Review: In ‘Poor Yella Rednecks,’ humor and pathos in the struggles of Vietnamese immigrants

- Share via

In “Vietgone,” playwright Qui Nguyen tells the story of how his parents met after escaping the Vietnam War and landing in the same resettlement camp in Arkansas. It’s a tale of traumatic displacement written and performed with unstoppable comic verve that sneakily brings the reality of the refugee experience vividly to life.

Nguyen picks up the story of his parents in “Poor Yella Rednecks,” which is having its world premiere at South Coast Repertory, where “Vietgone” also had its start. Once again the talented May Adrales is directing and once again dollops of vintage and contemporary pop culture are crucial ingredients in a playwriting brew that has the characters rap their feelings when words seem inadequate to the task.

“Vietgone,” which was produced last fall by East West Players, resembles at times a brilliant graphic novel animated for the stage. “Poor Yella Rednecks,” conceived as the second installment in an autobiographical series, has more substantial sitcom DNA. But it’s sitcom served with a wacky difference.

The new play retains the unique Comic-Con theater aesthetic that Nguyen developed at his Obie-Award winning Vampire Cowboys Theatre Company. Comic-book fight scenes, cartoon projections and puppetry figure prominently and, as with “Vietgone,” these nontraditional elements find ways of intensifying the work’s emotional wallop.

The Playwright (Paco Tolson) returns as a character in a play that glimpses its own creation. In the opening scene (jauntily set up by a “random British narrator”), Nguyen’s surrogate tries to get his 70-year-old mother, Tong (Maureen Sebastian), to recount the early days of her marriage. She thinks he should come up with a better idea for a play.

“No one wants to hear story about old woman who speak bad English with fat son,” she unceremoniously tells him. White people, she insists, have no interest in a Vietnamese refugee story.

“All sorts of people like watching plays, mom,” he objects.

“Yes, all sorts of white people,” she replies. “Look around — it look like a Fleetwood Mac concert … soo white.” (The audience at South Coast Rep couldn’t help exploding with laughter.)

Before conceding to share her story, she has a few ground rules. The play must be “true and hard,” so cut the phony love-at-first-sight sentimentality. She wants the white characters to sound as dopey as she hears them. And she would like to speak all fly like her son, who warns her he has a “potty mouth.”

“I want a pot and a mouth,” she affirms before transforming into an F-bombing younger version of herself. Tong, who has a lovesick American boyfriend, and Quang (Tim Chiou), who left behind a wife and children in Vietnam, are head over heels in lust. Quang proposes by rapping his feelings to a soulful 1970s groove. The couple vow “to make this place our new homeland,” knowing full well how difficult, if not impossible, this task will be.

REVIEW: ‘The White Album,’ Joan Didion and the seismic shifts of California in the ’60s »

Flash forward to 1981. A trailer in El Dorado, Ark. Huong (Samantha Quan), Tong’s fierce mother, is on the couch as an American sitcom blares inanely. She’s watching her grandson, Little Man, the Playwright as a child (played by a moon-faced puppet that’s voiced by Eugene Young and manipulated by Young and Tolson), who’s asleep in the other room.

With Tong working a late waitressing shift at a diner that’s about to go out of business and Quang hanging out with his buddy (also played by Young), grandma keeps an ear pricked for danger. When anyone approaches the front door, she brandishes a knife and looks crazy enough to use it. First-hand experience of war has taught her to be hyper-vigilant, but she gets a kick out of carrying this strange behavior to extremes in a country in which she will always feel like a stranger.

A crisis ensues when Quang receives a letter from his first wife, who survived the war and has somehow found out where he lives. Quang and Tong’s marriage is in short order annulled, causing family confusion that only escalates when Quang decides to send the couple’s joint savings to his wife and kids in Vietnam to appease his overwhelming guilt.

Quang is still devoted to Tong, but she decides she needs a break from him. Their separation is handled by Nguyen in the manner of a predictable rom-com that has been converted into one of those rackety sitcoms that grandma assumes is for American blockheads.

What elevates the writing isn’t the situational antics, but the stylistic variety in which the comedy is handled. Nguyen’s sensibility is invigoratingly hyperactive. When the humor starts to seem a bit too broad, the play shifts gears and turns to rap or puppetry or — heck, why not? — martial arts.

Adrales’ production accommodates this swirl with delightful ease. Jared Mezzocchi’s projections endow Arnulfo Maldonado’s set with childlike imagination. Shane Rettig’s original music allows the play to comfortably frolic in that borderland between comedy and musical.

Sean Cawelti’s puppet design gives Little Man an expressive vulnerability. As Tong scrambles to keep her household afloat, her son struggles to find acceptance at school. Caught between cultures and languages, he takes refuge in Spider-Man fantasies while wondering why his increasingly absent father is emotionally bribing him with an Atari set.

SPRING THEATER: Dianne Wiest, Lucas Hnath, Nia Vardalos and more »

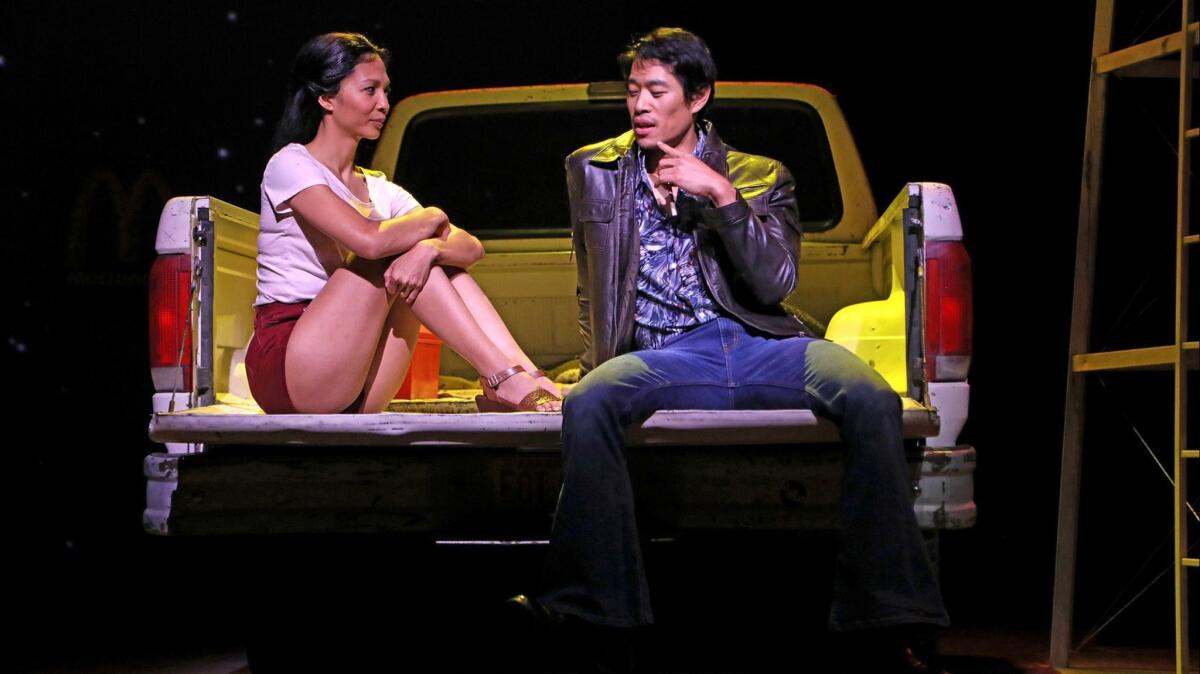

Sebastian’s Tong and Chiou’s Quang are as vibrant and sexy as any couple put through the romantic comedy paces on the big screen. Nguyen, heeding the advice of his mother in the play’s first scene to write true and hard, doesn’t sanitize his parents’ story. Quang has a one-night-stand; Tong tries to rekindle her old relationship with clumsy American Bobby, a “Vietgone” holdover played by Tolson in the gag-like broken English prescribed by Nguyen.

Resentment stands in the way of reconciliation for Tong, whose job situation grows dire. Money is scarce and grocery shopping with an empty wallet requires some fast fighting moves. Complicating matters further is grandma (played with more vigor than control by Quan), who resists the assimilation program her daughter has decided is necessary for the sake of Little Man’s future.

Some miracle of alchemy occurs late in the second half to bring all the various narrative and stylistic threads together in an emotional culmination that is too real to be described as a happy ending but is just as rewarding. What is the secret of Nguyen’s playwriting magic trick? Authenticity, for sure. Also, a personal story that is at the same time an under-represented American one.

“This is not a love story. It’s the story about surviving one.” The Playwright underscores his mother’s remark early on in the play. But “Poor Yella Rednecks” turns out to be a genuine love story of a family forced to reinvent itself repeatedly in a game of survival that might not be romantic but is remembered with courageous, comical love.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Poor Yella Rednecks’

Where: South Coast Repertory, 655 Town Center Drive, Costa Mesa

When: 7:30 p.m. Tuesdays-Thursdays, 8 p.m. Fridays, 2:30 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, and 2:30 and 7:30 p.m. Sundays. Ends April 27

Tickets: Start at $23

Info: (714) 708-5555 or scr.org

Running time: 2 hours, 15 minutes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.