A tour through dark chapters of American history hits close to home at site of California internment camp

- Share via

Over the last month, I’ve logged some serious mileage across California for a story about race and the national parks that was published on Sunday. It explores the ways in which the National Park Service, a federal agency originally charged with protecting wilderness, has come to conserve places that have been the site of both contentious and inspiring incidents related to race in American history.

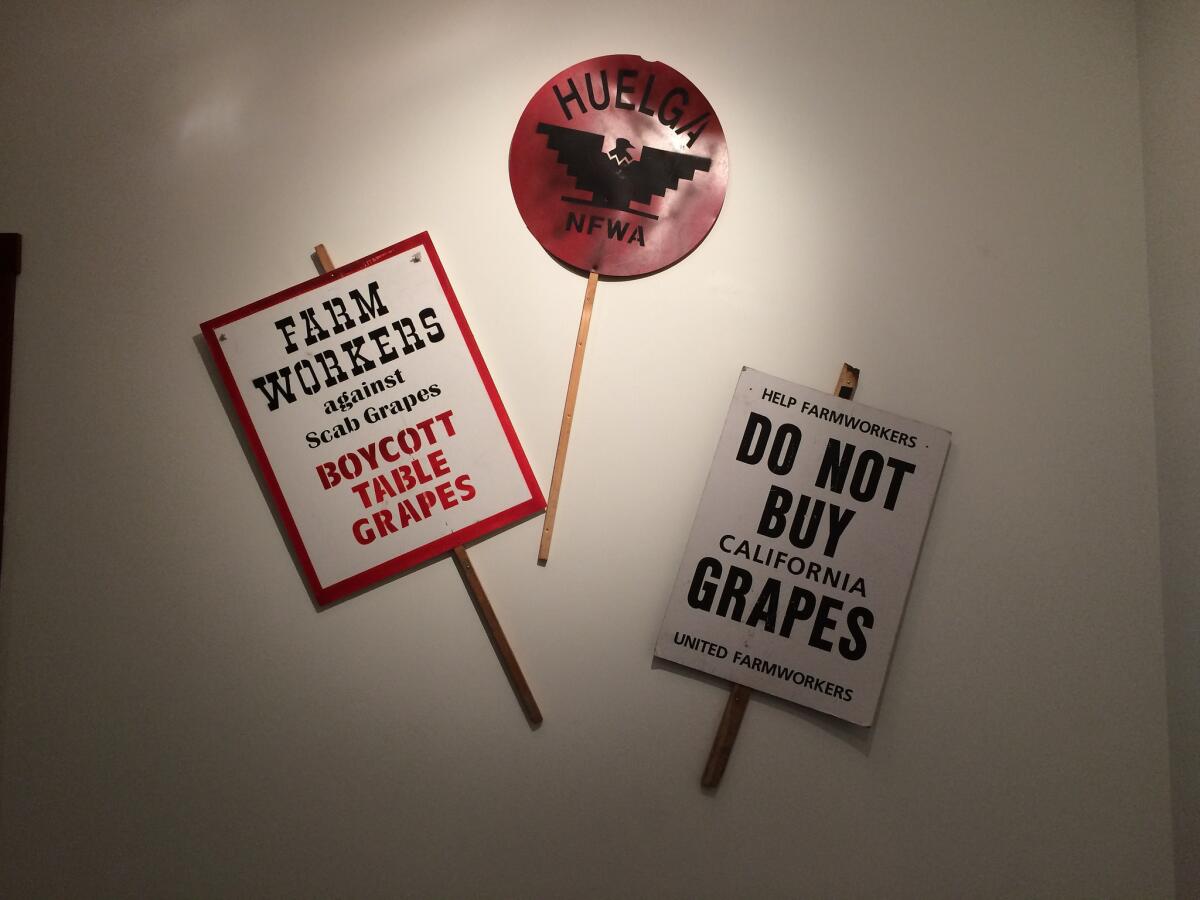

As part of the assignment, I toured the Port Chicago Naval Magazine outside of San Francisco and sat next to the graves of labor activists Cesar and Helen Chavez in the bucolic Tehachapi Mountains outside Bakersfield. I visited the sites of the former Japanese American internment camps at Tulelake and Manzanar.

On one of those journeys, I casually posted a photograph of an old theater on Tulelake’s main street on social media. My pal Nate Chinen, a New York-based jazz writer whose father was Japanese American, left me a comment: “This is the town where my father spent his first four years, in internment.”

When I saw it, my heart sank.

RELATED: Our national parks can also be reminders of America’s history of race and civil rights »

If you read about the histories of the National Park Service sites dealing with issues of race and ethnicity you will see a lot of numbers: Almost 120,000 Japanese Americans were interned during World War II. The average lifespan of a farmworker in the mid-1960s was 49 years, and the hourly wage was 90 cents.

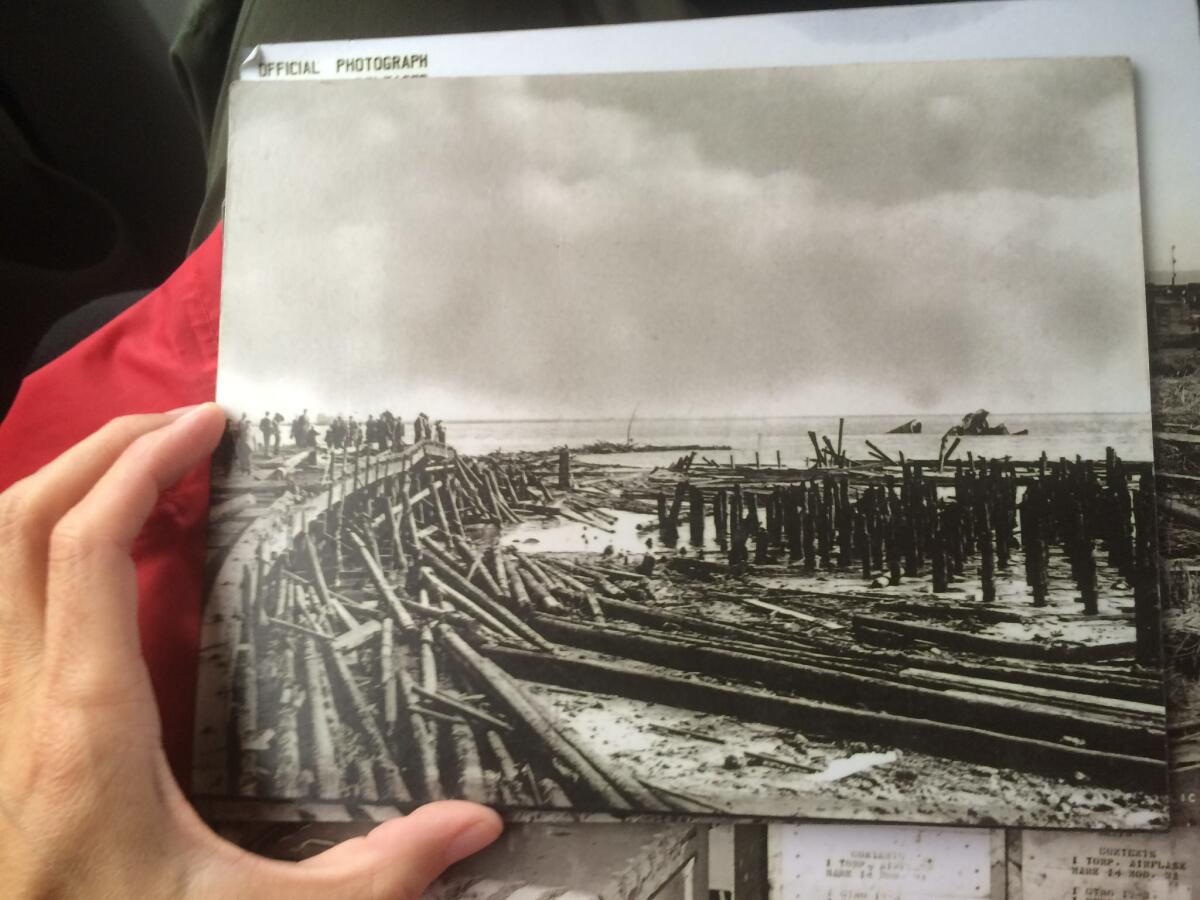

At Port Chicago, 320 men, mostly African Americans working in a segregated unit during World War II, lost their lives in a fiery munitions explosion — an accident borne out of the carelessness and disregard of naval commanders. The death toll represented 15% of the African American dead from World War II.

But taking the time to go to these sites makes these abstract figures come to life — connecting them to very real human stories.

At the Manzanar gravesite monument, where my only soundtrack was the wind and the gentle rustling of paper cranes left as tokens, I learned about the Japanese American woman who was buried there after dying in childbirth.

At Port Chicago, I found out about an African American man who was so traumatized by the magnitude of the explosion that incinerated his colleagues that he couldn’t stop shaking.

It is those individual stories that makes a visit to these sites so incredibly visceral. And given the political moment, so incredibly relevant.

I’ll never be able to look at my photos of Tule Lake without thinking of Nate’s dad — a toddler in a prison camp, his only crime to be born to Japanese parents.

Please read the story and check out the stellar images by Times photographers Francine Orr and Gary Coronado.

Herewith, a few images I wanted to share from my own journey:

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO:

Our national parks can also be reminders of America’s history of race and civil rights

Louis Kahn's Salk Institute, the building that guesses tomorrow, is aging — very, very gracefully

Review: Thrilling new exhibition shows modern Mexican art is bigger than murals

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.