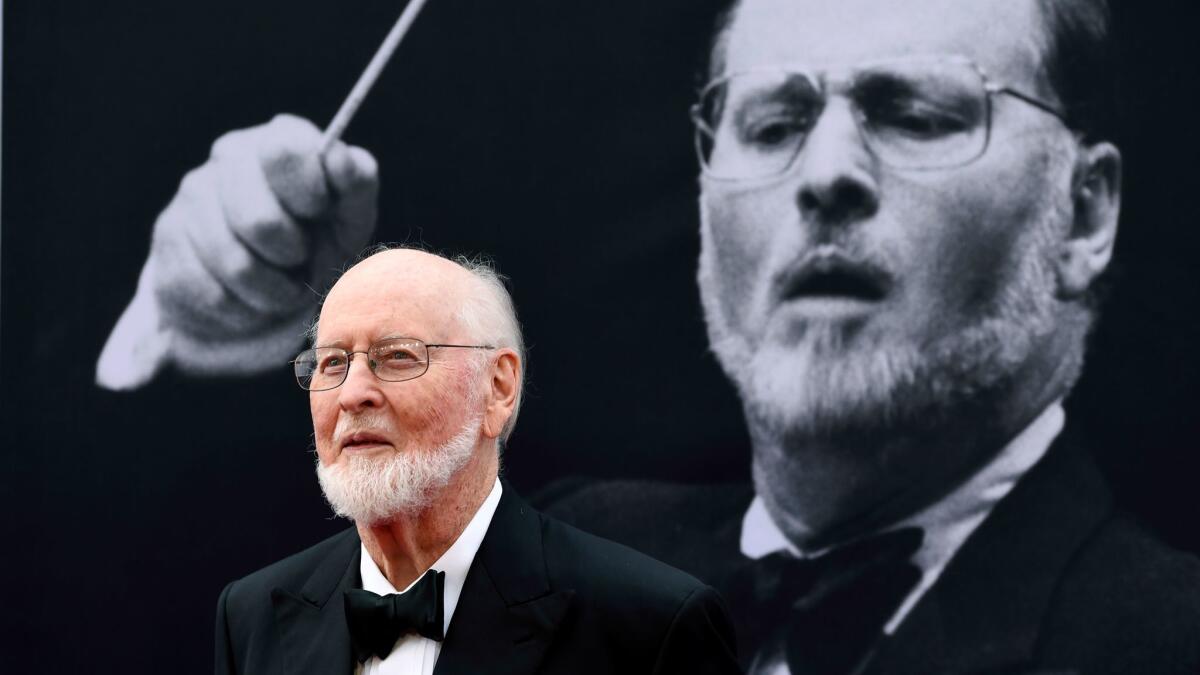

Perspective: How much gold can lie in 45 Oscar losses? In the case of John Williams, the answer is: Tons

- Share via

Consider these numbers: 86, 60, 51.

That’s how old John Williams is, how many years he’s been composing for film and television, and how many Oscar nominations he has earned.

It adds up to a staggering, unprecedented career — one that’s easy to take for granted. But what’s downright incredible is that we are still living in the Williams era. On Sunday he’ll be at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood once again, a contender for his music for “Star Wars: The Last Jedi” — his eighth score for the franchise, and his fifth time nominated for it.

The composer earned his first Oscar nod 50 years ago for adapting André Previn’s songs into the score for “Valley of the Dolls.” Those 1968 Academy Awards, at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, were postponed for two days because of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Williams’ Oscar wins are, with one exception, for films that you might expect: “Jaws,” the original “Star Wars,” “E.T. the Extra Terrestrial” and “Schindler’s List.” (His first statue, in 1972, was for adapting the Jerry Bock songbook for Norman Jewison’s “Fiddler on the Roof.”)

But what about those 45 “losers”?

They too read like a greatest hits album: “Superman,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Home Alone,” “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.”

I always thought that John Williams ... is probably the person that’s most singularly responsible for the enormous impact those films had on culture.

— Mark Hamill on the composer’s work for the “Star Wars” franchise

Williams has achieved GOAT (Greatest of All Time) status partly by hitching his wagon to Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and some of the biggest blockbusters in movie history. But the composer’s success also stems from his unparalleled gift for pop-like melody.

It’s striking that you can read John Williams’ credits and immediately hear so many tunes in your head. His lyricism and catchy hooks not only gave a movie its distinct signature but also could turn a film-going memory into an earworm. That accounts for a great deal of his popularity and staying power, on full display every year at the raucous, sold-out Hollywood Bowl shows he conducts. He is a rock star.

But what many may not fully appreciate is that he’s not merely a tunesmith. Williams taught himself orchestral arranging while he was still in high school, gobbling up the notes and nuances of the classical repertoire. While studying at Juilliard, Williams moonlighted as a jazz pianist in nightclubs, and those two skills — formal and footloose — created an alchemy for film scoring.

His intimate knowledge of what an orchestra can do has been put to use in the freaky, avant-garde score for Robert Altman’s “Images” in 1972 and his decidedly different opus for Rob Marshall’s 2005 drama “Memoirs of a Geisha,” not to mention his psychedelic concerto for Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” (In that film, tellingly, advanced intergalactic communication is the music of John Williams.)

His jazz background is there in most scores, in the complex harmonies and infectious riffs. Even when a Williams tune sounds simple, a close analysis reveals a complex swatch of hues. He really lets it fly in the fingersnaps-and-sax score for “Catch Me If You Can.”

He can effortlessly shapeshift into Americana (“The Reivers” and “Lincoln”), Africana (“Amistad”), Judaica (“Schindler’s List”), Irish folk (“Angela’s Ashes”) or Britten-esque English (“War Horse”).

Where Williams truly reveals himself as the consummate film composer, though, is his understanding of the art form. He’s a storyteller.

“He doesn’t just create and write because it’s a film he’s been hired to do,” Richard Donner, the director of “Superman,” said in an interview. “He really becomes the film. He’s inside the characters. He’s inside the emotion.”

In “E.T.,” Williams begins the score with nothing but eerie ambience. Slowly, subtly, he plants seeds of the main “Flying Theme” as E.T. and the boy Elliott get to know each other. When it erupts for the famous bike ride against the moon, the audience has been anticipating an emotional catharsis without even realizing it.

Or take the scene in “Empire of the Sun” when the young prisoner of war played by Christian Bale, an airplane enthusiast, runs to the rooftop as American pilots fly in to liberate the camp. Williams’ music captures the angelic majesty of the planes soaring in slow motion and the euphoria of Bale’s almost feverish Jim, turning the moment into a religious experience.

As for “Star Wars,” just ask Luke Skywalker.

“Speaking as honestly as I can,” actor Mark Hamill told me last year, “I always thought that John Williams, next to George [Lucas], is probably the person that’s most singularly responsible for the enormous impact those films had on culture.”

Many of today’s film composers went into the field because of Williams. Alexandre Desplat, a challenger this year with his score for “The Shape of Water,” has called Williams his idol.

With the fans have come some detractors. They say Williams is derivative or that all of his scores sound the same. Merely listening to his Oscar-nominated work, let alone all 100-plus features on his CV, debunks the latter.

His style of pure, liquid emotion — particularly for the films of Spielberg — rubs some critics the wrong way, and there’s no denying that the duo is in the business of making audiences feel. Spielberg once said that Williams “can take a tear that’s just forming in your eye, and he can cause it to drip.”

But this complaint ignores Williams’ facility for nuance. Just listen to his intimate, melancholy score for “The Accidental Tourist” or the dark and complex “Sleepers.”

Williams, whose career overlapped with old-school masters like Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Newman, still writes with pencil and paper, sitting at a piano. But the day will come when we won’t have a new score to savor anymore, when a new “Star Wars” film is merely copying the master’s musical voice, when the seats at the Academy Awards are filled only with the many composers he influenced and inspired.

Perhaps only then will we appreciate just how lucky we are to live in the era of John Williams.

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

MORE OSCARS COVERAGE:

From ‘Three Billboards’ to ‘Last Jedi,’ movie music gets the Disney Hall spotlight

Why ‘Three Billboards’ and ‘Call Me by Your Name’ leave this theater critic cold

Times critics Justin Chang and Kenneth Turan in conversation

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.