Critic’s Notebook: The ‘L.A. Phil Effect’ hits New York, Cleveland and beyond

- Share via

Reporting from New York — America’s oldest and most famous orchestra may call New York home, but when the Philharmonic recently opened its 176th season, it was with a notable nod to Los Angeles.

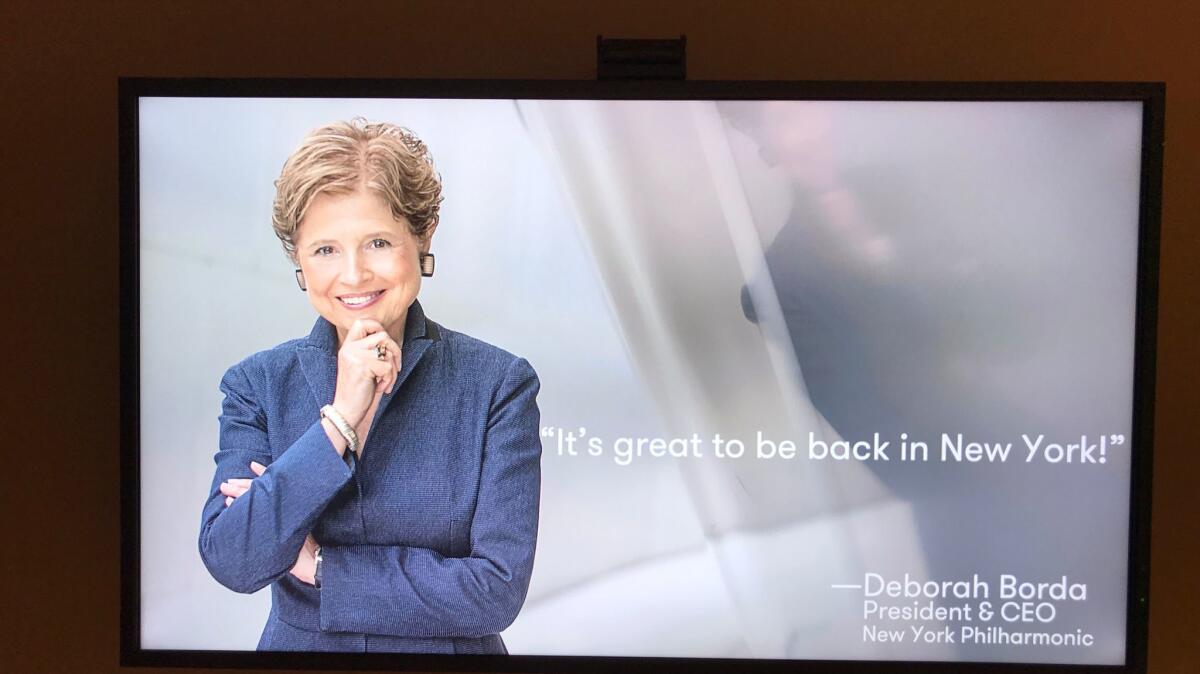

If you entered the side entrance of David Geffen Hall for the New York Philharmonic’s first regular concert of the season, the first person you saw projected on a video screen was not the orchestra’s newly appointed music director, Jaap van Zweden, but its new president and chief executive, Deborah Borda, just arrived after 17 years as head of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. And she was not posed by the Lincoln Center fountain but in front of Walt Disney Concert Hall — a photo, also used in the program book, that seemed to send a subliminal message.

Sure, there was once an East Coast attitude of belittling the arts in La La Land, the Land of the Plastic Lotus, or whatever. But that’s as old as an early Woody Allen film. Indeed, Los Angeles has been a mecca for classical music since the 1930s, a place where art can invent away from, as well as absorb, old-world traditions. (Let’s not forget that even Allen, with witty irreverence and a wink to Hollywood, directed an opera in — and only in — L.A.) For fresh proof of just how stale those old pop-culture stereotypes have become, look to the new classical season.

No one should be surprised that L.A. and the L.A. Phil have begun exerting unprecedented influence around the country.

The New York Philharmonic concert began with Philip Glass’ Concerto for Two Pianos, which happened to have been commissioned and premiered by the L.A. Phil two years ago. This week, the New York Philharmonic devotes itself to Hollywood’s most renowned composer, John Williams, performing some of his “Star Wars” soundtracks to screenings of the films.

But the “L.A. Phil Effect” is not just in New York. The Cleveland Orchestra opened its centennial season by remounting its 3-year-old “only in Cleveland” production of “The Cunning Little Vixen,” a fanciful opera about a fox that wondrously incorporates animation with live singers and instrumentalists. The director is Yuval Sharon, founder of the L.A. opera company the Industry and artist-collaborator of — what else? — the L.A. Phil.

No one should be surprised that L.A. and the L.A. Phil — the most important orchestra in America (so says even the New York Times), the most prosperous (so say the annual reports) and the most ambitiously imaginative (so says program after program) — have begun exerting unprecedented influence around the country. Borda, in particular, clearly plans to bring as much L.A. ingenuity to the New York Philharmonic as she can get away with, restoring the bold image it had when it was the orchestra of Mahler, Toscanini, Bernstein and Boulez.

That means first of all solving the past, present and future conundrum at Lincoln Center, which has spent millions on architectural plans over the years to renovate its cumbersome, unloved concert hall. None has come to anything.

She also must find a way to make the orchestra the talk of the town again. It hasn’t had a star conductor as music director since Zubin Mehta arrived from L.A. in 1978.

Borda has decorated her new office with personal mementos, most from L.A. In one, music director Gustavo Dudamel comically signed a photo as her devoted husband in response to a society photo caption in the L.A. Times that mistakenly referred to the pair as Mr. and Mrs. Dudamel. But she also has reminders of what the New York Philharmonic once had been, such as a glamorous photograph of Leonard Bernstein at the piano that dominates one wall.

“I’m a different person, and the Philharmonic’s changed,” Borda said, explaining why she thinks the orchestra is ready to move forward.

“If you look at an institution that has survived for 176 years, the times it has truly flourished have been the moments when the institution has been most innovative — the first American orchestra to tour Europe, the first orchestra to do TV, etc. It was a leader, and it can be a leader again.”

That she has a multimillion-dollar deficit to contend with seems to worry her but a little. She inherited the same when she first got to L.A., and by the time she left, the L.A. Phil had a $120-million balanced budget that was more than 60% larger than New York’s. Her philosophy then, as now, was not to “cut your way health” but to beef up a staff that’s needed “to market, raise money and dream.”

Nor does she fret that the stern 56-year-old Van Zweden, who has one more season to go with the Dallas Symphony before officially beginning in New York, doesn’t exactly cut a romantic figure and hasn’t had the warmest welcome from the press or the music community.

He has a reputation for being so demanding, he can drive hardened orchestra musicians to tears. He is known for powerful performances of standard repertory, not for vision.

That, Borda said with a sly laugh, allows her to exploit low expectations. The hard-as-nails orchestra apparently relishes a conductor with grit and had a say in selecting him. Borda insisted that in getting to know Van Zweden, she has found the kind of flexible and unexpectedly funny partner that Esa-Pekka Salonen and Dudamel were for her in L.A.

During the Glass concerto — with (as in L.A.) the Labèque sisters Katia and Marielle as soloists — and Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, there was no question that Van Zweden did the trick of getting New York’s generally stone-faced musicians to appear downright jubilant, as though taking a page from the happy L.A. Phil players in Disney Hall. The audience seemed just as newly energized as the orchestra.

But the ambience in Geffen was nonetheless most un-Disney. A secret to Borda’s success in L.A. was her capacity to create a sense of community, and she had the right hall in which to do it. She sat among the audience. People constantly came up to her to show appreciation or kvetch or ask questions. In Disney Hall, composers and celebrities sit among ordinary listeners. A soloist might join your row for the second half of the concert. It begins to feel like a family.

In Geffen Hall, a critic or patron couldn’t ask Glass about changes he made in his concerto, because he was tucked away in a box — as was Borda. The orchestra here puts on a show from on high, as apart from the audience as actors on Broadway playing a role.

In Cleveland, the orchestra plays in Severance Hall, an ornately old-fashioned place that was renovated to its former glory a decade ago. Tradition seems to inhabit every square inch.

That hasn’t, however, stopped Cleveland from turning to an L.A. talent for new ideas. At the L.A. Phil and as leader of the Industry, Sharon is notably reinventing the operatic wheel, such as in the 2015 opera “Hopscotch” performed in vehicles traveling in and around downtown L.A.

For Cleveland’s “Vixen,” Janácek’s nature opera with characters both animal and human, Sharon called upon animation by Walter Robot, as lovable as Walt Disney but without the fake fantasy, projected on three screens surrounding the orchestra. Masked singers popped their heads through the screens. Musically, the performance wondrously captured the visual glow.

This may not be the end-all of innovation when compared with Sharon’s “War of the Worlds,” coming to Disney Hall in November. But nothing could be more daring than the Cleveland Orchestra next month taking this magical “Vixen” to Vienna as the first fully staged opera to be performed in the world’s most venerated concert hall, the Musikverein.

Five days earlier, the big fall project for Simon Rattle’s last season as music director of the Berlin Philharmonic will be the same Janácek opera staged in the German capital’s Philharmonie. The stage direction will be by the L.A.-based Peter Sellars, in 1992 named the L.A. Phil’s first dramaturg and someone with whom the orchestra has consistently worked ever since.

MORE ARTS NEWS AND REVIEWS:

L.A. Phil’s Mozart gala with Dudamel, Wang and flying chocolate balls

The incomparable political art of Faustin Linyekula

Yo-Yo Ma does the impossible at the Hollywood Bowl

‘Radical Women’ is a startling show you need to see, maybe twice

After 27 years in a warehouse, a once-censored mural rises in Union Station

You always can find our latest at latimes.com/arts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.