What’s next for the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time? This critic has an idea

- Share via

In many major cities, art life marks time with annual commercial art fairs or contemporary biennials. These events have their pros and cons. L.A. is unique, however, thanks to the acumen and generosity of the Getty Foundation.

In six short years, Pacific Standard Time, the Getty-sponsored initiative to explore the history of art as it relates to Los Angeles and Southern California, has become an essential feature of the region’s art life. Three installments since 2011 — two extravaganzas for art and a modest one for architecture — have seen more than 150 exhibitions presented by scores of Southland cultural institutions, large and small.

These shows narrate our shared history through paintings, sculptures and other diverse works of art. Many have been indispensable. Bookshelves are filled with significant publications, some of them now standard reference books, extending the program’s reach in time and space.

We haven’t quite finished with the current installment, PST: LA/LA. The series is focused on Latin American and Latino art. That’s fitting, given the ethnic plurality of the city’s population and the distressing degree to which the subjects have been overlooked. Some shows continue into the winter, while in January more than 200 artists will stage more than 75 performance works around Los Angeles as part of a collaborative festival organized by REDCAT.

Surely it is a sign of PST’s ongoing success that already some are wondering: What’s next? Will there be a fourth edition? What should its focus be?

Since PST is now tightly bound up with the Getty’s institutional brand, I inquired to find out the prospects.

“We have certainly discussed the possibility of a next Pacific Standard Time,” Getty Trust President Jim Cuno replied by email. “But while we can’t imagine not doing it again, it’s too early to confirm anything.”

I’ll take that as a “Probably.”

The first PST grew out of an effort to save the historical record of Los Angeles’ postwar art scene, spanning the years 1945 to 1980. (It was astonishing how little of real substance had been institutionally exhibited or published about such a transformative era.) Next came a loose, somewhat vague cluster of 11 shows on Modern architecture in the city.

Now, the enlightening, sometimes startlingly original PST: LA/LA is finishing up. To follow it, a theme as pressing as the first two art-focused series is crucial.

My vote: Pacific Standard Time should underwrite full retrospective exhibitions of artists with significant histories of working in Los Angeles, beginning in the late 19th century and continuing to the present.

Not project shows. Not young or emerging or new artist surveys. Not a phalanx of partial looks at a segment of an established artist’s output.

Instead, I mean full, rigorous accountings of historical figures, as well as artists beyond mid-career who have been in it for the long haul — a generation or more. Womb-to-tomb considerations of individual artists and the lifelong arc of their art, together with in-depth analyses of living artists who have been working for at least 25 or 30 years.

Call it PST: Solo LA.

The thought came to me a year ago, before PST: LA/LA launched but well after it was in the works. (Museum shows typically take a few years — or more — to produce.) The inspiration was the moving, breathtakingly beautiful John McLaughlin retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

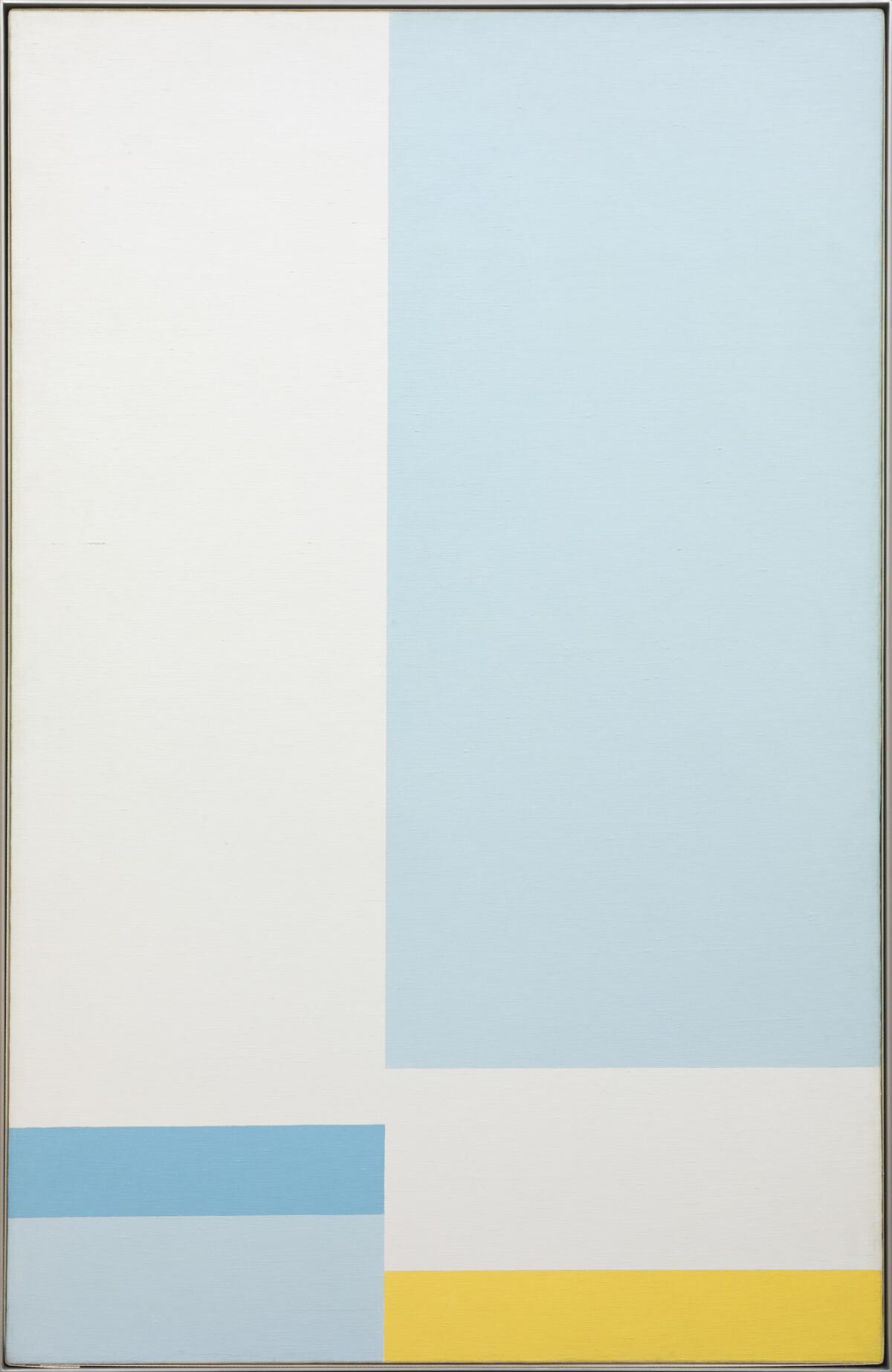

It’s a show I had waited years, even decades to see. McLaughlin, born in 1898 and a self-taught painter who didn’t begin making art until he was nearly 50, is the first artist of international stature to emerge in Los Angeles after World War II. (McLaughlin died in 1976.) The Laguna Art Museum had done a marvelous survey in 1996, breaking ground, but a full-dress retrospective with a major book about the painter’s radically inventive, quietly influential geometric abstractions had eluded him during his life.

And continued to for the next 40 years.

The reason is not mysterious. The profile of the art market significantly shapes the selection of museum retrospective subjects. McLaughlin’s market had always been modest at best.

Independent museum resources are certainly essential to bring a solo retrospective to fruition; but an artist’s position in the market, whether primary or resale, has an impact on the nexus of collectors, galleries, auction houses and even foundations and collegial museums available to help make a retrospective feasible.

A full-scale museum study costs money to research, organize and assemble, and exhibition catalogs are not inexpensive to produce. Signing up other museums to circulate a show and defray costs depends in part on the likelihood of funding, since shipping, insurance and installation can be expensive.

Market viability is not the sole determining factor, but it is a major hurdle. Check the dozen or so full-scale retrospective exhibitions, especially of contemporary artists, shown at LACMA and the Museum of Contemporary Art over the last five years; with rare exception, they relied on significant funding help from a relatively small number of powerhouse art galleries or a prominent auction house.

The problem is not that artists with a sturdy market don’t merit the attention, only that the much greater number of meritorious artists can expect to get passed by if they are without substantial commercial affiliation and support. (The same is true of artists’ estates, as was the case with McLaughlin.) The problem, in other words, is not with what is shown and documented but with what isn’t.

To cite one obvious example: The Art Newspaper recently reported that women average about 27% of major solo exhibitions. The art market is characterized by exclusionary limitations — white male artists are most favored — which never reflects the lived experience and complex infrastructure of a region’s artistic history.

Compounding the dilemma: Almost all artists working in Southern California have, until recently, operated apart from a robust market. For museum programs, history gets distorted. The city’s art life is poorer for it, the audience badly served.

I’ve made a point of not listing potential exhibition candidates from the last 125 years. First, such a list is far too long, and a primary purpose of PST: Solo LA would be to diminish the number of overlooked artists, not repeat the predicament. And second, I’m very curious to see what the region’s savvy curatorial talent would come up with; I’d hope for surprises.

Retrospectives are not easy to organize. In terms of needed gallery space or staffing, some venues that have participated in past PST programs might not have the wherewithal to manage the demands of a full-scale accounting of an artist’s entire career. Accommodations would need to be made. That’s doable in the planning.

The Getty Foundation wouldn't foot the entire bill, either. As with previous Pacific Standard Time installments, each institution would be expected to seek other funding to round out their budgets.

Yet, what makes a retrospective theme pressing is the art market behemoth that dominates so much of our cultural life today, casting dark shadows. Perhaps alone among cultural institutions, the Getty has the capacity to offer a significant counterbalance. We’d all be richer for it.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

'Golden Kingdoms' exhibition filled with spectacular finds

An artist’s proposal to turn the Korean DMZ into a bridge of peace

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.