Review: The Allen Ruppersberg show at the Hammer Museum is a don’t-miss tour de force

- Share via

When “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” Oscar Wilde’s only novel, was published in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine in July 1890, London critics furiously attacked the author. “False art,” said a notorious review in the Scots Observer, which went on to accuse Wilde of gross immorality.

The writer famously shot back, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book.” Offering up a sharp defense of art for art’s sake in his Gothic novel’s withering repudiation of Victorian prudery, he declared, “Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

I’m not aware of any such critical slam aimed directly at Allen Ruppersberg for his fantastic 1974 work based on Wilde’s novel — although Conceptual art was then certainly under furious establishment attack. It’s just as well. This version, a highlight of the artist’s deeply engaging retrospective at the UCLA Hammer Museum, is a masterpiece of early Conceptual art.

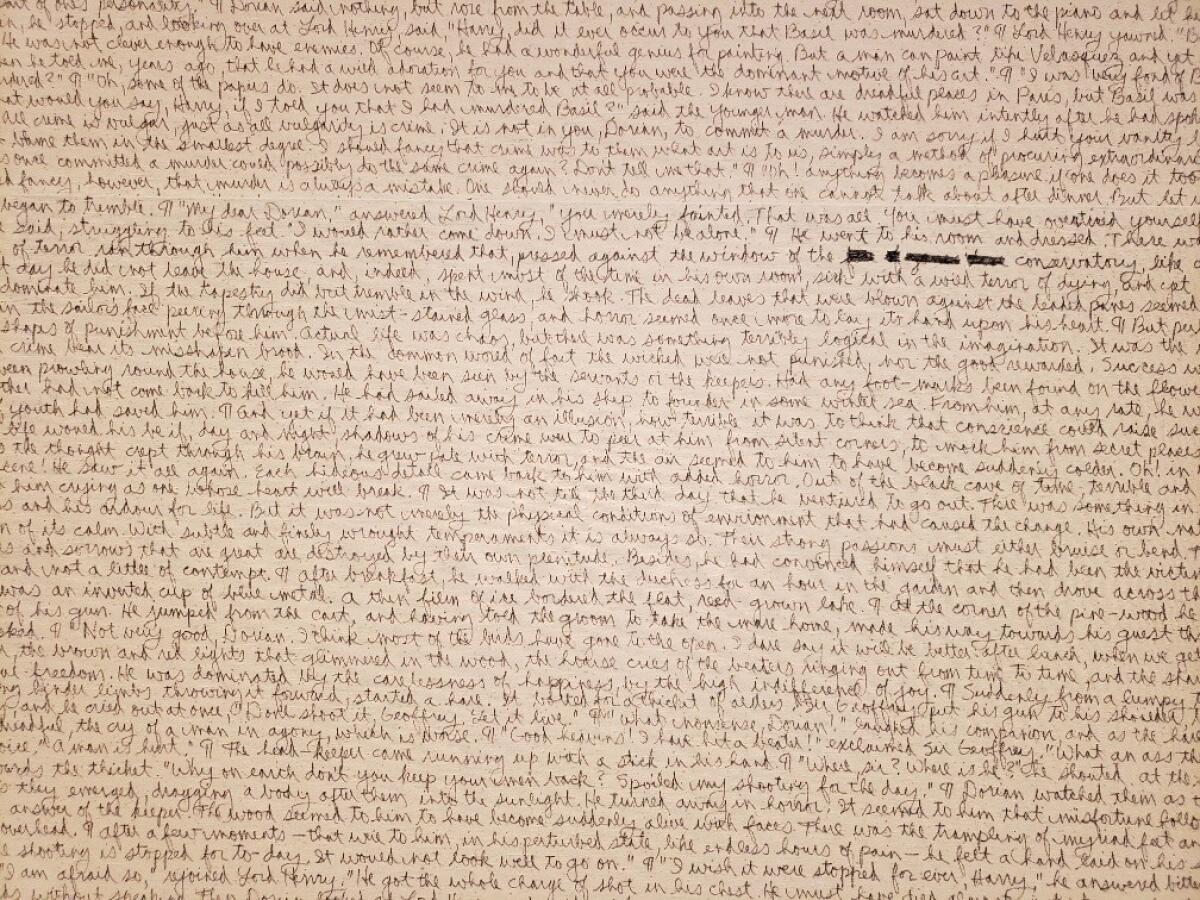

“The Picture of Dorian Gray,” a peak achievement made near the end of the movement’s powerful first phase, is a cornerstone of Ruppersberg’s impressive career. In it, the artist hand-copied Wilde’s entire Faustian text, word for word, in felt-tip pen onto raw, stretched canvases. Once in a while he messed up a word, crossed it out, and then continued on.

In the book, Dorian Gray is the subject of a painting by Basil Halliwell, an artist obsessed with the young man’s physical beauty. When Dorian falls into a life of sensual hedonism, he sells his soul so that the painted portrait will age and decay, while he retains an ageless magnificence.

Things do not go well.

Each of Ruppersberg’s 20 canvases is 6 feet square. Unlike Halliwell’s picture, which got locked away in a closet to rot in private, they take up a lot of space.

The work has been described as a painting about a book about a painting. Since no paint is involved, however, I’d say it’s more like a drawing about a book about a painting. Drawings were once mostly made as preparations for paintings, but this one pulls up short.

It’s a study that conjures a fictional painting. Wilde imagined it as a critical template for moral duplicity — for the ruin caused by a double life, one played out in public and the other hidden away in private. As Ruppersberg drew in 1974, America was melting down in the scandalous revelations of Richard Nixon’s Watergate crimes. That history gives the piece powerful resonance for our grinding national disorder today.

Ruppersberg has made lots of drawings of books over the years — Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea,” “The Elements of Style” by Strunk & White, Horatio Alger’s “Strive and Succeed” and Charles Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du Mal” among them. Those books’ subjects — nature, technique, success, symbolism — catalog art’s dilemmas.

I know of only one major painting of a book — “Greetings From California,” a 1972 acrylic on canvas that shows a bright orange tome, tagged “a novel by A. Ruppersberg,” floating peacefully in a dark blue sky over a silhouetted hill at sunrise. Look twice and the breaking dawn resembles a breaking ocean wave, the book its surfboard. Closed and enigmatic but waving hello like a postcard from the edge, the painting was accompanied by an edition of 200 paperbacks, most of their pages left blank.

Los Angeles, proverbial place for reinvention, a city claimed to be without a past, presents a story waiting to be written. Born in Cleveland, Ruppersberg, now 74, moved to L.A. to study commercial art in 1962. He’s divided his time between L.A. and New York ever since, interspersed with some European sojourns. “Greetings From California” hangs at the exhibition’s entrance.

The show offers a rare opportunity to see his early work. Especially pungent is a group of five small aquariums with mundane objects inside — gravel, a little bird house, a box of chocolates, a coin purse holding a eucalyptus leaf atop a sheaf of paper and more.

My favorite features a small blank canvas on a barren little plain of pebbles. Each aquarium is a poetic universe — a cross between a Surrealist box by Joseph Cornell and a soundstage at a Hollywood studio.

The aquariums were harbingers of two legendary Ruppersberg installations. “Al’s Cafe” was a functioning coffeeshop the artist opened near MacArthur Park, although the menu featured small assemblage sculptures rather than bacon and eggs. “Al’s Grand Hotel,” perhaps inspired by the old Barbizon Hotel next door to the café, was a functioning Hollywood inn with rooms to rent.

The café and the hotel precede by 20 years the 1990s vogue for so-called relational art — sculptures built as social environments, places where people come together to participate in shared activities.

The hotel is gone but nicely evoked in the exhibition by a slide show of photographs projected onto surrounding walls in a small room. It suggests how the installation led a double life — an actual social space and a work of art.

So do the drawings, although more elliptically. Drawing is a staple of Conceptual art because it most closely tracks an artist’s unfolding thought, from brain to hand to surface. Ruppersberg’s graphite book-drawings are ruminative in the extreme.

Their content is hidden, since a picture of a book cannot be opened. But they do have internal meanings, which can be found outside themselves by searching out the actual texts. Ruppersberg’s drawings catalog art’s dilemmas, but the pictures urge an observer to explore those quandaries too.

Time unfolds in space — dramatically so in his “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” All those canvases lean against walls, stacked up and occupying a whole room. The hand of the artist is omnipresent, thanks to the autograph penmanship.

But Ruppersberg’s visible hand is layered over Wilde’s invisible one — as well as over fictional Basil Halliwell’s, the novel’s portrait painter. The present and the past, the real and the imaginative are embodied. Art generates art.

“Intellectual Property,” ably organized by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, is a welcome sequel to Ruppersberg’s 1985 midcareer survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art. It’s a blissful retrospective, art revealed as delighted exploration of sober matters.

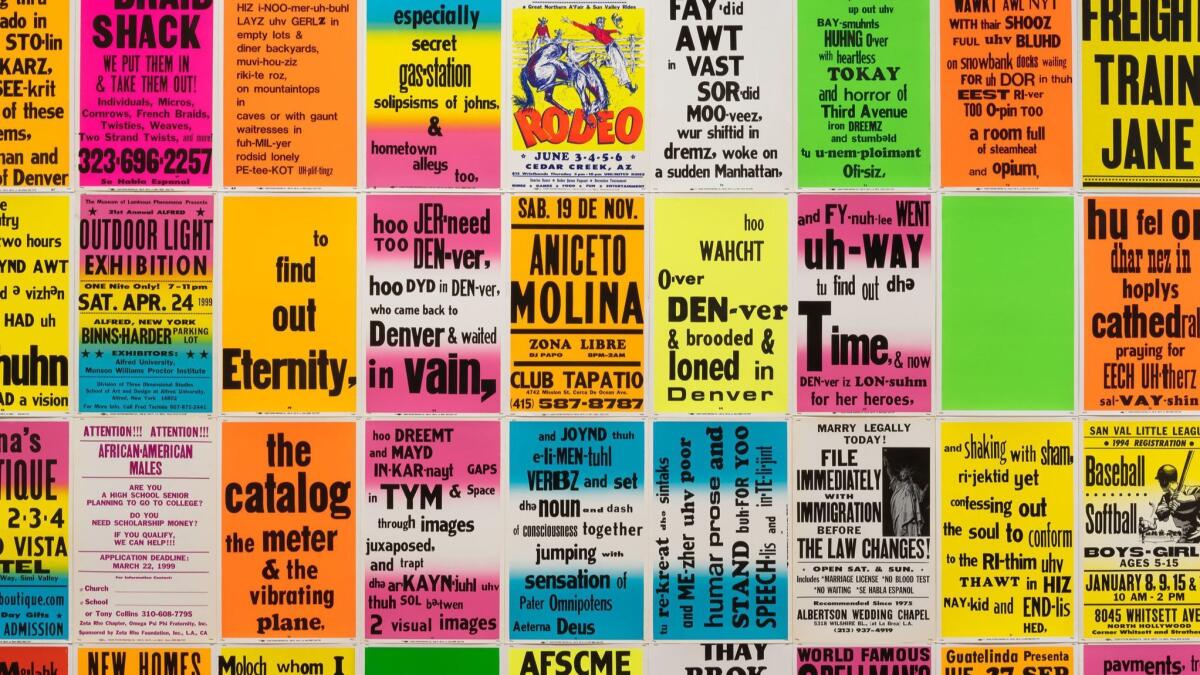

That includes the Day-Glo posters papering walls, which the artist began to produce in the mid-1980s. (He stopped in 2012, when L.A.’s Colby Poster Printing Co. went out of business.) Based on the familiar, cheaply made signage that turns up on telephone poles and fences to advertise prizefights, church carnivals and swap meets, they’re ancestors of Mark Bradford’s very different, more recent paintings produced from thickly collaged, handmade street signs.

The big example here — a tour de force — mixes found commercial posters with Ruppersberg’s own graphic interpretation of a phonetic reading of “Howl,” Allen Ginsberg’s Beat-era lament for America’s outcasts. Like “Dorian Gray,” Ginsberg’s 1956 poem was first attacked as obscene, then worked its way into history’s canon through the sheer force of its artistic power.

That trajectory makes “Big Trouble,” a 2010 installation at the end of the show, especially trenchant. Cutouts feature Scrooge McDuck imagery plucked from 10 framed prints of a classic Disney comic strip. They track the buffoonish competition among mega-rich characters to erect the biggest, most expensive statue to honor their own self-importance.

The notably gray statue cutouts are plywood stage flats, the big-bucks contest turned into a cut-rate theatrical spectacle. The colorful framed comics, now missing the statue images, are full-throated works of art rendered by gifted if little-revered draftsmen.

As a wicked allegory of today’s rapacious art world, a tale of ever larger and more extravagant statues to Cornelius Coot erected by McDuck and the Maharajah of Howduyustan is hard to beat. And a remarkable loop is created: Enclosed is the arid landscape inside that early aquarium at the show’s start, plus the story of ruinous decay in Wilde’s “Picture of Dorian Gray,” so harrowingly inflamed during an earlier Gilded Age.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Allen Ruppersberg: Intellectual Property 1968–2018’

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Tuesdays-Sundays, through May 12

Information: (310) 443-7000, www.hammer.ucla.edu

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Ruppersberg at the Santa Monica Museum of Art in 2009 »

DESERT X: I drove 198 miles to see 19 artists’ work. Here’s the best »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.