Southern California orchestras sound a hopeful note

There is more bad news in orchestra land.

On Friday night the Spokane Symphony went on strike. Members of the Minnesota Orchestra in Minneapolis and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra continue to man picket lines. All this is on top of the recent budget woes and musician disharmony in Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, Atlanta and Indianapolis that have begun to define orchestral life.

Could this finally be the end of the line for the history of the greatest noise-making machine in history?

That is how the La Jolla Symphonyâs music director, Steven Schick, described the symphony orchestra at his concert on Sunday. His orchestraâs concert was one of three I attended in Southern California over the weekend that tell a more hopeful story about the prognosis for orchestral health in modern times and in communities, from Pasadena to Los Angeles to La Jolla.

SPECIAL REPORTS: Fall Arts Preview

Orchestral â to say nothing of orchestrated â doomsday prophecies go back to the early 19th century, when orchestras lost court patronage and began playing for an unwashed general public. Beethoven was blamed for killing the symphony with his cacophonous âEroicaâ; Mahler, for massacring it with his wild symphonies; Stravinsky, for suffocating it with his âRite of Springâ a hundred years ago.

When NBC put orchestras on radio, predictions were that concert halls would go out of business. The talkies meant that the movies would finish off serious symphonic music.

Leonard Bernstein going on TV was the last straw. Then pop culture was the last straw. Now itâs the Internet, stupid.

MUSIC COVERAGE: Classical, opera and jazz

Yet for two centuries what didnât kill orchestras made them stronger. And just to make sure that could still be true in the Great Recession, I began the weekend by taking the pulse of the Pasadena Symphony at its Saturday matinee. That evening, I moved on to the big kahuna, Los Angeles Philharmonic at Walt Disney Concert Hall. Then Sunday I drove to La Jolla for the UC San Diego -affiliated semi-professional community orchestra.

The Pasadena Symphony happens to be the orchestra I grew up with. It attracted a traditional white-haired audience at that time, when Pasadena was belittled for its âLittle Old Ladies.â It was decidedly not a young nor hip scene.

It still isnât. The orchestra is in its second season playing in the acoustically intimate Ambassador Auditorium on the edge of Pasadenaâs swarming Old Town, but sometimes seeming a world away from the hubbub.

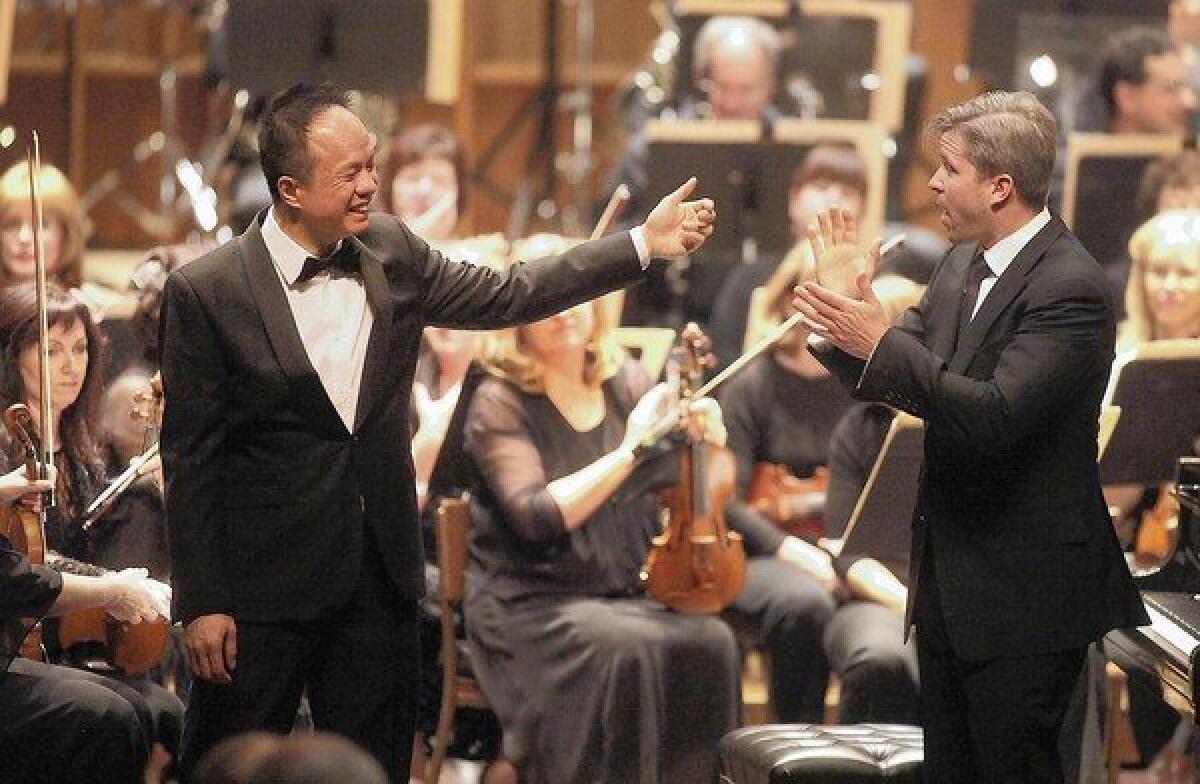

The orchestra is also in its second season without a music director. The guest conductor Saturday was Edwin Outwater, 41, a Santa Monica native and music director of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony in Ontario, Canada. The program was conventional â the Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and Tchaikovsky Fourth Symphony.

Joining the orchestra as soloist was a Taiwanese pianist, Rueibin Chen, who is a competition champ. His biography in the program book noted 18 international metals, five of them gold. He has very fast fingers and a fine publicity machine.

But the real interest was in Outwater, especially if he is a candidate for the orchestraâs music directorship. Outwater has made an exciting recording with his Canada orchestra of works by Radioheadâs Jonny Greenwood and of the young American composer Nico Muhly.

But there was nothing modern on the program, which began with Li Huanzhiâs âSpring Festivalâ Overture, a 1956 Chinese crowd-pleaser.

Outwaterâs performance of Tchaikovskyâs Fourth Symphony sounded fascinatingly contemporary. Lean, tight and transparent, this Tchaikovsky sizzled with inner life. The playing was clean, the horns a pleasure.

If Outwater could transform fate-hounded Russian Romantic symphony into something verging on optimism, might that not happen with an orchestra too? I walked to Old Town after the concert for a cappuccino and, for once, felt the connection.

The L.A. Phil does not have to worry about seeming relevant, it fills its halls and does a decent job with its budget by keeping current, by mixing standard repertory with the new. This night the orchestra, too, had a Tchaikovsky Symphony on the bill â the Sixth (âPathĂŠtiqueâ). But it also had a recent work by Osvaldo Golijov, perhaps our most charismatic contemporary composer (if, these days, one apparently affected by writerâs block).

Marin Alsop, herself a groundbreaker in her significant chipping away at the glass ceiling for conductors, was on the podium. She began with Samuel Barberâs Second Essay, which I will leave Barber admirers to evaluate.

A young cellist, Joshua Roman, who likes to be dubbed as âa classical rock star,â was soloist in Golijovâs âAzul,â his 25-minute cello concerto that also includes an electronically enhanced hyper-accordion (Michael Ward-Bergeman) and two solo percussionists (Jamey Haddad and Keita Ogawa).

Yo-Yo Ma, for whom the score was originally written, brought more intensity to âAzulâ when he gave the West Coast premiere with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra in 2009, but the piece conveys such a sense of rapture that the audience went comfortingly crazy anyway.

In Tchaikovsky, Alsop â who was on the news that day for having had her studio in Baltimore (where she is music director) damaged by Hurricane Sandy â showed herself to be something of a force of Mother Nature herself. Hers was a âPathĂŠtiqueâ loud and rhythmically aggressive, with brass blaring in a symphony usually heard as Tchaikovskyâs farewell to life.

If Alsopâs was much more a power-trip Tchaikovsky than Outwaterâs, she, too, left a listener in high spirits. Even so, she took no chances of a hint of depression by adding the jaunty Brahms Hungarian dance as an encore, highly unusual for the situation.

The La Jolla Symphonyâs program began with the West Coast premiere of Missy Mazzoliâs âViolent, Violent Sea,â which couldnât have been more timely, given that the young composer lives in Brooklyn. It is a beautiful, moving and memorable 10-minute score, in which the violence is a subtle hint of trouble, usually from the brass, under an alluringly placid surface.

The half-century-old orchestra is composed of a mix of amateurs and professionals. The Sunday matinee audience in UCSDâs Mandeville Auditorium seemed older than even Pasadenaâs (joined by only a few students). But this is no old-fashioned orchestra. In his five seasons as music director, Schick, who is a percussionist and leading exponent of new music, has created the most daring orchestral programs in the country.

The inspiration of this one â which included Cageâs 12-minute anarchic and sonically effusive â101,â for 101 players, and âAriaâ (thrillingly sung by Jessica Aszodi) â was to introduce Beethovenâs âEroicaâ with Cageâs â4â33â.â After four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, the opening of Beethovenâs symphony, which we can take for granted, sounded once more revolutionary.

The âEroicaâ performance was pretty funky in places (many places), but it also felt compellingly contemporary. One man behind me shouted âwonderful,â over and over, at the end.

This may not be a wonderful time for orchestras everywhere, and not all will weather their current storm. But the wonder in orchestral life, like amazing mushrooms after a downpour, remains a renewable, life-giving resource. You only have to look in the right place.

MORE:

CRITICâS PICKS: Fall Arts Preview

TIMELINE: John Cageâs Los Angeles

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.