From the Archives: Carrie Fisher: Over the edge and back in her first novel

- Share via

Actress and author Carrie Fisher, the child of two Hollywood icons who rose to fame as Princess Leia in the blockbuster “Star Wars” series, has died at age 60. Fisher talked to then-Times staff writer Nikki Finke about image and addiction after the publication of her first novel “Postcards From the Edge” in 1987. This story originally ran in the Los Angeles Times on July 31, 1987:

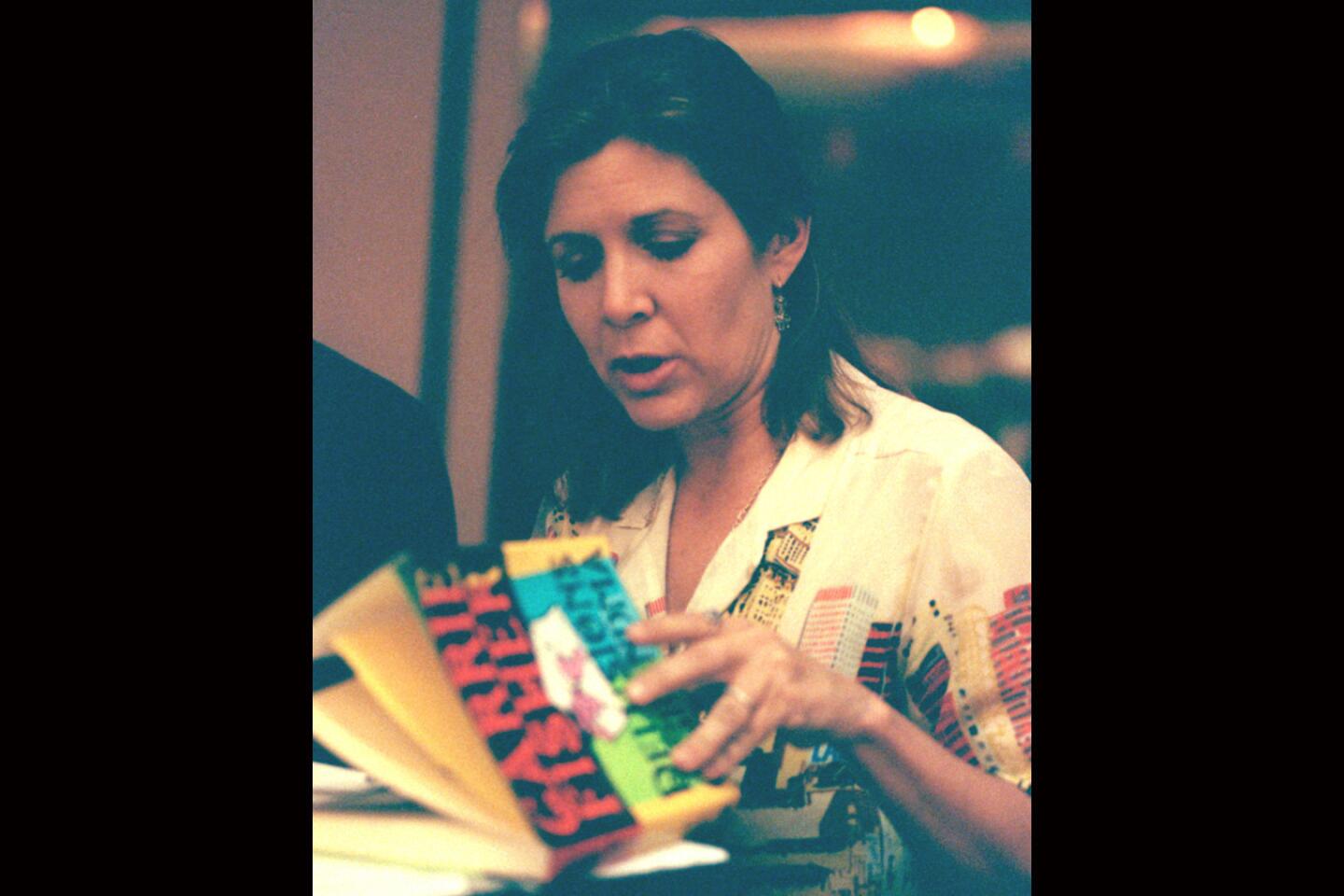

The photographer scouting locations stops in front of a beer stall in the center of the Farmers Market. Would Carrie Fisher mind posing on a bar stool? Or would that be, uh, bad for her image?

“Bad for my image?” the 30-year-old actress-turned-author echoes incredulously, her voice so loud that everyone standing or sitting nearby starts to stare. “I wrote a partly biographical book about my drug addiction that starts out, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t have given the guy who pumped my stomach my phone number,’ and you’re worried about my image? There is not one area of sensationalism that I have not wandered into and trespassed wildly.”

Fisher is currently invading bookstores with her first novel, “Postcards From the Edge” — which she affectionately refers to as “Gidget Goes to Hell” — a bitingly clever roman a clef based on her own not-so-distant past trips through not only drug clinics, but movies, therapy and relationships as well.

A single woman’s answer to Nora Ephron’s “Heartburn,” a less sexual version of Erica Jong’s “Fear of Flying,” the smart successor to Joan Didion’s “Play It as It Lays,” Fisher’s novel would be interesting even if someone else had written it.

But considering that the author is the pre-Liz product of that fabulous ‘50s couple Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, the personification of Princess Leia from the “Star Wars” trilogy, the ex-wife of music superstar Paul Simon and the latest in a long list of celebrities to publicly confess a drug problem, the book takes on added significance because it’s a Hollywood insider’s look at what Fisher disparagingly labels “what it’s like to live an all-too-exciting life for all too long.”

“When you’re brought up in a certain luxury, you also have the luxury of neurosis. In my case, there was a certain level of torment that fails articulation,” she adds.

At the Farmers Market, a place she has chosen “because these are the real people--at least I think they are,” Fisher is chagrined at herself for buying cigarettes even though she ostensibly quit some time ago. It takes her at least six matches to light each one because the very second a match starts to flame, she puts it out.

While her hands are engaged in this ritualistic dance, her conversation is weaving as wildly as the ambulance that careened down the freeway and rushed her to the emergency room at Cedars Sinai Medical Center for a drug overdose two years ago. “Getting my stomach pumped was my bottom,” she recalls of her four years of addiction. “So I’m lying there and I’m thinking, ‘I don’t like this. I don’t want to do drugs anymore.’ ”

It’s a real-life example of her favorite saying, “good anecdote, bad reality.” And ultimately great material for her book. Like her fictional alter ego, Suzanne Vale, Fisher relies on comedic relief to make any emotional trauma more bearable. “I have a colorful way of expressing brown or gray depressions,” Fisher says. “It sort of keeps me away from myself.”

At times, this diminutive star--who can look childlike sipping her fourth Diet Coke through a straw--seems to be all 5-foot-1 of matured mouth. In truth, she is much funnier in person than she has ever been on the screen as she describes her self-obsessed, much-analyzed, over-envied life “growing up as a famous child but just wanting to be normal. I feel like I’ve been detained in psychoanalysis for an inordinate amount of time. I have to call my lawyer and arrange bail.”

A writer of admittedly “pretentious” poetry from childhood through puberty (Her example: “My nose runs. My mind follows.”), Fisher as an adult became famous within her circle of intimates for sending out the most outrageous postcards, hence the name of her novel. “Some, of course, are quite dirty,” warns screenwriter Buck Henry, her friend and mentor. “But I’d be willing to buy her a ticket anyplace just to get more. She has a love-hate relationship with everything--starting with herself.”

And what she hates about herself most is her inability to keep her thought processes under control. “It starts right away in the morning as soon as I wake up,” she explains as she digs into a plate of refried beans between cigarettes and Diet Cokes. “I get a feeling like my mind’s been having a party all night long and I’m the last person to arrive and now I have to clean up the mess.” The result, she says, is that “I think with my mouth.”

‘Ultimate Cliche’

Suddenly, she darts into a newsstand to grab the latest issue of Vogue and see what damage her latest verbal volcano about her drug addiction has caused. “I am the ultimate cliche of all time--the celebrity who goes into a drug clinic,” she says, shaking her head morosely as she flips through the pages. “That’s why I don’t even like talking about it. And yet I do and then I read it and I think, ‘Oy, shut up already.’ ”

She’s so eager to please everyone that she answers every question, signs every autograph, performs upon request. In fact, after her book tour kicks off in August, she is thinking of sending all her interviews to her therapist with a note saying, “Know you’re wondering how I am. Read these.”

Indeed, she chose not to do her drug rehabilitation with the other celebs at the Betty Ford Clinic “because I didn’t want to be a People cover.” She ended up for 37 days, three hours and two minutes at Century City Hospital’s New Beginnings program where “I felt most happy with all the weirdness.” When people in the program would confess that they’d been in San Quentin, Fisher would respond, “I was in ‘Star Wars.’ ”

Prescription barbiturates like Percodan, Valium and Dalmane were her drugs of choice, not stimulants like cocaine. “Well, look at my personality,” she explains. “It always felt to me like I was too much . And even though I was brought up in a show-business situation where sticking out is OK, I felt like I was jutting out.”

The drugs did more than just smooth down her edges. Recalls Henry: “She would go to sleep in mid-sentence. Or she would go to bed for a week at a time.”

Publicity’s Child

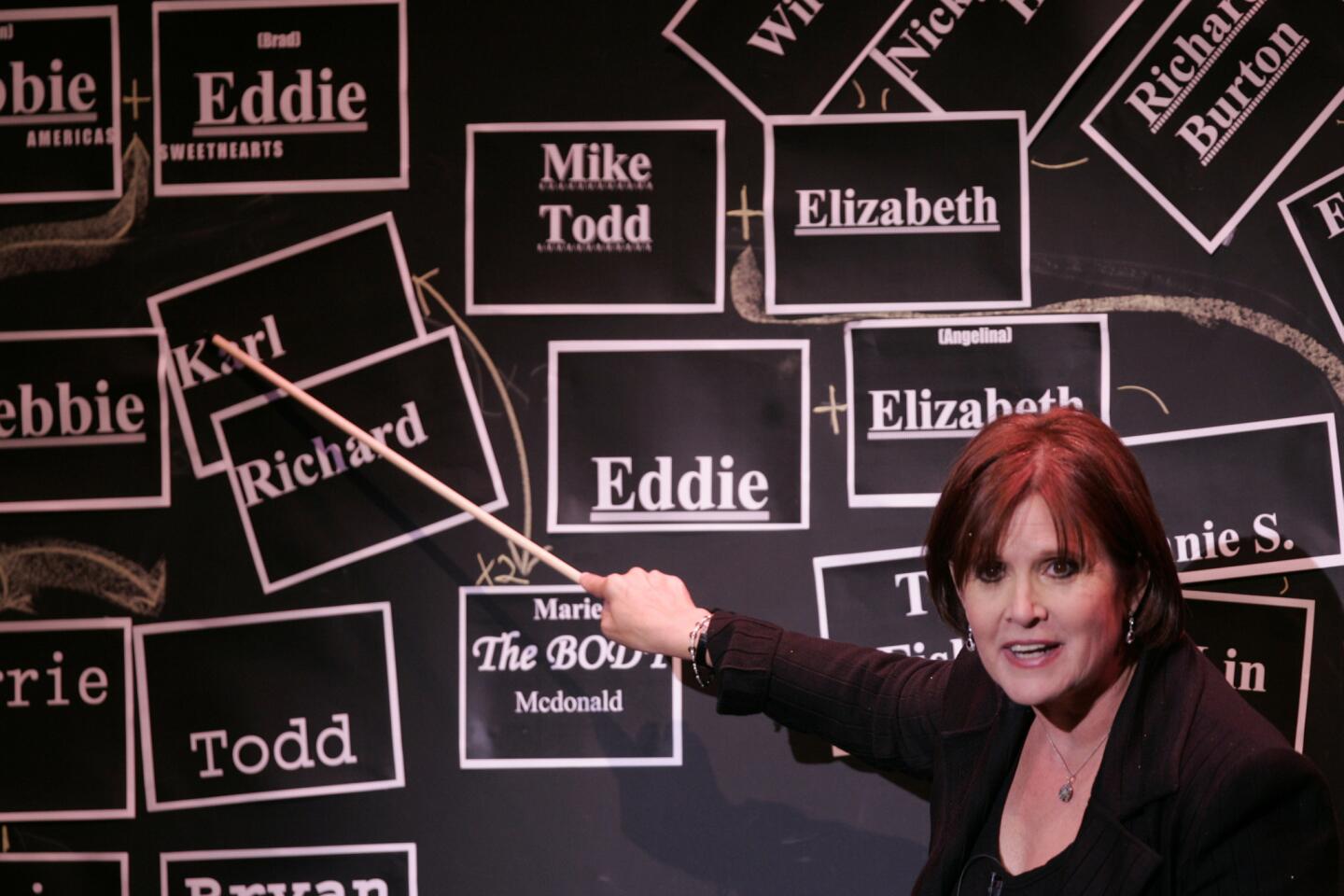

Where did things go wrong? She doesn’t really blame her much-publicized childhood for her adult unhappiness, even though everyone knows that she was just 18 months old when her father left her mother for Elizabeth Taylor. “I’ve always said that if I wasn’t Debbie Reynolds’ daughter, I’d make fun of whoever was,” she quips.

Now she feels that journalists want to read too much into the fact she dedicated her book only to her mother and brother, or that her alter ego has trouble with relationships because she didn’t grow up around her father. To make her father feel better after he read several overreaching magazine interviews she gave, “I had to say to him, ‘No, Dad, I said I blamed Eddie Cantor.’ ”

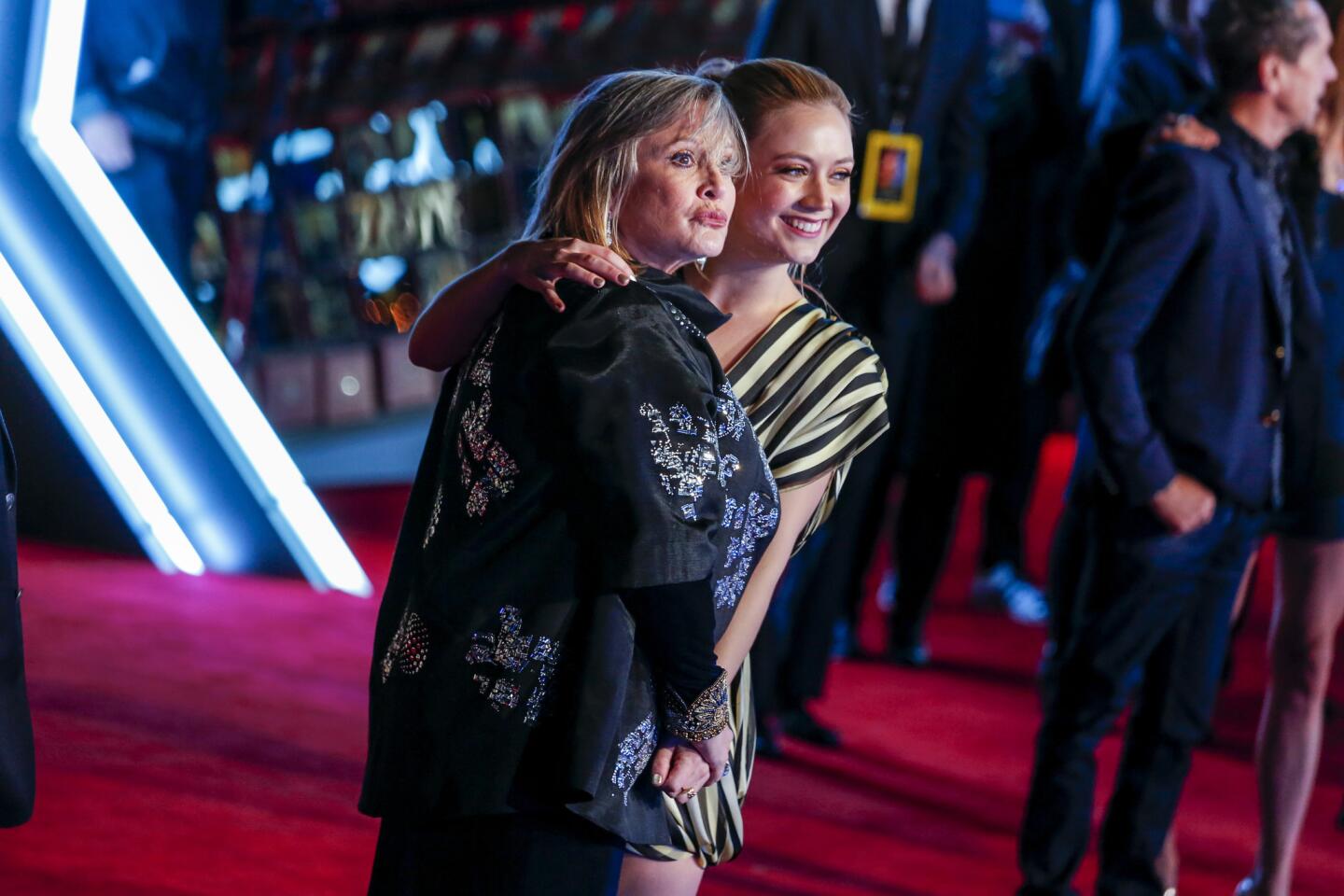

Even her mother, Debbie Reynolds, admits feeling angered “when some publicity first came out that was very inappropriate. Had she not had famous parents, Carrie would not have been subjected to that. But it’s been a cross to bear for both of my children.”

Reynolds, reached in Reno where she is appearing at Harrah’s, was quick to confirm a line in “Postcards From the Edge” in which Suzanne’s mother assures her daughter that “you were happy as a child. I can prove it. I have films.” In real life, Reynolds says, she has 48 hours of Bell-and- Howell footage on her children. “Since fathers didn’t work out well in our family, it was left up to me to film them.”

A Career Prediction

Reynolds, for one, believes her daughter has found her real metier. “I don’t want to sound like a mother,” she says, “but I think in a market full of literature Carrie stands out as a very quotable writer. She has done very well as an actress, but I think her literary career has just begun.”

But can she start fresh in a town where she is so well known? Fisher thinks she can. “L.A. never made me crazy, even if a certain part of me is horrified that I could grow up here.” Perhaps that’s why she lives unconventionally in the Hollywood Hills in a log cabin that was once part of a 1930s Fox studio set. With her dog, talking parrot and backyard porcelain cow as well as a sign warning visitors about “frilled neck lizards,” Fisher’s residence is the purest reflection of its owner’s penchant for whimsy, especially the life-size cutouts of Snow White’s Seven Dwarfs on the stairway and a brass gate plate that reads, “Wow! That Was Some Cup of Coffee Institute of Alternative Life-Styles.”

Even after dropping out of Beverly Hills High School to dance in the chorus of her mother’s Broadway hit musical “Irene” at age 15, propositioning Warren Beatty in “Shampoo” as a wiser-than-her-years nymphet of 17 and maturing before audiences’ eyes as Princess Leia from 19 to 26, Fisher still professes to feel like a Hollywood outsider. “I don’t dress right. I don’t look right. I don’t embrace the values of the community. And yet it always seems to me that the other people function better.”

So, as a defense mechanism, Fisher began finding fault with Hollywood before it could find fault with her. Her book articulates her feelings about the industry and its people. “You can’t find any true closeness in Hollywood,” she writes, “because everybody does the fake closeness so well.”

Dating Dilemma

Fisher finds meeting men especially hard, which is why she refers to it as “terrible, terrible dating accidents. Celebrities can’t cruise men. It’s a rule I made up,” she says. “What am I gonna do--go up to someone I think is cute and say, ‘By the way, I was Princess Leia?’ ” She also doesn’t think celebs should date celebs, even though they’re the only ones she meets. That’s why she thinks her divorce from Paul Simon was inevitable after 11 months of marriage. “We are two volatile personalities,” she explains, trying to light yet another cigarette.

By now, nearly the entire Farmers Market has been listening to Fisher’s musings because her voice literally booms. “I know women aren’t supposed to be so verbal and loud. But I’ll get back to you on everything else,” she quips. While other people just accept themselves for what they are, Fisher fixates on her every real or imagined failure--from the new pimple on her chin to the way she says she can “make $300 dresses look like something you buy in a Kuala Lumpur market.”

No stranger to the self-destructive tendencies of other celebrities (John Belushi was a good friend), Fisher feels she has found the perfect form of therapy for “people who dare to be pathetic.” Noting that “instant gratification takes too long,” she says she now grabs a legal pad instead of pills.

She never thought of writing seriously until she gave a hilarious interview to Esquire writer Paul Slansky in 1985 on subjects ranging from her favorite bumper sticker (“Love Is the Liberace Museum”) to the difference between New York and L.A. (three hours). Crown Books immediately wanted her to write a book of essays about the world according to Carrie. “It was supposed to be Fran Lebowitz in Hollywood. They wanted my take on certain things,” Fisher says. The working title was “Money Dearest” and Slansky was hired to help her.

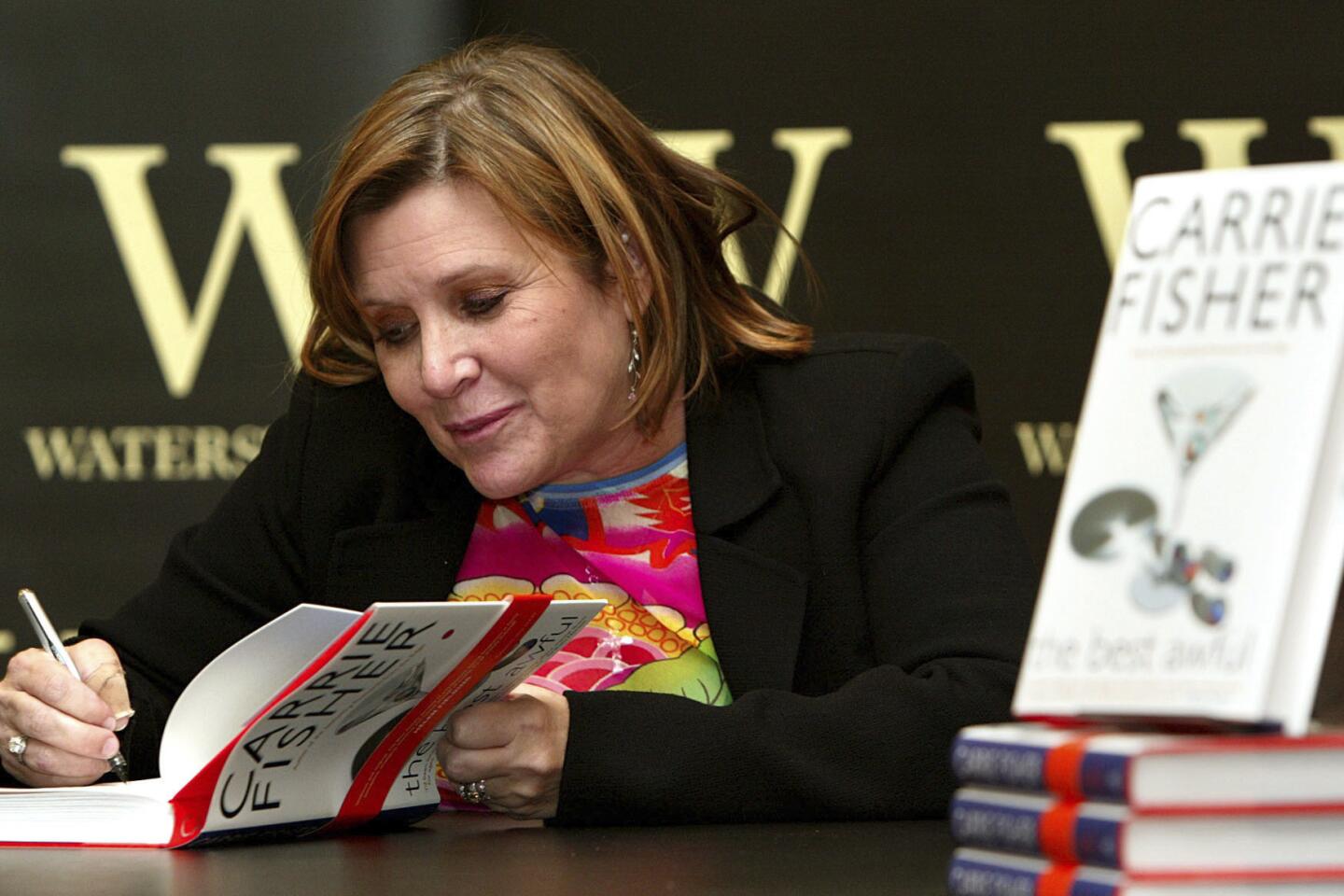

But then Fisher read the Dorothy Parker short story “Maybe Just a Little One,” about a woman’s losing battle to alcohol, and decided to write about a Hollywood actress looking for love and success and finding only drugs. Only six months out of the drug clinic herself, Fisher signed a contract with Simon & Schuster, began talking into a tape recorder and soon was writing her novel in longhand. MGM quickly optioned it, reportedly for a six-figure payment, and Mike Nichols is developing the film rights. Fisher is now doing the screenplay and steadfastly refuses to play the lead. “I already did that,” she explains.

Whether she will return to acting full time seems doubtful. For one thing, her movie career, which started so promisingly, has stalled. And even though she just finished filming an Agatha Christie mystery in Israel, she doesn’t seem too enthusiastic about it.

By contrast, she is bursting with plans for her second novel about a woman who writes for a soap opera. “I’ve even told my shrink about it. It begins, ‘I lost my virginity three times.’ I’m going to call it ‘Disappointment at the Salad Bar.’ ”

As couples with babies in tow pass by the food stands at the Farmers Market, Fisher looks a little wistful when considering the future. “Maybe I’ll marry again,” she notes. “Finally , I’m a human being, and I’d like to function as a human being on this planet. That’s what people do.” She stops and looks again at the faces of the families.

And, in typical fashion, she can’t help injecting her own brand of cynicism into the scene.

“Yeah, they get married and have children. And then they get divorced .”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.