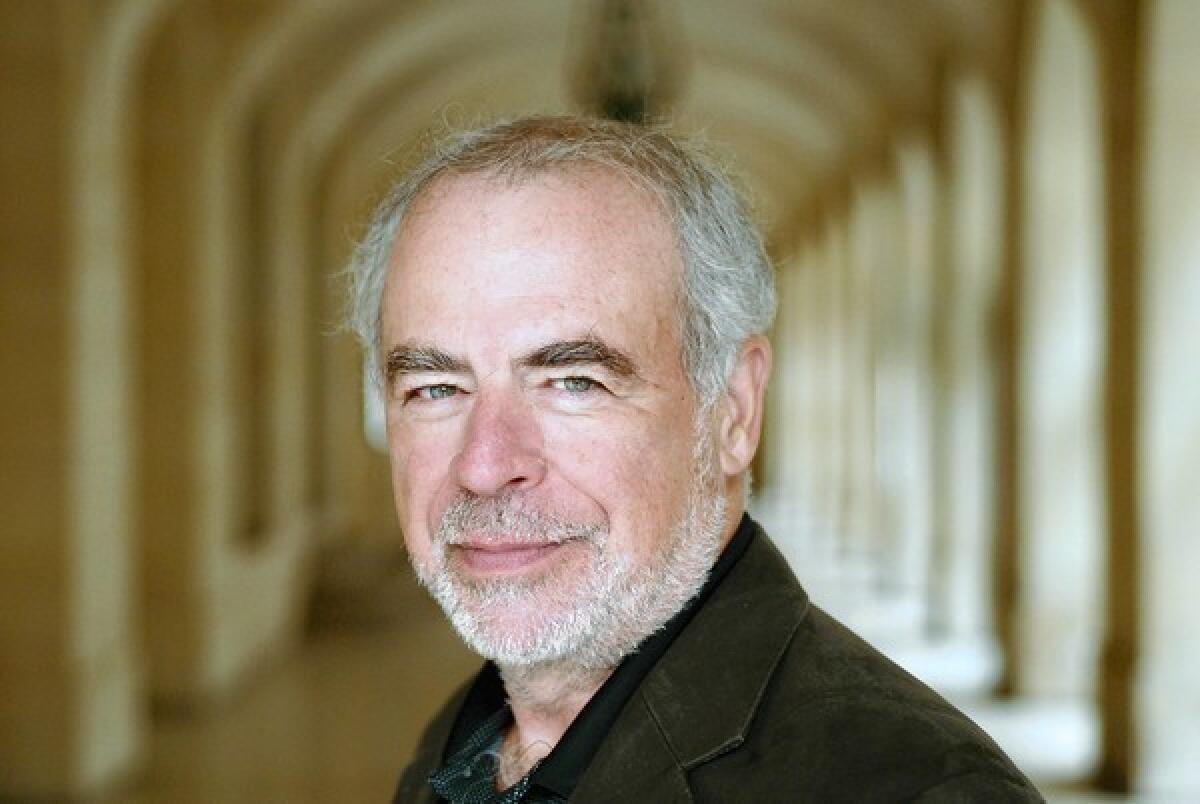

Richard Russo on family ties in new memoir

In his first memoir, âElsewhere,â Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Russo examines his intense relationship with his late mother, a woman whose strange behavior was explained by the family as a simple case of ânerves.â Russo talked about his new book from his home in Camden, Maine.

Why your first memoir now?

In a sense I would have preferred that it be never. Iâm a perfectly happy novelist. I love to invent things. But in the months after my motherâs death, which was about five years ago, she was very much on my mind and also visiting my dreams as well, which made it feel to me like maybe there was unfinished business there.

I think that this book is in a way connected to my novels, especially the last couple, because âEmpire Fallsâ and âBridge of Sighsâ are both about people who are pushing 60 pretty hard and wondering, how in the world did I come to be here? [In âEmpire Falls,] Miles Roby has this profound sense of his motherâs dream for him, and he imagines this other life where he is a learned man if only he had finished college the way she wanted him to and become some sort of teacher or professor, that he would have fulfilled her dream. In âBridge of Sighs,â Lucy Lynch, who never leaves his hometown, wonders, how is it that life turned out this way? What was it in my genetic makeup, what were the choices that I made?

And in the months after my motherâs death, I found myself puzzling over these questions of destiny, because we shared so many similarities, both of nature and nurture. Weâre both obsessive genetically, I think.

Why do you think her death gave you no closure, though, as you write in the book. Is it because you felt that you could never do enough for her?

I still had the feeling for many months after her death that I had failed her in some way. I had the sense of all sorts of things that Iâd forgotten to do. For all those years there was every day a list of things that needed to be done. And when she was gone, the items on the list disappeared, but not my sense of the list.

Did you feel it was your responsibility to make your mother happy, which she never really was?

Yes, I felt the weight of that. I felt that if she wasnât both happy and healthy â and healthy every bit as happy, because at a very early age, I felt that her health was in some way my responsibility... Weâre not talking about front-of-the-brain stuff, weâre talking about back of the brain. I mean Iâm not stupid. I know that nobody can make somebody else happy or healthy, but thatâs in the front of the brain. Thatâs what you know intellectually, which has really very little to do with that other part of the brain that you donât have control of.

I wondered whether there wasnât something about the intensity of this relationship that was peculiar to the fact that it was between a mother and son, especially since the mother is a single parent and the son a single child.

When youâre an only child and you have no one to compare notes with, everything seems normal. And for me, part of the experience of writing this book was not to tell people what I knew, but rather to tell them what I didnât know, what it was like growing up as a child with someone you sensed was in some way possessed.

After her death, you figured out that she had obsessive-compulsive disorder. Did you never think that her strange behavior rose to the level of mental illness before that? Didnât other people around you suggest that?

No. In the family, there was always the sense that the women in the family were ânervous.â That was the word that was used. I began to get the surest sense of it after Barbara and I married. And I began to get a sense from Barbaraâs parents and other people my mother met after we were adults that other people knew something was wrong.

In addition to your mother defining normal for you, was there something in you that resisted drawing that conclusion?

Absolutely. Because to draw that conclusion would be a betrayal. As her world grew more difficult and narrow and she became more afraid of things outside of her very restricted world, we began to suggest to her that it might be good for her to talk to somebody. But even in those most benign terms, she would just go off the deep end. Thatâs typical of OCD sufferers, because unlike other people with mental illness, they know perfectly well that thereâs something wrong and they know pretty much what it is. But they just canât face it.

For me, one of the other tricks of writing the book was to not let that leak into the book early because this is not a medical book, and because I want this to be something that people experience as opposed to something they become educated about.

I was surprised to see you admit in writing that if your wife hadnât been willing to help take care of your mother and you had to choose between them, you would have chosen your mother. How did your wife respond to that?

There was no reason to respond to the statement. She was responding to the truth on the ground. Because if Iâd been willing to turn my back on my mother and her demons, our married life would have been much different. And Barbara simply never forced me to make that decision.

Did you write the book to figure all this stuff out so you could make peace with your past?

In large measure, yes. I wrote this book the way I write all of my books: not to tell people what I think, but to discover what I think. Thereâs a way that if you write something down that isnât 100% true, youâre much more likely to recognize it than if you just say something. So the writing of this book was a way for me to do an investigation.

Why did you decide to publish it?

I decided to publish it only after I let my wife and daughters read it. And I let my aunt â her sister â read it. And my cousin Greg to whom the book is dedicated read it. Everybody whose opinion meant the most to me said that a lot of people are going to read this and be helped by it. But also it is a book that, despite how fraught our relationship was, makes clear how much I loved her. The very fact that I not only couldnât turn my back on her, but also at times my devotion to her and my gratitude for everything she did for me, in that cruel way that life sometimes manages to do, made me not only someone who provided for her in terms of the things that she needed, but also prevented me from providing for her the things that she needed most. I was, I came to understand, her enabler in many ways. So it was the story of what I did and also what I failed to do right straight through to the end. And people who blithely say that love is the answer arenât asking the question very clearly.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.