Review: ‘Made in L.A. 2016’: Hammer Museum biennial proves a thoughtful place to ponder the possibilities

- Share via

Where is Todd Gray?

The artist is one of 26 included in the latest installment of the Hammer Biennial, “Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only.” The diverse survey of recent art opened last week at the Westwood museum, but Gray’s work is nowhere to be seen.

That absence is by design.

FOR THE RECORD

June 27, 1:14 p.m.: This review says that artist Daniel R. Small excavated items from the movie set for Cecil B. DeMille's "The Ten Commandments" and incorporated them into an installation. The excavated items in his "Excavation II" are on loan from the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Center and private collections. The artist did not participate in their excavation.

Gray, a well-known commercial photographer in the music industry as well as an artist whose work is included in numerous museum collections, is restaging an extended performance piece suggestively located at today’s perplexing crossroads of art culture and celebrity culture. Its title is “Ray.”

Most popular articles in entertainment this hour »

For a full year following the 2013 death of his friend Ray Manzarek, keyboardist for the classic rock band the Doors, Gray wore only clothing that had belonged to the musician. In the Hammer’s lobby, an unobtrusive wall label says that he is doing it again for the duration of the museum show.

Should you bump into the artist as he goes about his daily life between now and the show’s Aug. 28 closing, you will certainly experience his work. The clothing is a public “second skin” — an outward sign of an inward life, which is a pretty good description of most works of art.

You might not even know it, though, depending on whether you recognize Gray and are aware that a performance is underway.

Even if you don’t encounter the artist, however, simply knowing about the performance means you are aware that he is out and about somewhere in the world doing something. Going to the grocery store. Meeting friends for dinner. Hiking in the hills.

One can only wonder: Will you have a sighting of this elusive figure? That’s a pretty good characterization of celebrity, where the intersection of public and private life is a contested blur.

The title of Gray’s performance also makes a wry nod in the direction of Charles Ray, the celebrated L.A. sculptor who made his own ordinary wardrobe a centerpiece in works like “All My Clothes” (1973), a series of documentary Polaroid photographs of exactly that, and “Self-Portrait” (1990), a conventional department store mannequin dressed like him. Their echo in the Hammer show neatly ties art and celebrity together.

Hammer biennials focus exclusively on art made in the L.A. region and have “an emphasis on emerging and under-recognized artists,” to quote the press materials. Gray’s italicized performance ponders whether a tree falling in the forest makes a sound, if no one is there to hear it. He has lodged his tongue firmly in cheek with a sly performance in which “under-recognized artist” takes on literal meaning.

The 2016 biennial was organized by Hammer curator Aram Moshayedi and guest curator Hamza Walker of Chicago’s Renaissance Society museum. (It’s the first time in three biennial outings that a curator from outside L.A. has been invited to participate.) Their hefty, thoughtful catalog lays out a variety of considerations undertaken in their selection of artists.

It begins with the city’s distinguishing feature as image capital of the world, which has an effect on art made globally. (See — or don’t see — Gray, former personal photographer for Michael Jackson.) Its 26 artists are fewer than in earlier biennials — 35 last time and 60 in 2012 — and a third are foreign-born.

For me, two themes dominate the show. One is the tension between the virtual world of the Internet (and its lens-based ancestors of photography, film and TV) and the actual, physical stuff of art. The other is the museum itself as an organized archive of objects.

Such a show’s image-object godfather might be German painter Gerhard Richter, whose work alternates between fuzzy photographic realism and blurry, squeegeed abstractions. For good measure, Richter has also been compiling an enormous “Atlas” of photographs, newspaper cuttings and sketches from the last 50 image-saturated years.

Several archival displays turn up, including vitrines holding artifacts fabricated in an Art Deco style nearly a century ago for the Egypt of Cecil B. DeMille’s epic silent-movie “The Ten Commandments.” Artist Daniel R. Small excavated them from the set’s burial site near Santa Barbara, and he shows them here with a backdrop of paintings commissioned for and later sold off by the Luxor hotel in Las Vegas.

The installation is loosely reminiscent of "Re-Claiming Egypt," New York Conceptual artist Fred Wilson’s compelling contribution to the 1993 Whitney Biennial. DeMille’s silent movie is about biblical Exodus — Greek for “the way out” — and Vegas is one contemporary definition of escape. Small’s seriocomic analysis of culture high and low is engagingly designed to set you free.

Excavation of a different sort drives Rafa Esparza, whose big field of adobe bricks is made from the dirt of Chavez Ravine, a once-thriving Latino barrio notoriously bulldozed to make way for Dodger Stadium. Esparza digs up history, including a traditional building technique plus junk unearthed at the site, for a Minimalist floor sculpture meant to be walked on. Sculpture is transformed into a pedestal for people.

Gala Porras-Kim borrowed a slew of unidentified artifacts from the storeroom of UCLA’s Fowler Museum and presents them on a plinth mostly unadorned. Museums typically tell us what an object is, but this display shrugs its shoulders.

Several are subjects for Porras-Kim’s acute graphite drawings, where the abstract quality of mystery objects — Is that a hat? A basket? — is further heightened. Your mind begins to assign functions and meanings, even as plain visual pleasure rules.

In a clever move, the curators have chosen four artists — three septuagenarians and an octogenarian — for mini-retrospectives. This classic museum function is tucked inside the survey show. (The smaller number of biennial artists helped make it possible.) They’re a bright spot.

Huguette Caland works in just about every medium — about 50 paintings, drawings, sculptures and textiles are here — but her oddball fusion of figurative and abstract imagery sexily rendered in intense color is most surprising. In “Bribes de corps” — body scraps — two billowy vertical forms in a ripe peach hue flaming against turquoise blue slowly reveal themselves to be thighs and knees.

Presumably they belong to the seated artist. She looked down and then up to the linen canvas and back again to paint her sensuous self-portrait.

Thirty-five carved, polished, assembled, adorned and otherwise fabricated upright totems by Kenzi Shiokava coax a keen intensity from mundane material substances — wood, glass, bamboo, cord, etc. The human-scaled towers, more compelling than his nearby boxed assemblages, recall precedents as diverse as Louise Bourgeois, Isamu Noguchi and Peter Krasnow, but with a personality all their own.

The jazz scores of Wadada Leo Smith, surveyed from the 1960s to now, function as visual cues for how a free-form musician is to proceed, not about what to play. The stacked rainbow hues of “Pacifica,” for instance, suggest the sport of a sailboat skipping across waves. You can’t hear the music, but you can feel what he’s after.

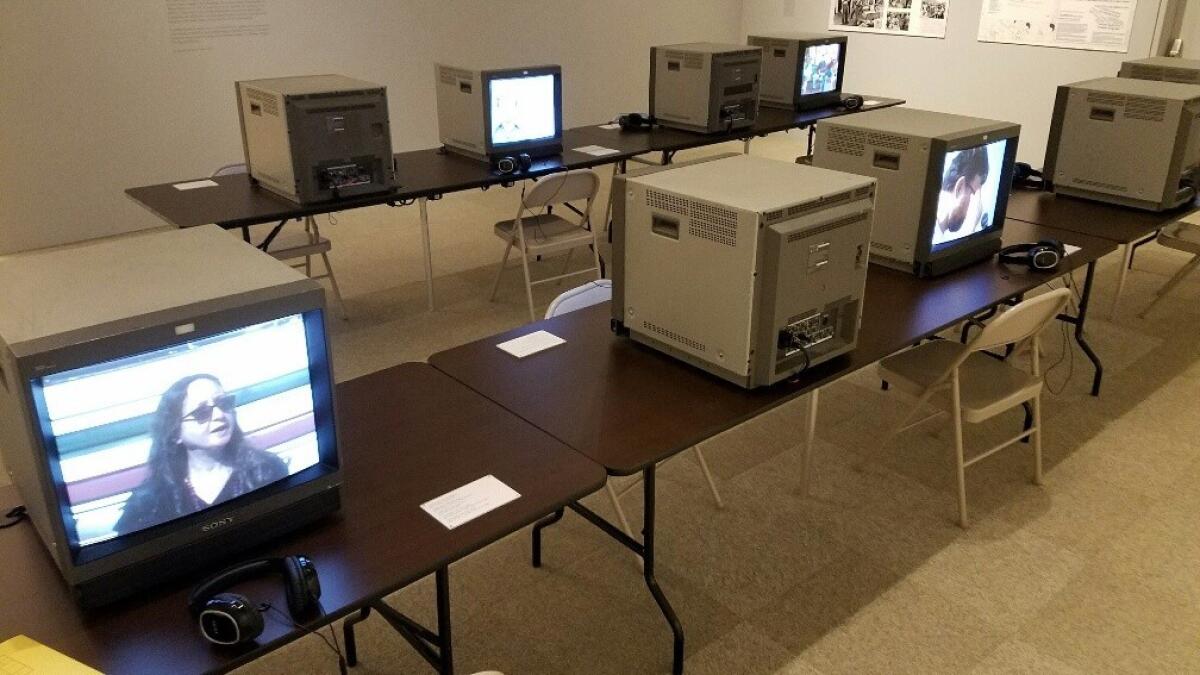

Finally, more than 20 years of Labor Link TV, a public-access television show established by a group of San Diego union activists and artist Fred Lonidier, play on 10 video monitors atop work tables outfitted with folding chairs. Media outlets today have business sections, not labor sections, and public access is home to the shrinking labor movement archived here in speeches, meetings and protests. This is the show’s Bernie Sanders gallery.

Two beguiling films parse the friction between the virtual and the physical from different angles.

Margaret Honda’s film “Color Correction” is a unique object, presented in the gallery inside the frame of its metal canister. The film is 101 minutes of monochrome color sequences, all taken from a technical process in which an unidentified commercial movie was readied for release.

The experience of seeing projected light in a theater is one thing (the abstract film is screened during the show’s run), but seeing a real canister on a pedestal is also weirdly affecting. It’s like a burdensome industrial time bomb waiting to go off.

Honda takes a structural approach to the irreducible physical facts of film. Its ancestry leads to 1960s films by Canadian artist Michael Snow. His famous 45-minute zoom, “Wavelength,” likewise bubbles up when watching Laida Lertxundi’s mind-bending film, in which a stabilized camera moves seamlessly backward through L.A. alleyways. The vanishing point of the city’s sunny backstage landscape continuously recedes from view, like an evaporating dream.

“Made in L.A. 2016” exhibits a familiar, enduring L.A. aesthetic trait — a relaxed, even casual quality that is especially refreshing in the frenzied here and now of our market-dominated art world. It pries open a focused space for thought, a space that even gets an intermittent soundtrack through speakers hidden here and there to play musical fragments by Guthrie Lonergan.

The artist gives us elevator music marvelously reimagined. If not everything in the show rewards attention, enough does to merit spending some time.

-----------

“Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only,” UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood. Through Aug. 28. Closed Mondays. (310) 443-7000, www.hammer.ucla.edu

Twitter @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.