In Theaster Gates’ latest work, poignant power from the remnants of our history

- Share via

Theaster Gates recycles — or transforms — just about everything he gets his hands on. And some things he doesn’t.

At Regen Projects, the Chicago-based artist starts with the stuff he finds in his hometown, transforming worn-out fire hoses and the floorboards of basketball courts from shuttered public schools into large abstract paintings that seem to be haunted by ghosts — and all the more poignant for it.

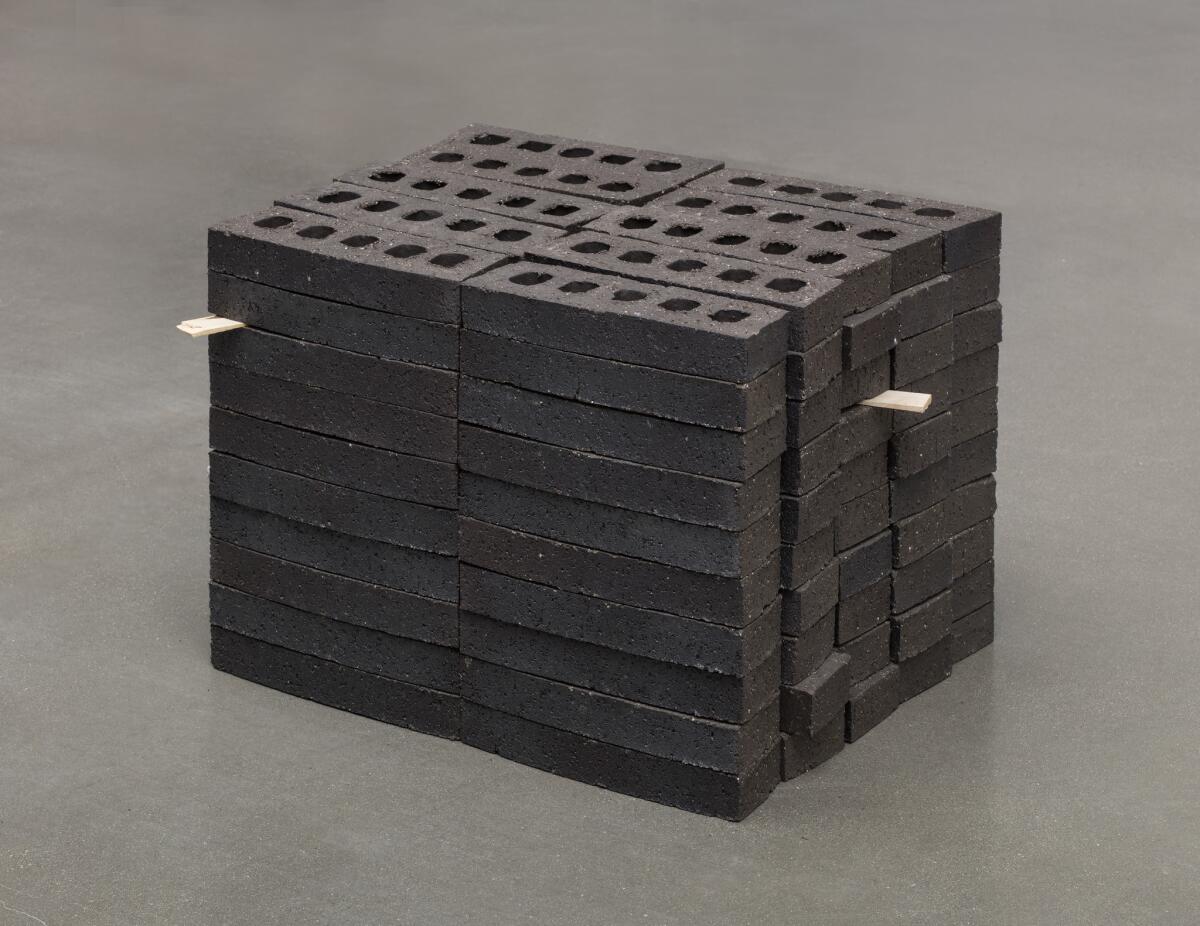

Gates also takes clay, leftover from an industrial manufacturer, and adds manganese to make sturdy bricks that will be used to construct various shelters and gathering places, their metallic sheen glistening with possibility, real and anticipatory. Stacked on the floor of the gallery, the black bricks play fast and loose — and very effectively — with Minimalism’s insistence on keeping art simple: whitewashed of context and stripped of associations that might be poetic.

Research journals provide Gates with graphs and charts, which he uses as compositional elements in the geometric abstractions he paints on aluminum panels.

The original significance of the diagrams is lost in translation. That loss is palpable. And that is part of the point of Gates’ crisp compositions: No message — or way of speaking — says everything. The idea that abstract art is timeless and pure gets thrown out the window.

From libraries that are going digital, Gates collects Jet and Ebony magazines. He binds them in thick volumes and lines the volumes up, bookshelf-style, on the wall.

In gold letters on the books’ spines are printed single lines of Gates’ poems. Each poem turns everyday language into a dance and a dagger, a multilayered incantation that is searing and sensitive, lovely and loaded. Gates’ words deliver insight and mystery as they make sparks fly in the mind’s eye.

His virtuosity as a recycler comes into focus in a video of him singing the first stanza of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” Accompanied by a keyboardist and a percussionist, Gates sings the patriotic ditty three times.

The first is jaunty, upbeat, even cheeky. Almost bombastic, but a little too speedy, it feels fake, as if Gates is going through the motions because the words coming out of his mouth don’t speak to him.

The next version is gentler. But coy. Gates’ body language, and the song’s tone and tempo, suggest an uncomfortable relationship between the song’s claims — of liberty and freedom — and the reality we inhabit.

The third time through, the tables turn. Gates sings as if liberty and freedom are dreams he just might believe in. Because the alternative is worse. He repeats lines, both for emphasis and because he is wonderstruck by the possibility of it all.

What Leonard Cohen did for “Hallelujah,” Gates does for the song that was the de facto national anthem from 1831, when it was written by Samuel Francis Smith, until 1931, when “The Star-Spangled Banner” replaced it. He makes ideals intimate. Grand aspirations come down to earth, where we experience them face-to-face.

Starting with fire hoses and floorboards, moving onto words and symbols and songs, Gates includes visitors in the list of things he transforms. His exhibition is a gift.

Regen Projects, 6750 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles. Through Feb. 25; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 276-5424, www.regenprojects.com

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

In L.A. march, Grand Park performs well with huge crowds; Metro and Pershing Square, not so much

Artists speak out on why they joined the march for women

A free comic offers artist ‘Resist!’-ance at the Hammer Museum

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.