Clint Eastwood targets the legacy of Dirty Harry

- Share via

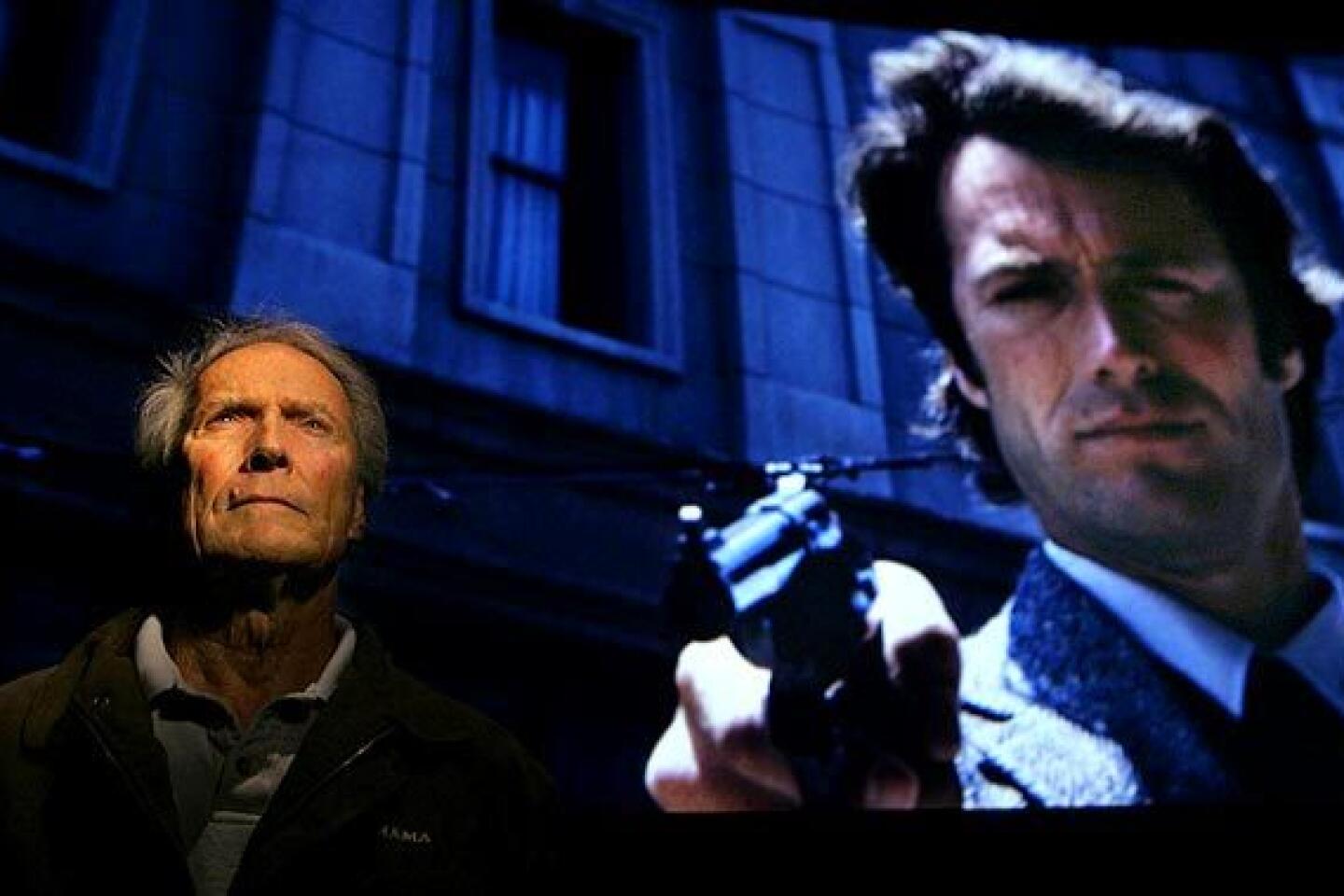

ON a recent afternoon at the Warner Bros. lot, Clint Eastwood took a break from a long day in the editing bay and strolled over to a hushed screening room. There, his armed-and-dangerous past was waiting for him, and the filmmaker winced when he looked it in the eye.

“Who’s that young fella?” he asked, a flicker of a smile crossing his famously craggy face. Up on the screen was Eastwood, circa 1971, staring down the barrel of a huge gun with an expression of cruel calmness. The role was, of course, Harry Callahan, the San Francisco cop with good aim and bad attitude, who opened fire in “Dirty Harry,” a movie that ushered in the modern American cinema of vengeance. He kept reloading for four sequels over 17 years, amassing a body count that began in the Nixon era and lasted into the twilight of the Reagan years.

Eastwood, who turned 78 on Saturday, has become an American filmmaker of the highest order -- he first rode to fame as a rangy, amoral redux of John Wayne but, somehow, came back from the desert as a latter-day John Ford. With that career trajectory, it wouldn’t be surprising if Eastwood turned his back on Callahan, whose darkly whispered one-liners (“. . . You’ve got to ask yourself one question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do ya, punk?” “Go ahead, make my day”) were long ago drained of any real danger by stand-up comics, politicians and bumper stickers. It’s easy to imagine Eastwood the auteur treating the character like a bad 1970s fashion choice.

Instead, Eastwood is reconnecting with the surly old gun nut. Warner Home Video on Tuesday will release a lavish new boxed set of all five “Dirty Harry” movies (the $75 DVD set includes 1973’s “Magnum Force,” 1976’s “The Enforcer,” 1983’s “Sudden Impact” and 1988’s “The Dead Pool”) that comes with a faux police badge tucked inside an eel-skin pouch. There’s also a letter to fans penned by Eastwood, who has been busy lately putting finishing touches on his latest directorial project, “Changeling,” and presenting it at the Cannes Film Festival (it hits U.S. theaters in November).

Sitting in the screening room at Warners, Eastwood explained that the role of Callahan was “a real turning point” for him -- and American popular culture. There’s also a sentimental aura around the first film: It was directed by the late Don Siegel, Eastwood’s mentor and friend, and brought the actor back to his hometown of San Francisco. He also knows that, for good or bad, in the minds of movie fans he will forever carry Callahan’s .44 Magnum.

“People are disappointed when they walk up to me and ask to see the gun and I tell them that, well, I don’t really carry guns,” he said with a chuckle. Eastwood was wearing sneakers and the relaxed posture of someone with complete confidence -- he might scowl on-screen, but in person he is more like the serene character he played in “The Bridges of Madison County.”

“All the movies you make, all these roles you take, and there are certain ones that people really hold on to. Harry is the one I hear about the most from the people on the street.”

The actor already was a screen tough guy thanks to the spaghetti westerns he made with Sergio Leone and his role as a maverick cop in Siegel’s “Coogan’s Bluff.” But something encoded in “Dirty Harry” set it apart and painted a target on it.

Andy Robinson, who played the Scorpio killer in “Dirty Harry,” said the movie cut through because of its grim hero and bundled appeal. “It was police thriller, a cowboy western and a horror film, it was all of them yoked together,” Robinson said. “And because of the times it was released in, it became the film that people argued about. Is it fascist? Is it ripe with irony? After that movie I was turned away at auditions for quite a while. A lot of people in Hollywood were angry.”

Although Pauline Kael of the New Yorker praised the film’s styling as “trim, brutal and exciting,” she also called it “a remarkably single-minded attack on liberal values, with each prejudicial detail in place -- a kind of hard-hat ‘The Fountainhead.’ ” Critic Roger Ebert wrote, “The movie’s moral position is fascist. No doubt about it.”

The reception was more enthusiastic on Main Street. The Warner Bros. franchise would gross $228 million in U.S. theatrical release -- big box office for the era -- and become a staple on TV and at video stores. “Clint should have been typecast forever,” Robinson said. “But he is bigger than Dirty Harry, which is saying a lot.”

Still, young men (and, now, older men) approach Eastwood and recite whole monologues from the movies or, even stranger, they grin and ask the graying actor to call them obscene names and threaten them. “In the early days, I would tell these young fellas, ‘That’s just a movie, pal.’ After a while, I just gave it to them. It made everybody happy. Sometimes it even made me happy. Sometimes I even meant it. . . .”

The pendulum’s swing

HOLLYWOOD was in a wild churn in the late 1960s. In “Easy Rider” and “Bonnie and Clyde,” the antiheroes were young, reckless and ready to break the laws of a hypocritical nation. The success of those films opened the door to a scruffy independent spirit that, politically, veered left. To many observers, “Dirty Harry” felt like a rebuttal. (It could have been worse -- “Dead Right” was an early title by screenwriters Harry Julian Fink, R.M. Fink and Dean Riesner.)

Siegel had been working in Hollywood since the 1930s (he put together the montage that opened “Casablanca”) and by the 1960s had found a flair for tough-guy cinema with Lee Marvin in “The Killers,” Steve McQueen in “Hell Is for Heroes” and Eastwood in “Coogan’s Bluff.” Siegel chose to open “Dirty Harry” with a reverential shot of a marble memorial listing all the San Francisco police officers who had been killed in the line of duty. No charming outlaws were being celebrated in this film.

“At the time in the press, there was a lot of attention to the rights of the accused, and that’s not bad or wrong, but nobody thought too much about the rights of the public or the rights of the victim, that’s not what the attention was on,” Eastwood said. “All of a sudden here was a picture about the rights of all the victims, and I think it really resonated with people who were frustrated.”

Eastwood has been a registered Republican since the 1950s but describes himself as a libertarian. He was appointed to an arts council by President Richard Nixon in the 1970s, elected mayor of Carmel in the 1980s and was appointed to the California parks commission (and then fired from it) by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. None of this, he says, has anything to do with Callahan.

“There was a lot made about the politics of the film, and what my politics were -- imagined and real. A lot of people thought I was a renegade. Everyone drew these things into it. Maybe they were there. Maybe they were reading stuff into it that wasn’t there. It’s a role. That’s the fun of being an actor, being something you weren’t.”

People ask him to autograph rifles, but Eastwood is no Charlton Heston. A vegan, he was distressed to hear Hillary Rodham Clinton boast recently about bagging a bird. “I was thinking: ‘The poor duck, what the hell did she do that for?’ I don’t go for hunting. I just don’t like killing creatures. Unless they’re trying to kill me. Then that would be fine.”

Eastwood said that he has a deep respect for due process and Miranda rights. But he added that there’s a benefit to feeding the fantasies of frustrated cops. “It’s gotten me out of a lot of speeding tickets through the years.”

A precedent set

INSPECTOR Harry Callahan’s nickname isn’t a reference to corruption -- it’s a nod to Callahan’s willingness to get his hands dirty, be it an illegal search or a bit of torture in times of duress. None of this is jolting now, not after “The Shield” and “NYPD Blue,” “Training Day” and “L.A. Confidential” and video games in which Callahan, with his tie and jacket, would be the most judicious cop on the screen.

But it was “Dirty Harry” that propelled the American urban vengeance film as a genre. The “Death Wish” franchise followed, and Eastwood was offered the lead as a gentle architect pushed to violence by hate and grief. He turned it down -- his screen persona was too defined as a scarred warrior -- and suggested the professorial Gregory Peck. The part went instead to the glowering Charles Bronson. “Sometimes,” Eastwood said, “this business isn’t about doing the thing that makes sense.”

The genre is still doing well. There’s a steady parade of straight-to-DVD productions that mimic the blood splatter of “Dirty Harry,” but there’s more ambitious fare as well. Most recently, there was Neil Jordan’s “The Brave One,” with Jodie Foster, of all people, confronting street punks with righteous sneers and gun-muzzle flare. Nicolas Cage is set to star next year in a Werner Herzog remake of “Bad Lieutenant,” a Dirty Harry cop taken to his most filthy extremes.

A lot of people imitate Eastwood’s Dirty Harry -- his personal favorite is Jim Carrey, who also happened to have one of his early movie roles in “The Dead Pool” -- but hearing the man himself recite the “Feel lucky?” speech is quite thrilling. He remembers every word, even though he said the last time he watched the film was a decade ago on laser disc.

Even better is listening to Eastwood run through a mock pitch of “Dirty Harry VI”: “Harry is retired. He’s standing in a stream, fly-fishing. He gets tired of using the pole -- and BA-BOOM! Or Harry is retired and he chases bad guys with his walker? Maybe he owns a tavern. These guys come in and they won’t pay their tab, so Harry reaches below the bar. Hey, guys, the next shot’s on me . . .”

Still, Rambo, Rocky and Indiana Jones have all returned. “Yeah, people ask me all the time. I guess if there was a truly great script or something, but it’s hard enough to find good scripts any time, let alone one you have to bend to make it fit some franchise. The movies that interest me now take me to new places.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.