Who is Hamlet? Three actors make their case

- Share via

Who is Hamlet? This might seem like a strange question to ask about the most famous character in all literature, a figure incarnated by some of the most brilliant actors of the last four centuries and the subject of a library of writing analyzing the political, philosophical and psychoanalytic meanings of his every move.

But “Hamlet” is a play of paradoxes, and perhaps the greatest of these is that the protagonist who reveals more of his mind than any other in Shakespeare remains something of an impenetrable mystery. His enigma may be the secret of his inexhaustible fascination.

Each encounter with the play promises new insight into an elusive character forced by festering circumstances to play a series of roles, none of which can be said to be the true Hamlet. The grieving Prince, who knows so much about acting that he gives technical advice to the strolling players, has been cast by the ghost of his dead father to star in a revenge drama, in which he brings to justice his murderous, incestuous uncle, Claudius.

“Hamlet” dramatizes the colossal mismatch between an infinitely complicated character and a primitive plot. T.S. Eliot thought the play was consequentially an artistic failure, but it is exactly this dissonance between Hamlet and the hackneyed avenger storyline that gave rise to an unprecedented classic.

An artist and philosopher rather than a vigilante by temperament, Hamlet shares with us his thinking, testing contingencies and provisionally assigning blame, most savagely against himself. But his behavior (the mad disposition he adopts, the taunting cruelty he shows Ophelia, the chilly disregard with which he shrugs off his murder victims) has been subject to an unusually wide latitude of interpretation. John Dover Wilson tried to settle matters in his 1935 book, “What Happens in Hamlet,” but this influential work has been met with as much argument as agreement.

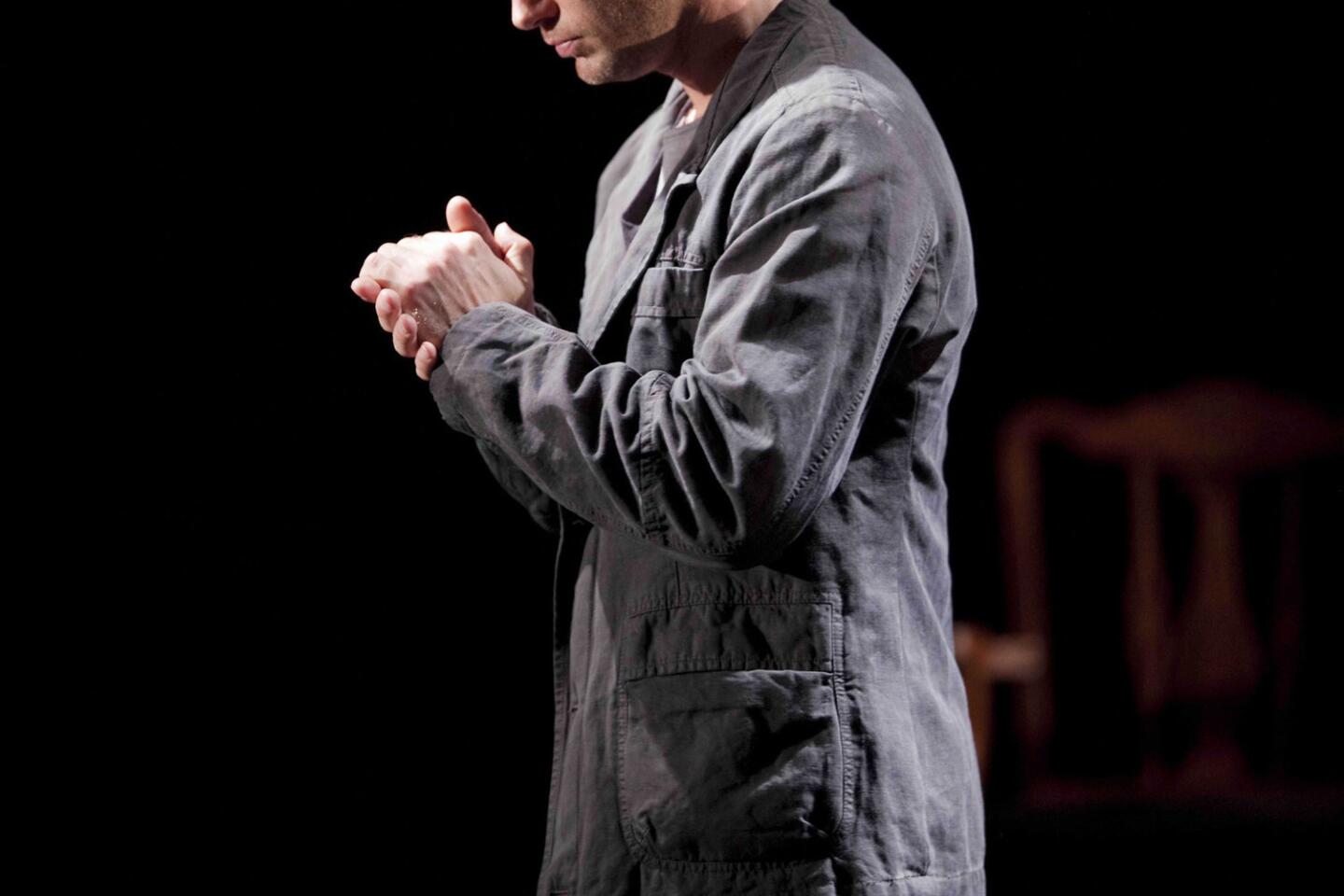

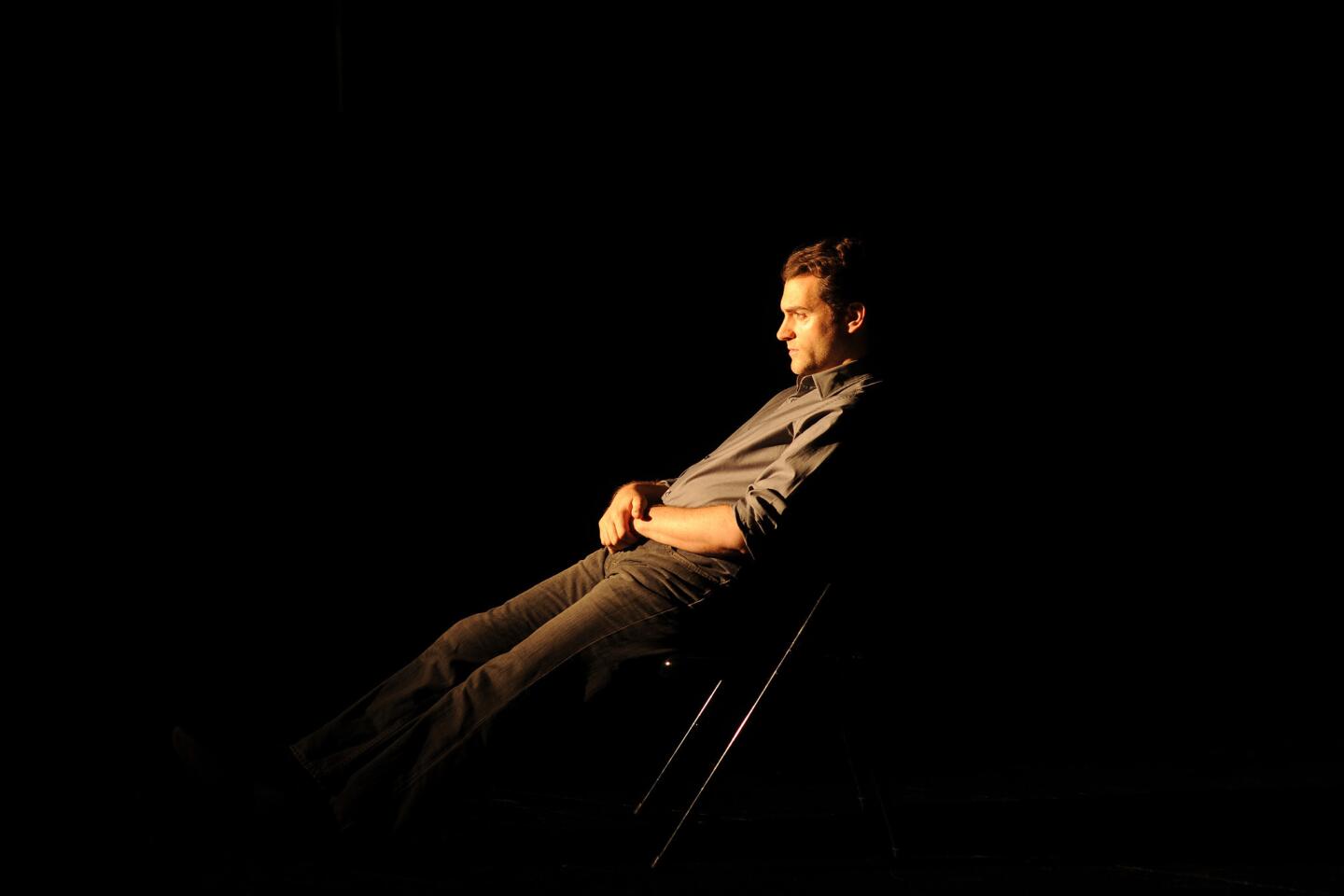

On a mission to better understand the melancholy Dane, I’ve traveled far and wide this summer to catch three modern day Hamlets: Irish actor Andrew Scott, slipping through the technologically enhanced surveillance state of Elsinore like a watchful cat in Robert Icke’s London production that transferred from the Almeida Theatre to the Harold Pinter Theater in the West End, is the most lucid of the trio. Oscar Isaac, sulking in a black hoodie at the start of Sam Gold’s production at New York’s Public Theater, is the most emotionally gripping. And Grantham Coleman, signaling his distress with graffiti on his body in Barry Edelstein’s outdoor production at San Diego’s Old Globe, is the most operatic.

Do any of these performances find the continuity in Hamlet’s divided character that Mark Rylance, the greatest of contemporary Shakespeareans, discovered in Ron Daniels’ 1989 Royal Shakespeare Company production when, trading his dark traveling clothes for stained pajamas, he followed the intuitive path of Shakespeare poetry? Not quite, but Scott (who plays the dastardly ingenious Moriarty on the series “Sherlock”) treats Hamlet’s every utterance as though it were newly improvised, and Isaac (“Inside Llewyn Davis,” “Star Wars: The Force Awakens”) uncovers the aching longing for a father whose death has only intensified a broken son’s need.

No matter the theatrical swirl buffeting them, [Oscar Isaac and Andrew Scott] never lose sight of the character’s inwardness.

Scott and Isaac rank as two of the best Hamlets I’ve seen. Both performers maintain a flamboyant intimacy. Their stage styles, at once theatrically provocative and somberly human, seamlessly integrate their screen acting experience. No matter the theatrical swirl buffeting them, they never lose sight of the character’s inwardness.

Scott’s clarity of intention breaks through every line reading. Even when Hamlet perplexes, his conduct seems to make psychological sense. More impressive, Scott miraculously fits Hamlet’s words to his contemporary tongue without sacrificing their lyricism. Shakespeare’s music is savored in a Dublin cadence.

The downside to Scott’s precision is that the pacing can feel sluggish. At times, the actor seems to be mentally translating Hamlet’s dialogue into personal feeling and then back again into Elizabethan language. The last hour of this four-hour production, while richly inhabited, tests the audience’s endurance.

Icke’s staging sometimes overdoes the contemporary embellishments. Bob Dylan’s music is spliced into scenes to intensify the philosophical brooding. But for the most part, an effective balance is struck between tradition and novelty. Ophelia (Jessica Brown Findlay) rolls out in a wheelchair in her crushing mad scene, and Beckett quite naturally haunts the graveyard comedy.

The bedroom confrontation between Hamlet and Gertrude (a searing Derbhle Crotty, who replaced Juliet Stevenson) is psychologically agonizing in a way that transcends the tired Oedipal reading. The politics of privacy is given an update with video screens tracking the movement of earthly and unearthly presences. But this “Hamlet” is at its most wrenching when Scott’s eyes widen at the horror of what has become of those closest to him.

Gold, who won a Tony for his staging of “Fun Home,” directed a much buzzed-about “Othello” last year that conjured the play out of a modern military barracks. I admired the startling scenic context, but the production (starring David Oyelowo as Othello and Daniel Craig as Iago) was ultimately undermined by a lax approach to the language.

Gold’s “Hamlet” cuts the lights for the opening scene. As the characters murmur in the dark about their encounter with a ghost who resembles the newly dead King, the lack of tunefulness and dismaying neutrality of the voices made me fear that Gold was once again offering a Shakespeare staging best appreciated on mute.

But Isaac comes to the rescue with impeccable diction married to raw emotion. The production rises to serve his performance. Gold’s staging, following in the auteur vein of Ivo van Hove, offers a profound theatrical meditation on the poetry of a play fixated, as Hamlet is, on images of debauchery, death, dirt and decay.

Narrowing the dramatic scope and making do with an ensemble of nine players, Gold concentrates on the play’s intimate relationships. Something is indeed rotten in the state of Denmark, but the state’s business is secondary to the disintegrating human drama exposing stark truths of our mortal condition. (An onstage cellist accompanies the death march, which proceeds, as Shakespeare prescribes, with a fair amount of twisted humor.)

Ophelia (Gayle Rankin), a goth girl with an eating disorder, stuffs her feelings with a pan of lasagna. The patriarchs of their respective homes, Polonius (Peter Friedman) and Claudius (Ritchie Coster) enthrone themselves on the toilet, oblivious of the tumult their tyrannous treachery has wreaked. Syringes creepily replace swords. The corpse of Hamlet’s father (Coster, nimbly swapping parts before our eyes) lies prostrate on a table strewn with ghastly funeral flowers, a tourniquet dangling from his arm.

Gold’s production is an advanced course requiring prerequisites. A first-timer to the play would likely be confounded by the doubling and tripling of roles. Making matters more unsettled, the tonalities of the performers are all over the map.

Charlayne Woodard grows in emotional power as Gertrude begins to understand her own culpability in her son’s nervous breakdown, but her regal grace is at odds with the jaded sneer of Rankin’s Ophelia. Keegan-Michael Key, who plays Horatio, helps us to see why Hamlet keeps this fellow student so close to his heart. But Key is weirdly asked in the dumb show prelude of “The Mousetrap” to do some physical comedy that might have been too ludicrous for his “Key and Peele” comedy show.

The directorial misfires, however, aren’t fatal. The production keeps returning to ultimate realities — vulnerable flesh and blood, cadavers that won’t stay buried, graves hungry to be filled up. The scene in which Ophelia covers her dead father and then herself with freshly made mud harrows the imagination. Hamlet begins his “To be or not to be” speech flat on his back, his depression luring him to the edge of an invisible abyss.

Isaac and Scott convey that sense of a noble mind overthrown by disgust at the adult world. Both portrayals vividly capture Hamlet’s mourning and mania. But the moral dilemma posed by the play — when is murder justifiable? — can’t be fully addressed unless the tragedy’s psychological, political and metaphysical levels are fused.

It takes an expansive production to communicate the larger meaning of Hamlet’s final act explanation to Horatio, “Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting/ That would not let me sleep.” Fortinbras, who seems to lack those introspective qualities that would have made Hamlet a wise king (if a lousy general), is cut by Gold and relegated to video by Icke. A minor character, Fortinbras (whose name means “strong in arms”) might seem expendable in such a defiantly long play, but his presence serves as a contrasting figure of power unburdened by conscience.

“Hamlet,” a play about an overwhelmed young man of brilliant intellect, is also about the choice, as Harold C. Goddard argues in “The Meaning of Shakespeare,” between imagination and violence, art and war. The tragedy, though dominated by its protagonist, transcends mere character study.

I had hoped that Edelstein, the Old Globe’s artistic director and one of the most knowledgeable Shakespeare directors in the country, would enlarge the scope in his outdoor staging of “Hamlet” in the Lowell Davies Festival Theatre. But the barnstorming style of the acting was so off-putting that all I could focus on was the disconnection between the words the performers were roaring and the reality of the characters’ situation.

After the deeply interior Hamlets of Scott and Isaac, performances in which Hamlet’s treasured monologues are winced as much as they are enunciated, I had trouble with Coleman’s approach to the text as a score to be thunderously vocalized. He wasn’t the only cast member melodramatically projecting lines in a manner that might have inspired Shakespeare to issue some further advice to the players.

“Hamlet” has an uncanny way of holding the mirror up to whatever age is examining it. The Romantics saw their freedom-loving reflection in Shakespeare’s masterpiece as clearly as the Freudians discerned their own Oedipal obsessions.

One thing, however, never seems to change: Audiences today, like those of yesterday, want to be taken inside Hamlet’s mind. Realistic acting has transformed as screens have become more pervasive. Whereas once we wanted a close-up of Hamlet, now we demand an MRI.

Shakespeare invites us to undergo Hamlet’s suffering, to grapple with the mystery of identity, to recoil at the deceptive nature of appearances and to relive the trauma of growing up. We may never be able to answer the question, “Who is Hamlet?” But by the end of the play, we come to understand that, as the sage critic William Hazlitt once observed, “It is we who are Hamlet.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

A few noteworthy Hamlets

Daniel Day-Lewis. A dashing, athletic and completely overwrought Hamlet in Richard Eyre’s 1989 National Theatre production that featured Judi Dench as Gertrude, Day-Lewis walked off the stage mid-performance and never worked in the theater again. The backstage legend was that Day-Lewis had encountered the ghost of his father, though years later, the actor who famously lives his parts offered a more conventional psychological explanation.

Liev Schreiber. With his rhetorical command and interpretive boldness, Schreiber announced himself as the best equipped American Hamlet since Kevin Kline. Unfortunately, Schreiber’s performance, boiling over with a grief that edged into sardonic fury, was undone by the madcap auteur antics of Andrei Serban’s 1999 Public Theater production.

Simon Russell Beale. No Hamlet in recent memory has handled the soliloquies with the depth of feeling and verbal finesse that Beale showed in John Caird’s National Theatre production that traveled to the U.S. in 2001. Beale gave us an ardently bookish Hamlet, a graduate student too in love with learning to finish his dissertation. But the poetry trumped the drama. Beale came off as an angry fusspot in his scenes with Ophelia, and when he vowed to drink hot blood, it was clear he’d rather turn on the kettle and pick up a good novel.

Adrian Lester. Perhaps this young century’s most elegant Hamlet, Lester deployed his velvety voice and physical grace to intermittent glory in Peter Brook’s distilled staging, which toured the U.S. in 2001. Brook may have been too ruthless in his editing, paring the politics along with a good deal of plot, but Lester’s sensitivity added density and light.

Jude Law. The most underrated of the modern Brits (Ralph Fiennes, David Tennant, Benedict Cumberbatch) who have prominently tackled the role, Law wasn’t simply a matinee idol out for a prestige stroll. A vigorous, always-in-motion Prince, he may have raced frantically through a few of the soliloquies, but he infused refreshing momentum into Michael Grandage’s 2009 Broadway production (which originated at London’s Donmar Warehouse). Hamlet’s therapy session was canceled. But the tale, thrumming with suspense, revealed why it’s timeless.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.