living dead, is a zombie specialist »

George Romero dismisses ‘The Walking Dead’ as ‘soap opera’ »

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.