Review: Grafton Tyler Brownâs California scenes at Pasadena museumâs final show

In 1879, Grafton Tyler Brown took a giant leap. A successful San Francisco businessman, then 38, he decided to become a Western scene painter. Brown sold his thriving lithography company and headed out to see the sights, brush in hand.

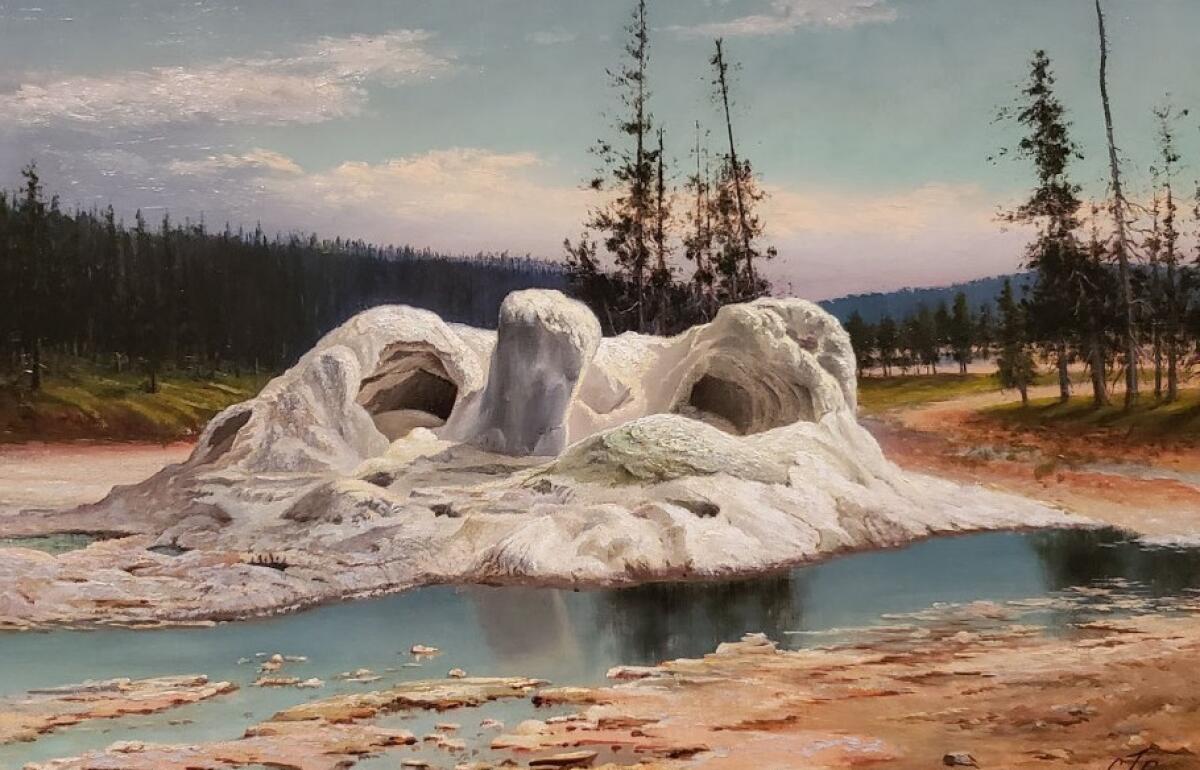

Over the course of the next dozen years, he produced picturesque portraits of Mt. Shasta and Mt. Rainier, the Cascade Gorge along the Columbia River and the geysers of the newly anointed National Park at Yellowstone. A sliver of what he saw on those wide-ranging travels is now on view in âGrafton Tyler Brown: Exploring California,â a modest exhibition at the Pasadena Museum of California Art.

Two other Brown exhibitions have been done â the first at the Oakland Museum in 1972, which focused on his commercial lithographs, and a 2003 survey of 49 paintings at the California African American Museum. (The painting show traveled to Baltimoreâs Walters Art Museum.) One wishes that the Pasadena show had managed a full overview of his entire output, lithographs and paintings alike. Thatâs long overdue.

Unfortunately, neither is there a catalog about the self-taught artistâs fascinating history. Tight funds, I suppose.

The Pasadena museum confirmed recently that it will close its doors when the Brown exhibition, along with two more shows, ends Oct. 7. (The others are a display of Judy Chicagoâs âBirth Project,â mixed-media works from 1980-85; and a sculptural installation, âStrata,â by Brody Albert.) Thatâs a pity, though not surprising.

In fact, whatâs surprising is that the museum lasted so long (16 years). The PMCA, which does not have a permanent collection, was launched in 2002 by Robert and Arlene Oltman, wealthy collectors of California art, using a bizarre and, finally, unsustainable financial plan.

The couple reportedly underwrote the $5 million construction cost of the building, which included a penthouse apartment where they live; they planned to finance operations for just five years. The hope seems to have been that institutional success would bring forth additional funding sources.

It seems it didnât, except in relatively minimal ways. (There is no museum endowment.) A review of tax filings shows a tangled process of financial support in which the Oltmans made tax-deductible, seven-figure contributions to fund operations, while simultaneously receiving six-figure rental income for the use of their building as exhibition and office space.

Institutional stability is not reliably built on what is essentially a single primary funding source, even if the fiscal roundelay makes the dollar go a bit further. Both husband and wife were simultaneously serving as museum trustees, and staff turnover has been steady. The loopy structure is not one that might inspire confidence in potential outside donors.

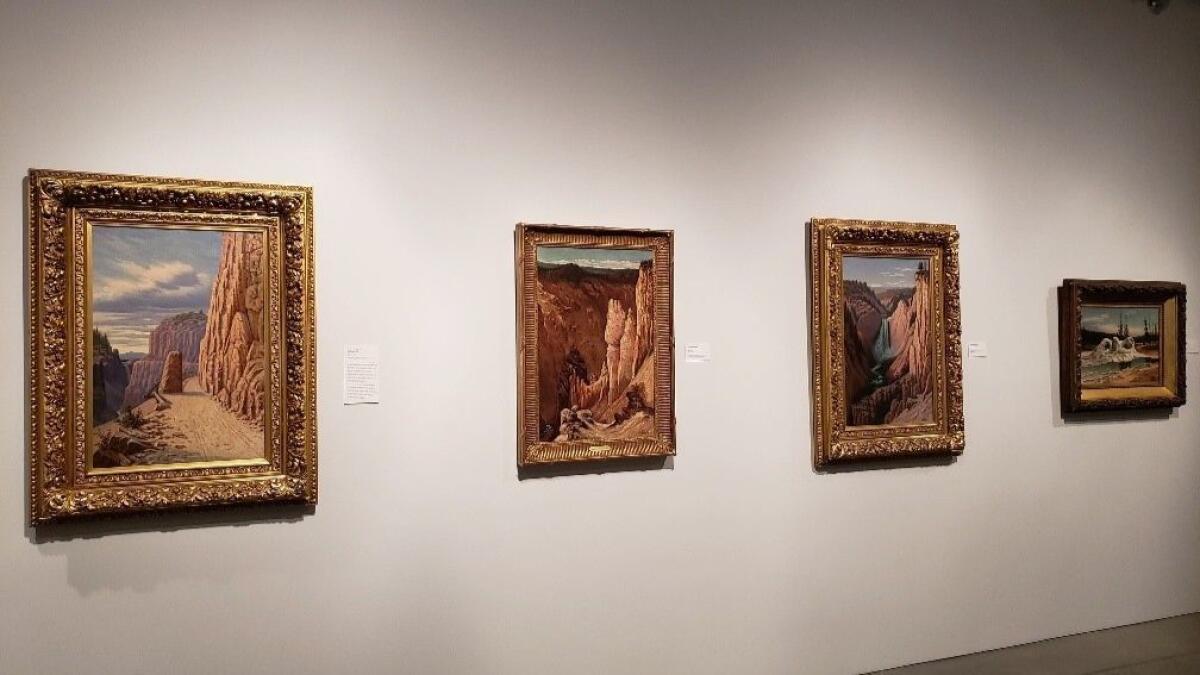

UC Irvine professor Bridget R. Cooks, guest curator for the Brown show, has assembled 11 oil paintings, 22 lithographs and some examples of commercial printing projects executed during the artistâs earlier years in the litho business. (Ornate mining stocks, elaborate office stationery for Levi Strauss and Folger coffee, a small decorated crate for a soap company and the like are displayed in cases.) Think of the ensemble as a thumbnail sketch.

The showâs subtitle, âExploring California,â fudges things a bit, since most of the selected paintings go farther afield than one state. But it is not difficult to discern the connection between his Bay Area lithographic business and the oil paintings of scenic landscapes that he made from Wyoming to British Columbia.

One quirky service Brown offered in San Francisco was making lithographic portraits â not of people but of their houses. A proud ownerâs home at Half Moon Bay or a sprawling ranch in San Mateo could be recorded for posterity, complete with the family gathered out front or perhaps riding by in a carriage.

He also made topographical pictures of entire towns, sometimes used for civic promotional purposes. The best known, although not in the show, was a 72-plate illustrated history of San Mateo County, which he completed just before he decided to sell his business.

Later, Brown translated the general motif of domicile portraits into oil paintings â witness a rather crude 1889 picture of an Oregon farm that was no doubt cherished by the resident who commissioned it. The simpler lithographic prints, less ostentatious, tend to be more charming; but, either way, making portraits of real estate somehow seems a very California thing to do.

Think of them as a kind of personalized subset of scene painting â a genre that records, revises, celebrates and promotes notable landscape views. Niagara Falls is the great 19th century example, painted by everyone from the pious Edwin Hicks to the rapturously besotted Frederic Edwin Church.

The two most compelling works in the Brown exhibition are at opposite ends of the scene-painting spectrum.

One is âCascade Cliffs, Columbia Riverâ (1885), an elaborately detailed view of a prehistoric forest that has been partly cleared to accommodate the arrival of the railroad. Tracks begin at the bottom of the picture, pulling a viewer into the scene. They curve around behind a hill, dropping off your eye at a broad river in the distant middle-ground. There, a steamboat chugs along beneath a cloudless azure sky.

The backdrop to this placid scene of idyllic human industry in the remote wilderness is an imposing mountain in the Cascade Range. Brown has rendered it as a giant triangular form. Itâs as if the massive peak is an ancient Egyptian pyramid â an American Luxor by a Western Nile.

Between two big foreground trees, an eccentric detail stands out. A dead tree limb just happens to follow â exactly, spiky twist by pointy turn â the jagged shape of the open space that separates the two treesâ foliage. Nature as a bountiful resource for commercial exploitation is the paintingâs subject, underscored by a mountain that belongs to both nature and civilization and by a tree branch artfully composed by a stylish painter.

The other absorbing picture is not much more than an oil sketch, perhaps dashed off on site around 1884 for later elaboration in the artistâs studio.

Quick, stippled brush marks conjure a leafy tree, while loose strokes of color cut a roadway through the grasses to what appears to be an Indian burial mound on the horizon. If you didnât know that âIndian Grave, Neah Bay,â was painted in Washington State, you might mistake it for a modern French Impressionist picture of farmland near Giverny.

Much more deserves to be known about Brown, the first African American artist believed to have been working in 19th century California. Light-skinned, he began to pass as white sometime after moving west from Harrisburg, Penn.

He launched G.T. Brown & Co. just as the Civil War was ending â perhaps a sign of candid optimism â and the business prospered throughout the Reconstruction era. But with patrons such as Benjamin Franklin Washington, editor of the then-openly racist San Francisco Examiner, Brown lived with the grinding daily risk of exposure. One cannot help but wonder whether the fitful end of Reconstruction in 1877, with its troubled aftermath for black Americans, might have propelled his decision to head out into the wilderness to paint scenic landscapes.

The exhibition is silent on such questions, which are of pressing topical relevance to American life today, but it is nonetheless worth seeing before it shutters in October. The lack of completeness is disappointing, but that might serve as a chastening metaphor for the museum itself.

Grafton Tyler Brown: Exploring California

Where: Pasadena Museum of California Art, 490 Union St.

When: Through Oct. 7. Closed Mon.-Tue.

Info: (626) 568-3665, www.pmcaonline.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.