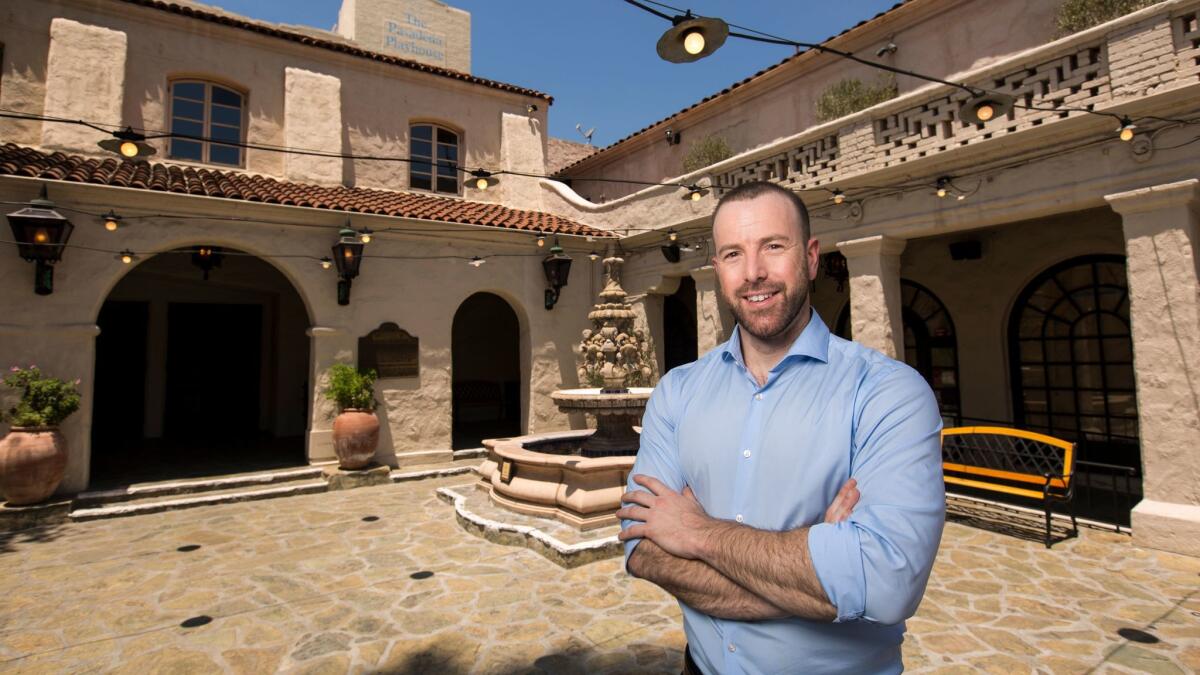

Can this man save the Pasadena Playhouse?

- Share via

Danny Feldman pauses for a moment, soaking in the view while taking his beagle Hunter for his morning walk along El Molino Avenue in Pasadena. “Look at all the people — young people, couples, families — so much energy,” he says. “I’m so excited. There’s a Trejo’s Cantina going in here. Margaritas and guacamole before theater! And after theater too!”

Feldman isn’t the president of Pasadena’s Chamber of Commerce, but he may well be the community’s biggest booster. The new leader of the Pasadena Playhouse has returned to his native Southern California after a seven-year stint in New York and he couldn’t be happier.

“This was a theater I came to as a kid,” he says. “I believe this is one of the most beautiful theaters in the world.”

The Pasadena Playhouse, which holds the designation of the State Theater of California, marks its centennial this summer. And while that’s reason to celebrate, the theater continues to struggle for survival amid serious financial challenges. Now, eight months into the job, Feldman has his work cut out for him.

Back at the office, Hunter settles into his dog bed under Feldman’s tidy desk, which is covered with assorted papers, two editions of the play “Our Town,” a book about the history of the Pasadena Playhouse and an orchid that looks like it would benefit from a little water. Behind what Feldman calls “the world’s most uncomfortable sofa” are striking posters of upcoming shows, minimalist in design but bursting with color. On the opposite wall are four small panels that display the evolution of the new Playhouse logo, which, like the posters, were custom created by Paula Scher of the famed design firm Pentagram as part of the theater’s recent rebrand.

Feldman has been camped out in a temporary office at the Playhouse since he arrived in October, transitioning into the role of producing artistic director as Sheldon Epps ends his 20-year tenure. Feldman’s position is new, combining the artistic job with the business-side role of executive director. As he settles into a chair to talk about his vision and his first season, Feldman can barely contain his excitement.

“To me, the season was really tied to the 100th anniversary of the Playhouse. It’s a defining moment in the theater’s history. Where I draw most of my inspiration is bridging the past and future,” he says, running down the list with the enthusiasm of a kid on show-and-tell day at school.

His inaugural season consists of “Our Town,” a co-production with Deaf West Theatre; an immersive production “Pirates of Penzance”; the Southern California premiere of Mike Bartlett’s play “King Charles III”; an updated version of Culture Clash’s 1998 play “Bordertown”; and one yet-to-be-announced show. (More details below.)

“We’re looking to build a robust audience that has a diversity of tastes — one that is a little adventurous but also wants to have great theatrical experiences,” Feldman says. “I think all of these shows provide that. It’s a refreshing look at classics.”

Theater, Feldman will tell you, is in his DNA.

“I love still to this day sitting in the theater with the lights going down and the feeling that this might be the best thing I’m ever about to see,” he says.

Though his parents weren’t involved with the arts, they instilled a passion for theater. The walls of his bedroom in West Hills were lined with posters of shows he saw with his family. “My very first one was ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. It shaped me,” says Feldman, 37. “The second show was ‘Phantom of the Opera’ at the Ahmanson. I saw that so many times. I wanted to be like Hal Prince.”

Feldman went on to study music at UCLA, where he served as music director in a number of student productions, including “Once Upon a Mattress,” staged by Bruin alum Carol Burnett.

“I wanted to be a music director, but my theater professor in the music department basically said to me, ‘You’re too bossy,’ because I would sit in the pit and look up and be like …” Feldman scrunches his face and rolls his eyes. “He said, ‘You should be a producer.’”

So the sophomore dipped his toes into professional theater, producing the pop opera “bare” at the Hudson Theatre in Hollywood. The musical became a cult hit. He went on to form a production company that would produce the L.A. premiere of “Corpus Christi,” Terrence McNally’s gay Passion play, and other shows in small theaters.

Upon graduation, he took a job with the now-defunct Reprise theater company, working his way up to general manager. “I loved that job. I loved doing classical musicals,” Feldman says.

But New York beckoned. After eight years with Reprise, Feldman cold-applied to the Labyrinth Theater Company in New York, whose roster has included Ethan Hawke, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Lynn Nottage and the late

“It was love at first interview,” says outgoing Labyrinth artistic director Mimi O’Donnell. “We were a team. It felt like he was my partner.”

Feldman immediately immersed himself in all aspects of the small theater company, getting to know the playwrights and artists and learning all he could about play development.

“Artists love him. They could talk to him,” O’Donnell says. “He wasn’t just the executive director who just dealt with numbers; they could have a conversation with him.”

The feeling was mutual. So when the Playhouse approached him during its search for a new leader, Feldman wasn’t looking to leave. “I kept verbally saying that I wasn’t interested in this, but I couldn’t stop thinking about it,” he says. “I started seeing the opportunity that was here. It was a great challenge, but an even greater opportunity.”

The challenge Feldman faces is familiar to nonprofit theaters across the country: building new audiences at a time when donations and grants are scarce. But Pasadena Playhouse’s struggle has been particularly high profile, its deep roots making it not only the beneficiary of community good will but also the subject of swirling rumor.

In 2010, the Playhouse was on the brink of closure, laying off nearly all its staff, canceling the remainder of its season and eventually filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection (its third since its founding in 1917). About three months later, it emerged from bankruptcy, thanks in large part to a $1-million matching gift from Mike Stoller, half of the songwriting team Leiber & Stoller, and his wife, Corky Hale Stoller.

Nearly a decade later, things remain shaky, according to sources with knowledge of finances at the Playhouse, whose 2016-17 budget is more than $7 million. As recently as last year, board members had to provide loans to help with cash flow, sources say. In January, the theater was sent scrambling when Gov. Jerry Brown pulled from his budget $1 million in funds earmarked for renovations, including a new lobby. The funds were restored in May, but not before the theater rushed to secure loans from donors.

Late last year, two previously announced large-cast productions from Epps’ final season, David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” and Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night,” were pulled from the schedule and replaced with the three-hander “The Originalist,” about the late Supreme Court Justice

“Cost was a factor, just like it is a factor in every show. But I think it is incorrect to say it was all financial or it was a change in artistic directors,” Feldman says. “It was a variety of reasons. We saw a real opportunity to do two plays about what is going on in America right now. It just felt right to do.”

In the months after Feldman’s arrival, the Playhouse faced a firestorm of criticism when it presented “God Looked Away,” starring Al Pacino and Judith Light. Dotson Rader’s play was billed as the first of the Playhouse’s PlayWorks Development productions, meaning it was still in a work in progress. But with top ticket prices of $250 and some patrons unaware they were paying for an unfinished play, complaints rolled in. Times critic Charles McNulty called the production “exploitative drivel,” and questions arose whether “God Looked Away” was a last-gasp effort to raise money.

“The decision to do that show was not financially motivated,” Feldman says. “The decision to do that show was about establishing a program here to develop new work as this theater has been doing for 100 years.”

The PlayWorks program, he says, is part of his broader mission to educate the community and to eventually bring theater training back to the Playhouse, whose alumni include Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman. Sure, there was criticism, he says, “but there were also people who felt very happy with their experience and would have paid more for that experience. Is ‘Hamilton’ worth $1,000 or whatever? There are people who pay that and have no regrets.”

The theater offered $25 and $60 tickets in the orchestra section at every performance, he says. “We are trying to break through the idea that for younger people or people with lower income, the theater is not for them,” he says. “My job is to make sure we are accessible to a wide swath of people.”

Finally, he says, “The Playhouse is in the black. This season has a surplus budget. It’s certainly true our development production of ‘God Looked Away’ gave us a boost. But it did not save this organization; that is not what’s paying for next season. That is certainly not the case.” He notes that he has secured financial support for at least two productions in the upcoming season.

Board Chairman Brad King has confidence that Feldman can turn things around.

“While we had been struggling financially and Danny came into a very difficult financial situation, we worked incredibly hard at resetting the position — hitting the reset button,” he says. “We have brought in new donors from the community because they see Danny and what he is doing.”

Feldman isn’t daunted by the challenges, referring to himself as “bizarre” in that he loves fundraising.

“The way I look at it is I inherited what I inherited,” he says. “I came in Day 1 and said, ‘Here’s my situation and now let’s build.’”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Feldman has launched post-show talkbacks — not with the casts, but with people billed as experts to the topics in the productions. He started rebranding the theater, a process that includes its logo and website. He is exploring ties to L.A.’s 99-seat theaters.

“Pasadena Playhouse has always been bold in trying new things. It’s in our DNA — and my DNA — to explore and be curious and push,” he says. “I’m personally driven by finding new ways of doing things.”

To that end, Feldman introduced a new subscription model, similar to museum memberships. Instead of buying a season subscription, patrons will become yearlong “members” with priority access to tickets, choice in when they attend shows and invitations to special events and talks.

“We are in a self-curating society,” he says. “The metaphor I use is iTunes and the idea that once people were able to buy the song versus the album, that was really a big change. People are interested in flexibility.”

Feldman is the second youngest artistic director in the Playhouse’s 100 years, and certainly among the younger leaders of nonprofit theaters of its size nationwide. And though his work has been on the financial side, rather than the creative, most who know him don’t seem concerned.

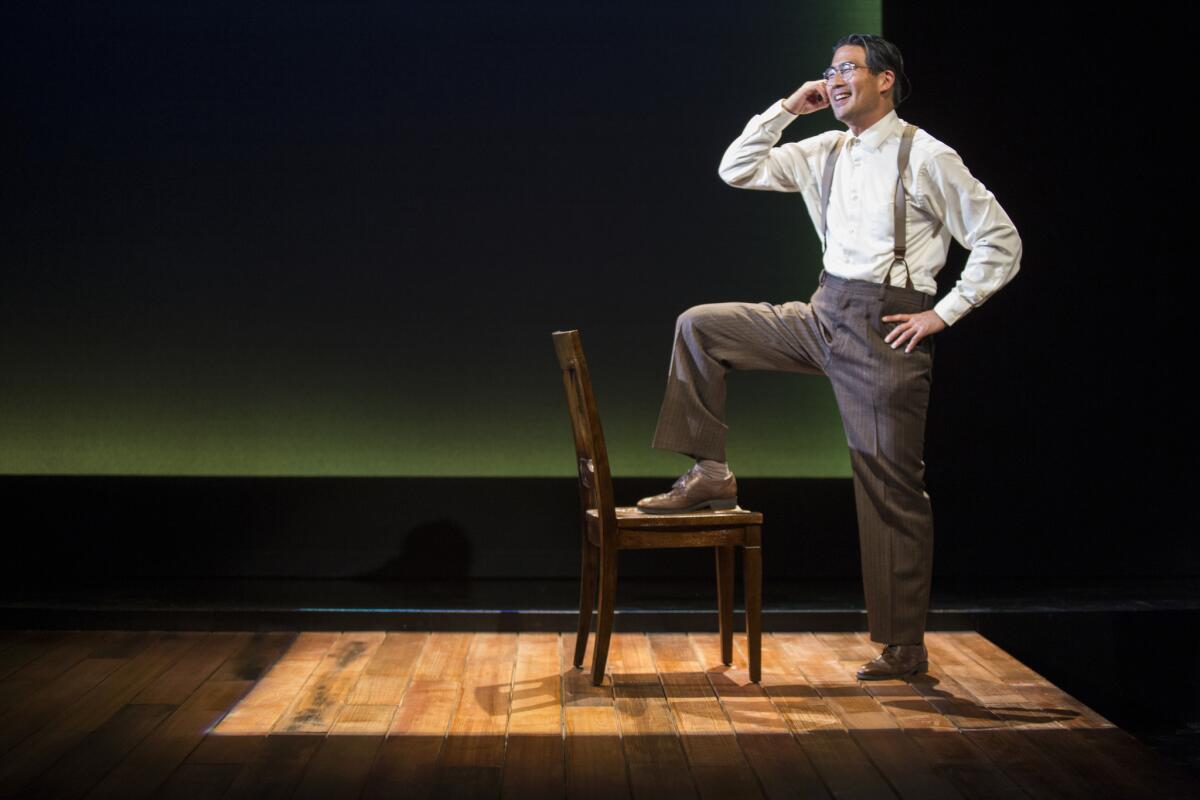

Jessica Kubzansky, director of “Hold These Truths,” says Feldman was present but not intrusive during rehearsals, regularly checking in to make sure she had what she needed.

“He is passionately interested in the details. It’s exciting to have an artistic director who cares as much as you do. That’s not always the case,” says Kubzansky, a veteran Playhouse director and co-artistic director of Theatre @ Boston Court in Pasadena.

During its leader search, the board asked candidates to assemble a potential season.

“That was just an incredible way for them to describe and clarify where they were coming from, from the creative side,” King says. “Danny really shined. He had such passion and was able to put together a really exciting kind of vision for where he would go.”

O’Donnell acknowledges there will be a learning curve for Feldman, “just as there is in any new job or new adventure you take on. But he’s a guy who asks a lot of questions. His ability to not be OK with something mediocre is astounding. He will push himself and the people around him until it’s the best that it can be,” she says.

“As long as his board and the community of Pasadena and the L.A. theater community embrace him, I’m telling you, there’s nothing that is going to stop that guy,” O’Donnell says. “He’s going to turn that organization around. He’s not going to sleep until he does.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Pasadena Playhouse’s 2017-2018 season

Danny Feldman chose his first season at the Pasadena Playhouse — the 100th year of the theater — with a nod to the past but with eyes focused on the future. Here he talks about his choices:

‘Our Town’ (Sept. 26-Oct. 22)

“It’s my absolute favorite play, which is why it’s my first production. It’s one of the most classic American plays there is. What many people don’t realize is that when it came out in 1938, it was revolutionary. I discovered in my process of picking this play that it opened at the McCarter Theater in, I think, 1938, and was done here on our stage in 1939. I have the pictures to prove it. We’re doing it with Deaf West Theatre, so that will be a totally different take on it.”

‘King Charles III’ (Nov. 7-Dec. 3)

“Besides being the thing that everybody loves — the sort of tabloid-y nature of the royal family and what’s going on in their heads — the play has a major theme about what happens when our institutions start cracking. Between Brexit and conversations happening in America today, it’s fascinating to look at our lives and what’s going on, removed, through the British experience in a future-history play. What pushed me over the edge on that play was I wanted to do some sort of tribute to Shakespeare in the season.”

‘Pirates of Penzance’ (Jan. 23-Feb. 18)

“‘Pirates of Penzance’ is the music of ‘Pirates of Penzance’ — it’s operetta. But it’s operetta played with guitars and banjos and in a fun way, with the Hypocrites theater company. I’ve read so many books that say ‘Oklahoma!’ is the birth of the American musical. ‘Pirates of Penzance’ happened in the late 1900s, and I know it was British, but it appeared in America. You see a straight line in operetta in to Jerome Kern and Rodgers & Hammerstein. That show is about taking something that feels old and staid and dusty and bringing amazing new life to it in a very contemporary way. That’s a great sort of metaphor for the Pasadena Playhouse.

(One to-be-announced production)

‘Bordertown Now’ (May 29-June 24)

“Culture Clash wrote that play 20 years ago. It was like June 2, 1998, that it opened and we open June 3, 20 years later. We are re-commissioning the play, and they’re going back to the border to see what is going on now. We’re not just doing the ‘Bordertown’ that everyone saw 20 years ago. Some of the material will be the same, because some of it is still relevant, but they’re also going to look at what a ‘border town’ is today in the world we live in now. It gives us an opportunity to have a play of the moment.”

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

MORE THEATER COVERAGE:

What would a critic write to the creator of 'Letters From a Nut'? Let's start with …

'This Is Us' writer Bekah Brunstetter ices a big year with a timely ‘Cake’

Allen Leech and Ginnifer Goodwin on the mind-bend that is 'Constellations'

Shakespeare and the politics of our age: Trump, 'Julius Caesar' and now 'Richard II'

Diary of a world premiere: Join Rajiv Joseph as the curtain rises on his 'Archduke'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.