The Player: With ‘Sky,’ thatgamecompany’s Jenova Chen wants to fix what’s broken with games

- Share via

The video game industry is broken, and not in the way a simple downloadable update can repair.

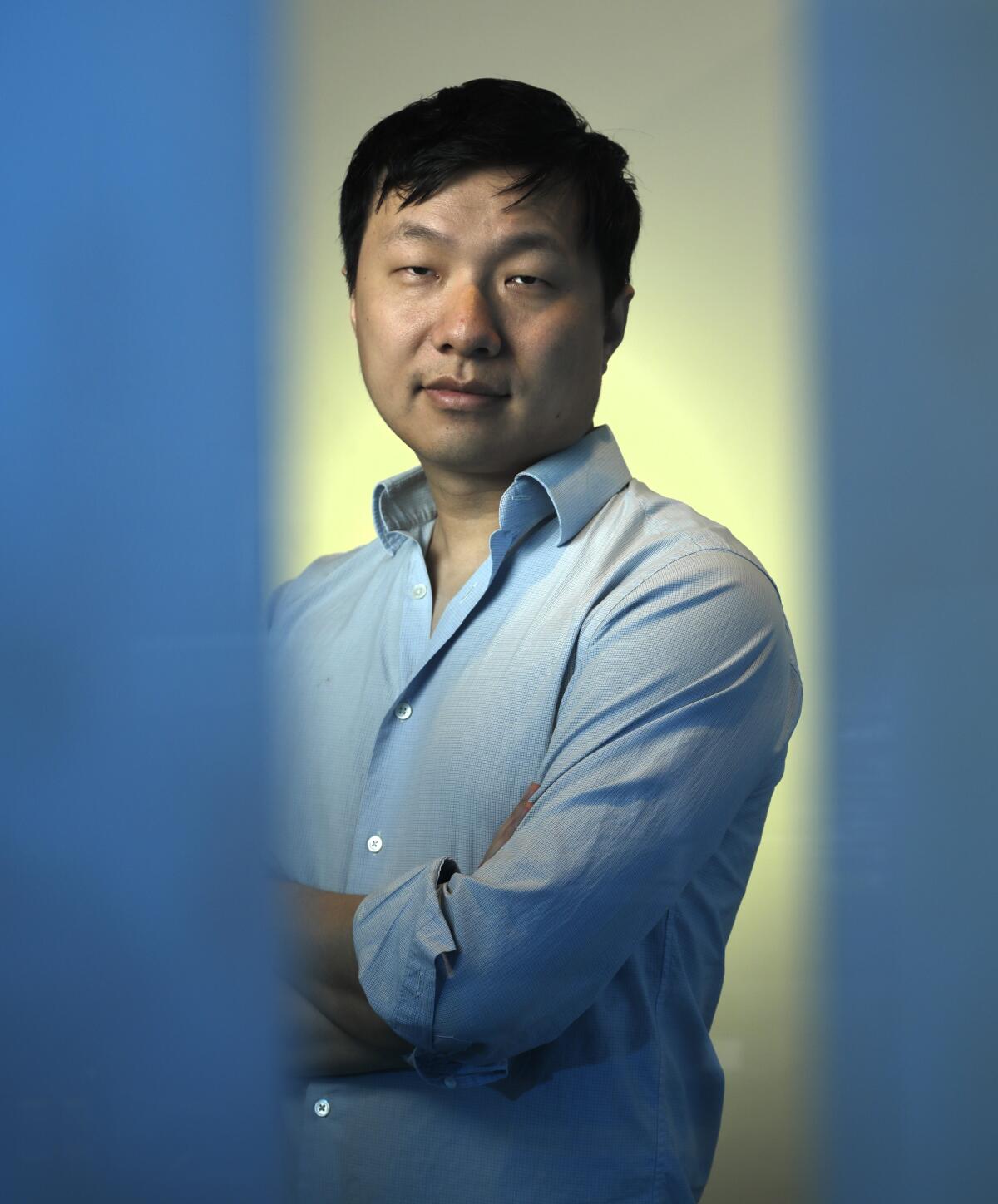

At least, that’s the impression one gets when spending time with Jenova Chen, the CEO of thatgamecompany and a developer who has spent much of the past decade attempting to persuade others — as well as himself — that the game industry can change.

The video game industry is “a flat note,” says Chen, 37, who dreamed up the 2012 release “Journey” after leaving Shanghai to attend USC’s game school. “Journey” was no mere student project; it sold more than 6 million copies, earned several “game of the year” nods, and helped ignite the now sprawling independent game scene.

One reason it had an impact: It reached beyond the usual gaming audience. “In terms of the emotional range of interactivity, games are very biased towards younger men,” Chen says. “So when I started the company, our mission was to create more emotions that a game can communicate.”

To make his case, Chen, at the start of the interview, opens a laptop and asks permission to give a presentation. This is clearly where Chen appears most comfortable. If one is going to make a game focused on love and caring, where advancement is helped by human collaboration at its most kind, you better believe Chen has the research — and the pitch — to prove his point.

His Santa Monica-based company has taken risks — and a path counter to the rest of the business — to focus largely on themes of compassion in its titles.

The latest example is “Sky: Children of the Light,” a game unlike any other, except maybe those also released by thatgamecompany. Debuting this week, “Sky” is a modern, interactive fairy tale. Its kingdom is alternately familiar — “Sky” pulls its imagery from the constellations, its mysteries from the stars and its language from music — and otherworldly, a place where candles are currency and its challenges are rooted in the quest to understand.

Plenty of games, Chen admits, have clever or moving stories, but when it comes to actual gameplay, it’s all just “shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting.” He says this while pointing to a presentational slide with recent movie box office successes broken out by genre, the aim to show that comedies, dramas, animated films and romances, though financially outnumbered by thrillers and superhero films, essentially dominate all other genres in terms of sheer output.

His goal is to reach those craving the interactive dramas, comedies and romances, and to, in essence, “attract more people who love games. We believe this is healthy for the industry.”

Though “Sky” is a multiplayer, online-only game, players don’t compete against one another. While it’s possible to play alone, “Sky,” being released first for Apple iOS devices, encourages collaboration. We fly together, we play music together and we explode fireworks rather than bombs. As we learn more about its mythical universe — i.e., become better at the game — we gain the ability to hug one another.

He’s releasing “Sky” first on mobile devices, in part because Chen envisions it as a family game, one spouses and children can play together on their own individual devices, and mobile is simply where the largest game audience resides. But also because the bulk of the free mobile game market annoys the hell out of him, and Chen wants to change that too.

“For every 200 million people who own a console, historically, there are now 2 billion people who fiddle around with games on their phone,” Chen says. “Suddenly, 9 out of 10 people have never experienced a high-quality game.”

Chen dismisses much of the field as “predatory”; the mobile market, he says, is dominated by games that attempt to get players hooked on endlessly making small purchases. Some have likened such mechanics to gambling or pay-to-win. Chen, then, looked into the future, and didn’t like what he saw — a medium whose most successful games would be dominated by violence, action and tacky, click-bait gameplay.

“I felt really, really sad. All the work we’ve been doing trying to make games appeal to more people, and make games look like a respectable industry, suddenly went backwards,” Chen says. “Now new people, their impression of games is this completely different picture. We want to use our game to change more people’s opinion of what games can be.”

It all may sound a bit hokey — altruistic, even. In fact, multiple people at thatgamecompany refer to “Sky” as an “altruistic game,” but that’s only because “Sky” relies on gifting items to other players rather than murdering them. That doesn’t mean the free-to-download “Sky” doesn’t have add-ons — players can purchase additional candles and down-the-road seasonal adventures. But to play it, “Sky” is sophisticated, slyly complex and not at all corny.

“Sky” appeals to our adventurous, inquisitive spirit. Its game world is laid out like Disneyland: a hub in the center that leads to various thematic realms. Among them: a welcoming and warming beach-like world, a spooky storybook forest and a fallen kingdom rooted in academics, where monuments and secrets are in ruins. A castle, broken, seems far away. There’s evil -- crabs, and even a dragon -- their goal to keep the game world that we seek to illuminate forever in the shadows.

The comparison to Disneyland is no accident. To brainstorm “Sky,” Chen spent quite a bit of time at the Anaheim theme park trying to understand its timeless appeal and how it encourages exploration of American pop myths. He also studied the company’s history and thinks the game industry has yet to have its “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” that is, a refined narrative work that appeals to high and low culture and forever changes the course of the medium.

Chen is aware he speaks in broad strokes, and he brings up “Myst,” an early 1990s abstract adventure that treated games with the seriousness of literature, before a journalist can. It’s a game that “Sky” will undoubtedly be compared to, and it’s long been considered one of the best-selling games of all time for its ability to reach beyond a core gaming audiences.

Yet games such as “Myst,” Chen says, are “very, very rare.” They’re the exceptions, and Chen is well-versed in exceptions. “Journey” was one, as players would drift among sandy landscapes and speak to one another only in song.

He’s not interested in making another exception, however. He wants to become the rule.

This is in part why thatgamecompany stayed independent, raising funds from venture capital firms, including $5.5 million from Benchmark Capital in 2012, rather than appealing, for now, to other game publishers. He didn’t want to answer to them so much as show them a way forward.

He’s well-aware of the risk, and every decision, including “Sky’s” release date, is clearly weighing on him. He wonders, for instance, if releasing the game on Thursday is too soon in the wake of Niantic’s augumented reality hit “Wizard’s Unite,” the company’s Harry Potter-themed follow-up to “Pokémon Go.” Chen jokes that “Sky” is the “Gattaca” to Niantic’s “Titanic,” referencing the year in film in 1997 when the James Cameron disaster romance dominated all cinematic conversation.

“I want to find a way to make this type of game a genre, so it does need to be a financial success,” Chen says. “It has to make a certain level of capital so that the investors and the publishers, like Activision and EA, say, ‘It looks like there’s opportunity there.’ After a Pixar or a Disney succeeded with ‘Snow White’ or a ‘Toy Story,’ immediately they were followed. It becomes an industry. What you need is the initial breakthrough, artistically and financially.

“Then,” Chen says, “you can change the industry.”

First, however, Chen had to inspire his own staff of 32.

Encouraging people to play nice was no easy task. “Sky” was revealed at an Apple presentation in 2017, but the game has been in testing since. It didn’t always go well. Early on, thatgamecompany tied “Sky’s” ability to gift and acquire candles to progression in the world, which turned friendship into something that was obtained rather than cultivated.

“One guy was like, ‘I’m leveraging my friendship to unlock content and collectibles in the world ... I want your candles just to unlock the cool stuff.’ It felt very inauthentic and greedy,” said writer Jennie Kong at a talk earlier this year at the Game Developer’s Conference in San Francisco. “We’re [thatgamecompany]. We don’t do greedy.”

The solution, easier said than done, was to begin to tie collaboration to the joy in play rather than simply amassing an inventory. That sometimes meant creating areas to interact outside the main story -- an ice rink perhaps, or to give players musical instruments. Slowly, collaboration became about the possibility of what could be done in “Sky” rather than what could simply be gained for character growth.

The sense of curiosity the game promotes will extend beyond it, says Vincent Diamante, the game’s audio director.

“I still consider myself a gamer. It’s actually really easy to get tired of all the excitement that everyone sort of puts out there,” he says. “It’s been a really fun ride making this game that’s not meant to be the typical stimulus that we see on the App Store and introduces people to something else that a game can be. I always felt excitement when I was younger in finding something that was different.”

Chen isn’t the industry’s only outlier of course. For one, he’s made a lasting impression on his former collaborators. “Jenova wants to connect deeply with other people, and desires to do so through his medium of choice -- video games,” says Kellee Santiago, a co-founder of thatgamecompany who left to pursue her own opportunities in virtual and augmented reality. “All of his works aim to both expand the reach of this audience, as well as deepen the level of connection players can feel with him, themselves, and one another.”

He also continues to advise the interactive arm of Annapurna Pictures, helping with fundraising early on and acting as a scout. Earlier this year Annapurna released “Outer Wilds,” another title from veterans of USC’s game school and one that is already spoken of in many circles as one of the best of 2019. “Its about helping artists who want to do something risky but couldn’t,” he says of his collaborations with Annapurna.

It’s important to stress that while Chen is adamant that games such as “Sky,” as well as independent, thoughtful content in general, can be a force for positive change in the game industry, he’s not being cocky. To believe otherwise is simply unthinkable.

“I believe what we’re doing is the right thing,” Chen says. “Everyone we talk to is very supportive. We’re being helped by so many people. I hope this will be successful because so many people want to help. But I also fear. I fear that all the goodwill will be in vain because I messed up this part or that part, or maybe it’s still too early for the market.

“I have so much fear. It’s hard to describe how I feel. It’s too overwhelming.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.