Review: Turning rhyme for the ears into rhythm for the eyes: It’s ‘Concrete Poetry’ at the Getty

- Share via

What's on view in a terrifically lively show at the Getty Research Institute has gone by various names — concrete poetry is the most common, but also visual poetry, spatial poetry and imaged words, among others.

A wholly satisfactory term for it may remain elusive, but the material itself is the opposite: immediate and accessible. It reaches us through multiple points of entry, stimulating several senses at once. For those intimidated by, or reflexively resistant to, more traditional forms of poetry, concrete poetry could be what breaks down that barrier.

"Concrete Poetry: Words and Sounds in Graphic Space" traces an international movement from its beginnings in the early 1950s through the '70s. Poets in Brazil, Austria, Scotland, France, the U.S. and elsewhere staged a revolution against syntax and the poem's conventional delivery system, a column of lines meant to be read from left to right, top to bottom. Concrete poets made work to be seen (and sometimes heard and touched), as much as to be read. Compositional tools that poets had long wielded, such as repetition and rhythm, assumed an overtly visual character. The directionality of text, the size and color of letters and words, and other aspects of typography all combined to generate intellectual meaning and emotional flavor.

The 100-plus works in the show, deftly curated by the Getty's Nancy Perloff and Christina Aube, feel fresh with the spirit of experimentation, invention and liberation. Playfulness and humor thread through the selection of books, prints, audio recordings and more. Some of the most affecting works extract remarkable graphic and emotional potential from just one or two words. In Mary Ellen Solt's 1964 "Zinnia," the word itself blooms in the dynamic spiral unfurling of its letters. Emmett Williams reconfigures the word "sweethearts" in a pithy, poignant 1967 book by that title, which comes with instructions on how to flip the pages. The motion conjured by a poem and the eye's pace traveling through it are key factors in the experiences offered here.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

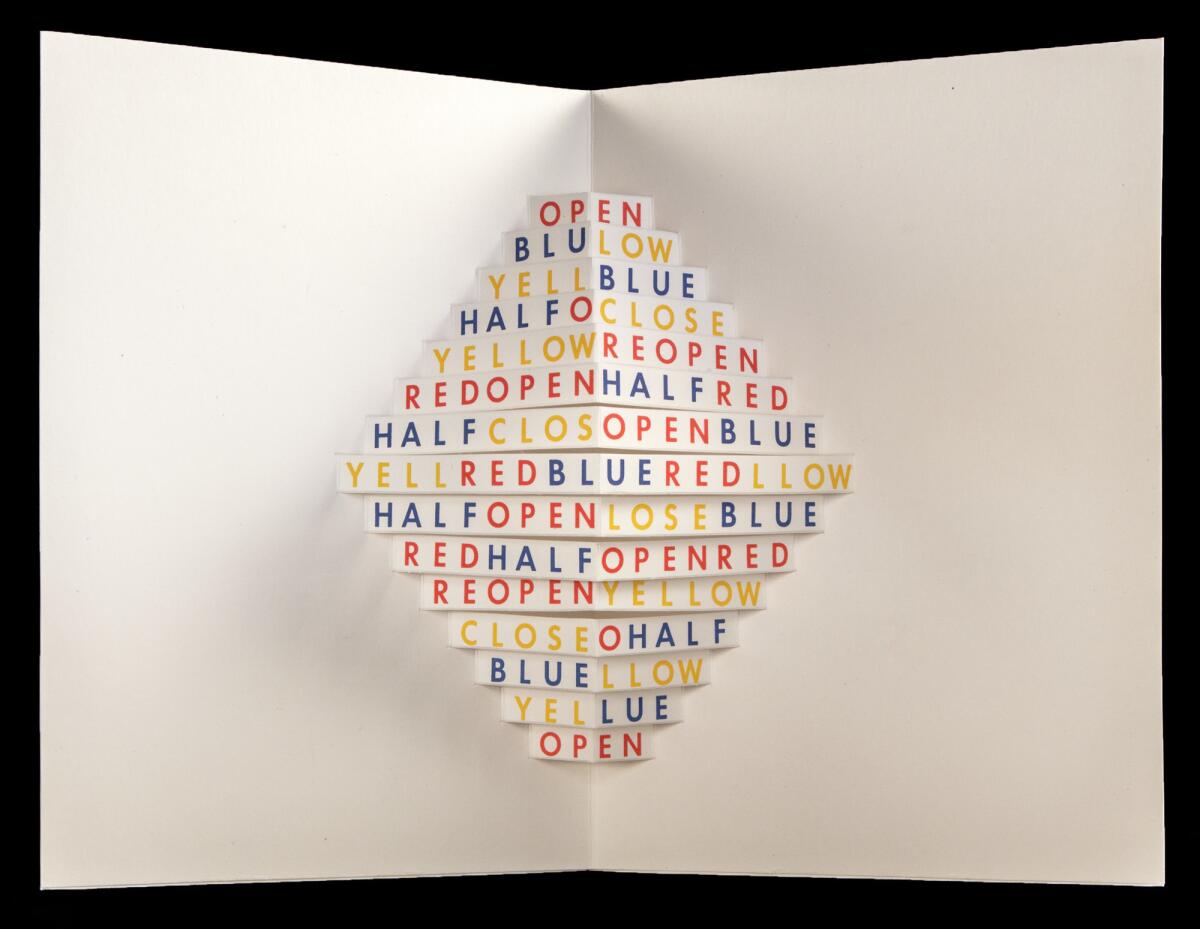

Ian Hamilton Finlay, one of two leading figures highlighted in the show, repeats in a striking lithograph the letters of "net" in alternating brick and black, line after line, so they accrete into the very weave they describe. Augusto de Campos, the other prime mover, is represented by an invigorating range of approaches to the sound and shape of language, from musical recitations to sculptural pop-ups.

Concrete poetry's roots in Futurism and Dada are nicely illustrated here, and the show asserts an affinity between the clever concision of these postwar works and the strategies of today's texts and tweets. Fertile ground lies also at the intersection of the materialization of language and the dematerialization of the art object in the '60s, where conceptual, text-based work emerges. The Getty show stirs a deep, full pot. There is no catalog, but the exhibition hand-out keeps this spicy snippet of history alive and within reach: a fold-up cube with all-over letters (by de Campos and Julio Plaza) that translate to read, "Everything has an (un)expected end."

Getty Research Institute, part of the Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Through July 30; closed Mondays. (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

MORE REVIEWS:

The Underdog on Post-it notes and other nostalgic bits, revived with a twist

A million points of dark: The thrilling pencil drawings of Eric Beltz

At LACMA, a don't-miss African art exhibition full of mystery and beauty

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.