From the Archives: Music, TV, Fireworks; Maestro Previn Takes Over

- Share via

It certainly wasn’t just another opening, another show. To celebrate the arrival of Andre Previn as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic on Thursday night, our cultural guardians pulled out a few extra extramusical stops.

Before the concert could begin--at the new, welcome, civilized hour of 8--there had to be celebrating on the plaza outside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Lights. TV cameras. Free “Previn & The Los Angeles Philharmonic” buttons, with a heart in the middle. Serenades by the Moravian Trombone Choir of Downey.

After the concert, before the climactic cadences of the formal program could even begin to evaporate, the Moravians returned to their alfresco tootling, and the party resumed. Lights. TV cameras. Free wine and mineral water. Eventually, fireworks!

FULL COVERAGE: Inside the L.A. Philharmonic

Inside the hall it wasn’t exactly business as usual, either. The stage apron resembled a veritable jungle of floral tributes. The ubiquitous cameramen stalked the aisles, distracting attention from the music-making in their dauntless quest to preserve every moment of this momentous occasion for a televisionary posterity.

And so the Previn era began.

Predictions at this juncture may be premature, to say the least. Still, it seems reasonable to suggest that Previn won’t specialize in brawny flash, as Zubin Mehta did. Nor will he luxuriate in mellow, old-world poetry, as was Carlo Maria Giulini’s wont.

Despite the brouhaha surrounding his official debut and despite the glitter of the Hollywood background that no one here except the maestro wants to forget, Previn appears to be serious, thoughtful, tough and bold. The Philharmonic may--just may--be entering its no-nonsense phase.

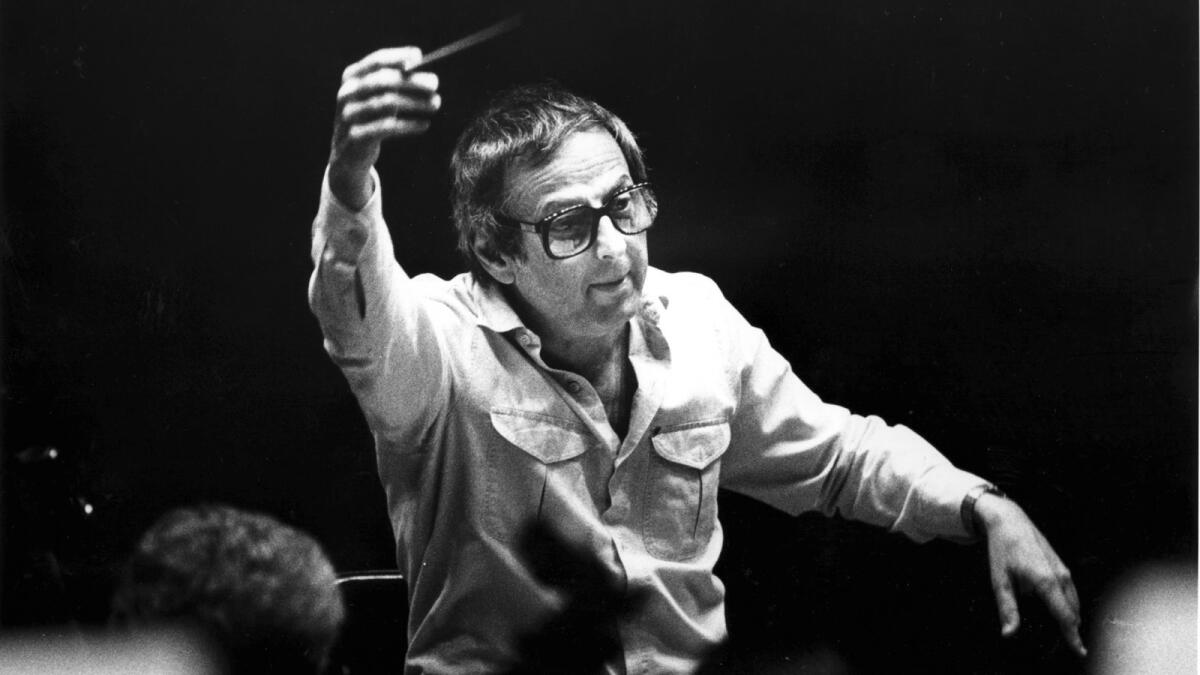

Small, slender and bespectacled, Previn does not create the most romantic of images on the podium. Moreover, he favors economic gestures over flamboyant exhortations. He doesn’t shrink from the ungainly motion if it seems useful. Without much fuss or furor, he concentrates on such old-fashioned virtues as clarity, precision and momentum.

In this day of matinee-idol indulgences, he seems content to conduct the orchestra, not the audience.

Although he may not be a wild avant-gardist, he doesn’t go out of his way to court the masses. He opened his debut program with a rather noisy West Coast premiere, continued with some sophisticated classicism and, for a grand finale, explored a great Russian symphony.

The dressy first-nighters in the sold-out house would, no doubt, have wanted Tchaikovsky--some push-button weeping and wailing and sighing, some hum-along hit tunes, some comfortable orgasmic crashes. Previn gave them Prokofiev.

The crowd did, of course, muster a standing ovation at the end. It was a proper, respectful, de rigueur standing ovation. It did not reflect a blitz of spontaneous communal frenzy. There will be time for that, perhaps, later.

After the obligatory ritual of the “Star-Spangled Banner” (which, as usual, prompted at least one wag out front to utter a not-so-sotto voce “Play Ball!”), Previn introduced the “Celebration for Orchestra” of Ellen Taafe Zwilich. A snappy little piece d’occasion , it was written by the winner of the 1983 Pulitzer Prize to help the Indianapolis Orchestra inaugurate the Circle Theatre last year. It represents a nice, gutsy cluster of fanfares, a carefully gauged, easy-to-take acoustical experiment that rings various orchestral bells with facile affect.

It doesn’t pretend to probe musical depths. Nor does it try to stretch attendant ears. But it does raise a seasonal, even epochal, curtain with a decent flourish.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 39, K. 543, turned out to be a bit more problematic. The Los Angeles Philharmonic has never responded very sensitively to the need for elegance and introspection that such repertory implies, and Previn is not the sort of conductor who values subtlety and finesse above all else. Under the circumstances, one had to be grateful for limited favors: accuracy, poise, dynamic restraint and robust spirits. Charm, cantabile expansion and gentle warmth may remain elusive, but no orchestra has ever become a Mozart orchestra overnight.

Previn came emphatically into his own with the Prokofiev Fifth Symphony. He surveyed the sprawling passions and the abiding grotesquerie with a cool, obviously appreciative eye. He allowed no excesses, resisted vulgarity and bombast, sustained a fine sense of proportion and projected an uplifting sense of drama.

This was intrinsically tasteful Prokofiev, Prokofiev propelled with impeccable rhythmic definition, Prokofiev enlivened with bold splashes of orchestral color and telling expressive nuance. Crucially, it was Prokofiev that savored arching lyricism as well as primitive thunder.

The Philharmonic, which has not always been the most tidy of orchestras in recent years, gave its new boss the taut line, lean textures and technical brilliance he obviously favors. This was Previn’s night, and the orchestra played for him like an ensemble of sympathetic virtuosos.

BACK TO THE SERIES: Inside the L.A. Phil

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.