How the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion won, then lost, the Oscars

- Share via

“Live from the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, California, the 71st annual Academy Awards.… Welcome to a star-studded evening here at the Music Center. The stars are out tonight to celebrate the best of the best…”

So crowed the cheerful ABC announcer at the top of the 1999 Oscars telecast as the camera prowled the red carpet.

It was the year that “Shakespeare in Love” trumped “Saving Private Ryan” for best picture and a highly animated Roberto Benigni climbed over rows of seats to claim an Oscar for “Life Is Beautiful.”

It was also the last year that the Oscars ceremony was held at the Music Center after a nearly three-decade run — the longest of any venue in Oscars history.

The Oscars broadcast was a publicity bonanza for the Music Center, providing the performing-arts venue with international exposure. For the academy, the center’s photogenic Midcentury architecture lent an air of class and sophistication to the annual ritual.

“It’s a very elegant facility, and I know the [board of governors] was originally attracted to it because of that,” said Bruce Davis, former executive director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

So why did the Oscars leave the Pavilion?

Leaders at both organizations recalled that scheduling had become an issue as the academy had to compete with the L.A. Philharmonic, L.A. Opera and other arts companies for use of the Dorothy Chandler.

“Between the Phil and opera schedules, as both of those organizations grew, it became harder and harder to carve out time,” said Howard Sherman, the Music Center’s chief operating officer. “At the same time, the Oscars production was getting bigger and bigger and needed more time for rehearsals.”

In the mid-’80s, the Oscars started alternating venues with the Shrine Auditorium near USC. Starting in 2002, the ceremony moved into its new permanent home at the Kodak Theatre (now the Dolby Theatre) at Hollywood & Highland.

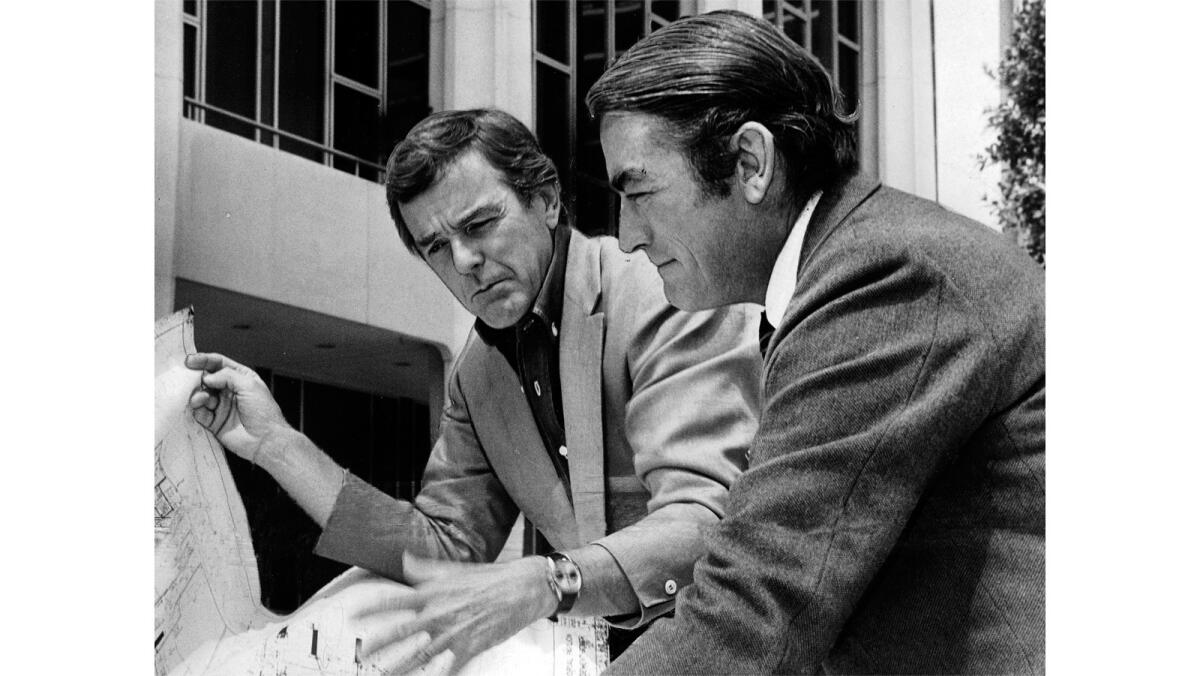

The Music Center first hosted the Oscars in 1969, when Gregory Peck was the academy’s president.

Until that time, the Oscars had led a somewhat nomadic existence and had most recently been held at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium.

Having opened to the public in 1964, the Music Center was a relatively new venue that boasted state-of-the-art facilities. It was Dorothy Chandler herself — the philanthropist and wife of former Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler — who helped secure her namesake theater for the academy.

“She became an ally,” recalled Walter Mirisch, the Oscar-winning producer and a former academy president. “We then needed to get it by the academy board and also the Board of Supervisors of the county. There was some opposition to it, and it didn’t go easily even with Buff Chandler’s assistance.”

Mirisch said there were questions about scheduling and how the Oscars would affect downtown traffic on Monday nights. He added: “Somehow or other, as in most of the things [Chandler] set out to do, with her help, we were able to accomplish it.”

Another advocate was theater and TV veteran Gower Champion, who was hired to direct the 1969 ceremony and insisted on the Dorothy Chandler. “I told them I’d do it only if we did the show at the Pavilion. The Music Center is the theatrical mecca of the West,” Champion told The Times that year.

The Oscars saw its share of memorable moments at the Music Center.

A male streaker dashed across the Dorothy Chandler stage during the 1974 telecast, prompting host David Niven’s famous line: “Probably the only laugh that man will get in his life is by stripping off and showing his shortcomings.”

Four years later, the mood was a good deal tenser when hundreds of demonstrators congregated in front of the Music Center to air their disapproval of nominee Vanessa Redgrave. Some accounts recalled that sharpshooters were posted on the roof of the Dorothy Chandler in case the commotion got out of hand.

Redgrave won a supporting-actress Oscar that night for “Julia” and her infamous acceptance speech — in which she used the term “Zionist hoodlums” — provoked boos from the audience.

There were also protesters in 1999 when director Elia Kazan received an honorary award. Kazan’s award was regarded as controversial because of his decision four decades earlier to inform on colleagues before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The Dorothy Chandler wasn’t built for television, and the Oscars often required the removal a significant number of seats to accommodate cameras and other equipment, according to Jeff Margolis, who has directed several Oscar telecasts.

But to Margolis, “It’s a perfect place for the Oscars — it’s elegant-looking on camera.”

In the mid-’90s, the academy was approached by property developer TrizecHahn about the possibility of working together. Out of those conversations came the idea of building a theater solely dedicated to the Oscars in Hollywood.

“It was appealing to us to have our own theater. We could control our own dates and didn’t have to coordinate,” said Robert Rehme, a former academy president.

The Kodak Theatre hosted its first Oscars in 2002. The theater, now owned by CIM Group, was designed for the Oscars telecast and features a slightly larger seating capacity than the Dorothy Chandler.

Leaders at the academy and Music Center said that their parting of ways was amicable. However, when asked if he saw the Oscars’ move to Hollywood as a loss, Sherman, the Music Center’s COO, replied, “Absolutely.”

“To have that national exposure for an event like the Academy Awards was unquantifiable,” Sherman said.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.