For Alain Boublil, the man behind ‘Les Misérables,’ the revolution isn’t over

- Share via

Alain Boublil is 78 but looks younger in person, trim and lithe in the way of French cinema stars. The librettist and lyricist, who with composer Claude-Michel Schönberg wrote two of the longest-running musicals of the 20th century, “Les Misérables” and “Miss Saigon,” guides a reporter up the stairs of his Nichols Canyon house to the second-story office, a small, uncluttered room with a sofa, a desk and a modest selection of posters advertising different productions of “Les Mis,” including the 2012 movie.

But the first thing the two-time Tony winner wants to show off is a 2019 award certificate for best music video from the Los Angeles Film and Script Festival. The video is for the pop single “Is This Love?” written and performed by Maxime Boublil and directed by Adrien Boublil — Alain Boublil’s sons, who are in their early 20s and live in L.A.

“We just attended the ceremony. It’s exciting for the parents,” Boublil says.

It’s because of Adrien and Maxime that Boublil and his wife, Marie Zamora, who originated the role of Cosette in the French production of “Les Mis,” bought their L.A. house about a year and a half ago. By coincidence, touring revivals of his biggest hits are stopping this summer at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre — “Les Mis” now through June 2 and “Miss Saigon” in July. Of course it might be hard to find a city where these musicals were not scheduled to play.

Box-office smashes upon their London premieres in 1985 and 1989, respectively, the shows have inspired generations of devotees and detractors and so thoroughly saturated the culture that it’s impossible to imagine the theatrical landscape without them.

I was speaking with Taylor Swift one day, and she said, ‘I was 13, and I was singing “On My Own” before I started to write my own songs.’

— Alain Boublil, librettist and lyricist

As he takes a seat on the sofa, Boublil admits he’s a bit jet-lagged. He lives mostly in New York, but he enjoys spending time with his family in L.A. and advising his sons in their ventures into the world of pop music, where he started his career.

“I started writing pop songs at the very, very beginning in France. And by the way, so did Claude-Michel,” he says. “So we both come from the pop songwriting world in France, in the ’70s. “Until I discovered my own attraction for musical theater, and that was like a disease.”

Although this remark comes across as a joke now, Boublil and Schönberg’s affliction did once set them apart from their countrymen.

The American-style musical had no counterpart in France. Musicals on film were popular, “but never on a stage,” Boublil says. “No one had ever brought them to France, or tried to, because there was no structure. There was not the right kind of theaters, there were no producers, there was no taste for that, and there was no tradition for that. You have such a strong tradition in America, which starts at school. Every child does musicals at school or at summer camp. It’s like ingrained in their bones, in their DNA.

“I was speaking with Taylor Swift one day, and she said, ‘I was 13, and I was singing “On My Own” before I started to write my own songs.’ That doesn’t exist in European countries. It’s starting, but it didn’t exist back then.”

He doesn’t remember exactly when “West Side Story” toured France — late 1960s or early 1970s, when he was in his late teens. The tour wasn’t a success, he says, but when he saw the show, he thought: “This is what I’ve been wanting to do all my life. Watching the first musical of my life, watching the geniuses of Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins and Stephen Sondheim accomplish an update of ‘Romeo and Juliet.’ I thought, ‘What is … How do you do that?’ And it felt like something impossible to do.”

A few years later in New York, Boublil saw “Jesus Christ Superstar,” the rock opera that launched the careers of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. Lloyd Webber and Rice had started out in songwriting too. And it struck Boublil that creating a rock opera, and borrowing the “Superstar” team’s strategy of producing a concept album, then staging it as a musical, might help French audiences acclimate to the art form. He even had an idea for a subject: the French Revolution.

“So here’s how the first show was born,” Boublil says. “I came back to Paris, told about all my discoveries to my friends with whom I used to write pop songs, and I could see in their eyes both the curiosity and also thinking that I was going mad. But at the end they said, ‘Why not?’ And so the composer I used to work with said, ‘But what you are asking is too complicated for me on my own. Let’s call Claude-Michel, who is a mad opera fan.”

The album “La Révolution Française” and the ensuing theatrical concert — held in the Palais des Sports in Paris — were enormous successes. “People were curious to understand,” recalls Boublil. “What have they done? Why do you sing the French Revolution? Why is Robespierre singing on that stage? Why is the queen of France singing before she’s going to be decapitated? Which, when you think about it, just doesn’t make sense.”

After the show closed, Boublil, Schönberg and co-creators Raymond Jeannot and Jean-Max Riviere went back to their day jobs. The disco era was dawning. Only Boublil and Schönberg wanted to keep making musicals.

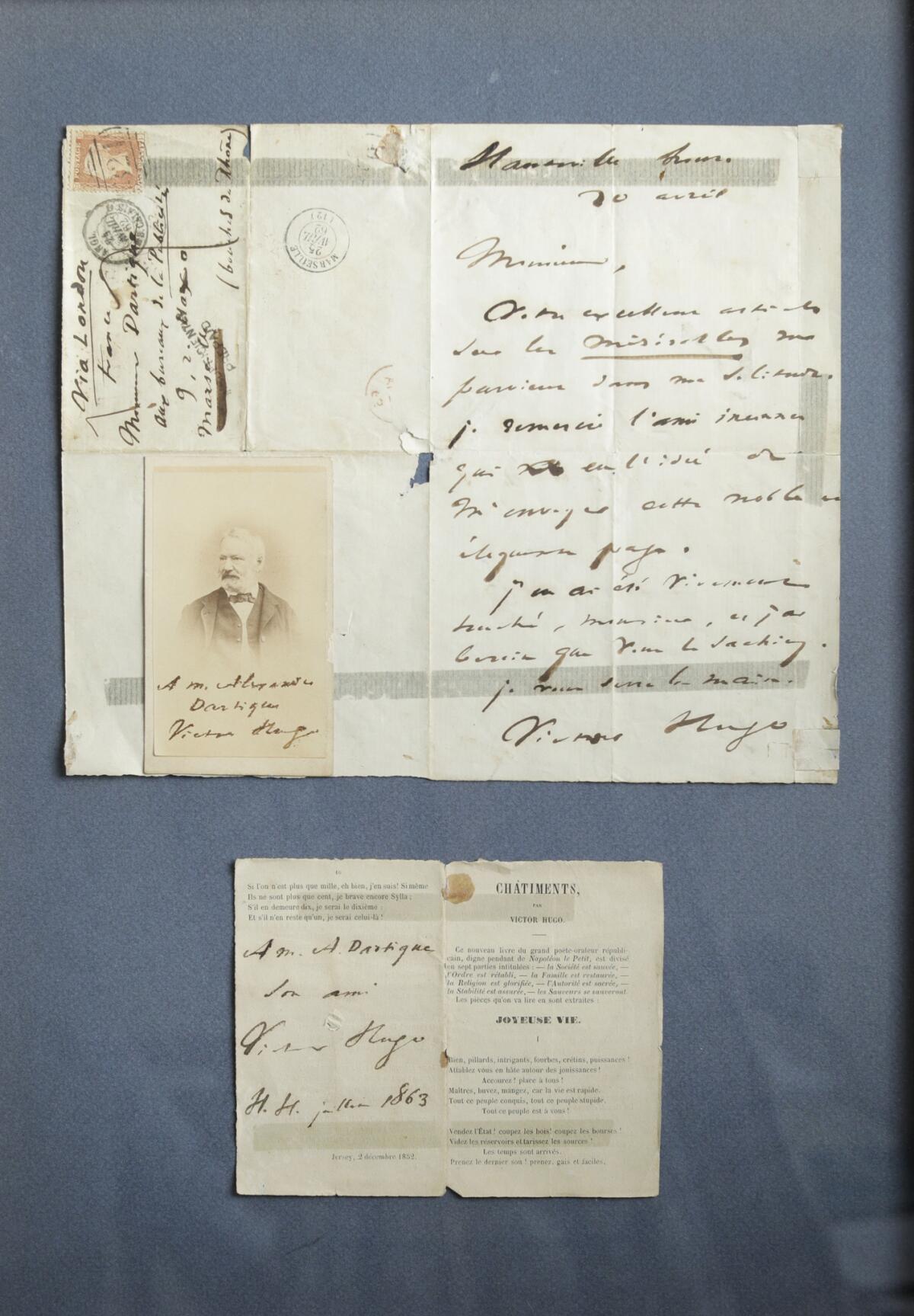

A few years later, while Boublil was watching “Oliver” in London, the young character known as the Artful Dodger made him think of Gavroche from Victor’s Hugo’s novel “Les Miserables.”

A DTLA SPECIAL: The past, present and future of Grand Avenue »

“Little by little, I started really to see two shows on that stage,” Boublil says. “One was ‘Oliver,’ playing in front of me, and the other one was, like, in the stage of my head, and I was seeing Valjean, Javert, Cosette. I was lucky the day after to find a copy of the novel in the library in Old Compton Street. I just made a few notes. There was a chapter called ‘J’avais rêvé d’une autre vie,’ and I thought, ‘That’s a song.’ And it became in English the song ‘I Dreamed a Dream.’ ”

Boublil and Schönberg immediately quit their jobs to work full time on “Les Misérables.” Within two years they had it written, recorded and staged — again at the Palais des Sports. Once again, the show did well, but after it closed as scheduled, nobody expressed any inclination to do anything more -- until producer Cameron Mackintosh called three years later.

“I didn’t know who he was,” Boublil says. “And he said, ‘I think you have created a musical. I heard the record last night at a friend’s house. You know, I think you have written something very exceptional. You may not realize it, but I need to come to Paris and see you.’ And he said to me, ‘I’m the producer of ‘Cats.’ ”

Boublil makes a uniquely French sound at this point: a kind of “pfft.”

“I didn’t know what ‘Cats’ was,” he says wryly. “And neither did Claude-Michel. But we met Cameron, and he introduced us to the English team, who happened to be the most brilliant representatives of the English musical theater, each one in his category, and that’s how suddenly we came from knowing no one and having to do everything ourselves to being plunged into English musical theater royalty.”

Boublil and Schönberg have been collaborators for more than 40 years. They are usually photographed and interviewed together, and Boublil speaks of Schönberg so often that “we” is just as likely to mean “Claude-Michel and I” as “my family and I.” At times it almost feels like Schönberg is in the room too.

“I wish he were,” Boublil says. “We speak every day,” he reassures me. Their partnership has been so fruitful and harmonious, he speculates, because they both believe that a musical’s book must be “perfect.” No matter who comes up with the concept — Boublil thought of “Les Mis,” whereas Schönberg had the idea of relocating Puccini’s “Madame Butterfly” to war-era Vietnam for “Miss Saigon” — they take their time to develop the book together, adapting and structuring the source material until the storytelling pleases them both.

“When we have failed, it’s because the storytelling is not right,” Boublil says. “And we don’t give up, meaning we’re still working, until we get it right, and that’s ‘Martin Guerre.’ That’s what we’re working very hard on at this moment, because we believe it’s very close.”

The duo’s third musical, inspired by the 1982 French film “Le Retour de Martin Guerre,” opened in London in 1996. It hasn’t yet found the success of its predecessors. But a rejiggered version may be seen in London “within the next two years,” Boublil says. He and Schönberg are also working on another project, about which Boublil apologetically says he is obliged to be vague. It may have something to do with Hollywood, and one of their shows.

He’s working on something of his own too, but he declines to talk about it in this article.

“I think this would be a little bit discourteous to Claude-Michel,” he says. “Oh, he knows about it! He knows about everything. But this story should be about him and me.”

=====

Alain Boublil

Where: Hollywood Pantages

When: “Les Misérables” through June 2; “Miss Saigon” July 16-Aug. 11

Tickets: $49 and up (subject to change)

Info: (323) 468-1770 or hollywoodpantages.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.