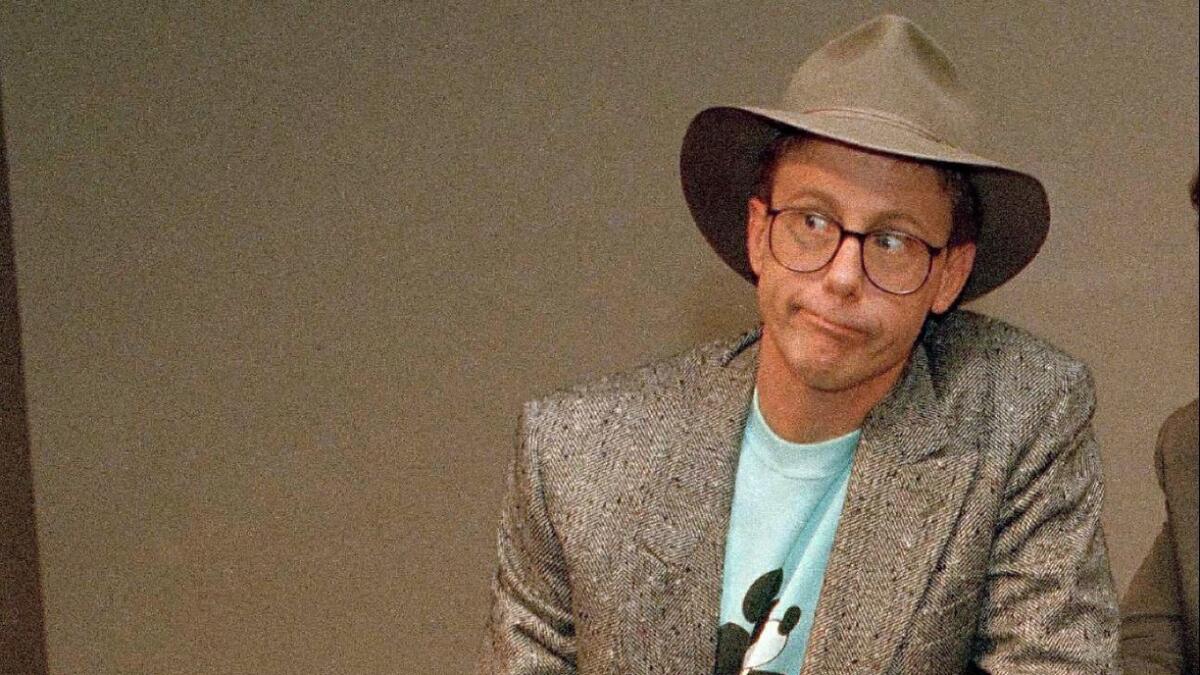

From the Archives: Harry Anderson: Bringing magic to the Big Easy

- Share via

Reporting from New Orleans — Actor and comic Harry Anderson, who portrayed the eccentric judge Harry T. Stone on the NBC comedy series “Night Court,” died on Monday at age 65. Below is a Los Angeles Times story, originally published on Nov. 28, 2005, in which Anderson discusses how he traded Hollywood for a new club of his own in the French Quarter and his role in the effort to revive New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. He and his wife left New Orleans in 2006 and moved to Asheville, N.C..

Harry Anderson, former star of the sitcoms “Night Court” and “Dave’s World,” rubbed the bags under his eyes, stubbed out an unfiltered Camel and climbed onto the small stage of his French Quarter nightclub.

“Hi,” he said. “I’m Ed Begley Jr.”

To get the joke, you have to know that Anderson is an entertainer, that Begley is an entertainer and that they look alike. Then you have to digest the irony of one reasonably famous person introducing himself as another reasonably famous person. Then you have to find that funny.

That’s a lot of hoops for a one-liner, and in a crowd of 80, one man chuckled quietly. But that’s OK. With decades of magic and comedy behind him, Anderson, 53, isn’t trying to win over a crowd, not these days. He’s trying to help save New Orleans.

He has opened his club, which was closed for weeks by Hurricane Katrina, to community meetings attended by a motley collection of advocates wearing tattoos, nose rings and plumed houndstooth hats.

Founded on frustration over the plodding pace of recovery and the perception that government promises to rebuild are disingenuous, it is a legislature of the strange and the dispossessed, and Anderson is the presiding officer.

The group meets once a week at Oswald’s Speakeasy. Yes, it’s named after Lee Harvey, with a drink called the Grassy Knoll and a periodic feature called the Zapruder Film Festival.

Some fanciful ideas have been proposed behind these doors in the last six weeks, including a plan to legalize prostitution as a way to renew tourism. But the merchants and residents are serious about many issues, peppering officials with questions about whether out-of-town police supplementing the locals will be savvy enough during Mardi Gras to distinguish between benign debauchery and actions that constitute genuine unlawfulness.

The group has been, at times, surprisingly influential. It was instrumental in persuading the city to ease the post-storm curfew in an effort to increase bar business.

In the meantime, Anderson has become a high priest of sorts among his fellow “Quarter Rats” — the faithful denizens of the district who see no need to travel outside its 78 square blocks.

Through it all, he’s trying to discern the future of a business empire that would only fly in New Orleans — his club, his variety show and his two shops, the one with a statue of a guy in a lobster suit and the other decorated with the framed skeletal remains of a cat named Fluffy.

Anderson’s charisma and an unusual skill set -- magic and comedy, along with picking pockets, piercing his arm with long needles and playing Beethoven on a recorder through his nostril -- helped give him a serendipitous career.

Playing variations of the same character — Harry the Hat, kindly con man — he worked the streets and the comedy clubs of Los Angeles. That led the way to a successful run on television, including “Cheers,” “Night Court” and “Dave’s World.”

Along the way, it became clear that things happen to Anderson that don’t happen to other people. (He once toured with a pet monkey, and a physician named Dick Chopp performed his vasectomy.) So it surprised no one when, in 1997, after 400 episodes of television, he quit.

Anderson had never been enamored with the L.A. scene. In all his travels, there had been only one city he had ever loved: New Orleans, where he had lived for two years, doing his shtick and, at one point, spending the weekend in Orleans Parish Jail when he got caught running a con on the street.

He took a scouting trip to make sure he wasn’t romanticizing the city. What he found was the anti-L.A. Cramped quarters were a great equalizer; no one has room to build a pool.

“And you’d look pretty stupid driving around the French Quarter in a Porsche,” he said. Everyone he met — hippies, artists, junkies, bikers — was in exile from someplace.

“Living in the French Quarter is the closest you can come to expatriating without leaving the country,” he said.

He moved here in 1999 and began to pursue what he had come to realize was his dream all along, to run a one-man variety act at his own club. He bought a building on a corner of the Quarter and opened in July. Five nights a week, surrounded by 88 seats, a totem pole and a sign for “Spade & Archer,” the name of the detective agency in “The Maltese Falcon,” he performed a 90-minute show called “Wise Guy.”

He did a bit called the “Middle Aged Straight Jacket Trick,” which entailed freeing one hand, reaching into his pocket for a $20 bill and paying an audience member to get him out. There were math and memorization stunts and dramatic stories told from the perspective of a carnival owner. He opened to so many standing ovations, he said, “I felt like Wayne Newton.”

He and his wife, Elizabeth, opened side-by-side shops that they tended by day. His was a magic shop where he shaved cards and made double-headed quarters. Hers was called Sideshow, and featured tarot cards and two-headed ducks made by a local taxidermist.

“Life was good,” Anderson said.

Katrina came two months later.

“It broke my heart,” he said. “We wound up with more businesses than there are tourists. I’m not sure that’s an exaggeration.”

The facade of the comic, the wisecracker always good for an easy laugh, fell away as Anderson walked through the Quarter, past the wharves that line the Mississippi, past a store selling prints from James Dean’s “Boulevard of Broken Dreams.”

New Orleans will never be the same, he said. But what will it look like? Will the pockets where much of the culture was created — the poor and largely black neighborhoods that shouldered the brunt of the storm — be rebuilt? Will New Orleans remain “real,” or will it become a city that is no more organic than the Disneyland attraction Pirates of the Caribbean?

“It’s teetered on that for a long time,” he said. “But it was always saved by individuals and iconoclasts. Now many of those people are gone. If you’ve lost the character of the place, what’s the product? What’s the place?”

He passed a few National Guard trucks, now a part of the scenery as much as the Quarter’s wrought-iron balconies. Flies feasted on rotting trash.

“How is business supposed to come back here?” he asked. “You can’t even use the name ‘Convention Center’ anymore, not after what happened. It’s like how people don’t name their kid ‘Adolf’ anymore.”

Everywhere he goes in the Quarter, locals shout his name or greet him with a smile and a handshake; he’s been one of the district’s more visible residents since he arrived. Some say he’s using the meetings as a springboard for public office, which he scoffs at.

One night, he opened the heavy doors of the club, and more than 100 people filed in. Anderson, who plays dueling roles as instigator and moderator, typically opens with a review of the latest events. For instance, Mayor C. Ray Nagin had decided to hold a New Orleans town hall meeting in Baton Rouge: “Apparently, there are more people who live in New Orleans who are now living in Baton Rouge than are living in New Orleans,” he explained with a sigh.

As the meetings have grown in size and stature, politicians and government officials have started showing up. Jimmy Fahrenholtz, a member of the much-criticized Orleans Parish School Board, arrived to talk about the transition to charter schools. He approached the microphone to chants of “School Board sucks!”

“It does,” he conceded.

“Don’t make me sorry I opened the bar,” Anderson cautioned the crowd.

A brave soul from the equally criticized Federal Emergency Management Agency, individual assistance officer David Hart, also came.

Hart addressed questions that have frustrated residents. For example: Do people who receive cash assistance from the Red Cross have to pay taxes on the check? (No, he told them.)

He also faced questions about why people who were displaced in precisely the same manner — sometimes from the same block — have been granted different levels of government assistance. Hart assured the crowd that people who submitted the same information to the federal government would receive the same benefits. “No!” the crowd shouted. “Wrong!”

A gay man held up his hand, and Anderson walked the microphone over. The man and his partner had applied separately for emergency cash stipends from FEMA, designed to help storm victims pay for essential needs such as food, shelter and clothing. Their applications were denied as fraudulent because FEMA’s computers identified them as a couple; each couple can only apply for one stipend.

“Why is it that the government won’t let us get married, but FEMA considers us married when it comes to handing out money?” the man asked.

Hart said he’d work on it. Anderson chuckled into the microphone.

“Gay-bashing was the only insult that FEMA hadn’t been accused of. Now we’ve got them all,” he said.

The meetings have resulted in community service, including a ride-sharing program for Quarter residents who don’t have cars and need to get to FEMA assistance centers.

There have been brainstorming sessions about the police force. One woman, a bartender at a Quarter club, pointed out that newly hired officers needed to understand that musicians frequently smoked marijuana while on break. They have to learn, she said, to spot the difference between a musician who is lighting up in an alley — a situation that typically receives a pass — and a “civilian.”

At times, ideas generated at the meetings sound outlandish, but they might reflect the kind of imagination that New Orleans needs now. One man’s proposal to shut down Louisiana ports until Congress pays for a stronger levee system — thereby holding a chunk of the nation’s goods hostage — drew an enormous ovation.

“How long is it going to be before we get off our knees in this city and start moving forward? That is why we do this -- to get some answers,” said Jim Monaghan, a friend of Anderson’s, an organizer and the owner of Molly’s at the Market, a French Quarter institution that stayed open through Katrina.

Anderson is going to try to stick it out in New Orleans. He plans to start his show again in January, which will require some Katrina material. He’s brushing up on his ventriloquism, which he hasn’t done for a while, so he can talk to a new character — an old, angry “coot” from Plaquemines Parish, the devastated coastal stretch south of New Orleans.

But he finds himself going over real estate listings at night, from Montreal and San Francisco.

“I’ll give it a shot. But I don’t know that a year from now I’m going to be here. Nobody does,” he said. “There are going to be some changes, and whatever happens, this city is never going to be what it was. In the meantime, if you don’t get involved, it will all be swept out from under you. So I’m doing what I can.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.