A bilingual painting and how the Huntington’s ‘Visual Voyages’ changes the story of art and science

- Share via

The 19th century engraving is striking for its blue skies, its placid clusters of llamas and the elegant profile of the Ecuadorean volcano Chimborazo looming over a broad Andean plane.

But the print produced by the Paris workshop of F. Schoell is more than just another placid landscape. It was drawn from a painting created by Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), the German naturalist whose journeys throughout Latin America led him to develop the revolutionary idea that species didn’t exist in isolation, they inhabited part of a larger whole.

“View of the cordilleras and monuments of the indigenous peoples of the Americas,” as the print is titled, captures such an environment. It is currently on view in “Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin,” at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, an exhibition that seeks to issue a corrective on the stories we tell about art and science in colonial Latin America.

For much of Western history, the conventional wisdom has been that scientific discovery was mainly taking place within the confines of nations such as England, Germany and Italy. But the Spanish colonization of the Americas resulted in an unprecedented level of research and sophisticated levels of knowledge cultivation and image-making.

“There is this idea that the only people who were making scientific discoveries about the natural world in that period were doing it in Europe and that it had nothing to do with Latin America or the Spanish world,” says exhibition curator Daniela Bleichmar. That is simply not true.

Even as colonization proved disastrous for the continent’s indigenous groups, many of the artists who worked on key scientific expeditions were indigenous — and some of the work reflects a distinct fusion of European and pre-Columbian tradition and thought.

“The production of art and the people who did that were much more diverse than has been credited,” Bleichmar says.

Part of the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA series of exhibitions around Southern California, “Visual Voyages” has dozens of rare objects — including one-of-a-kind codices, fragile prints and curious maps. Bleichmar tells the stories behind several of the show’s most intriguing works, including two about pineapples and a painting she describes as “bilingual.”

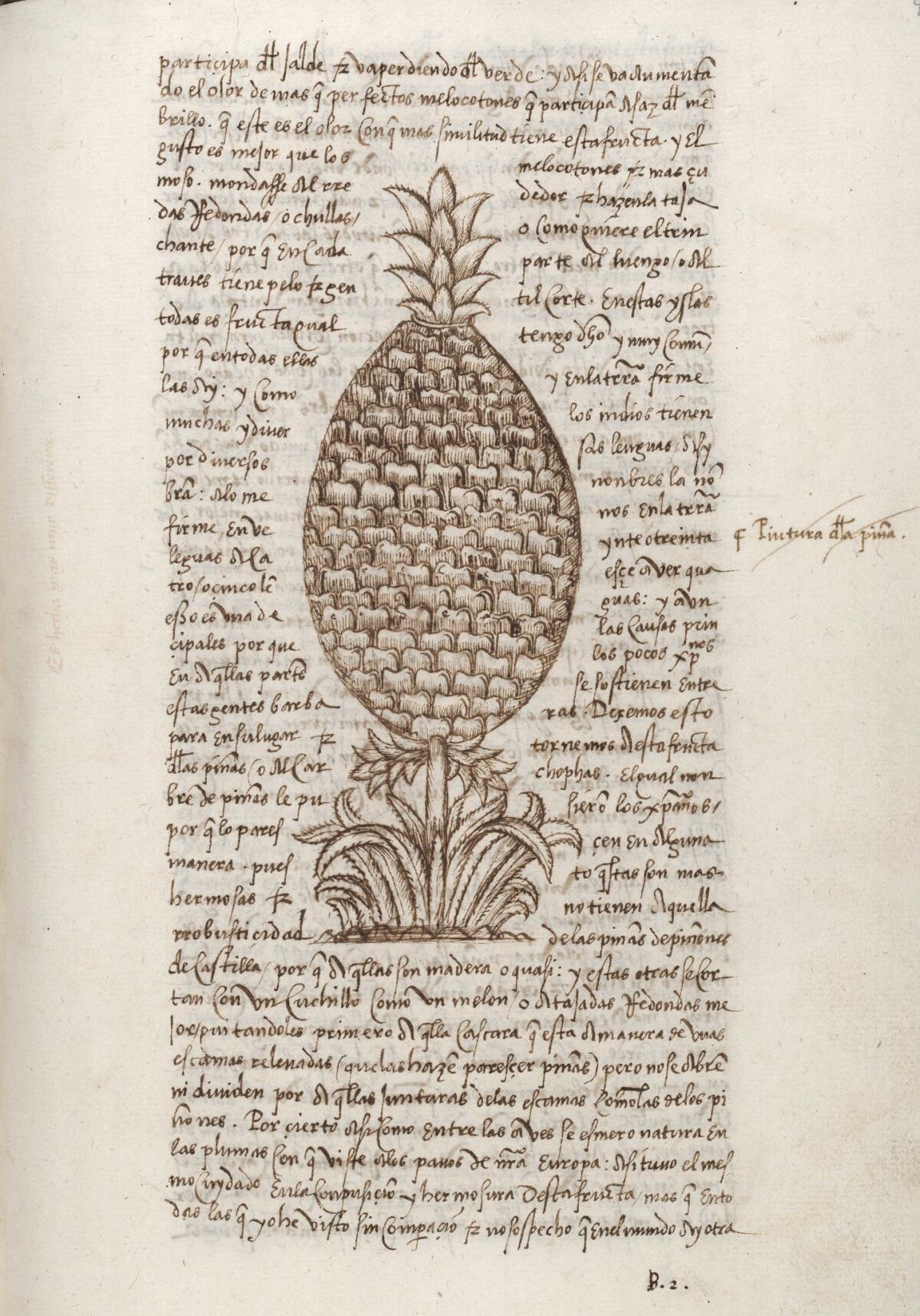

A first pineapple

The only one of the five senses that is not pleasantly rewarded by this magnificent fruit is the sense of touch.

— Spanish explorer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, 1526

The work in “Visual Voyages” captures the sense of wonder that many European explorers felt when they landed in the Americas and encountered plants and animals that were entirely unfamiliar. This includes a fundamental work by the Spanish explorer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo: “Summary of the Natural History of the Indies,” published in 1526.

“It’s the first European book written about the nature of the Americas,” says Bleichmar. “It has a huge impact in intellectual and scholarly circles.”

Of particular note is a page that shows an illustration of a pineapple that is straight out of science fiction — the first image of a pineapple drawn by a European.

“It’s about someone trying to depict something they have never seen before,” says the curator. “And the text is really awesome too. He’s saying, ‘Imagine describing a pineapple to someone who has never seen one? It is like taking apples and quinces. And how do you describe what it tastes like? Well, it’s better.’ And he’s like, ‘The only one of the five senses that is not pleasantly rewarded by this magnificent fruit is the sense of touch.’ It’s so earnest.”

‘Discovering’ America

Early depictions of the Americas by Europeans were filled with awe, but they were also rife with stereotype and violence. A key work in this regard is the early 17th century print by the Netherlandish printmaker Jan van der Straet that shows the Italian navigator Americo Vespucci — the explorer for whom the Americas is named — landing on the shores of the New World.

“It’s so interesting and so troubling,” says Bleichmar. “There’s a man, there’s a woman. He’s standing, she’s laying down. He’s clothed, she is not. He has instruments of science and religion; she is exotic and natural. He is protected, she is practically saying, ‘Take me.’ It’s so transparent in its message.

“There is a verse at the bottom saying that it’s ‘Vespucci arriving in the Americas’ and that ‘he calls her with his own name and she arises.’ The idea is he conjures her into being and takes possession with his name.”

The print features various elements of the natural landscape, including a sloth and an anteater. It also features a group of natives barbecuing a human leg in the distance.

“Cannibalism was the great boogeyman trope of the Americas,” says Bleichmar. “It’s what Europeans used to justify a lot of attitudes.”

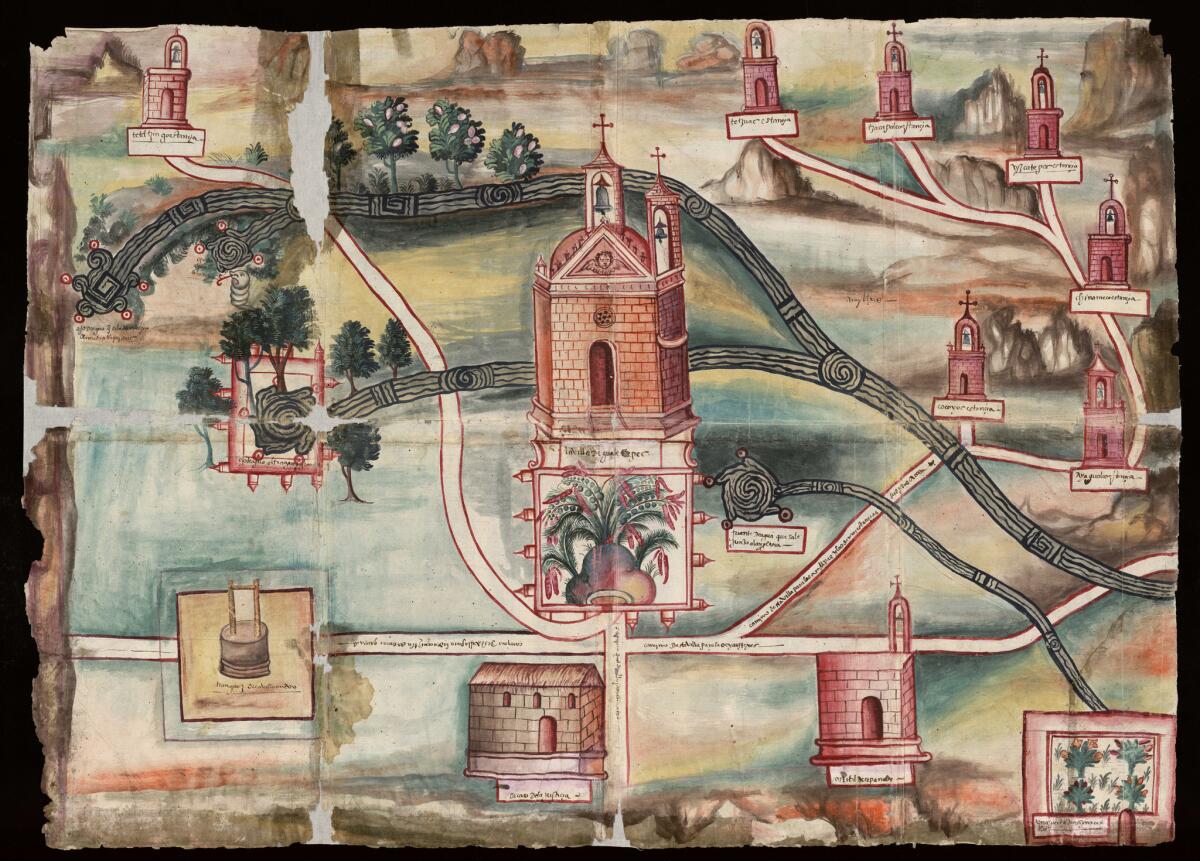

A bilingual painting

The colonization of the Americas required an unprecedented mapping operation of the physical landscape. To achieve this, the Spanish crown would send questionnaires to new settlements with a list of details that needed to be recorded. “There are dozens of these questionnaires and dozens of these maps,” Bleichmar says.

In “Visual Voyages” is a poignant map of the settlement of Guaxtepec (today Oaxtepec), located south of present-day Mexico City. It marks elements of the natural landscape and human settlement. And the work, painted by an unknown indigenous artist in 1580, offers a hybrid worldview.

“You have all of the estancias and they are all shown in the style of the Europeans,” Bleichmar says. “But the way of depicting water is coming straight from indigenous painting traditions. You see irrigation canals. You see this technology. And at the bottom you see a walled garden: Guaxtepec was famous because it was where Moctezuma had a garden, an orchard.

“If you look at the center, you see the name ‘Guaxtepec’ written in alphabetic Spanish. But you see also see this hill with plants coming out of it. That’s the indigenous way of writing ‘Guaxtepec.’”

“The artist is pictorially bilingual,” she adds. “They have both artistic languages. That is so powerful.”

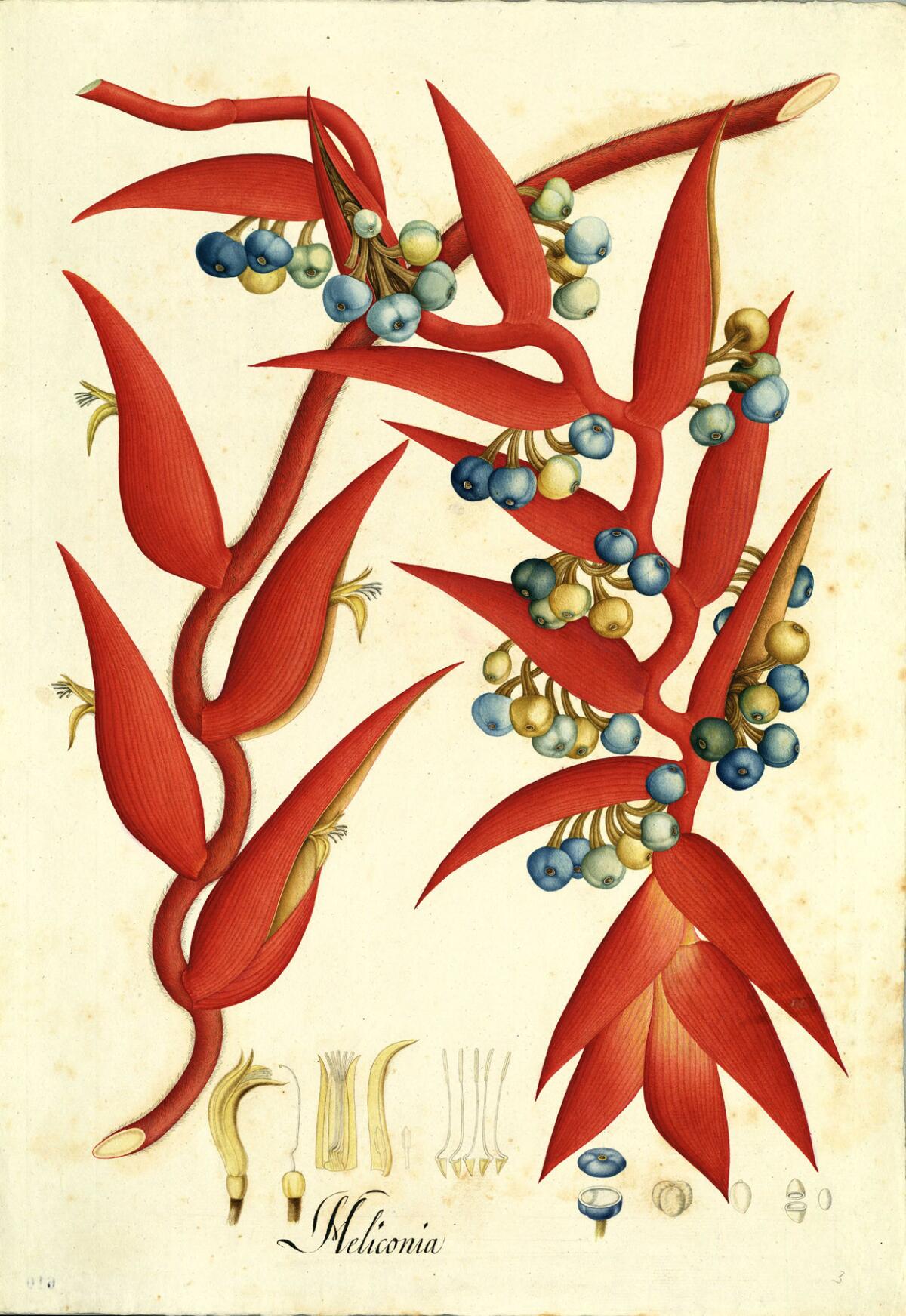

An American school

In 1783, the Spanish physician and naturalist José Celestino Mutis launched a three-decade expedition in the Viceroyalty of New Granada in South America (current-day Colombia and Venezuela). To record the region’s flora, Mutis had a team of 60 artists based in Bogotá who created almost 7,000 exquisite renderings of palms, trees, grasses and flowers (such as the heliconia depicted above).

“There are other expeditions,” says Bleichmar, “but nothing compares to this one.”

In those days, specimens (dead ones) were often shipped to Europe and painted there. Mutis realized that the best interpretations of nature came from the people who knew it best: the indigenous people who had studied it for centuries.

So he established a free drawing school in Bogotá to train artists just for this purpose. The resulting drawings are far more evocative than anything coming out of Europe.

“They are taking European ideas and finding the local idiom,” explains Bleichmar. “The colors are punched up and the details are incredible.”

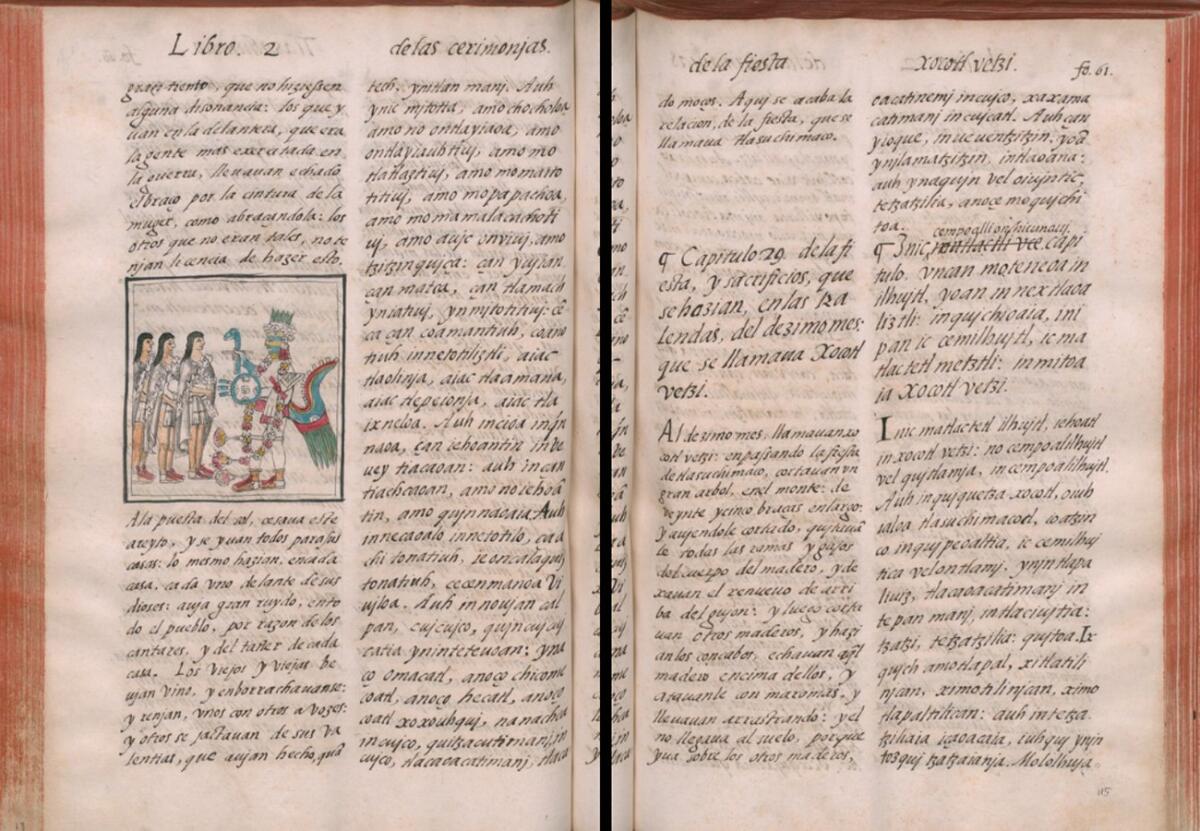

Two world views

They are the super-scholars of the time.

— Daniela Bleichmar, "Visual Voyages" curator

On view in the show is one of the most important works to emerge from Mexico during the period of colonization: Spanish friar Bernardino de Sahagún’s “Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España” — which translates to “General History of the Things of New Spain” and is otherwise known as the “Florentine codex.” (It resides in the Laurentian Library in Florence, Italy.)

Its three volumes, written in both Spanish and Nahuatl (the Aztec language) in the 16th century, offer a European and indigenous view of the world. Sahagún worked with indigenous scholars to create a record of the region’s daily life and natural history.

“They are men educated in this super-elite school created for the indigenous elite,” Bleichmar says. “They are highly educated in the European tradition. They speak Spanish and Latin. They also speak Nahuatl. They are the super-scholars of the time. And they go and ask questions of older indigenous people on every aspect of native history, culture, life, everything.”

The “Historia general” has sections on religious beliefs, societal structures and medicinal plants — containing specialized information about topics as specific as women’s health.

“Part of what’s fascinating is that it’s bilingual,” says the curator. “It’s written in Nahuatl and Spanish. But the texts aren’t literal translations. It’s the Spanish take on something and the Nahuatl take on something. So if you are trying to get a take on a culture with no written records, this is an incredible record.”

Mystical nature

Over time, Spanish American writers and thinkers and artists, they started fighting this idea of Latin American nature as the playground of the devil.

— Daniela Bleichmar, "Visual Voyages" curator

As the continuous retelling of colonization would have it, Europeans were the scholars bringing scientific knowledge to the Americas, while indigenous people had a more magical worldview — seeing the landscape as a place charged with the mystical power.

Not quite.

For one, indigenous peoples had developed vast areas of scientific and mathematical knowledge. Plus, Europeans were just as likely to see the natural world as an embodiment of spirituality. In fact, this was a trait, says Bleichmar, that both Europeans and indigenous people shared.

“Whether you are talking about Native Americans or Europeans, what would have been unthinkable was the idea of a separation of nature and the spiritual world — the idea of a secular nature,” she explains. “For everyone involved, nature was filled with spiritual beliefs.”

Perhaps there is no better evidence of that than an image found in the 17th century relations of the Jesuit priest Alonso de Ovalle, who chronicled Chile — which shows a tree purportedly growing in the form of Christ on the cross.

“Initially, European people would look at Latin American nature and see it as a bit threatening,” says Bleichmar. “But, over time, Spanish American writers and thinkers and artists, they started fighting this idea of Latin American nature as the playground of the devil. … And they start to create these images of nature that embodies the divine.”

Woman’s work

The only known female artist in the show is artist Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717), the daughter of a noted German printmaker, who was renowned for her vivid and visceral depictions of flora and insects. Merian’s plants never look like staid scientific samples — they pulse and teem with life. And in her drawings, she often includes animals and insects.

That’s partly because Merian preferred to do her drawings from living specimens. In 1699, recently divorced from her husband, she sailed (unaccompanied by a man) to Suriname to do just that.

“She tries to learn as much as she can about the local nature,” says Bleichmar. “She finds that the people who can tell her the most about the plants are the indigenous people and the black slaves. So they collect information for her. She produces these beautiful works of art. And she does all of these innovations with the printing.”

In 1705, after returning to Europe, she publishes “Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium” — “The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname,” which features frogs, toads, lizards and spiders depicted life-size and in full-bore color. Her works were as appealing to scientists as they were to collectors.

“She is,” notes Bleichmar, “one of a kind.”

“Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature From Columbus to Darwin”

Where: The Huntington, 1151 Oxford Rd., San Marino

When: Through Jan. 8.

Info: huntington.org

ALSO

How a migrant woman's death influenced Alejandro Iñárritu's Oscar-winning VR project 'Carne y Arena'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.