Column: Studio Visit: Ingrid Hernandez, forging an artistic record of Tijuana’s impromptu settlements

- Share via

Reporting from Tijuana — Pay a visit to the workspace of artist Ingrid Hernandez and you will see a neighborhood emblematic of Tijuana.

The Barrio Burócrata Ruiz Cortinéz offers a spectacular mishmash of architectural styles: modern roof lines, Italianate balustrades and wooden walls made from recycled architectural elements. These are the signifiers of a city that is so young and has grown so quickly that there hasn’t been time to settle into any sort of architectural dogma.

“It’s an architecture that can only occur here,” Hernandez says. “We live in a place of intense migration and necessity, next to one of the richest states of the richest countries in the world — a place that disposes of a lot.”

It is exactly this landscape that inspires Hernandez’s work — multimedia projects that record her city’s improvised landscapes: retaining walls crafted from old tires, houses built out of cardboard and tarps, fences erected out of old wooden palettes, all of it detritus that often hails from the U.S.

In a series of projects that date back more than a decade, the artist has documented the city’s haphazardly constructed informal settlements.

“I was interested in how people use material,” she says. “And how those materials are used to re-create some element of the architecture of the place they are from. You see styles of houses from the coast or from the south of Mexico — but they’re all made with materials that are only found on the border.”

And through her images, she has recorded the ways in which Tijuanenses (residents of Tijuana) create order out of disorder, breathing new life into what others might consider garbage.

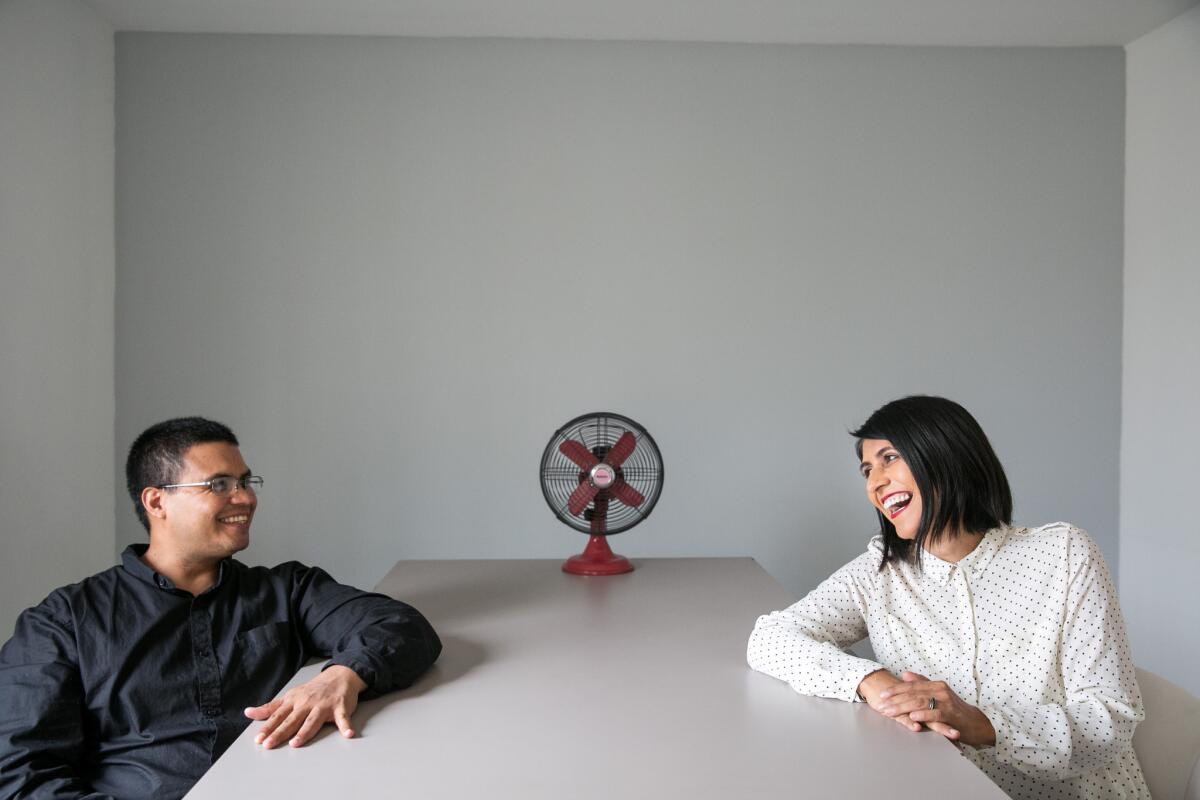

Hernandez was born and raised in Tijuana and operates the 3-year-old arts center Relaciones Inesperadas (Unexpected Relations) with her husband Abraham Avila, who is also an artist. The center, which offers seminars and talks geared at Tijuana’s expanding artist community, occupies a house adjacent to the couple’s own home.

Hernandez has shown her work in galleries and museums in the U.S. and across Europe. She also regularly travels abroad for residencies. But it is her native city’s unorthodox design that remains her most potent source of inspiration

Tijuana is a city that has grown in startling and unpredictable ways, from low-key ranching settlement to Prohibition-era party spot to booming manufacturing center alongside the world’s busiest border.

In 1950, Tijuana had a population of just over 60,000. Today, projections issued by the Mexican census organization estimate a population of nearly 1.8 million residents. Much of the growth is because of immigration from other parts of Mexico.

In fact, nearly half of the population in Baja California, the state where Tijuana is located, hails from elsewhere. Many residents flood the area to look for work — not just in the U.S. but in Tijuana proper, which is a major manufacturing hub for such items as medical devices and flat-screen TVs.

Housing, especially for the poor, hasn’t kept up with the flow, and as a result Tijuana is dotted with squatter settlements known as asentamientos. In these neighborhoods, homes are crafted out of whatever is at hand: garage doors, even the pressed cardboard panels that once lined the backs of old television consoles.

All of these elements are things that Hernandez has recorded in her work, which has taken her through a number of Tijuana asentamientos — some of which no longer exist. This has had the effect of making Hernandez’s photographs an important part of the city’s historical record.

But beyond capturing the city’s landscape and architecture over time, the images capture certain social realities too.

It is an intimate portrait of daily, domestic life among Tijuana’s lower economic rungs: the struggles, the transitory nature of existence in a squatter settlement, the ingenious ways in which migrants will build new lives for themselves.

“I work with houses,” Hernandez says. “But the pictures also tell the stories of people — of migrants, of the displaced. I want to show their conditions. That’s what I’m interested in.”

Hernandez has done numerous series in this way, in Tijuana and beyond.

In 2006, she traveled to Colombia and photographed dwellings belonging to people who had been internally displaced by the drug wars and the long-running guerrilla armed conflict. (She always shoots the homes, never their inhabitants.)

And in 2011, she captured spaces belonging to Mexican immigrants in New York City. “I was wondering if it was possible to talk about Mexican identity through objects and things,” she says.

Hernandez wiith her husband Abraham Avila at Relaciones Inesperadas, the small arts center they run in a building adjacent to their home in the Colonia Burócrata Ruiz Cortinéz in Tijuana.

But all of these projects, regardless of location, involve more than just taking pictures.

Hernandez sees her work as having an important social component. She meets with community leaders in the places that she photographs, she interviews the families whose homes she records, and she produces texts, books and videos that document the social conditions that serve as context for the photography.

“I always do the first exhibit locally,” she says. “I prefer that the community I work in be the first to see what I do.”

Next month, Hernandez will present some of her pictures at GuatePhoto, the annual festival in Guatemala that is one of the more prestigious photographic exhibitions in the Spanish-speaking world.

But she says she always likes to return to Tijuana.

“I like Tijuana because it’s quite liberal,” she says. “In other parts of Mexico, there is so much conservatism. But here you can do so much. It’s not finished being built.”

See more work by Ingrid Hernandez on her website ingridhernandez.com.mx. There is also a terrific interview with the artist in the English-language essay collection “Tijuana Dreaming,” edited by Josh Kun and Fiamma Montezemolo, and published by Duke University Press.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

Series: Tijuana’s Generation Art

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.