Review: ‘Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album’ buoyed by photos with cinematic insight

- Share via

“I shoot a lot of crap,” Dennis Hopper once said of his photographs, most of which date from the early to mid-1960s, the period when the difficult actor, often unemployed, most avidly wielded a still camera.

Ample evidence is offered in an exhibition of unearthed pictures that apparently have not been seen in the U.S. for nearly 50 years. (Hopper died in 2010, and the work was shown in London in 2014.) Yet, it also shows why Hopper’s photographs are worth looking at.

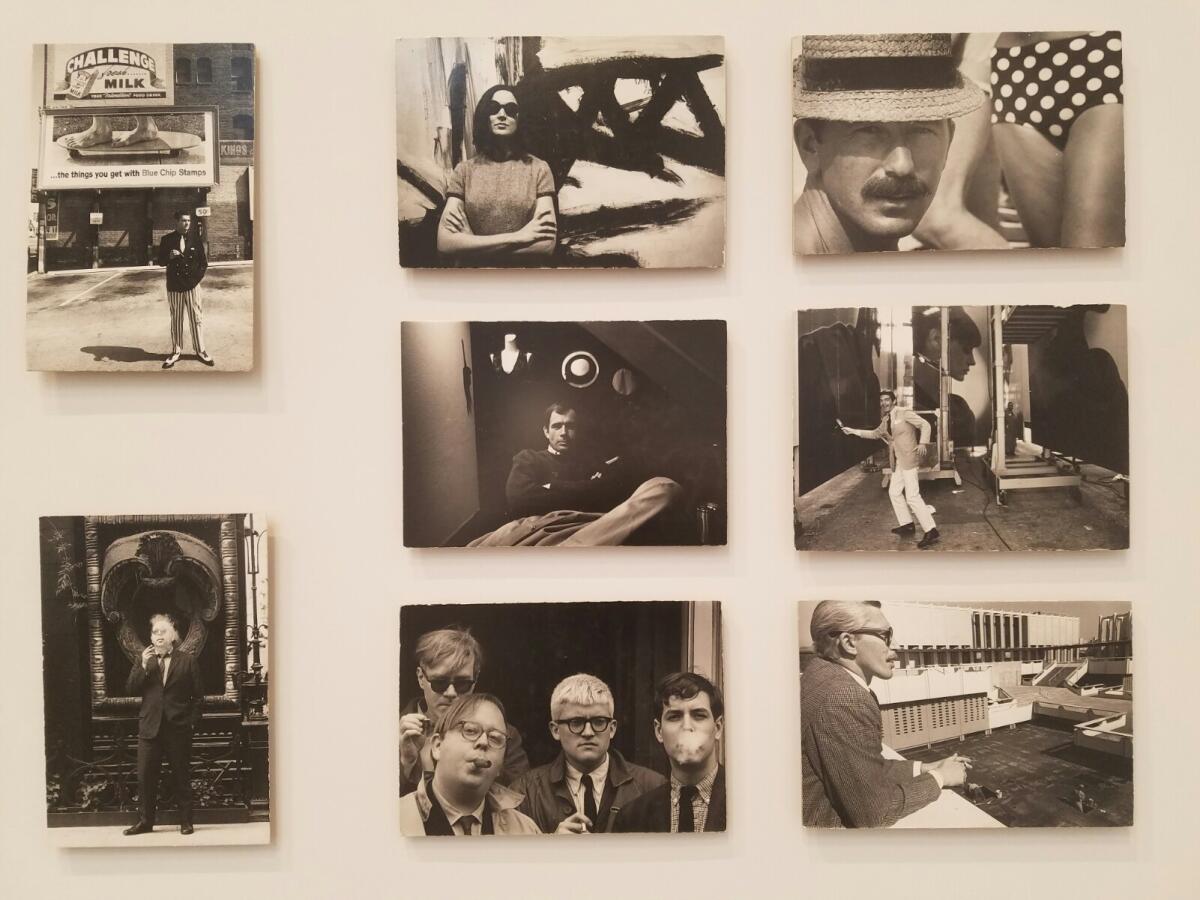

Sorting through the more than 375 images in “Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album” at Michael Kohn Gallery, mundane if sometimes useful documents of their time and place are peppered with photographs that sing.

Photographs are clustered by subject and theme — portraits of artists, biker gangs, bullfights, a homeless man with a baby carriage foraging by the side of a road, hippies and Holy Rollers. Artists typically engage Hopper’s camera most directly, unsurprisingly conscious of the power of images.

Surprises do emerge, such as the latent homoeroticism of roughhousing Hells Angels. Numerous pictures of battered and paint-peeling urban walls shout “serious” abstraction, but they’re wholly derivative of 1950s photographs by Aaron Siskind and others. Scanning the dross adds dramatic punch to the best works, which flare into consciousness as little cinematic bursts of powerful insight.

Take a group of pictures shot during the 1965 Freedom March from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery, culminating in a remarkable photograph of

King is shunted to one side, as if cornered by a mass media hungry to hear and broadcast his words — “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice” — as well as to devour him. Hopper, by then a significant Hollywood celebrity and an intimate of such pop artists as Edward Ruscha and Andy Warhol, understood the double-edged media dynamic.

In another, a man weighs himself on a big sidewalk scale, the kind that used to be common outside small-town pharmacies. A blaring advertising banner in an adjacent store window proclaims, “We give Blue Chip stamps.” The silent juxtaposition of scale and blue chip wryly identifies weightiness with quality.

Black-and-white, uncropped, printed full-frame and casually mounted on cardboard, the photographs were shown in 1970 at the Fort Worth Art Center, forerunner to today’s Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and then directed by Henry T. Hopkins, former curator at the

The work is shown in a comparable manner at Kohn. If you saw the blandly overblown 2010 Hopper retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, which featured lots of bad paintings and sculptures draped in celebrity gauze, don’t let it deter you from visiting this far more revealing show.

Michael Kohn Gallery, 1227 N. Highland Ave., Hollywood. Through Sept. 1; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 461-3311, www.kohngallery.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.