From the Archives: Garry Marshall followed his heart when he opened Falcon Theatre

- Share via

Writer-director Garry Marshall, whose TV hits included “Happy Days” and ‘’Laverne & Shirley” along with such box-office successes as “Pretty Woman” and “Runaway Bride,” died Tuesday. He was 81. Here is a 1999 Times article when he launched the first full season at his Burbank theater.

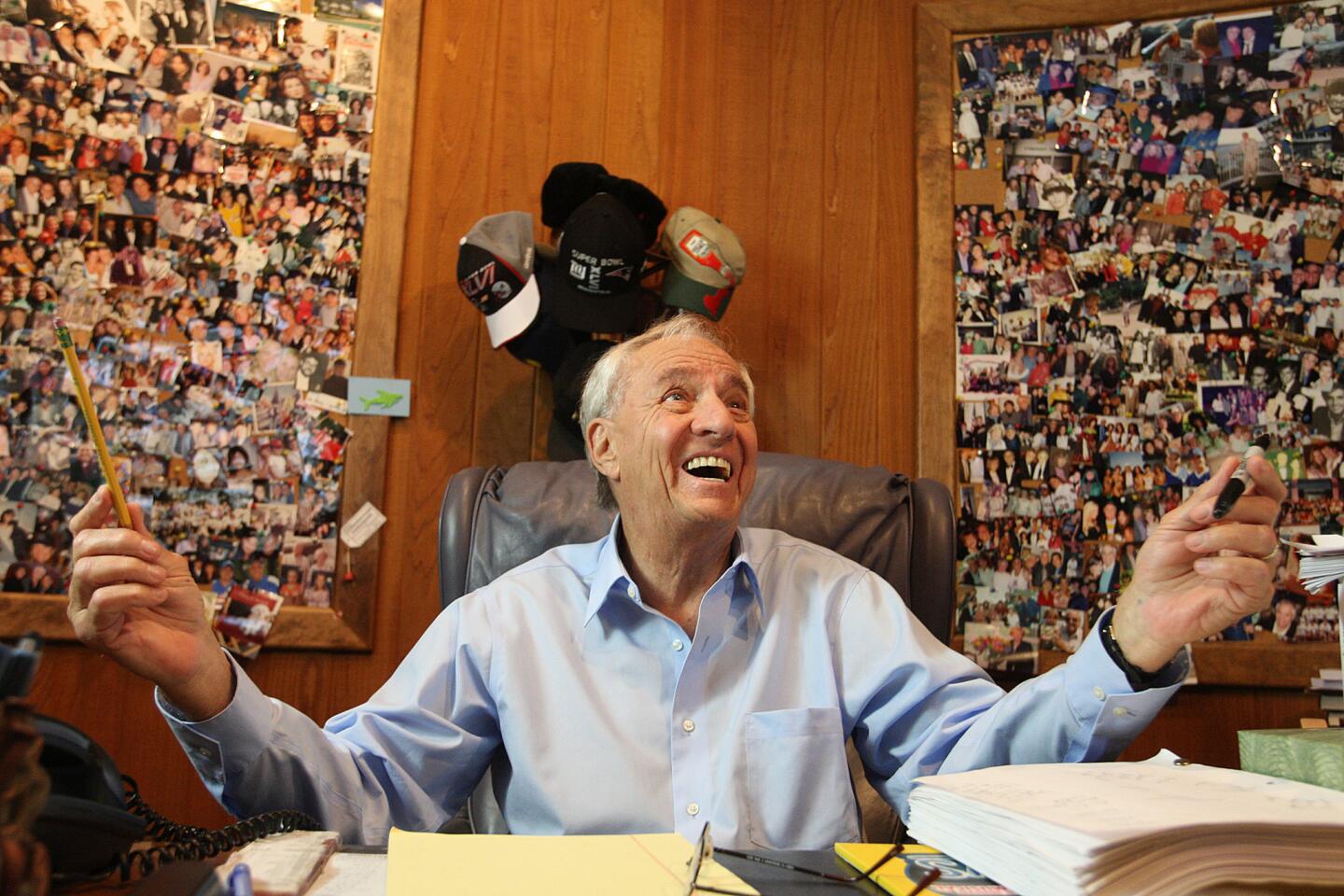

Posters and stills from some of his movies --”Pretty Woman,” “Frankie and Johnny,” “The Other Sister,” “Nothing in Common” — hang in the reception area. Another wall is covered with huge blowups from his landmark TV shows: “The Odd Couple,” “Happy Days,” “Laverne & Shirley,” “Mork & Mindy.” And a high shelf is filled with memorabilia from the same sitcoms.

In some ways, it’s exactly what you’d expect to find outside the office of a man who’s had as big a show-biz career as Garry Marshall. Yet in other ways, it’s not. Despite the display, the place has an undeniably homey feel. There is no Modernist designer decor, no show-biz glitz. In truth, it feels more like you’ve walked into someone’s den or living room--the kind of place where you might comfortably watch a syndicated rerun of a late 1970s series, or pop in a video of, say, “Beaches” with Bette Midler and Barbara Hershey, or “Overboard” with Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell.

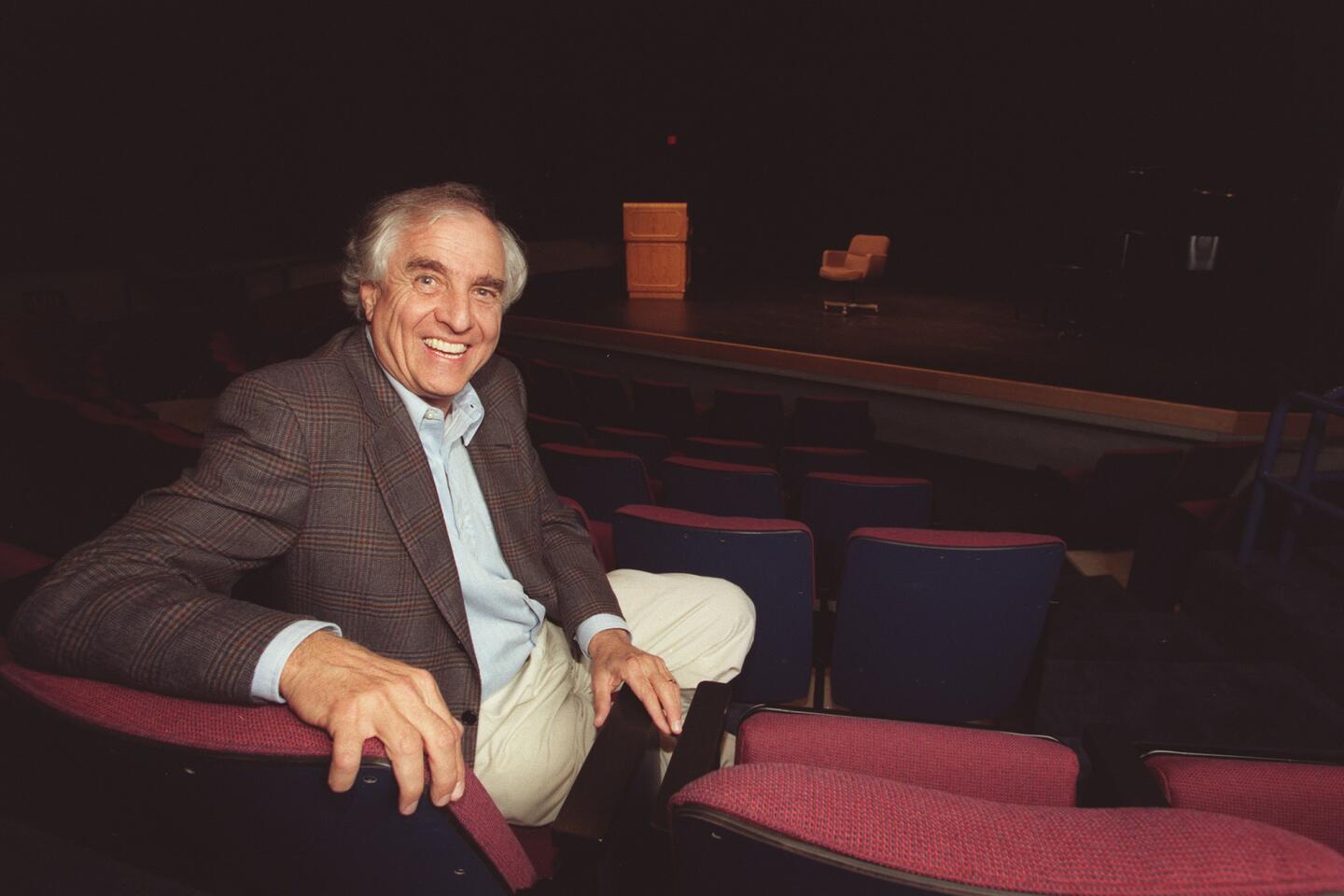

Outside, the cozy two-story Burbank complex has a wood and stucco exterior vaguely reminiscent of a Solvang shopping mall or a Woodland Hills condominium. Only the marquee announces it as the home of Marshall’s Falcon Theatre, which is about to open its inaugural season Wednesday with Beth Henley’s “Crimes of the Heart,” directed by Marshall and starring Faith Ford, Stephanie Niznik, Crystal Bernard and Morgan Fairchild. (The Falcon is also presenting a children’s play, Lois Lowry’s “Anastasia Krupnick,” adapted and directed by Falcon executive producer Meryl Friedman, on weekend afternoons.)

Surely the ambience of the place is no accident, for it’s in keeping with Marshall’s famously unpretentious persona. Affable, charming and known for his generosity, Marshall is the kind of guy who will inquire about a visiting journalist’s social life--”So, you’re married now? Seeing someone? You’ll let me know how it turns out”--and actually appear interested in the answer. It’s not hard to understand why he’s had such success with feel-good funny TV and, more recently, chick flicks, including the recent “Runaway Bride.”

He is what you might call a ladies’ man, although not in the usual sense of the term.

“What got me to the dance, very honestly, other than comedy, is women,” says the tall and athletic Marshall, 64, seated in his characteristically unpretentious corner office, with its traditional-meets-family-room furnishings. “Women are my best fans. As we go into the millennium, the biggest thing I think happening is the evolving of women.

“Women are running all over the place and men are so confused, they don’t know what’s happening,” he continues. “The young don’t want to get married so much anymore. It’s a very complicated situation now. The family is changed. The women have evolved. The evolving has been great for me. The falling of the family has been sad.”

*

His facility with traditionally female fare is one reason Marshall chose “Crimes of the Heart” to kick off his 2-year-old theater’s first full season. The 1981 Pulitzer Prize-winning comedy features three sisters who have gathered in their Southern hometown to sort out their messed-up lives as they await news about their dying father.

“I figured it was funny, it was cockeyed, and it had all the elements,” Marshall says. “I liked the fact that it’s about three sisters who are growing. People said, well, it’s just irrelevant now. Nonsense. One girl is abused, she’s getting smacked around by a guy--not something that’s gone away in 20 years. The other one is put down by her parents, so she has to get through that. And the other one is just a messed-up girl who made a comeback. And what I love is that they all bail each other out in a time of trouble.”

Yet if Marshall’s attraction to the Henley play makes sense, it’s less obvious why he’s directing a play in the first place. The answer to that lies in Marshall’s enduring affection for the stage.

Why bother directing a play at a 99-seat theater, even if it is an unusually elegant and sophisticated venue that you yourself had built? “Well, to me, life is all balance, and to go from a movie to theater is good for my balance,” says Marshall, whose “Pretty Woman,” starring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere, was one of the highest-grossing live-action films ever made by Disney Studios and who recently finished a publicity tour for “Runaway Bride,” which reunited the same stars.

“I love theater,” he says. “I thought I was going to go into theater. My mother dragged me to the theater. She always said that live entertainment is magic. She got it in my head that live was great.”

In fact, Marshall has been trying to go into theater for decades. “I’ve done three plays so far,” he says, referring to the plays he’s written or co-written over the past three decades. “All three indicated I was in the wrong field, but [that I] was getting better.”

A great believer in things superstitious, Marshall is quick to point out that a career on the boards has never seemed to be in the stars for him. “The director of my first play, the guy who was spearheading my play wonderfully, got murdered in Chicago. So it didn’t work out. The second play was called ‘The Roast.’ I loved it, a total failure. The third venture was [written] with Lowell Ganz, which was called “Wrong Turn at Lungfish.’ That didn’t do bad. It’s still out there, [published by] Samuel French, and it’s played around the world. Not a big smash, mind you, but it was a very good experience.

“He’s always loved theater,” confirms Jack Klugman, who starred in Marshall’s TV version of “The Odd Couple” and played the lead in the Falcon Theatre production of “Death of a Salesman” in fall 1998. “He knows that to do theater you’ve got to do your best work. It’s as high as you can go in our field.

“When he was directing ‘Lungfish’ in Chicago, he worked on it like it was ‘King Lear,’ ” Klugman adds. “His dedication shocked me. It reminded me of Voltaire writhing on the floor for three days trying to find the right word. You don’t do that in television. Growth is the name of the game in life as in art, and Garry loves to grow. Theater tests him.”

Family is also something that’s always been important to Marshall. Indeed, he’s famous for employing his relatives. He gave both of his sisters their start in show business. Penny began as an actress and became a film director. Ronny started out as a production assistant and became a producer.

Married to the former Barbara Sue Wells for more than 35 years now, Marshall is the father--and sometime employer--of two daughters and a son. His 1995 autobiography, “Wake Me When It’s Funny,” was written with his eldest, Lori. His middle child, Kathleen, is an actress who appeared in “Runaway Bride” and also supervised the building of the Falcon Theatre. And his youngest, Scott, is a director who frequently shoots the second-unit footage on his father’s films.

Born and raised in the Bronx, Marshall was plagued with illness and allergies as a child. But he always had a healthy funny bone.

“My mother taught us to be funny,” he recalls. “Dad taught us how to be the boss.” Marshall would go on to employ his father as a producer during his TV heyday. “He said, ‘Be a boss, don’t be a wimp.’ ”

Marshall studied journalism at Northwestern and, after a tour of duty in the Army, landed in New York. Working as a copy boy at the Daily News during the day, he began moonlighting as a joke writer for comics and others.

It was comedian Joey Bishop, in fact, who helped Marshall get a staff job writing for “The Jack Paar Show,” the precursor to “The Tonight Show.” Then, in 1961, when Bishop went to Hollywood to have his own late-night show, he brought Marshall out, too. Marshall then spent much of the early and mid-1960s writing sitcom scripts for “The Lucy Show,” “The Dick Van Dyke Show” and other popular series.

Marshall’s writing success evolved into producing, and by the 1970s he was riding high in the world of TV sitcoms. He went on to develop and create a total of 14 series, the most successful of which were “The Odd Couple” (1970-75), “Happy Days” (1974-84), “Laverne & Shirley” (1976-83) and “Mork & Mindy” (1978-82). During the late 1970s, his shows made up four of the five top-rated series then on the air, and he is credited with launching the careers of such stars as Robin Williams, Pam Dawber, Henry Winkler, Jason Alexander, Mayim Bialik, Crystal Bernard and many others.

In the 1980s, he moved over into directing film, with “The Flamingo Kid,” “Nothing in Common,” “Overboard” and “Beaches.” Marshall followed 1990’s “Pretty Woman” with such films as “Frankie and Johnny” and “Exit to Eden” and, more recently, “The Other Sister” and “Runaway Bride.”

His theater career has been a bit spottier. He wrote his first play, called “Shelves,” in the early 1960s. Inspired by his mother and set in his old stomping grounds of the Bronx, the piece painted a portrait of a housewife encountering the first onslaught of feminism. It wasn’t produced until 1978, when it was mounted at the Pheasant Run Playhouse in Chicago.

He co-wrote his second play, “The Roast,” with his then TV/film writing partner, Jerry Belson. About that time, Marshall also happened upon one of those signs he always looks for--the kind that tells you that you’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing. Staying at the Elysee Hotel in New York, he was rummaging for an errant bottle of Actifed. “I looked under the bed, and this is what I found, honest to goodness,” he says, retrieving an aged container from his briefcase. It is a bottle of Valium, prescribed for one Tennessee Williams, another man of the theater who used to stay at the Elysee. “I’ve kept this since 1981. I always use it when I direct. I thought it was a sign.”

It may well have been, for Marshall has done better in the theater since then. “Wrong Turn at Lungfish” premiered at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre in 1990. Marshall subsequently directed it at the Coronet Theater in L.A. in 1992 and at the Promenade Theatre in New York in 1993, starring George C. Scott.

And it wasn’t much of a leap from there to wanting to have a theater of his own. “I kept going to theaters, and you’ve got to get up sometimes in the middle of Chekhov and walk to the restroom, because the restroom’s in the back,” Marshall says. “I said, well, I’m not going into the theater business, but I figure I’d like a nice theater that’s got nice facilities, to give me a place to try out things.”

Last February, he hired Meryl Friedman to be the Falcon’s executive producer. The founder and producing director of Chicago’s Lifeline Theatre for more than 20 years, she came on board to run the Falcon’s day-to-day affairs, particularly when Marshall is off directing films. “Garry comes to the table with a different set of things than most theater producers,” she says. “This is not something he has to do. This is something that he wanted to do.”

“People keep asking what our mission is,” Marshall says. “I haven’t got a mission yet. My mission was to get people who wouldn’t otherwise do theater on that stage to do theater, and to find new [talent].”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.