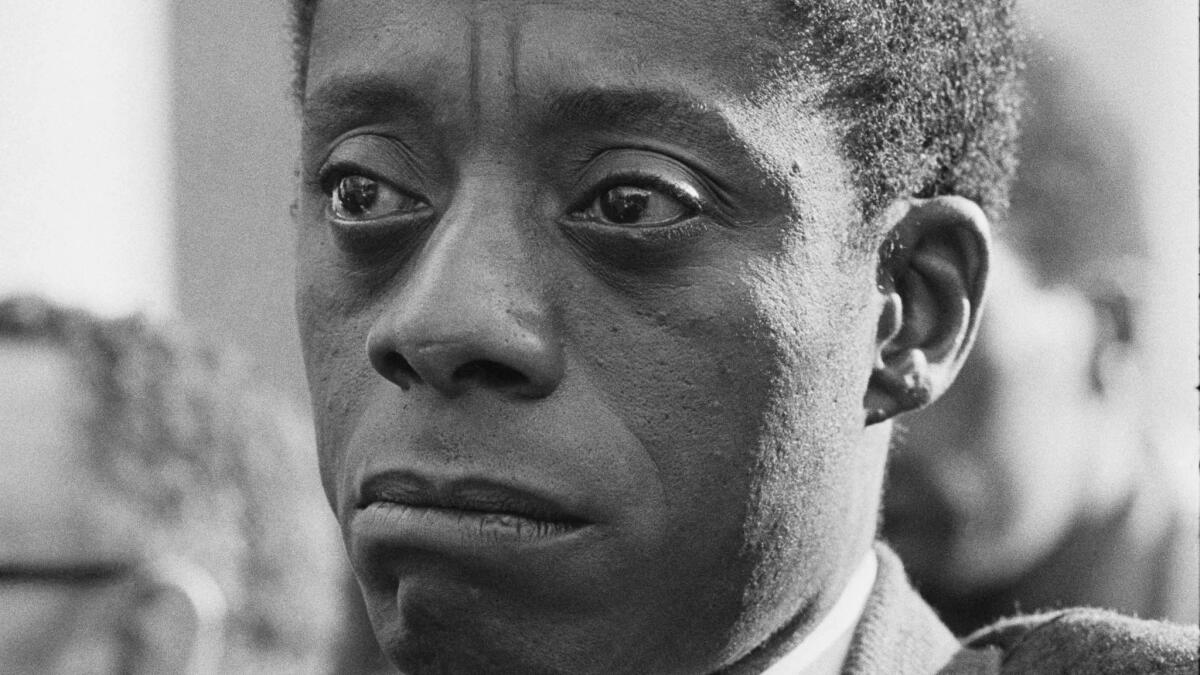

30 years after his death, James Baldwin is having a new pop culture moment

- Share via

Every writer hopes his prose will persist, but James Baldwin made an especially solid bet: As long as the disease of American racism, resentment of homosexuals, and the nation’s strange relationship with social class and capitalism lasted, his work, he knew, would matter.

But when Baldwin died 30 years ago, it would have been hard to predict that books such as “The Fire Next Time” — written as a letter to his nephew on the 100th anniversary of black emancipation — or “Giovanni’s Room” — a slender, once-obscure novel about a purportedly straight American and an Italian bartender who fall in love in Paris — would half a century later sit at the center of the zeitgeist. “Baldwin is back,” says Harvard literary critic and historian Henry Louis Gates. “Bigger and badder than ever.”

The African American author feels as central as he has since he landed on the cover of Time magazine in 1963, amid turmoil in Birmingham, Ala., for the “poignancy and abrasiveness” he brought to the nation’s “dark realities.” Some of this is because the energy of the Black Lives Matter movement recalls Baldwin’s own, and because the rising visibility of homosexuality over the last few decades made a resurgence likely if not inevitable.

But part of it is because Baldwin has stirred artists and writers in ways that no scribe of any color has done lately. Journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates — who’s become ubiquitous over the last two years — based his award-winning book, “Between the World and Me,” explicitly on Baldwin’s “Fire.”

The year’s best reviewed film, “Moonlight,” is not simply about characters — alienated gay black men — who resemble Baldwin’s heroes. It also has some of the writer’s sensibility. The film, like much of Baldwin’s work, feels as European as it does American: Its dark, oblique lyricism seems to come straight out of Michelangelo Antonioni or Ingmar Bergman.

But the debt to Baldwin is direct. “I describe ‘Moonlight’ as sort of the child of ‘Giovanni’s Room’ and ‘The Fire Next Time,’” says Barry Jenkins, the film’s director. “What I love about what Baldwin does is that the plot is important, but the emotions are much more what he’s about. That’s the way ‘Moonlight’ works too.”

The last few months have seen an explosion of work that either deliberately or subtly riffs on Baldwin’s life and work. In December, the eclectic and questing musician Meshell Ndegeocello brought her church-themed piece “Can I Get a Witness?,” based on “Fire,” to Harlem Stage. About a week later, Stew and the Negro Problem performed “Notes of a Native Song” — what the singer/ songwriter calls “just a bunch of songs with banter in between” — at REDCAT. (The show has played in a handful of other cities, including New York, where Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison attended.)

Most directly is “I Am Not Your Negro,” Raoul Peck’s Oscar-nominated documentary about both the writer and a project he never completed on the deaths of Malcolm X, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and civil rights activist Medgar Evers. We hear Baldwin’s words, spoken by Samuel L. Jackson, over footage of the Rodney King beating, over protests in Ferguson, Mo., and shots of young black men in prison.

So Baldwin is not just a writer for the ages, but a scribe whose work — as squarely as George Orwell’s — speaks directly to ours.

For a long time, the Harlem-born, France-dwelling Baldwin was an august figure in the literary world, but not one whose books were especially well read. (Ironically, Baldwin’s books, notably “The Fire Next Time” and the companion book of “I Am Not Your Negro” are both Amazon bestsellers.)

He was a kind of little brother in the holy trinity that also includes Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, both half a generation older. None of those figures was simple, but among them, Baldwin was the most idiosyncratic and, in part because he was openly gay and a European exile, one who seemed furthest from the center of the black arts movement and the larger “struggle.” The militant black writer Eldridge Cleaver, in his influential “Soul on Ice,” called Baldwin’s homosexuality a sickness and described him as a self-hating black man for his interest in white literary models.

Baldwin was hard for the liberal consensus or black establishment to embrace: He dismissed the Kennedys’ civil rights efforts, attacked the narrowness of mainstream black Christian culture, and sharply criticized Wright’s work. In “Native Song” Stew compares it to an aspiring young rapper put on the map by Kanye West suddenly turning on his mentor.

Baldwin admired many artists who weren’t African American, which did not endear him to the Black Panthers. He penned an insightful profile of Bergman (“The Northern Protestant”) for Esquire in the early ‘60s, and later wrote about his friendship with Norman Mailer. When Gates, as a young man, visited Baldwin in the South of France in the early ’70s, he was amazed to see a whole shelf of books by or about Henry James. “His prose was Jamesian,” the scholar says. “Henry James and the King James Bible. I’d just write down his sentences because I liked the sound of them.”

Often, though, he was buried by respectful neglect. It would have been easy to earn a robust literary or historical education in the 1980s or ‘90s and not read a single work of Baldwin’s. Partly, it was because his greatest achievements were with essays rather than novels, and because his irony and nuance could be difficult to hear over the straightforward rage of Wright’s “Black Boy” and “Native Son,” or the sheer brilliance of Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” Baldwin was, for a long time, out of fashion.

“Moonlight” director Jenkins studied black literature at Florida State University without reading Baldwin at all, and found “The Fire Next Time” only because a friend mentioned his work. “Giovanni’s Room,” he says, was “the first queer novel I ever read,” and one of the first black novels as well. “It was like two doors being kicked down at once.”

But between Coates and an anthology from August called “The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race,” which includes pieces by Claudia Rankine and Isabel Wilkerson, it’s been hard to miss his reemergence.

“Any time someone uses the term ‘Baldwinesque’ I think of shockingly articulate and flamboyant,” says Stew, whose band the Negro Problem — once a highlight of L.A.’s indie rock scene — took its name from a phrase Baldwin used ironically in “Notes of a Native Son.”

“We speak his language today,” Stew says. “We use his ideas to navigate the contemporary terrain. A guy can’t get any more relevant than that.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.