EJ Hill stood on a podium at the Hammer for 78 days in a work about race, art and winning

- Share via

Over the course of this burning summer, the U.S. president met with the leader of North Korea, a Thai soccer team was rescued from a cave, Saudi women were allowed to drive, sexual harassment allegations that would bring down the head of CBS surfaced, Donald Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court and Tesla founder Elon Musk said a bunch of things.

Through it all, Los Angeles artist EJ Hill stood quietly on a winner’s podium inside a gallery at the Hammer Museum every hour that the museum was open — that’s 11 weeks or 78 days or 621 hours of standing, depending on how you do the math.

His piece, titled “Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria” — which translates to “Excellence, Resilience, Victory” in Latin — was part of the Hammer’s 2018 “Made in L.A.” biennial, which closed earlier this month. In it, he used symbols of sport to ruminate on the nature of sacrifice, competition and achievement.

A track circled the room and Astroturf carpeted the floor. To one side stood an impossibly tall wooden hurdle. Around the gallery, like stations of the cross, were stark photographs of Hill running “victory laps” around the schools he once attended: St. Michael’s Elementary in South Los Angeles, West High School in Torrance and El Camino College, also in Torrance.

Most riveting was the deceptively simple sight of Hill on the podium.

It’s hard being black, brown and queer. It’s hard to be alive in spaces that are designed to kill you. But there I am, still standing.

— EJ Hill, artist

The artist stood on his perch as mute observer but also as object to be observed by visitors who streamed through the gallery — visitors who, by popular vote, chose him to receive the biennial’s public recognition award, worth $25,000.

“We make these things, hoping that people pick up what we intend for them to pick up,” says Hill. “Most people get their arts education from going to museums and seeing art on their terms … For them to say, ‘Hey man, good job, we love this,’ feels like I can say with confidence that I am making work for the people.”

On the day after his summerlong vigil has come to an end, Hill welcomes me to the South Los Angeles home of his mother, Karen Thompson. They are having breakfast — scrambled eggs, beans and the spongy Belizean frybread known as a fry jack. (Although Hill was born in Los Angeles, his family hails from Belize.)

Padding around in shorts and a pair of socks decorated with palm trees, Hill has shaken the look of far-off intensity, sometimes pain, he would demonstrate in the gallery at the Hammer. Here at home, he is relaxed.

At moments, however, he grows slightly dazed, like an astronaut who has just reentered Earth’s atmosphere after a journey through space.

“We’re talking about this in the past tense,” he says of his performance with a jolt of surprise. “That’s nuts. I can’t believe that this thing is behind me.”

For months, his life revolved around nothing but the podium.

“It was kind of a monastic existence,” he says. “I would come home and just eat and go to sleep. Right now, I feel really resolved, centered and light.”

Thompson says her son would frequently come home exhausted.

“I was, like, ‘Why can’t you just do this for an hour’?” she says good-naturedly. But she says she came to understand that a performance about perseverance would require, well, perseverance. “The first month, I’d go pick him up at the end of the day and I’d get there 15 to 20 minutes early and just watch him.”

Now that performance is done.

“I missed a lot,” Hill says with a laugh. “I’m catching up on things. I went to see ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ — so, going to the movies. I was reading the Kavanaugh hearing stuff. Everything feels so surreal.”

Throughout the summer, I checked in on Hill’s performance, repeatedly drawn in by the topics it explored, its fraught symbolism, its stubborn steadfastness.

When I first entered the gallery in June, he was dressed all in black, looking defiant, ready to face the weeks that lay before him. Over the course of the exhibition, the performance evolved.

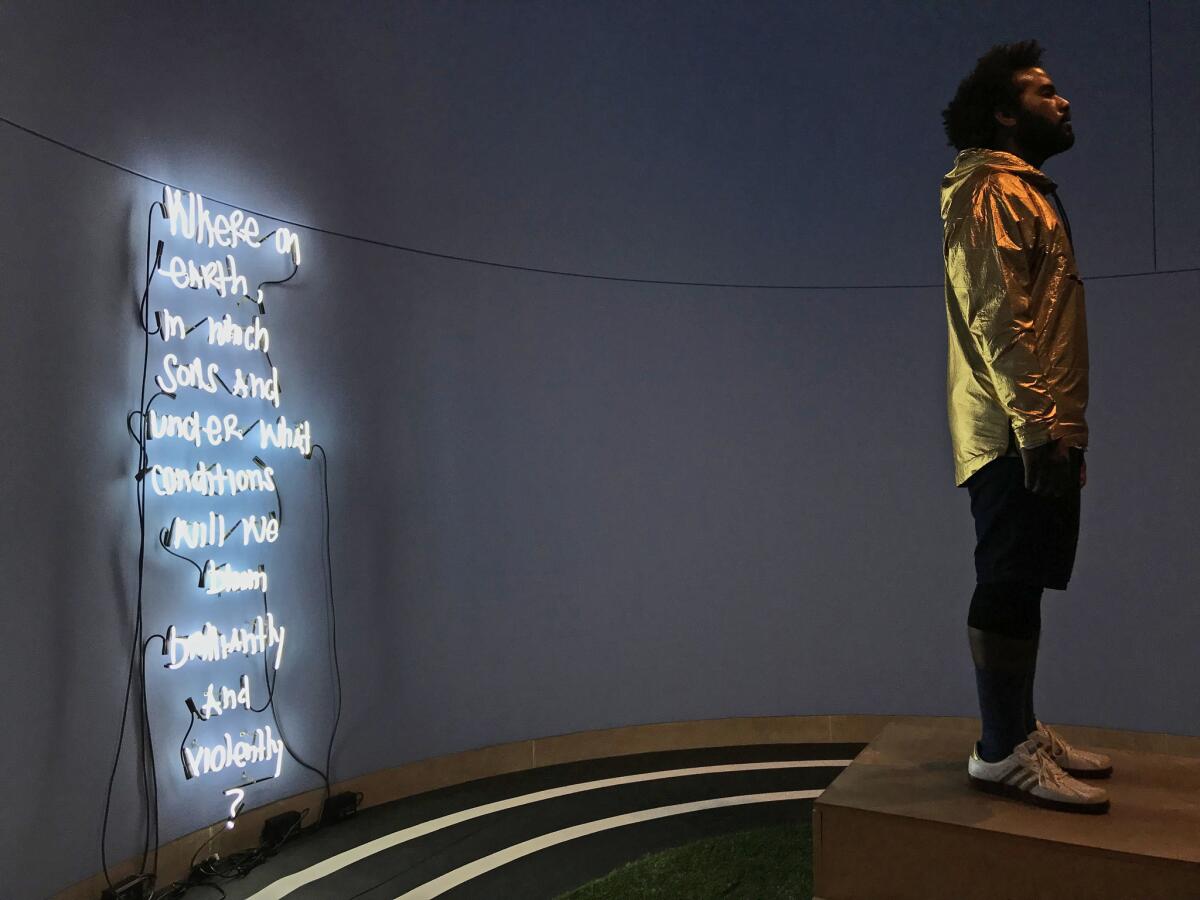

In July, he wore white; by August, he was rocking a metallic gold sweatshirt, looking like an interstellar voyager ready to float into space. On some days, he seemed light, on others, he appeared to be willing himself to continue.

“I called them phases,” he says. “The white, that was like, ‘My body has settled into this, my mind has settled into the routine. The day is long but I don’t have to answer emails.’” A wry laugh spills out.

The reaction of viewers seemed as much a part of the piece as the performance itself. Many visitors to the gallery avoided looking directly at Hill, casting only furtive glances in his direction. Hill says he had people jab at him to see if he was real.

“One older couple came in and the guy was, like, ‘Do you get it?’ and she’s, like, ‘No!’ So they leave,” he recalls. “They were there for, like, 10 seconds max. That was so funny to me.”

But those who lingered were rewarded with something profound.

Hill had placed his body on a podium as an object to be evaluated — the hyper-scrutinized black, male body in a position to be scrutinized further still. To be a fair-skinned woman walking around that podium gazing at his legs, his arms and his chest was to feel complicit in our historical objectification. The black body scrutinized as vehicle for sport. The black body scrutinized as vehicle for labor. The black body on a podium. The black body on an auction block. One afternoon in the gallery, I found myself in tears.

Hill says many visitors to the gallery cried.

“People connect with what it feels like to want to completely throw in the towel,” he says. “This isn’t our game. We’re in this thing that wasn’t designed for us. It still grinds on us … It’s hard being black, brown and queer. It’s hard to be alive in spaces that are designed to kill you. But there I am, still standing.”

Running laps

At its core, “Excellentia Mollitia, Victoria” is about Hill, 33, reexamining the places that have shaped him and reckoning with their significance to his life. The work began as a sketch that he produced early last year, shortly after returning home to Los Angeles after time in Boston and New York (where he was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem).

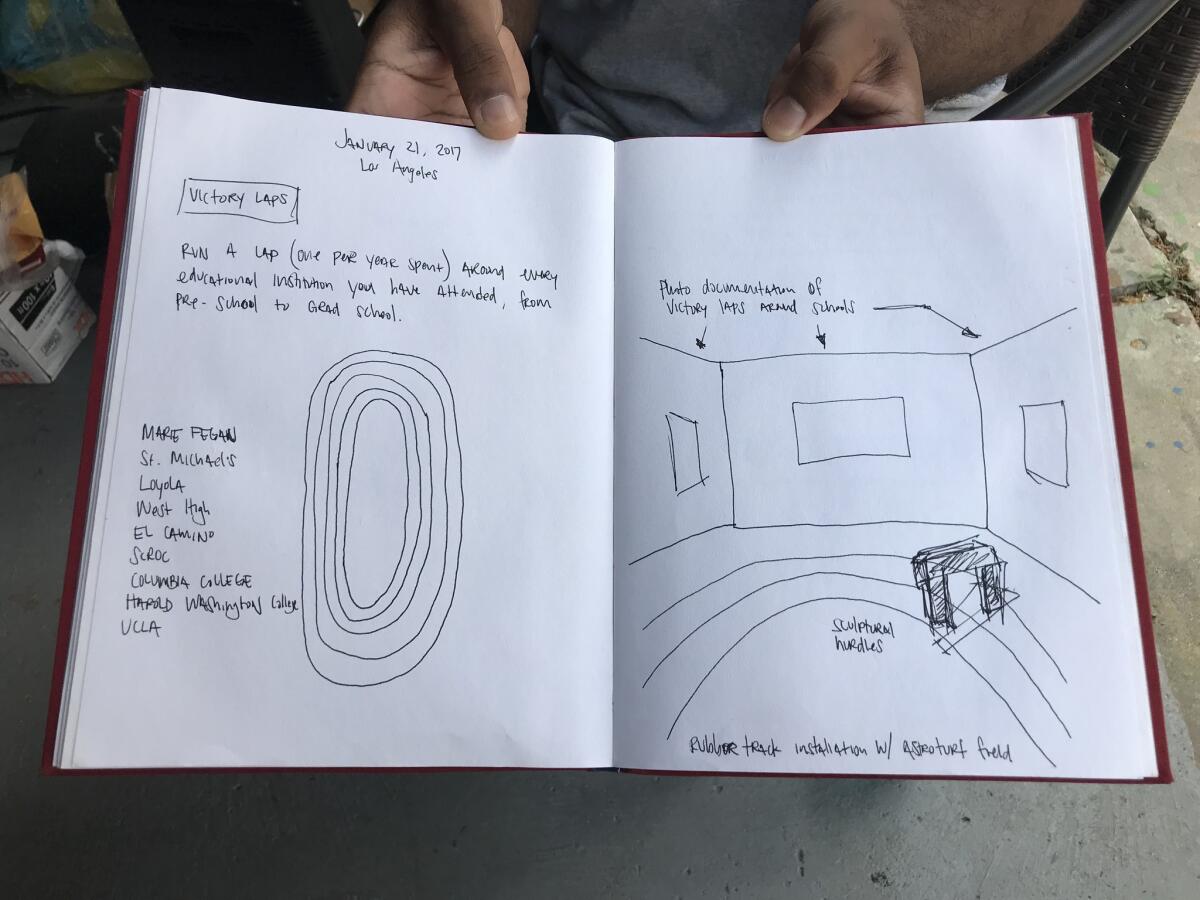

Hill leads me out back to his mother’s garage, which serves as his studio. Boxes and plastic crates are strewn about. There is a handful of drawings pinned to the wall. He digs around and produces a notebook and opens it to the corresponding page. It shows a running track and a hurdle. An adjacent text reads: “Run a lap (one per year spent) around every educational institution you have attended.”

When curators at the Hammer Museum came calling for “Made in L.A.,” Hill pitched them the idea. They said yes.

He began by running around the various schools he had attended in Los Angeles, actions elegantly recorded by photographer Texas Isaiah. “On each lap around the block that each campus is on, I would really think about who that teacher was at that time and what that meant in my life,” Hill says. “There were some laps that were really difficult.”

The actions acknowledged education as empowerment but also as something to be overcome, of the ways in which African Americans are welcomed — and not — into U.S. institutions. In this case, an educational system that claims to aspire to diversity even as it writes black history out of the textbooks.

“I have been trying to grapple with what it means to be included in spaces we’ve been taught to strive for,” Hill says. “The better neighborhoods or the better schools.”

“Is it possible to design these spaces with the best intent?” he asks. “Rather than replicating the power structure that we’re trying to dismantle?”

Just as powerful was the symbol of sport. The motif channeled one of the few avenues of success open to African Americans in the 20th century. On the floor lay a wooden torch — evocative of competition but also of hate.

“The Olympic torch, it’s one thing,” says Hill, “but if you put that torch on someone else’s front lawn, it means something else.”

Throughout the course of the exhibition, visitors to the galleries frequently tripped or stepped on the torch, like a shameful piece of history that continuously reemerges as physical irritant.

Reaching the podium

The performance, however, was not without humor.

One of the schools Hill attended was UCLA, where he received his master of fine arts degree in 2013. Of his experience there, he remains ambivalent. Like most MFAs, the degree is supposed to be about art and its ideas. But like many MFA programs at prestigious universities, the competitiveness of the art market seeps into the program.

“Culver City galleries were breezing through our studios,” says Hill. “And there’d be the talk of, ‘So-and-so sold out their open studio.’

“There’s this competition in art to become something. If you think of rappers, the whole persona of ‘I’m No. 1’ — within art, it’s very much present, but you’re supposed to be coy about it.”

Hill decided not to be coy. He placed himself on the podium slot reserved for the gold medalist.

“I knew it was a bold move to put myself in first place and just claim that,” he says with a smile.

And certainly, to stand beneath Hill in the gallery, elevated on his winner’s perch, was to gaze at a figure who was larger than life.

The artist’s original plan had been to run laps around UCLA once the performance at the Hammer was complete. But he says the experience left him feeling resolved.

“I’ve seen all of the people who were part of that experience all summer, so I’m good.”

Now he is working on his reentry into everyday life. The day after completing his performance, he was scheduled to fly to Boston to begin a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University.

“It was a very extreme remove,” he says. “I got to spend beautiful moments in that room with complete strangers. But now I’m back on the hamster wheel.”

ALSO

Why Luchita Hurtado at 97 is the hot discovery of the Hammer’s ‘Made in LA’ biennial

‘Made in L.A. 2018’: Why the Hammer biennial is the right show for disturbing times

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

[email protected] | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.