Saying goodbye to ‘American Idol,’ the talent show that took pop culture by storm

- Share via

After 15 seasons, “American Idol” declined to say goodbye. “One more time -- this is so tough -- we say to you from Hollywood, good night, America,” the show’s forever host Ryan Seacrest said in the final moments of April’s series finale. Then, as the show faded to black, he uttered two more words: “for now.”

“I think we probably felt [the end] was slightly premature,” “Idol” creator Simon Fuller says now of the decision to have Seacrest signal the show’s possible return, if not in its current form, then somewhere, somehow, sometime. “Idol” went out with its best finale ratings in years. “So,” Fuller says, “it was kind of like, hang on, before we start banging the nails in the coffin … ”

The moment -- the tease, the suspense, the element of surprise -- was quintessential “Idol.” From its first season on Fox, when a charismatic, talented, unknown singer named Kelly Clarkson bested runner-up Justin Guarini to become the show’s inaugural winner and propel herself to musical superstardom, the show always knew how to milk a moment and get people talking.

Premiering in 2002 in a country shaken by 9/11, a time in which Internet culture was relatively young, reality TV fairly new, and smartphones and social media had yet to alter the way we interacted, “Idol” brought people together for something positive, hopeful and empowering. It changed the music industry, the TV landscape and even the culture at large.

The lives, the careers, the futures of these kids were genuinely in their hands.

— Trish Kinane

The show minted real stars, launching the careers of winners including Clarkson, Carrie Underwood and Phillip Phillips and non-winners like Jennifer Hudson and Chris Daughtry. Its contestants went on to release No. 1 hits (459 of them to date), win countless awards (including 13 Grammys and 14 Academy of Country Music Awards), fill stadiums and dominate the radio. They starred in shows on Broadway and on TV. Hudson won an Oscar. Clay Aiken ran for Congress. Clarkson sang at the second inauguration of President Obama, who paid tribute to the show’s impact via video in the finale. “No other show has produced as many stars,” Seacrest says. “It’s impressive.”

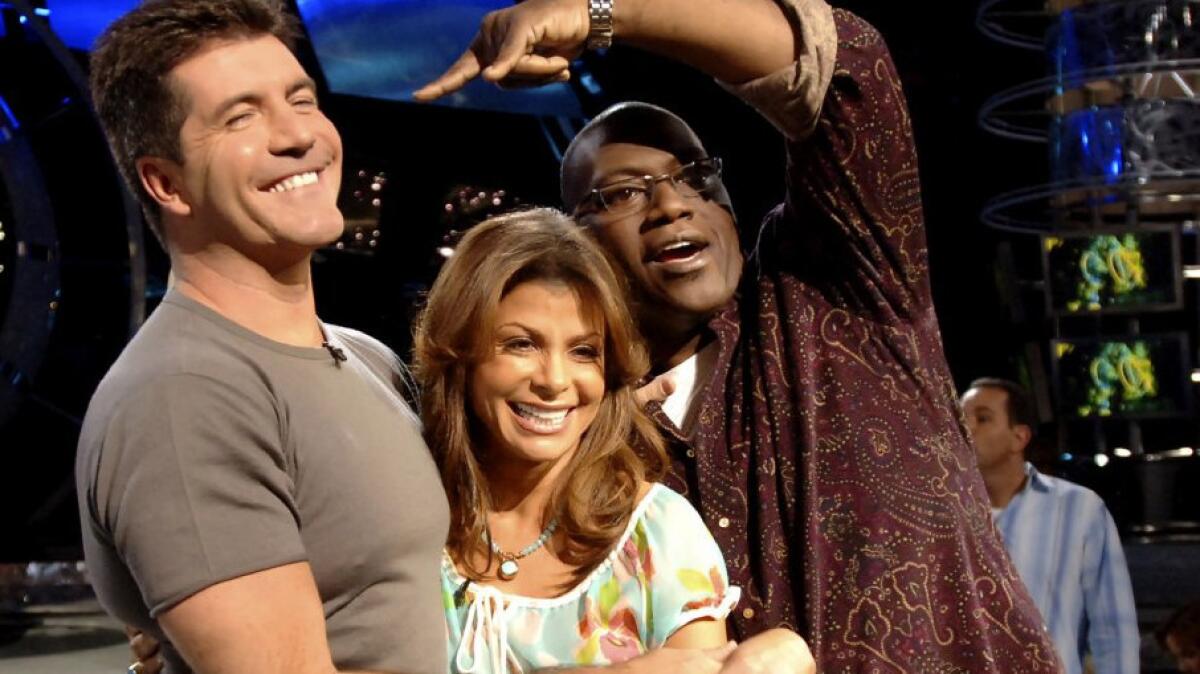

The Cinderella success stories may have been the heart of “Idol’s” appeal, but they weren’t the whole of it. Some viewers tuned in to watch the judges interact, especially the first panel (Simon Cowell, Paula Abdul and Randy Jackson) and the last one (Harry Connick Jr., Jennifer Lopez and Keith Urban), who seemed to have real chemistry. Others enjoyed the glimpse behind the scenes of the music industry.

But whatever they came looking for, especially in the show’s early seasons, American TV watchers tuned in in droves. At its height, the show boasted upward of 30 million viewers.

“It’s hard to say why lightning struck, but I think the formula worked from a format perspective, from a judging and talent perspective,” Seacrest says, noting too that “Idol” “was a show that families could watch together.”

The show’s watershed moment came at the end of Season 2, when more than 38 million viewers tuned in to watch Ruben Studdard defeat Aiken, by a wafer-thin margin after a huge night of voting, says Shirley Halperin, a music journalist who wrote the 2011 book “American Idol: Celebrating 10 Years.” “They just pulled every piece of drama that they could out of that finale,” she recalls. “And the next day all the newspapers, all the front pages of websites, everybody had Clay vs. Ruben as the top story. I’ve never seen a pop-culture water-cooler moment that big.”

In a way, it was a reality show, but it was also a kind of soap opera.

— Simon Fuller

“Idol,” for all its homespun charm, also signaled the future: the engaging, empowering effects of technology. “Technology had just got to the right place when ‘Idol’ started so people could vote, text and phone,” says the show’s executive producer Trish Kinane. “That made them feel they had some control. The lives, the careers, the futures of these kids were genuinely in their hands. I think that was very exciting.”

But the true secret to “Idol’s” success may have been its very simplicity. “Discovering new talent is always interesting,” Fuller says, adding that he worked to build on the talent-show format’s innate appeal and boost engagement and the emotional stakes by telling the contestants’ stories: who they were, where they came from, what struggles they had overcome. “In a way, it was a reality show, but it was also a kind of soap opera,” he says.

In “Idol’s” wake has come a flurry of reality TV talent shows – hits such as “The Voice” and “Dancing With the Stars” and misses such as “Rising Star,” “Duets” (Remember them? No?!) and the American version of “The X Factor.”

The show’s formula has been “copied endlessly” and “inspired lots of reality television,” Kinane says. “The stories that were told, the way technology was used, the interactivity, all of these things were shown to work, and I think it pushed those limits of audience participation, which now is almost commonplace. Everyone’s doing it.”

As for whether “American Idol” will return, Fuller, who is busy with a range of projects, including several involving virtual reality, says his answer changes by the day, but he’s “absolutely bursting with ideas” about how to reinvent a talent show in today’s landscape. Whether that’s a retooled “Idol” or a whole new show he’s not ready to say, “but certainly the advent of the real digital age, real interactivity and live-streaming, throws up a whole host of interesting opportunities,” he says.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.