Appreciation: What I learned, forgot and relearned from George Martin, the master of the Beatles sound

- Share via

I was 7 years old the first time I read the word “producer” on an album. My parents, who owned mostly classical music LPs, had a handful of pop albums. They were all by the Beatles.

The album I listened to most was “Rubber Soul” because I liked the bit in “I’m Looking Through You” where a buzzing little guitar phrase appears right after the chorus. I didn’t know I was looking for louder guitars, or noise, or punk rock. And I didn’t know what a producer was. But there at the bottom of the back cover were the words “Produced by GEORGE MARTIN.” I figured he had something to do with that funny, nasty guitar sound.

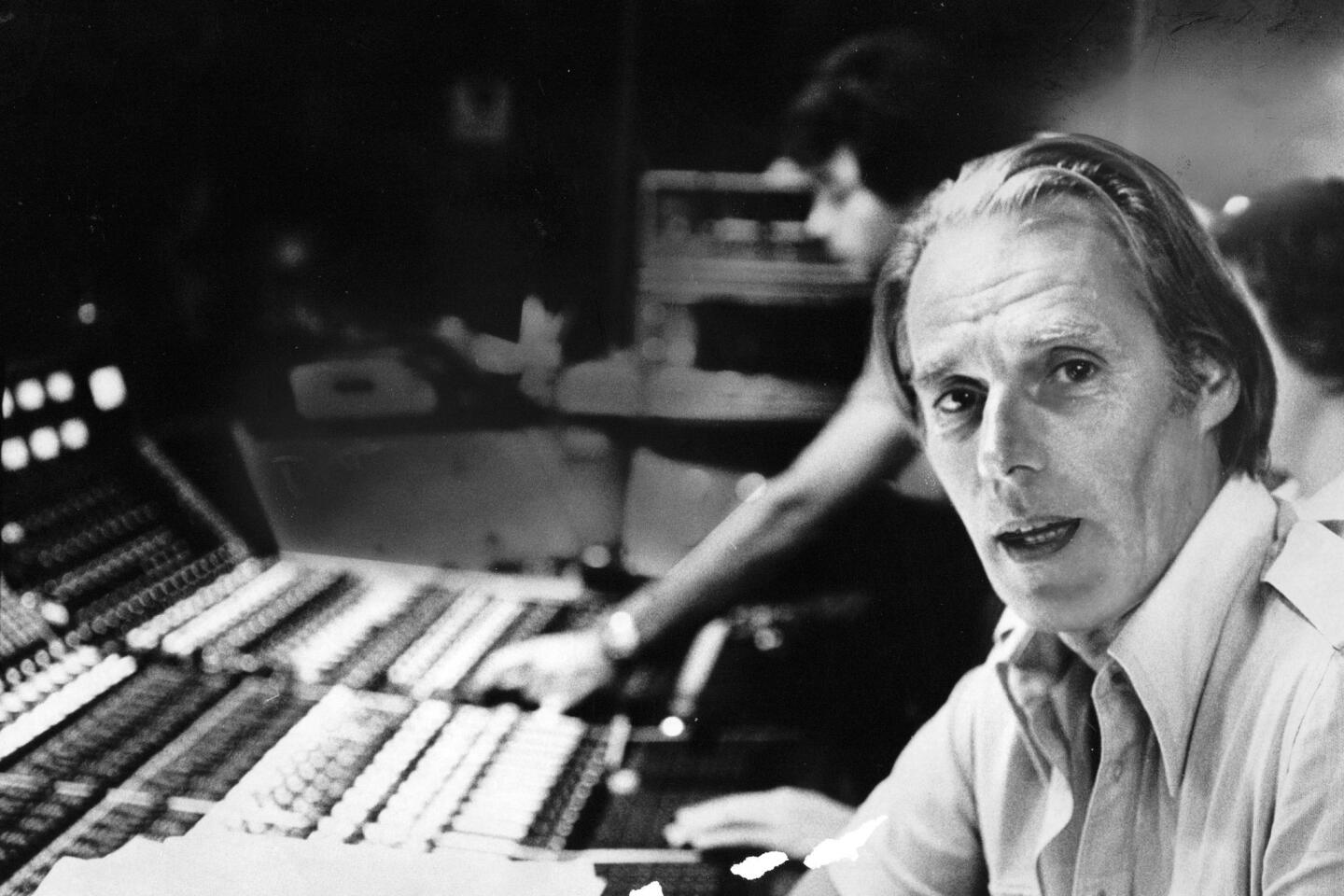

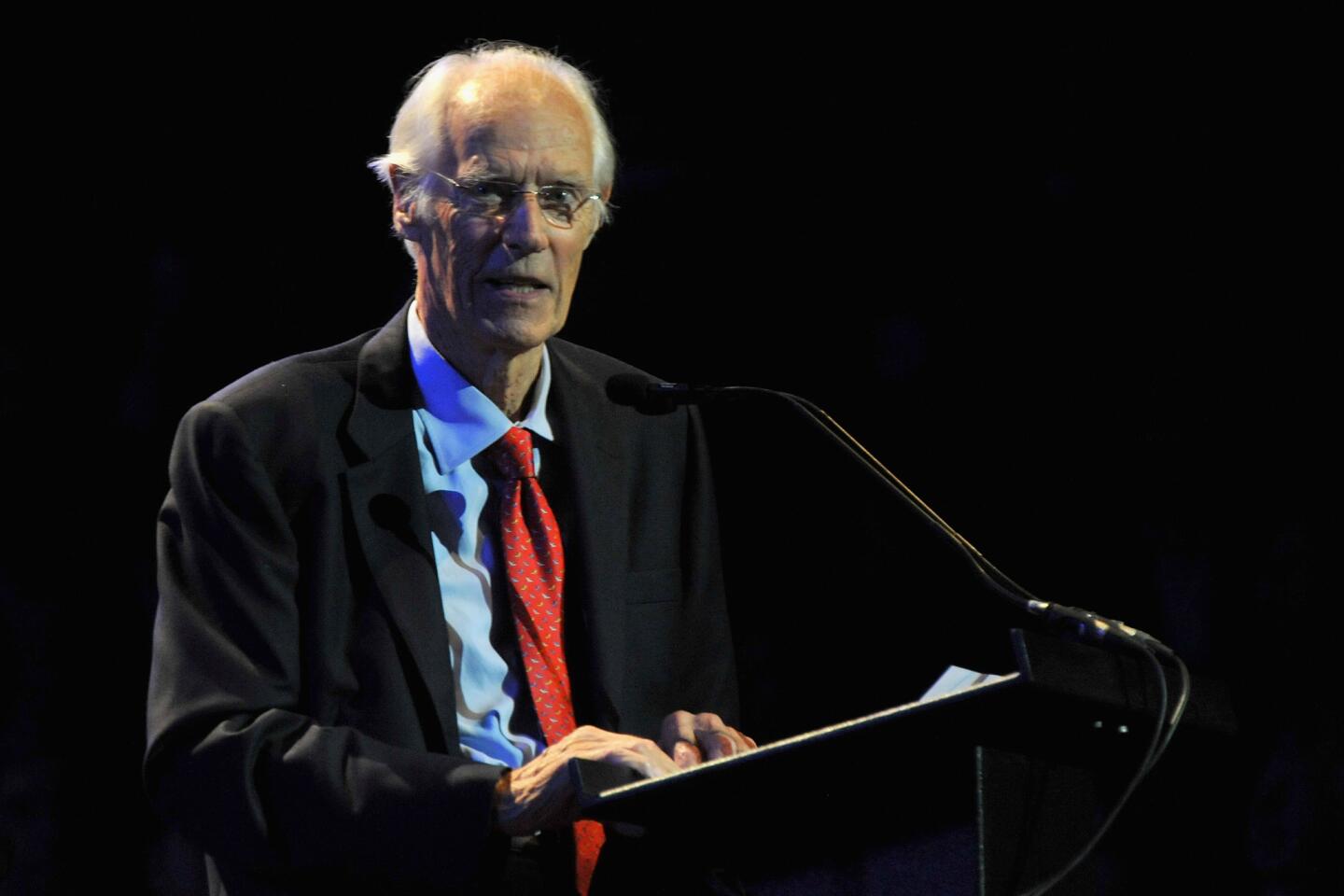

On Tuesday, George Martin died, at age 90. I’ve spent most of my life as a musician and a critic learning his work, forgetting his influence, avoiding him, relearning him and living in a world whose boundaries were his, for better and worse.

By the time I turned 21, I had already started my second band. We had just covered “Tomorrow Never Knows,” a Beatles song I will still play without complaint, though there are dozens I simply can’t because I’ve heard them so often I no longer recognize them as music. For my birthday, my parents gave me a newly published book by Mark Lewisohn called “The Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Abbey Road Studio Notes, 1962-1970.”

Like millions of other musicians after me, I read about all the tricks Martin, along with engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Townsend, employed on “Tomorrow Never Knows.” I was forever enlightened, puzzled and spoiled. There probably isn’t a rock band that hasn’t tried something stupid like swinging a microphone around someone while they sing or finding a Leslie cabinet — a box housing a speaker that rotates during playback — because they had the idea, loosely gleaned from Martin, that their unimpressive song would somehow get better if something was run through the Leslie and recorded on its own track.

The omnipresence of the Beatles and Martin’s imagination was liberating and, eventually, oppressing. As a child, it was my entry into pop music. As a young man in a band, Martin’s work shaped my approach to recording and led me to think of production as its own act, a process I could notice if I listened hard enough. Everything that had seemed natural to me in recordings became suspect, not in a bad way, but in the way that Santa Claus is not real but it’s still awfully nice that your parents bought you GI Joe with kung-fu grip. I would listen to recordings and try to figure out if something had been double-tracked or added after the fact.

As I came of age inside the independent rock community in the late ‘80, there was a revolt against the sumptuous production values Martin and the Beatles enjoyed at Abbey Road. Recording songs live, fast and raw became its own virtue, which ironically mirrored the Beatles’ early days, playing night after night in Hamburg and recording songs in single takes with no overdubs.

The Beatles are very hard to escape if you get it into your head that you are going to be in a band and go into a recording studio.

Martin’s innovations become sort of a Steph Curry situation for people making multitrack recordings. At a certain point, when you haven’t been able to conjure the perfectly liquid bass sound and beautifully altered vocal harmonies, Martin and his friends are no longer geniuses — they are your demons, your Mozart, your Voldemort.

No, you think, they can’t have been that good. It was all that free studio time. It was just a perfect storm. And if you listen to enough solo Beatles albums you can talk yourself out of believing in them. It became cool, after all, to hate the Beatles. There was a rumor that, after Pussy Galore had covered all of the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street,” Sonic Youth was going cover the Beatles “white” album, as sort of an Oedipal act. As Sonic Youth themselves wrote, “Kill Yr Idols.”

Which is what happens when you finally go back to the Beatles albums. You can easily make the case that too many people have thought too much about what Martin and the Beatles achieved and not enough about, say, what Sly and Robbie did with Grace Jones. But unfortunately, Martin’s work with the Beatles remains as uncanny and vivid as conventional wisdom holds it to be.

Even “simple” tracks like “No Reply” are nested eggs of perfect decisions in arrangement and mixing. Ringo Starr is a gentle presence until Lennon and McCartney sing “lie” together in the chorus — suddenly Starr’s crash cymbal is enormous and frightening. The betrayal at the heart of the carefree song surges into view, and, hang on, there’s a huge piano chord in here somewhere — was there always a piano in this song?

The Beatles are obviously the Beatles, and that certainly lifts your chances of becoming George Martin. But, then, would the Beatles be the Beatles if someone hadn’t been there to turn the acrimonious songs into bossa nova Trojan horses, or turn Lennon’s dissociative language into fairground anthems and backward bird sounds?

You don’t even have to end up liking the Beatles. Pick a song on any album and turn everything else off. “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” — that still sounds so revved up, unnaturally alive.

Oh, they sped the tape up slightly during mix down. Thanks, George.

MORE ON GEORGE MARTIN

Listen to 10 George Martin tunes that go beyond the Beatles

Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and Sean Ono Lennon remember Beatles producer George Martin

George Martin’s indispensable role with the Beatles

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.