Art after Fidel: What Castro’s death means for a rising generation of Cuban artists

- Share via

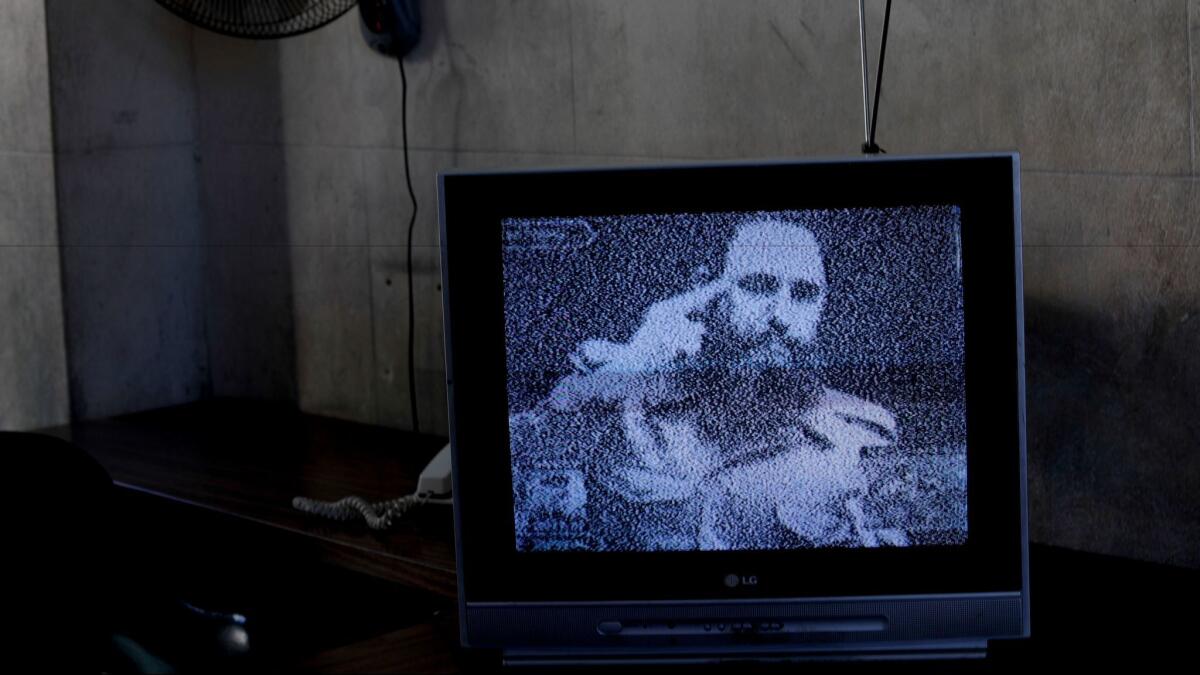

Ever since he was sidelined by illness from his role as Cuba’s leader in 2006, Fidel Castro loomed like a historical shadow. El barbudo (the bearded one), as he was known, was present in the occasional staged photograph or rambling newspaper editorial but no longer a part of daily life in the country he had micromanaged since the revolution he led in 1959. (Castro, quite famously, involved himself in everything from sugar harvests to cow breeding.)

But his death last week at the age of 90 nonetheless marks a titanic turning point for Cubans. Among them: The country’s artists. For nearly six decades, culture has been tightly controlled by the government, both through patronage and censorship. And even though Castro’s death may not bring immediate liberties to artists in search of free expression, it does mark a tremendous psychological milestone.

“It’s really an important moment,” says independent curator Dan Cameron. The former Orange County Museum of Art chief curator has been traveling to Cuba for more than two decades and was in the country last year to conduct research for one of the Pacific Standard Time exhibitions to be held in Southern California next year.

“[Castro] was the most potent living symbol of the revolutionary period of the 20th century — and not just for Cubans,” he explains. “For many Latin Americans, for people around the world, including people who were born many decades after the revolution happened, he is a really important symbol of defiance.”

And Castro’s continuing presence, however slight in his declining years, still held a psychic weight.

“There has been a resistance to change, whether consciously or not, as long as he was taking breath,” adds Cameron. “But with his death, it’s hard to imagine that things will stay the same.”

None of this means that freedom of expression is going to blossom in Cuba overnight.

It will take some time for all of this to get sorted out on the level of actual culture — not commerce.

— Norberto Rodriguez, artist

In fact, on Saturday, Cuban dissident artist Danilo Maldonado Machado, known as “El Sexto,” was reportedly taken into custody by the authorities after celebrating Castro’s death on social media. Moreover, the authorities have banned live music and alcohol around the country during an official nine-day period of mourning (to the dismay of international tourists).

Tania Bruguera, a Cuban-born artist who was detained on multiple occasions by authorities in Havana early last year after attempting to stage a performance about free speech, notes that though Castro is gone, his brother Raul, who has managed the country for the last decade, is still firmly in charge.

“We will have to wait and see,” she stated via email from Cambridge, where she is on a fellowship at Harvard University. “Raul has demonstrated to like secrecy, closed-door negotiation meetings and not sharing with his people or even with the press what he is doing.”

Darrel Couturier, of L.A.’s Couturier Gallery, who has represented Cuban artists in Southern California since the 1990s and travels to the island regularly, concurs. “I don’t think any immediate changes will happen,” he says. “The government is more or less the same.”

Bruguera, a Cuban national who divides her time between Cuba, the U.S. and Europe, is in the midst of staging a satirical, long-term performance piece that comments on the lack of democracy on the island: She recently announced that she is running for president of Cuba when Raul steps down in 2018 — a futile act in a one-party state that doesn’t hold presidential elections.

Fidel’s death, she says, gives the topic greater urgency.

“I think it is more pertinent than ever to exercise the right to access power by anyone who wants to make some change,” she writes. “It is a good civic exercise to think you can have something to say in the new view of Cuba.”

Although change may not happen overnight, it is nonetheless afoot — and has been for some time. Fidel’s slow fade from the public eye and Cuba’s ongoing social and political opening, including the reestablishment of diplomatic ties with the U.S., has already led to shifts in how artists operate and how art is made.

“I don’t think the themes addressed in contemporary Cuban art are as focused on the political and social conditions as they were, as [Castro] once defined them,” says Couturier, who is currently showing the work of a trio of contemporary Cuban artists in his gallery. “Cuban artists have gone and moved on to a more international community and become a part of the world.”

Cameron, likewise, has worked with a number of Cuban artists who live and work internationally, including Bruguera, sculptor Alexandre Arrechea and the collective Los Carpinteros — all of whom have shown at major museums around the U.S.

“You have these artists who are used to working in Europe and traveling around the world and they to go to Florida and they work in United States,” he says. “Coming back to Cuba, coming face to face with the absence of freedoms in their home country, makes it more unsustainable over time to maintain a lack of freedom.”

For specific artists, he adds, the situation is even more delicate.

“If you look at Tania Bruguera’s situation — the face-off she had with the state security apparatus,” Cameron says “something like that starts to look really unsustainable after Castro’s death.”

If restrictions do continue to loosen, Cuba could be the site of an unparalleled cultural renaissance — of the type that has occurred in other countries where long dictatorships have come to an end. This includes Spain at the end of Francisco Franco’s nearly four-decade reign, which saw a rush of film production after the lifting of moralist codes that barred nudity, and Chile in the wake of the regime end of Augusto Pinochet, where a renewed attention to urban design helped transform the country into a center for architectural innovation.

Norberto Rodriguez is a Cuban American artist based in Los Angeles who traveled to Cuba last year as part of a cultural exchange program.

“Artists have been living with the presence of Castro for 60 years,” he says. “It’s more than a lifetime for most artists, some of whom are really young.… This guy has taken that space for so long that we don’t know a world without that space being occupied — none of us do.”

But with Castro gone, Cuban artists across the board — not just the ones who globe trot — may feel freer to explore new terrain.

“Culture hasn’t been allowed to thrive,” says Rodriguez. “Until now, you’ve had artists working with two hands and two legs tied behind their back. But that is going to change. You have some brilliant artists who have the potential to affect culture in a really universal way, to move culture forward.

“In 15 or 20 years it could be like Paris in the ’20s. But it will take time. And of course there will be a bunch of curators and gallerists and collectors who are going to go down there and grab whatever they can grab. Artists will have to navigate that. And it will take some time for all of this to get sorted out on the level of actual culture — not commerce.”

We are dealing with a wild card here.

— Darrel Couturier, Couturier Gallery, on Donald Trump effect on Cuba

At this moment in time, all of this remains speculative — since no one knows if Raul Castro will actually retire in 2018 as he has indicated he might, and no one can be sure that his retirement will be followed by the implementation of a democratic system or greater freedom of expression.

There is also the very big question of President-elect Donald Trump, who, in the wake of Fidel’s death, threatened to roll back some of President Obama’s measures to establish full relations with Cuba.

“We are dealing with a wild card here,” says Couturier. “It’s a complete unknown to everybody.”

But Cameron says that regardless of what Trump threatens to do, Cuba is likely to remain on a path to greater openness — especially in the arts, which draws audiences to the island not just from the U.S., but from all over Latin America and Europe.

“After São Paulo, the Havana Biennial is one of the most important exhibitions in the Western Hemisphere,” he says. “The genie is out of the bottle. And there is nothing Trump can really do that will change that.”

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO:

Fidel Castro dead at 90: The revolutionary icon’s influence was felt far beyond Cuba

The late Cuban artist Belkis Ayón’s mysterious world unfurls at the Fowler Museum

‘Cultural feeding frenzy’: Art world descends on Cuba for Havana Biennial

Review: Thrilling new exhibition shows modern Mexican art is bigger than murals

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.