These racially insensitive remarks by Kanye West collaborator Vanessa Beecroft have the art world talking

- Share via

Some magazine stories are read in the same way horror movies are watched: Nervously, through your fingers, while imploring the main character not to open the closet door. Such is the case with Amy Larocca’s recent New York magazine profile of Vanessa Beecroft, the Italian British performance artist and Kanye West collaborator, in which the now L.A.-based artist offers a series of squirm-worthy observations on race.

Stuff like:

“I have divided my personality. There is Vanessa Beecroft as a European white female, and then there is Vanessa Beecroft as Kanye, an African-American male.”

Or:

“I had wanted to move to the States because of the presence of African-Americans. When I landed at JFK, my first impression is being welcomed by all of these African, or maybe Jamaican, air people that help you at the airport with your luggage. They were so kind. Welcome! I was so happy to see mixed races. In Italy, they are in the street selling gadgets.”

There is more. There’s the fact that she refers to her minimally furnished Hollywood Hills home as a favela — a slum. There is her abiding admiration for the inherent hotness of the people of South Sudan. (“Everyone looked like Alek Wek!”) Or how the clothes worn by Rwandan refugees inspired a fashion show she styled for West.

Of the refugee piece she said the following (which I’m not making up):

“The image came out of one of my books, and I thought, Perhaps this is Woodstock, because it looked really fashionable and glamorous, but no. That was a refugee camp...”

Not only does Beecroft open the horror movie closet door. She walks right in.

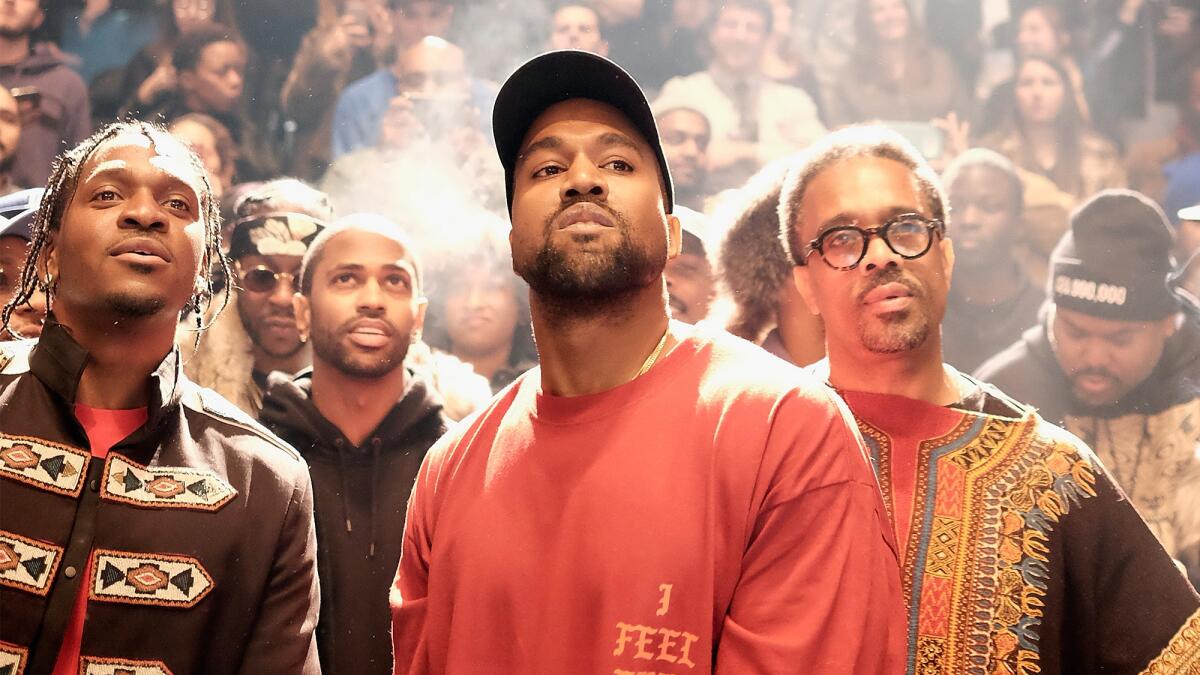

Beecroft became known in the U.S. in the mid-1990s for staging performances that featured monochromatic arrangements of nude or barely clothed models in body paint who often glared at viewers with empty or defiant stares. About a decade ago, she left the art world and began collaborating with West — orchestrating his fashion spectacles, which are held in locations like New York’s Madison Square Garden arena.

As she told ARTnews in February of collaborating with the rapper: “When he approached me I decided to work with him because he was my alter ego: An African American male, and I was a white woman.”

Perhaps what makes this statement, and so many others quoted in the Larocca profile, so uncomfortable is that Beecroft repeatedly expresses an interest in being black, but in a way that is totally divorced from the social issues connected with being black.

At a time when issues of race and police brutality are in the news almost daily, when cases related to political disenfranchisement are being battled in court, Beecroft’s observations display a staggering level of tone deafness. Not to mention that she lumps Africans, African Americans and Caribbeans into a single interchangeable category of black.

Since the story first emerged this week, there has been a tidal wave of hot takes on the matter, many of which compare Beecroft to Rachel Dolezal, the white Spokane, Wash., activist who passed as black, until she was outed by her family last year. (Though I’d argue that Dolezal had a better handle on the social issues facing African Americans — she was an activist, after all.)

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Art F City offers the best analysis of the bunch (Warning: link contains a nude image). Writers Michael Anthony Farley and Corinna Kirsch parse various historic Beecroft interviews, as well as a documentary that chronicled her trip to South Sudan and shows that the artist’s superficial fetishization of race is nothing new.

Just keep your hands cupped over eyes as you read.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Artist Mark Steven Greenfield on minstrelsy and American culture

Why two artists surveyed the U.S.-Mexico border ... the one from 1821

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.