Column: The connection between Gordon Davidson and Neville Marriner, and what it means for modern-day L.A.

- Share via

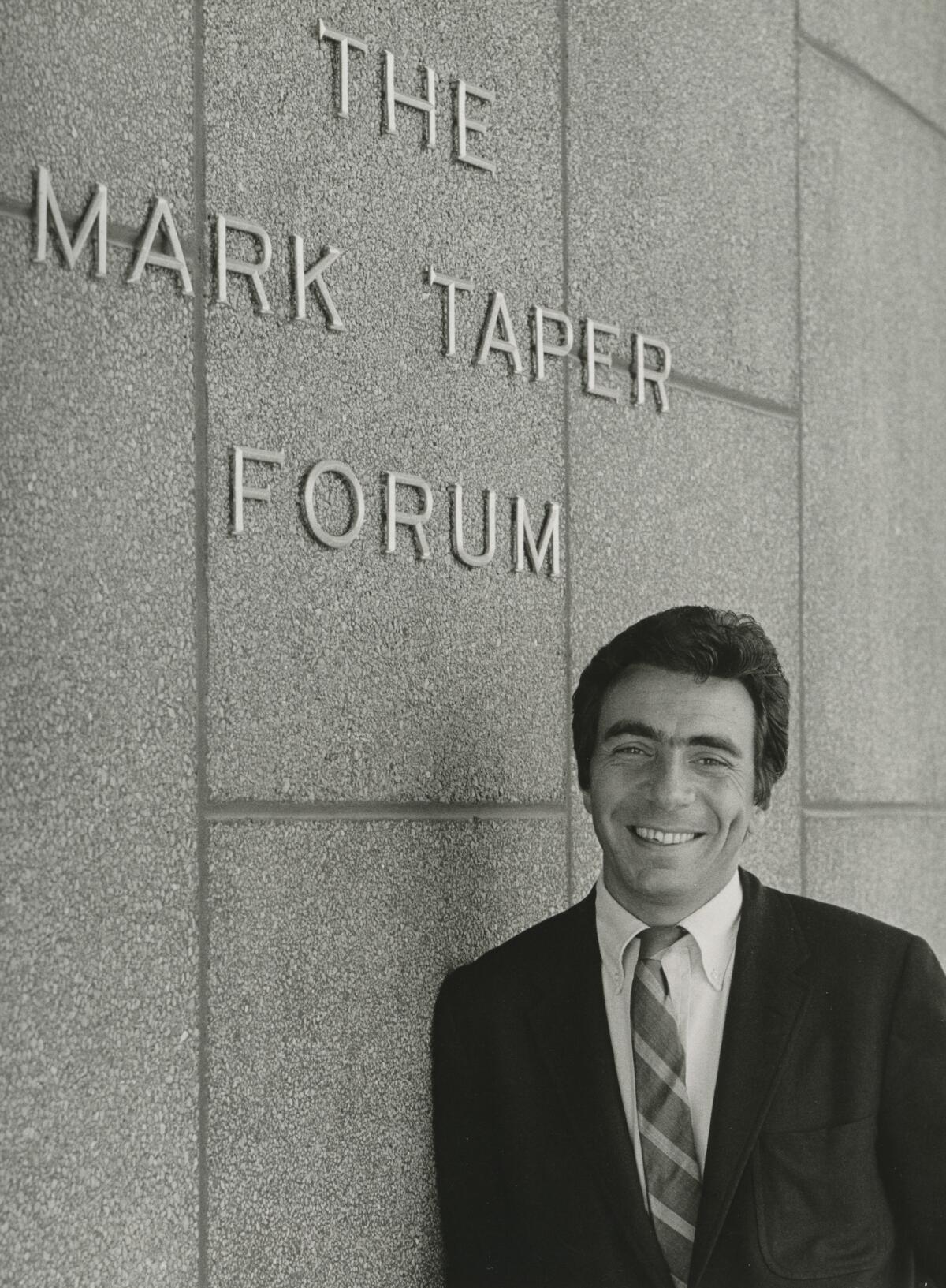

The Music Center is lowering its county flag to half-mast for Gordon Davidson, who died Sunday at age 83. As founder of Center Theatre Group at the Mark Taper Forum, he made Los Angeles a theater city.

The flag, however, can just as easily be meant for Neville Marriner. The British conductor, who also died Sunday, was the first music director of Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. The ensemble never became an official resident company of the Music Center (try though it did), but for its first decade — the period that Marriner led LACO — it played in the Mark Taper Forum.

To lose two old Music Center lions at once makes it tempting to talk about the end of an era. That’s not quite right. Davidson’s era ended when he stepped down from Center Theatre Group in 2005, whereas Marriner, who was 92, remained active to the end, conducting in Italy just days before he died.

The two men didn’t exactly collaborate. Yet both were instrumental in creating an ethos in the early era of the Music Center that’s worth revisiting as the institution, having recently entered into its second half-century, tries to become newly relevant.

We can’t, of course, talk about Davidson without starting, as all the tributes to him properly have, with his provocative opening production at the Taper in 1967 of “The Devils,” John Whiting’s play based on the Aldous Huxley novel. Neither Gov. Ronald Reagan, who stormed out, nor Cardinal James Francis McIntyre were ready for a tale of sexually possessed nuns in 17th century France.

Less attention has been given to the opening concert of the newly formed Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra two years later in the Taper. During the initial planning, the 740-seat theater-in-the-round was expected to be a venue for theater and chamber music. For the first 10 years that was the case, although musical programs had to be fit in on nights that the Center Theatre Group was dark.

The acoustics were on the dry side, but the intimacy and ambience — the musicians played on whatever theater set happened to be up — were ample compensation. A double bill of experimental new plays about altered consciousness and the sexual mores of the 1960s, (Joel Schwartz’s “Tilt” and Israel Horovitz’s “Line,” the latter directed by Davidson and staring Richard Dreyfuss), opened shortly before the LACO’s Taper debut on Oct. 29, 1969. So there had to be a certain frisson for that black-tie, first-night crowd encountering Bach, Vivaldi and Handel against a semi-psychedelic backdrop.

The setting, moreover, played right into Marriner’s idea for the new orchestra. The conductor had begun to make his name as a populist Baroque specialist at the time of the first big revival of Baroque music. He didn’t go in for the historical approaches being experimented by academics at the time, but Marriner did believe that early music needed to be lively and immediate. A decade earlier Marriner had founded the English chamber orchestra Academy of St. Martin in the Fields and already was on his way to becoming the second-most recorded conductor (after Herbert von Karajan) in history. He shared with Davidson the unpretentious ability to make what might seem unapproachable feel mainstream.

Best of all, Davidson’s Taper brought out an unexpectedly adventurous side in Marriner. After the success of his first LACO concert, Marriner told The Times that he wanted to devote his new orchestra to Baroque and the avant-garde of Boulez, Berio and Stockhausen. Neither his L.A. audience nor Marriner himself was quite ready for that. But Marriner did pepper the Baroque with all kinds of wonderful things, including Charles Ives and Virgil Thomson.

In the end, theater won out. Davidson simply made Center Theatre Group too essential, and although LACO loved the intimacy of the Taper, a 740-seat theater wasn’t financially viable. The Taper was renovated, making it less viable for music. After 10 years, a much-loved Marriner moved on and so did a newly assured LACO, first to the Wilshire Ebell, then to the Ambassador Auditorium in Pasadena and now the Alex Theatre in Glendale and UCLA’s Royce Hall.

In the meantime, as the Music Center matured institutionally, it also became more territorial. The Los Angeles Philharmonic bristled when it had to share what it considered its Dorothy Chandler Pavilion with the Joffrey Ballet and Los Angeles Opera, finally building its own Walt Disney Concert Hall.

There remained a modicum of collegiality. From time to time, the L.A. Phil played in the pit for opera. Davidson was invited by the L.A. Phil to direct a memorable production of “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour,” a striking collaboration between then-L.A. Phil music director André Previn and playwright Tom Stoppard.

Companies do continue to collaborate these days, especially the Los Angeles Master Chorale and L.A. Phil. The chorus’ music director, Grant Gershon, will conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic in John Adams’ “El Niño” in December, and Gershon is also resident conductor of Los Angeles Opera.

But lines are clearly drawn. Music stays in Disney Hall. Saturday afternoon as I was wandering around during the L.A. Phil’s “Noon to Midnight” new-music marathon all over the hall, I marveled at how Frank Gehry angled the line of his new building’s roof to reflect that of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. It makes you want to cross 1st Street, which I would like to see closed off and the Music Center made one, as it once was able to be when it was smaller and a sense of discovery was in the air.

In retrospect, and a little eerily, something of the spirit of Davidson and Marriner was apparent on their last full day on Earth, as young musicians, full of imaginative gumption, came to Disney Hall on Saturday for the festival. Now let’s turn to our two lost lions as inspiration to make that pervasive.

Neville Marriner, L.A. Chamber Orchestra music director and 'Amadeus' maestro, dies at 92

Gordon Davidson, Mark Taper Forum founder and L.A.'s 'Moses of theater,' dies at 83

Critic’s Appreciation: Gordon Davidson changed L.A.'s image of itself

The L.A. Phil's nonstop new music marathon, 'Noon to Midnight'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.