Review: ‘Painted in Mexico’: LACMA’s remarkable and important new show

- Share via

To get an idea of just how bold and ambitious painters were in 18th century Mexico, an era of unprecedented splendor in the colony of New Spain, look no further than the very first painting at the entrance to a smashing new exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

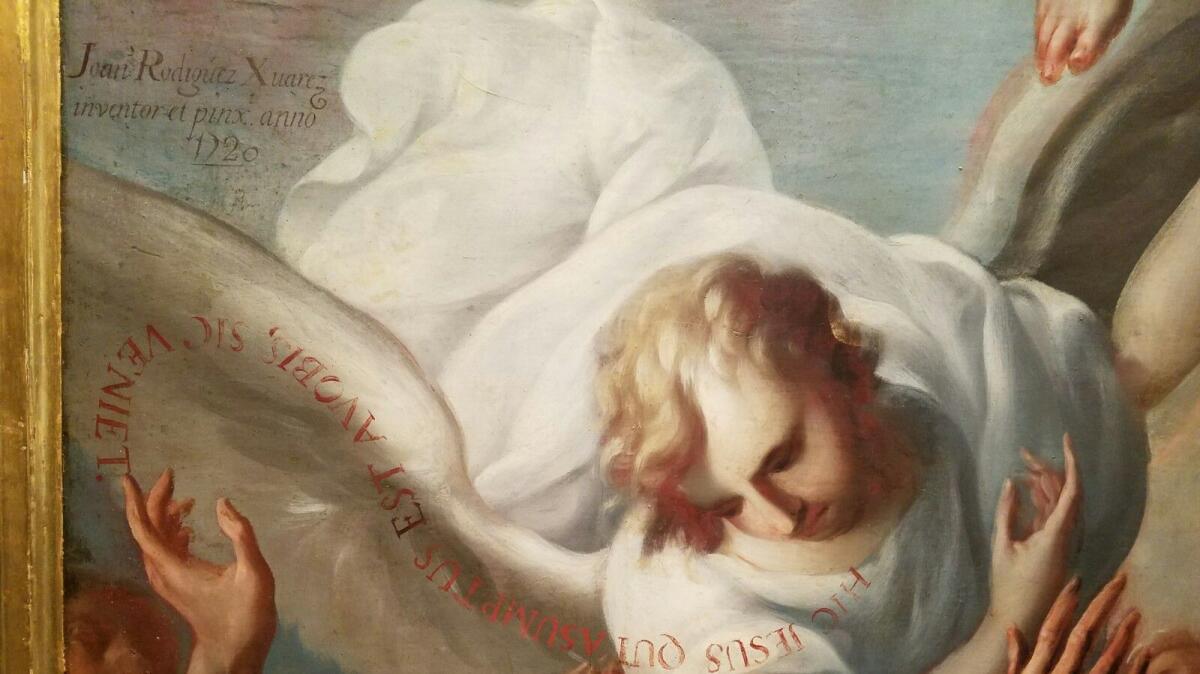

Juan Rodríguez Juárez and his brother, Nicolás, were leading artists in Mexico City early in the century. Juan’s monumental “Ascension of Christ” (1720), a painting on wood panel nearly 10 feet tall, is dominated by a life-size figure in windswept blue and crimson robes, seen from below as he levitates into the misty, cherub-filled heavens. It was one of four commissions for the chapel altar of an important Jesuit residence.

The Virgin Mary and the apostles are shown clamoring at the bottom of the scene, down where a mortal viewer of the miraculous event would also stand. St. Peter is there, imploring a golden-haired angel dramatically dressed in billowing white.

The angel is key: Responding to Peter, he gestures upward toward the ascending Christ, whose right foot is standing on the angel’s muscular left wing.

Don’t fret, the messenger seems to caution Peter; all is well. He is lofting the risen savior skyward on his wing.

An angel, of course, has two of those handy appendages. Along the top edge of the equally powerful right wing, the artist has chosen to affix his signature in elegant script. “Joannes Rodrig. Xuarez inventor et pinx. Anno 1720,” it says — invented and painted by Juan Rodríguez Juárez in the year 1720.

“Invented” may be the understatement of the year. The juxtaposition of signature and angel’s wing, paired with the central Christian miracle of Jesus riding the other wing, is an extraordinary act of supreme, dare I say “divine,” artistic self-confidence. The painter metaphorically lofts himself and his art into the celestial stratosphere, following the wondrous example of his savior.

The LACMA exhibition, “Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici,” is filled with eye-popping pictorial moments like this.

The body of a martyr floats in a river, buoyed by radiant bursts of flame at the extremities, holding him up like fluorescent jellyfish. A crumpled and flagellated Christ, his lacerated back exposing bloody ribs, stares straight out to meet a viewer’s appalled gaze, even as a cherub fluttering above him covers his eyes in squeamish horror.

A serene line of black-clad priests adores a snowy white lamb, asleep on a hovering, gilt-edged crimson Bible, its hoof tucked in between pages. Making a visual gash or wound, not unlike the one in the crucified Christ’s side, it’s no doubt a beastly bookmark for the Gospel of John 1:29: "Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world."

In several works, the conceptual layering typical of 18th century painting in New Spain gets dizzying. “Virgin of Sorrows” by Nicolás Enríquez and “Christ of Ixmiquilpan” by José de Ibarra slowly reveal themselves to be carefully wrought, highly specific depictions not of people but of life-size statues standing on altars.

Unlike the gray statues painted on the wings of many European altarpieces in deft imitation of carved stone, these are in living color. Mary’s red-velvet dress is pierced by a jagged sword thrust into her heart, while Jesus’ butterfly-style loin cloth is magnificently embroidered with gold thread. Sculptures dressed in actual clothing, these effigies of mother and son are statues that were themselves believed to have performed miracles.

Heaping piety atop zeal, the painters made devotional images of devotional objects. Their figures are life size, but Enríquez and Ibarra have given us monumental still-life paintings.

Speaking of remarkable inventiveness, the exhibition is exciting because we are literally witnessing the invention of an entire art history.

There has never been a comprehensive show of 18th century New Spanish art. The era begins in 1700 with the death of Spain’s Charles II — also known as Carlos El Hechizado, or Charles the Mad — and the transfer of power from Habsburg to Bourbon rule. The show, a herculean effort that took six years to pull off, is a first.

It was organized by LACMA curator Ilona Katzew and three co-curators: Jaime Cuadriello and Paula Mues Orts in Mexico City and Luisa Elena Alcalá in Madrid. More than 100 paintings are at LACMA, ranging from small oils on copper medallions worn as nuns’ habit décor to a monumental oval altarpiece 13 feet tall and 10 feet wide.

More than half of them needed extensive conservation work to be suitable for travel and display. (The altarpiece had been rolled up and hidden away for decades.) Fortunately, the curators had the help of a Mexican bank.

Banamex, whose exhibition space in downtown Mexico City is where the show had its debut over the summer, was LACMA’s co-organizer. In the spring, the show travels to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, thanks to the foresight of former Met Director Tom Campbell. Among the most important presentations in the ongoing Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, it is a shining example of why the Getty-sponsored program is so critical.

Many of these works have never been seen outside the churches and other religious settings for which the majority were made, others are in collections and many have never been published. The catalog is a brick — 512 profusely illustrated pages with often superlatives texts — a book destined to become a standard reference.

Exceptional talents like Miguel Cabrera and José de Páez are not unknown, but neither are they known well. Even basic biography is scant — arguments still rage over the year of Cabrera’s birth and his ethnicity — while the social and cultural contexts within which they and their often-extensive workshops practiced their art are complex.

The art of New Spain was toppled by the War of Independence, starting in 1810, then sent into oblivion by the 1910 Revolution. And not without reason: Revering the art of the Spanish Viceroyalty was beyond the pale in the immediate aftermath of an epoch when brutality reached epic proportions.

A crossroads between Europe and Asia, Mexico was the economic driver of North America courtesy of international trade. The export of tobacco from Mexico’s fields and gold and silver from its mines merged with fortuitous geography, which funneled imported Chinese and Indian goods to the courts of Europe.

For decades, “real” Mexican art has been either pre-Columbian or Modern — Aztec and Mayan or Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. That “other stuff” made during the centuries in between languished — unstudied, unloved, romanticized as provincial derivatives of European art, venerated for its religious but not artistic significance and, in many cases, hidden away or even sold for export so it would not be destroyed.

“Painted in Mexico” is an important marker in the ongoing transformation of that status. It’s a deeply absorbing show — partly because the art’s formal qualities are strangely contemporary.

As an artist friend put it, the space in New Spanish painting often seems more digital than analog.

All Baroque art is theatrical, but in Europe, the pageant takes place on an airy, unfolding stage. Take Peter Paul Rubens’ “The Elevation of the Cross,” a seamless spectacle of supremely heroic figures straining under the crushing physical weight of a body nailed to timber in a tour de force of illusionistic foreshortening.

A century later in Mexico, Antonio de Torres’ version is only superficially similar. The diagonal heave-ho of cross-raising remains central, but he pushes the action to a foreground plane, where it skims lightly across the surface of the canvas. Background figures seem to occupy the same shallow plane. Airiness gives way to cloistered order.

Who was there on Golgotha, what was happening, which figures are important, which are ancillary — the Torres painting is less a replication of what the artist’s eye could see than a record built around what his mind knows. Think of it as Colonial Conceptualism — an idea-art, albeit with closed religious and political answers to life’s mysteries, rather than expansive, open-ended questions.

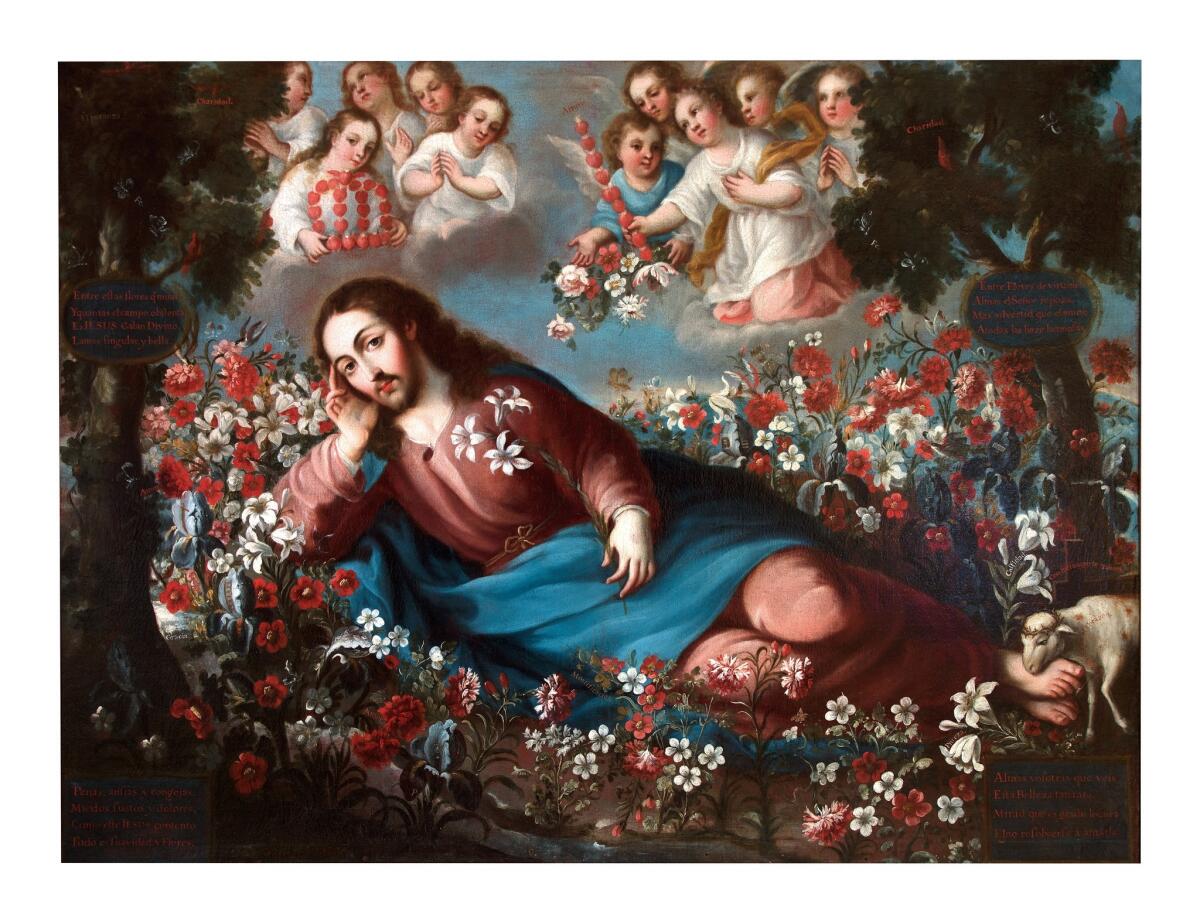

For painting, one result is the emphatic decoration of a surface.

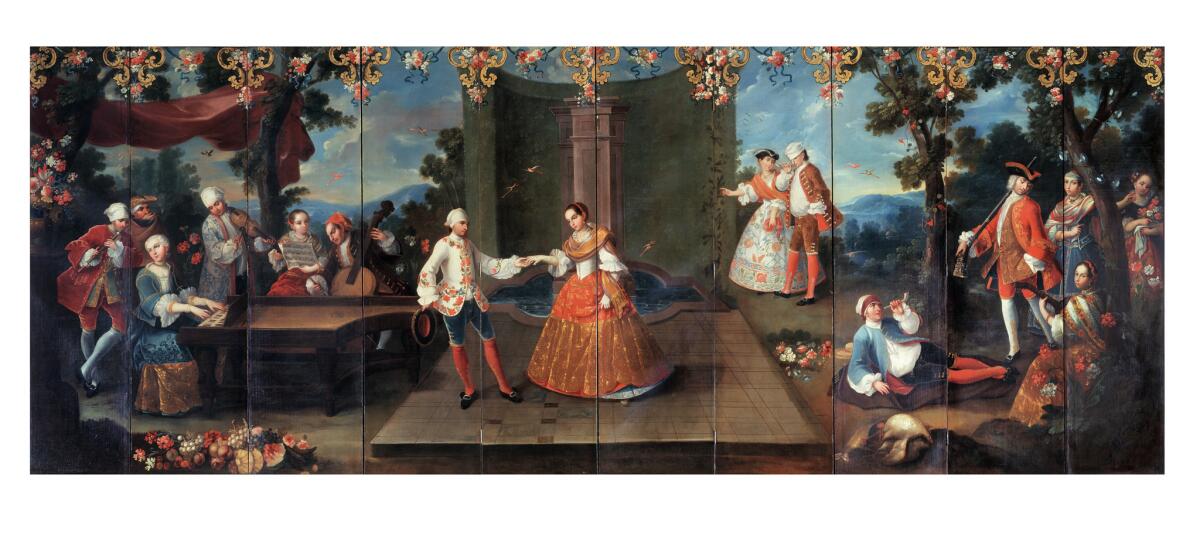

Jesus is a languid odalisque sprawling in a lush field of flowers. A 10-panel screen, meant for a bedroom, unfolds amorous flirtations in a garden. God is shown as an artist wielding a brush to paint the miraculous Virgin of Guadalupe on Juan Diego’s cloak, his palette spotted with roses instead of paint.

Mexican Baroque art depends on the imaginative elaboration of surface rather than of space — even to the extent that writing text on a picture became a common preoccupation. A huge, 10-foot-wide “Allegory of Faith” attributed to Páez is an expanse of pictorial compartments and ascetic symbols surrounded by voluminous text: Nearly one-quarter of the surface — maybe 35 square feet of canvas — is cursive writing that venerates a Carmelite friar’s journey to the Holy Land.

Art and text have been around for a very long time. But not until Allen Ruppersberg transcribed Oscar Wilde’s novel “The Portrait of Dorian Gray” onto 20 raw canvases in 1974 had I seen so much text in a painting.

The elaboration of space in European Baroque painting makes sense for a culture busily pushing out into physical space to colonize the globe. As one of those colonies, however, New Spain had no such agenda. Like any bureaucracy, it was instead inventing flowcharts, managing complex information and consolidating clout.

Surface elaboration revs up into flabbergasting overdrive in portraiture. Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz conjures an astonishing array of sumptuous textures — rich velvet, delicate lace, rouged skin, brittle glass or tile, sumptuous brocade, powdered hair, glinting gems and glowing pearls — into an exquisite portrait of a young aristocrat about to take her vows as a nun. Such elegant, sundry decoration sanctifies her social station, while signaling all the worldly splendor she is about to give up as she heads into the asceticism of convent life.

Morlete Ruiz is one of seven artists — together with the Rodríguez Juárez brothers, Ibarra, Cabrera, Páez and Manuel de Arellano — who stand out among the show’s two dozen painters. Yet, they all provide worthy and essential context for an extraordinary artistic era just coming into focus. “Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici” is a remarkable curatorial achievement, one of the most memorable exhibitions of the year.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

“Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici”

Where: LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Through March 18; closed Wednesdays

Info: (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE ARTS:

Applause, and a caution, for Museum and Institute of California Art

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.