A powerful symbol of resistance, the Underground Railroad inspires a wave of books, plays, TV and more

- Share via

When WGN America’s drama “Underground” debuted last winter, it seemed like a cultural outlier. Stories from the Underground Railroad had long been relegated to nonfiction or the broad and simplistic brushstrokes of children's books. Even as stories about the horrors of oppression (“12 Years a Slave”) and the civil rights movement (“42,” “Selma,” “All the Way”) entered the mainstream, the Underground Railroad remained overlooked.

Lately, however, slaves’ flight to freedom has became a jumping off point for an array of creative endeavors. A few weeks after “Underground,” with its soundtrack curated by executive producer John Legend, came Barbara Hambly's mystery novel, “Drinking Gourd,” and Robert Morgan's escape saga, “Chasing the North Star.” Last summer Ben Winters’ counterfactual noir novel, “Underground Airlines,” hit bestseller lists; then came Colson Whitehead's “The Underground Railroad,” the year's National Book Award winner for fiction.

In the fall, the surreal and subversive “Underground Railroad Game” opened to rapturous reviews off-Broadway. (The New York Times called it “in-all-ways sensational.”) Set in the present, the play depicts two teachers, one white and one black, stumbling along the treacherous path of educating children about slavery and racial oppression.

The topic “hasn't been explored enough so I'm not surprised people are finding new and different angles,” says “Underground” co-creator Joe Pokaski.

This month brings a new season of “Underground,” the opening of the National Park Service’s

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

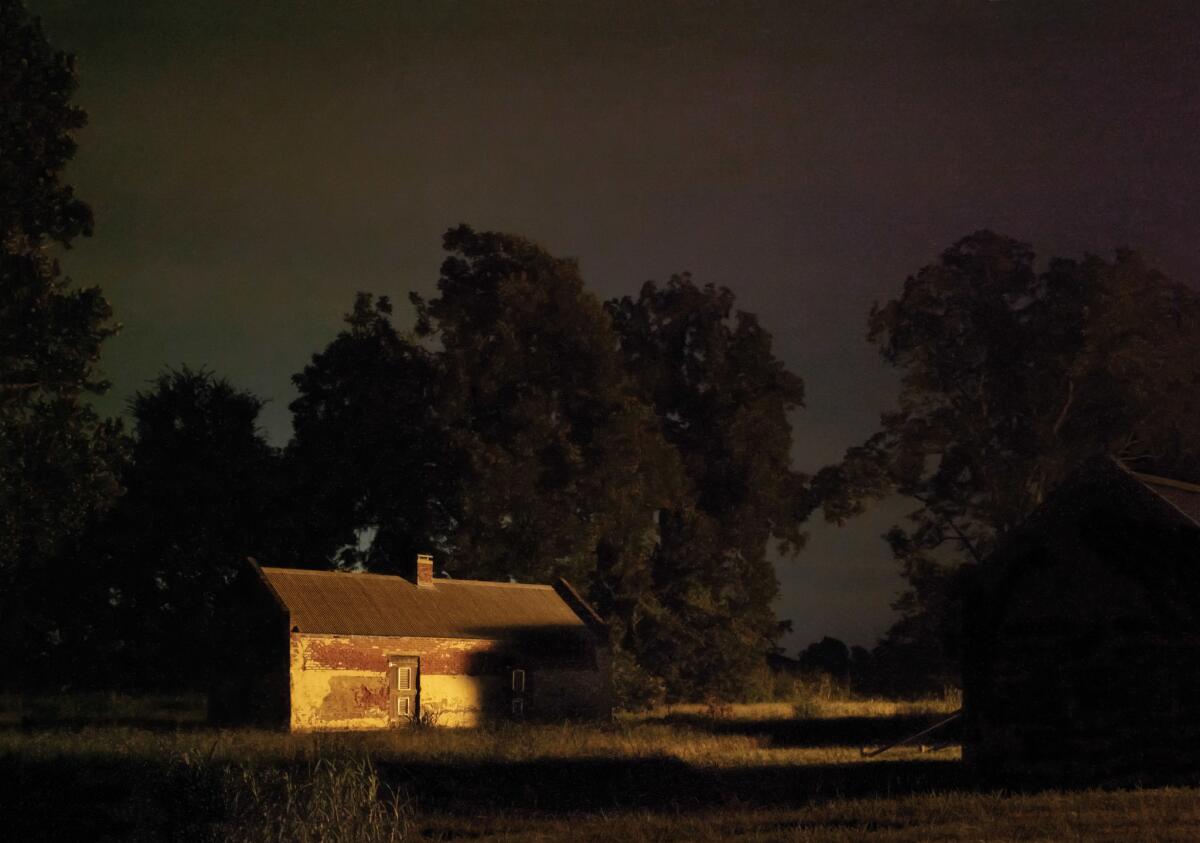

“The Underground Railroad came at a time when our country was so polarized that there was no understanding on either side so the fascination with it now might be because we're back in that situation,” says Michna-Bales, adding that the movement also blurred lines, bringing together white and black, and people from different religions and socioeconomic groups, while also giving women previously unheard of roles in public life. Her pictures aim to provide a first-person perspective on what a slave would have seen on the long and dangerous journey north.

Many more slaves actually attempted escape without the aid of the Underground Railroad, at least initially. The phrase Underground Railroad first appeared around 1839 but slaves had, naturally, been trying to escape since the implementation of this horrific institution. Many initially tried for Mexico or the Caribbean. Historians estimate that the railroad helped 30,000 to 100,000 (of the millions of enslaved blacks) to escape to Canada. But for the most part the railroad really ventured only about 100 miles into the South, so the first season of the TV series and Morgan's novel also explore the experience of slaves running without outside help.

“Underground” co-creator Misha Green puts all these new works in the larger context of publishers and producers recognizing the value — artistically and commercially — in stories about minorities, from the “Roots” remake to Oscar best-picture winner “Moonlight.” She points particularly to ones with characters seizing control of their own narrative, whether that’s “Straight Outta Compton” or “Hidden Figures.” Indeed, last year also begat a movie (“Birth of a Nation”) and a play (Nathan Alan Davis’ “Nat Turner in Jerusalem”) about Turner's slave uprising.

Author Morgan, a professor at Cornell University, says the trend's roots stretch back decades.

“Fiction is the way we learn about others,” he says, pointing to waves of groups laying down their markers, from Southern writers in the 1930s to Jewish writers in the decades after World War II. “The original 'Roots' was the building block and writers like Alice Walker, Toni Morrison and August Wilson then paved the way,” he says, so that these Underground Railroad stories are a natural evolution.

“I think it's a good thing any time people are interested in history,” says Eric Foner, a leading scholar of 19th century America, whose 2015 book, “Gateway to Freedom,” focused on the Underground Railroad. Foner understands artists taking liberties with the facts, and he admires Whitehead's fantastical creation of an actual railroad that runs underground. “It's fantasy but Whitehead also gives a kaleidoscope of black history. It's very informed.”

Most of the current projects began a few years ago, so Green says the zeitgeist partially reflects the rise of the tea party and birther movement followed by the spate of police shootings and the birth of Black Lives Matter.

“These stories, like police brutality, have always existed but now the public might finally be primed and open to step outside its own orthodoxy and turn its gaze to them,” adds “Underground Railroad Game” co-writer and costar Jennifer Kidwell.

Even as these stories make history more accessible to mainstream audiences, they’re refusing to whitewash the grim realities, striving instead to demolish the traditional narrative. “This is not your grandfather's history that helps paint a rosier picture of historical atrocities,” says Scott Sheppard, co-writer and costar of “Underground Railroad Game,” which will tour to as-yet-undetermined destinations in late 2017 and 2018.

“We often use narratives as balms to sooth our concerns and fears about where we are now,” Sheppard adds. The number of escaped slaves is minuscule compared to the systematic destruction of the millions of lives throughout slavery's history, so “we want to remove that layer of romanticism and make everyone question their beliefs and values in as destabilizing a way as possible.”

The effects of and resistance to that oppression and the lasting legacy are a foundation of who we are as a people.

— Ben Winters, author of "Underground Airlines"

“Underground” may be slickly produced adventure TV yet one main character after another gets recaptured or killed. In “Drinking Gourd,” protagonist Benjamin January, a thoughtful and well-educated free black man, reflects on how he has come to hate virtually every white person, especially after learning the white abolitionist he encounters rapes the girls he helps to freedom. Whitehead's and Winters' novels are even darker.

“Underground Airlines” takes place in the present but imagines a world that had no Civil War, where slavery was only gradually abolished and where it still thrives in four Southern states. “I'm hoping the book is a reminder of the presence of the past in our lives,” says Winters, who connects a nation built on slavery to the institutionalized racism that persisted through Reconstruction and Jim Crow and that continues today. “My alternative history isn't alternative enough.”

“Underground Railroad Game” also ties the sins of America's past squarely to the present day.

“Our play explores the myths of the white savior and of romanticized American history,” Kidwell says. “We just happened to set it against the Underground Railroad.”

That is a recurring theme in interviews with the writers, especially those who are white.

“It's important that these stories are not, 'Oh, these nice white people are helping these poor black slaves get away’ and are instead about free blacks and slaves taking agency,” Hambly says.

In Winters’ novel, the idea of whites as nobles rescuing the helpless is derisively called the Mockingbird mentality, in reference to Harper Lee's Atticus Finch.

“We are not just telling a black story,” Winters says. “Slavery is a story about white America; it's about the role that people who looked like me played — and still play — in oppressing people who look different. The effects of and resistance to that oppression and the lasting legacy are a foundation of who we are as a people.”

Although these works were all conceived before

“They will resonate differently,” says musician Legend, who not only served as music curator and executive producer on “Underground” but also plays Frederick Douglass this season. “We have a president who doesn’t know anything about American history or black history, and people are starting to realize how important it is to understand our history so we can fight back.”

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Getty acquires trove of work by 17 influential photographers

MOCA gift consists of 22 key works exploring gender and queer identity

Diego Rivera's Cubist masterpiece arrives at LACMA

'Zoot Suit': How Latino theater born in the farm fields changed L.A. theater

MLK's speeches translated into dance

Architecture's highest honor nods to the forces behind Brexit and Trump

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.